A New Kind of Visual News

See a visual discussion of the findings.

[1]

In the seven days following the disaster (March 11-18), the 20 most viewed news-related videos on YouTube all focused on the tragedy-and were viewed more than 96 million times.

What people saw in these videos also represented a new kind of visual journalism. Most of that footage was recorded by citizen eyewitnesses who found themselves caught in the tragedy. Some of that video was posted by the citizens themselves. Most of this citizen-footage, however, was posted by news organizations incorporating user-generated content into their news offerings. The most watched video of all was shot by what appeared to be fixed closed-circuit surveillance camera at the Sendai airport.

The disaster in Japan was hardly a unique case. Worldwide YouTube is becoming a major platform for viewing news. In 2011 and early 2012, the most searched term of the month on YouTube was a news related event five out of 15 months, according to the company’s internal data.

What is the nature of news on YouTube? What types of events “go viral” and attract the most viewers? How does this agenda differ from that of the traditional news media? Do the most popular videos on YouTube tend to be videos produced by professional news organizations, by citizens or by political interest groups or governments? How long does people’s attention seem to last?

[2]

The data reveal that a complex, symbiotic relationship has developed between citizens and news organizations on YouTube, a relationship that comes close to the continuous journalistic “dialogue” many observers predicted would become the new journalism online. Citizens are creating their own videos about news and posting them. They are also actively sharing news videos produced by journalism professionals. And news organizations are taking advantage of citizen content and incorporating it into their journalism. Consumers, in turn, seem to be embracing the interplay in what they watch and share, creating a new kind of television news.

At the same time, clear ethical standards have not developed on how to attribute the video content moving through the synergistic sharing loop. Even though YouTube offers guidelines on how to attribute content, it’s clear that not everyone follows them, and certain scenarios fall outside those covered by the guidelines. News organizations sometimes post content that was apparently captured by citizen eyewitnesses without any clear attribution as to the original producer. Citizens are posting copyrighted material without permission. And the creator of some material cannot be identified. All this creates the potential for news to be manufactured, or even falsified, without giving audiences much ability to know who produced it or how to verify it.

Among the key findings of this study:

- The most popular news videos tended to depict natural disasters or political upheaval-usually featuring intense visuals. With a majority of YouTube traffic (70%) outside the U.S., the three most popular storylines worldwide over the 15-month period were non-U.S. events. The Japanese earthquake and tsunami was No. 1 (and accounted for 5% of all the 260 videos), followed by elections in Russia (5%) and unrest in the Middle East (4%).

- News events are inherently more ephemeral than other kinds of information, but at any given moment news can outpace even the biggest entertainment videos. In 2011, news events were the most searched term on YouTube four months out of 12, according to YouTube’s internal data: the Japanese Earthquake, the killing of Osama bin Laden, a fatal motorcycle accident, and news of a homeless man who spoke with what those producing the video called a “god-given gift of voice.” Yet over time certain entertainment videos can have a cumulative appeal that will give them higher viewership.

- Citizens play a substantial role in supplying and producing footage. More than a third of the most watched videos (39%) were clearly identified as coming from citizens. Another 51% bore the logo of a news organization, though some of that footage, too, appeared to have been originally shot by users rather than journalists. (5% came from corporate and political groups, and the origin of another 5% was not identified.)

- Citizens are also responsible for posting a good deal of the videos originally produced by news outlets. Fully 39% of the news pieces originally produced by a news organization were posted by users. (The rest of the most popular news videos of the last 15 months, 61%, were posted by the same news organizations that produced the reports.) As with other social media, this has multiple implications for news outlets. Audiences on YouTube are reshaping the news agenda, but they are also offering more exposure to the content of traditional news outlets.

- The most popular news videos are a mix of edited and raw footage. Some pundits of the digital revolution predicted that the public, free to choose, would prefer to see video that was unmediated by the press. The most viewed news videos on YouTube, however, come in various forms. More than half of the most-viewed videos, 58%, involved footage that had been edited, but a sizable percentage, 42%, was raw footage. This mix of raw and edited video, moreover, held true across content coming from news organizations and that produced by citizens. Of videos produced by news organizations, 65% were edited, but so were 39% of what came from citizens.

- Personalities are not a main driver of the top news videos. No one individual was featured in even 5% of the most popular videos studied here-and fully 65% did not feature any individual at all. Within the small segment of popular videos that are focused on people, President Barack Obama was the most popular figure (featured in 4% of the top videos worldwide). These ranged from speeches posted in their entirety to satirical ads produced by his political opponents.

- Unlike in traditional TV news, the lengths of the most popular news videos on YouTube vary greatly. The median length of the most popular news videos was 2 minutes and 1 second, which is longer than the median length of a story package on local TV news (41 seconds) but shorter than the median length on national network evening newscasts (2 minutes and 23 seconds). But the variation in the length of the YouTube videos stands out even more. While traditional news tends to follow strict formulas for length, the most popular news videos on YouTube were fairly evenly distributed-from under a minute (29%), one to two minutes (21%), two to five minutes (33%) and longer than five (18%).[4]

The news viewership on YouTube is probably still outpaced by the audience for news on conventional television worldwide. While those top 20 tsunami videos were viewed 96 million times worldwide the week of the disaster, for instance, more people almost certainly watched on local and national television around the globe. Twenty-two million people on average watch the evening news on the three broadcast channels each night in the United States alone, and larger numbers watch local TV newscasts.

But YouTube is a place where consumers can determine the news agenda for themselves and watch the videos at their own convenience-a form of “on demand” video news. In the case of the Japanese earthquake and tsunami, audience interest continued for weeks. The disaster remained among the top-viewed news subjects for three straight weeks. Based on the most viewed videos each week listed by YouTube, it was also the biggest news story on the site for 2011.

[5]

Seven years after it was developed by three former employees of PayPal, the reach of YouTube is enormous. The video sharing site is now the third most visited destination online, behind only Google (which owns YouTube) and Facebook, based on data compiled by Netcraft, a British research service. According to the company’s own statistics, more than 72 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute. The site gets over 4 billion video views a day. Slightly under a third of those, 30%, come from the United States.

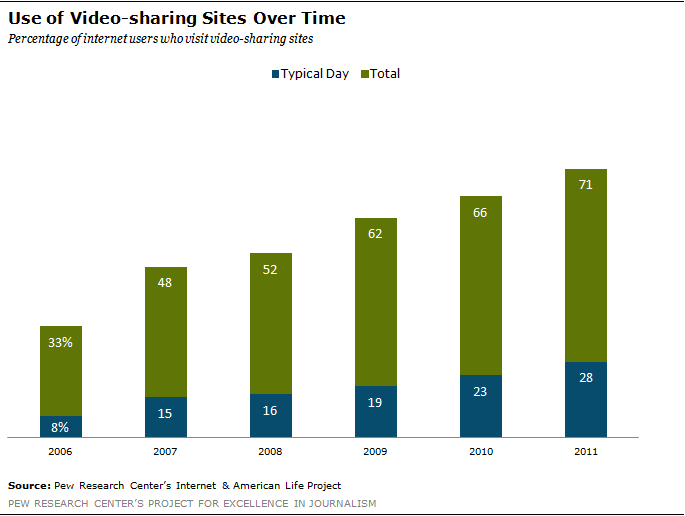

YouTube has also become a part of the lives of most Americans. Fully 71% of adults have used sites like YouTube or Vimeo at some time, according to a 2011 survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. That is up from 66% in 2010. And 28% visit them daily.

Bought by Google in 2006 for $1.65 billion in stock, YouTube has moved from being a repository of videos to becoming a force that is investing in content creation (if not doing the creation themselves). In 2007, the company created a Partner Program, which shares revenues with content creators in order to encourage the production of more creative content. That program now has more than 1 million partners in 27 countries, including news organizations such as CBS, the BBC and National Geographic. In addition, the company has given direct grants to a smaller group of news content producers as a further way of promoting new ideas and production models.

So far, the approach from news organizations has been a blend of participation and resistance. Many news outlets have developed their own YouTube channels and are avidly posting content. The Associated Press, for example, created its channel in 2006 and now boasts more than 250,000 followers and more than a billion views of its videos. (A user becomes a follower of a YouTube channel by hitting the ‘subscribe’ button, which places updates from that channel on the user’s homepage.) The New York Times’ news channel has more than 78,000 followers while Russia Today has more than 280,000. Some news services, such as ABC News, put on YouTube many of the same stories that appear on their television channel.

[6]

Some content producers have combined both approaches, posting their own content but also blocking it from being viewed in certain countries. They may choose to do this for copyright preferences or to prevent certain content from being viewed in countries that might consider it culturally insensitive.

Some non-news organizations, including governments, have also attempted to restrict the availability of their content on YouTube, mostly for political reasons. In March 2009, for example, the government of Bangladesh blocked access to the site entirely after a recording of a private meeting between the Prime Minister and army officers was uploaded. The incident occurred two days after an attempted mutiny by border guards left more than 70 people dead. Government officials insisted it was in the country’s “national interest” to block the site and more videos might worsen the tense situation. China, Libya, Pakistan and Iran have also all attempted at one point or another to block YouTube content.

The evolving government and media policies toward YouTube make understanding the nature of what news content is on the site and which is most popular all the more important.

Footnotes

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]