There are wide gaps between men and women working in science, technology, engineering and math jobs when it comes to perceptions of fair treatment for women at work and experiences of workplace discrimination.

Women in STEM jobs are much more likely than men in such jobs to say they have experienced discrimination at work because of their gender and to consider discrimination a major reason that more women are not working in STEM. While the majority of STEM workers say their gender has made no particular difference in their success, women in STEM jobs are more inclined than men to say their gender has made it harder for them to succeed at work. Those that feel this way raise a number of concerns including pay gaps and unequal treatment from their coworkers stemming from gender stereotypes.

Experiences with workplace discrimination and concerns about gender inequities are more pronounced among women working in computer positions; among those working in workplaces where men outnumber women; and among women with advanced degrees, more of whom presumably work in higher level, professional positions compared with other women in STEM jobs.

Although a higher share of women in STEM jobs say they have experienced at least one form of discrimination at work because of their gender, similar shares of women in STEM jobs and non-STEM jobs say they have personally experienced sexual harassment. Women in STEM jobs also tend to share similar perspectives with working women in non-STEM jobs when it comes to the value of gender diversity and the amount of attention paid to gender diversity at work.

Most Americans value gender diversity at work; more than four-in-ten say diversity contributes to organizational success

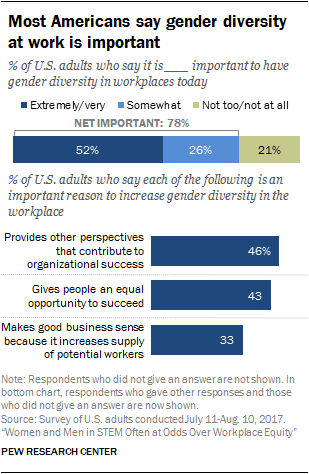

Americans are largely supportive of gender diversity in the workplace, with about half of U.S. adults (52%) characterizing it is as “extremely” or “very” important and 26% saying it is “somewhat” important.

When asked to cite reasons for increasing gender diversity in the workplace, 46% of Americans say an important consideration is that gender diversity provides other perspectives that contribute to the overall success of companies and organizations. A similar share, 43%, cite giving people an equal opportunity to succeed as an important reason, while one-third (33%) say gender diversity makes good business sense because it increases the supply of potential workers.

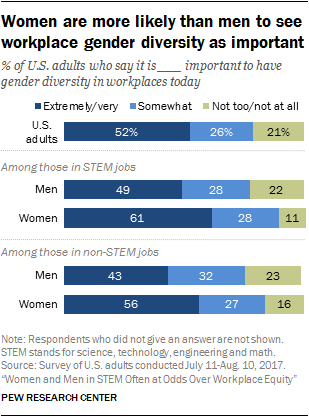

Americans’ level of support for gender diversity depends, in part, on their own gender. Whereas more than half of women in STEM jobs and non-STEM jobs alike believe that such diversity is highly important (61% and 56%, respectively), fewer men in STEM and non-STEM jobs say the same (49% and 43%, respectively).

Support for gender diversity also depends, in part, on levels of education. Those who hold advanced degrees, whether they work in STEM or non-STEM jobs, express more support for the importance of gender diversity, on average.

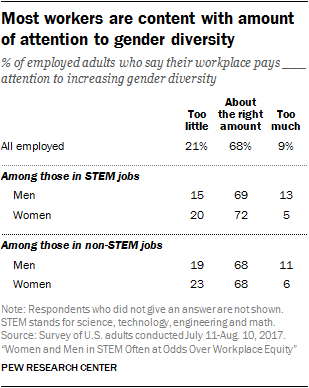

Around seven-in-ten (68%) employed adults believe their workplaces are giving sufficient attention to increasing gender diversity. Similar shares of women and men, in both STEM and non-STEM jobs, share that assessment.

But two-in-ten women in STEM jobs (20%) and 15% of men in such jobs say there is too little attention to diversity where they work.

Men in STEM jobs are about twice as likely to think there is too much attention given to gender diversity (13% vs. 5% of women in STEM jobs) in their workplace.

On this issue, workers in non-STEM positions look similar to those in STEM, with men more likely than women to say there is too much attention to gender diversity but majorities of both genders say attention is sufficient.

About half of women in STEM consider discrimination a major factor behind women’s limited representation in STEM occupations

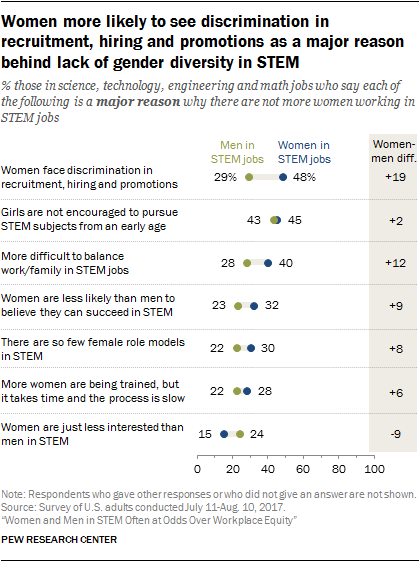

When asked to explain why there are not more women working in STEM jobs, a major reason, cited by around four-in-ten (44%) people in STEM jobs, is lack of encouragement for girls in these subjects from an early age. On this, men and women in STEM jobs tend to agree (43% of men and 45% of women in STEM jobs say this).

However, women in STEM jobs are far more likely than their male counterparts to cite discrimination in hiring and promotions as a major reason why there are not more women working in STEM (48% vs. 29%).

In addition, somewhat higher shares of female than male STEM workers cite the difficulty of balancing work and family in STEM jobs (40% vs. 28%), lack of belief among women that they can succeed (32% vs. 23%), the shortage of female role models in STEM (30% vs. 22%) and the slowness of the training “pipeline” (28% vs. 22%) as major reasons why there are not more women working in STEM fields.

The one reason listed by larger shares of men than women is interest: about a quarter of men in STEM jobs (24%) say that a major reason there are not more women working in these positions is that women are less interested than men in STEM. Just 15% of women with STEM jobs say the same.

Half of women working in STEM say they have experienced gender discrimination at work; about a fifth have personally encountered sexual harassment

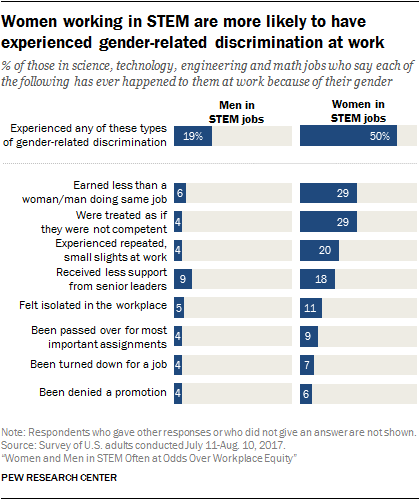

Half (50%) of women in STEM jobs say that they have experienced at least one of eight forms of gender-related discrimination in the workplace, more than women in non-STEM jobs (41%) and far more than men in STEM positions (19%).

The most common forms of gender discrimination reported by women in STEM jobs are earning less than a man doing the same job (29%), having someone treat them as if they are not competent because of their gender (29%), experiencing repeated, small slights in their workplace (20%), and receiving less support from senior leaders than a man who was doing the same job (18%).

Previous Pew Research Center surveys have found more women than men report experiencing gender discrimination. The share reporting these experiences tends to vary depending on whether or not the questions are focused on the workplace, per se, and whether they rely on a summary judgment of experienced discrimination or ask separately about specific types of discriminatory behaviors.

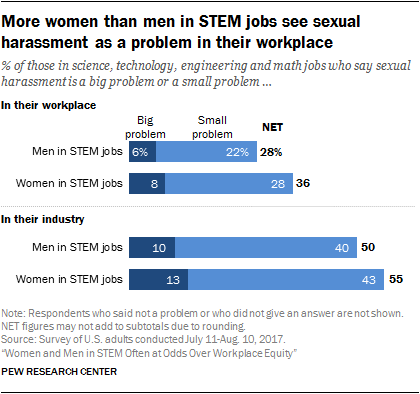

When it comes to the issue of sexual harassment in the workplace, workers are more likely to judge harassment as a problem in their industry than in their own workplace.

Among all those working in a STEM job, 53% consider sexual harassment at least a small problem in their industry sector, compared with 32% who say the same about their own workplace.

Women in STEM jobs are more likely than their male counterparts to say sexual harassment is at least a small problem in their workplace (36% vs. 28%) though similar shares say it is at least a small problem in their industry (55% vs. 50%). But, there are no gender differences among non-STEM workers about the degree to which sexual harassment is a problem. Some 36% each of men and women in non-STEM jobs consider sexual harassment to be at least a small problem where they work.

Overall, 53% of STEM workers say sexual harassment is at least a small problem in their industry sector, compared with 46% of non-STEM workers. About a third of STEM workers (32%) and 36% of non-STEM workers say sexual harassment is at least a small problem where they work.

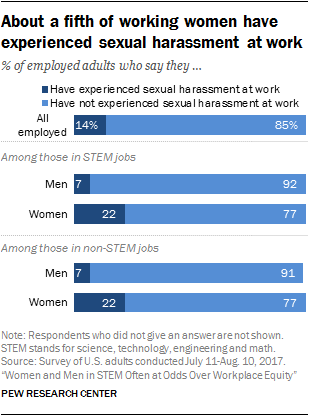

Women in STEM jobs are also about three times as likely as men in these jobs (22% vs. 7%) to say that they have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace. Similarly, working women in non-STEM occupations are more likely than their male counterparts to say they have experienced sexual harassment at work (22% and 7%, respectively).

Workers who have experienced sexual harassment at work – whether men or women – are more likely to say that sexual harassment is a big problem in their workplace (22% do vs. 8% of those who have not been sexually harassed at work) and in the industry where they work (28% vs. 9%).

These findings were gathered before the string of prominent sexual harassment allegations in Hollywood and beyond that sparked a public discussion of these issues, including the social-media-driven #MeToo movement.

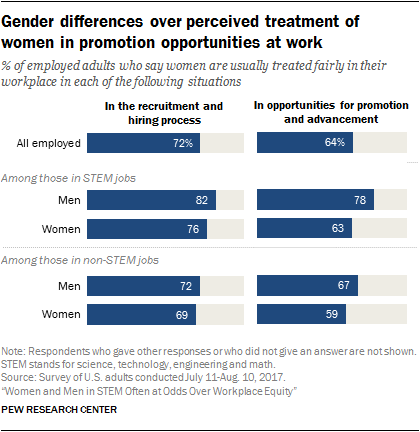

Perception of fair treatment for women in promotion opportunities differs by gender, and the gaps tend to be wider among those in STEM than non-STEM positions

Overall, most workers in the U.S. believe that women are “usually treated fairly” where they work when it comes to recruitment and hiring (72%) as well as in opportunities for promotions and advancement (64%). Smaller shares say women are sometimes treated fairly and sometimes treated unfairly when it comes to hiring (21%) or opportunities for advancement (27%), while fewer than one-in-ten say that women are usually treated unfairly where they work during either process.

Women in STEM positions are somewhat less likely than their male counterparts to consider women’s treatment when it comes to opportunities for advancement as usually fair. Some 63% of women in STEM jobs say women are usually treated fairly where they work when it comes to promotion and advancement opportunities, compared with 78% of men in STEM jobs. There is a similar, though less pronounced, gender gap in perceptions of fair treatment in opportunities for promotion and advancement among non-STEM workers.

One-in-five female STEM workers see their gender as a barrier to workplace success; this group raises a variety of concerns from inequalities in pay to evaluations of performance

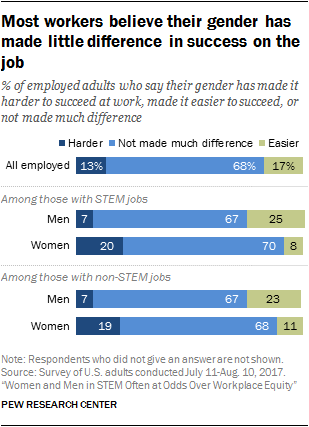

The majority of American workers say their gender has either made little difference (68%) or has made it easier to succeed in their job (17%), while 13% of workers say their gender has made it harder to succeed at work.

More women (20%) than men (7%) in STEM positions believe their gender has made it hard for them to succeed at work. Majorities of both groups say gender has made no particular difference in their workplace success. On the flip side, a quarter (25%) of men and 8% of women in these jobs believe their gender has made it easier to succeed.

In this regard, women in STEM share common ground with those in other occupations. Some 19% of women in non-STEM jobs say their gender has made it harder to succeed in their job, compared with 7% of men in non-STEM occupations.

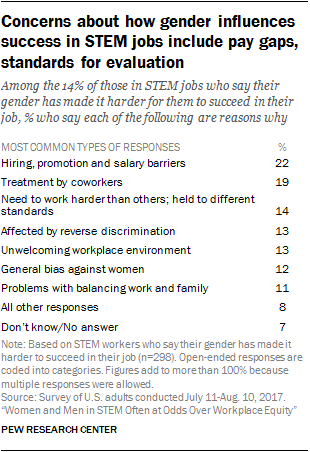

STEM workers who said that their gender has made it harder to succeed in their job were asked to explain why they said this. The most commonly cited hardship due to gender involved barriers to hiring and promotions and lower pay, including being turned down for leadership positions and being passed over for the best opportunities in the workplace (22% of this group).

Some examples of these concerns in their own words include:

“I make 75% of the salary of my male counterparts” – Multiracial woman, professor in allied health profession, 58

“There is a perception that men are better with technology and have the edge when it comes to promotions.” – White woman, systems analyst, 55

Some 19% of people who said their gender made it harder to succeed on the job gave examples of unfair treatment from coworkers. Examples of these concerns include:

“People automatically assume I am the secretary, or in a less technical role because I am female. This makes it difficult for me to build a technical network to get my work done. People will call on my male co-workers, but not call on me.” – White woman, technical consultant, 36

“I am more likely to be dismissed when I contribute. It took a lot longer for my efforts to be recognized than my male counterparts. More credence is given to male coworkers’ ideas who have not proven themselves yet.” – Black woman, software engineer, 36

Another 14% of those working in STEM who say their gender has made it harder to succeed at work describe needing to work harder than others to achieve the same success. Some examples:

“A woman has to be significantly better at her job to be judged just as good. The reality has not changed in 36 years even though there are more women in engineering now.” – White woman, engineer, 58

[to]

Another reason for difficulty with job success due to gender – cited by 13% of those who responded – referenced the general workplace environment, especially when women are underrepresented. For example:

[management]

“My workplace is run as a ‘boys club.’ It is harder for me to get my opinion heard over the males. The men can do no wrong.” – White woman, science teacher, 25

Among STEM workers who say that their gender has made it harder for them to succeed in their job, 13% say that they have been affected by reverse discrimination. Survey respondents in this group were exclusively men. Most in this group say that in they have been discriminated against in their workplaces in favor of hiring and promoting women:

“Today the white male is the enemy. I’ve seen too many qualified white males passed over for promotions or advancement in favor of a woman and/or minority. Qualifications don’t matter these days, rather your gender and race matter.” – White man, engineer, 47

“In the tech industry, with so many males in engineering roles, males are treated unfairly when applying to other roles. Women are treated unfairly because they are promoted and selected … with less experience and less qualifications so that management (and the company) can be seen as ‘diverse’ at the expense of someone who has objectively more experience and qualifications who happens to be male for middle management and higher.” – Asian man, software requirements engineering and management, 38

“Women have less competition for advancement and are given preference over equally qualified men in an attempt to get a politically correct gender diversity.” – Multiracial man, computer worker, 57

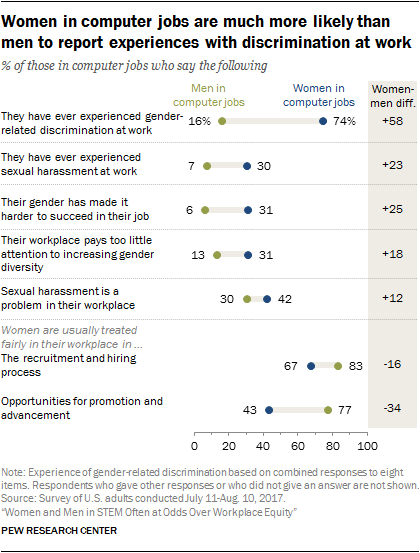

Wide gender gaps among computer workers and those working in majority-male workplaces over fair treatment at work

On average, women working in STEM jobs are more likely to report experiences with and concerns about gender inequities in the workplace compared with men in these jobs. Among women in STEM, those working in computer positions, those in workplaces where men outnumber women, and those with advanced degrees are particularly likely to have concerns about gender equity and to have experienced gender discrimination.

Roughly three-quarters (74%) of women in computer occupations say they have experienced gender discrimination at work, compared with 16% of men working in computer jobs. (Computer jobs include positions such as software development or data science, and include some who work in the technology industry and some who work in other sectors.)

Women in computer jobs are more likely than women in STEM, overall, to say they have experienced discrimination (74% vs. 50%) and these women are particularly likely to report pay inequities (46% vs. 29% of all women in STEM) and 40% say have been treated as if they were not competent at work because of their gender (29% of all women in STEM jobs say this).

Female computer workers are also more likely than male computer workers to say that their gender has made it harder to succeed in their job (31% vs. 6%), that they have personally experienced sexual harassment at work (30% vs. 7%), and that their workplace pays too little attention to increasing gender diversity (31% vs. 13%).

When it comes to judgments of workplace fairness for women, women working in computer occupations are less likely than men in computer jobs to say women are treated fairly in opportunities for promotion and advancement or in the recruitment and hiring process. While the majority of male computer workers (77%) say that women in their workplace are usually treated fairly in opportunities for promotion and advancement, fewer female computer workers (43%) say the same. Similarly, 83% of male computer workers say women in their workplace are usually treated fairly in recruitment and hiring, compared with 67% of female computer workers.

The same Pew Research Center survey asked about people’s perceptions of gender discrimination in the technology industry. There, too, women who work in computer jobs are more likely than men in these jobs to consider gender discrimination a major problem in the tech industry (43% to 31%); about twice as many men (32%) as women (15%) who work in these jobs say gender discrimination is not a problem in the industry.

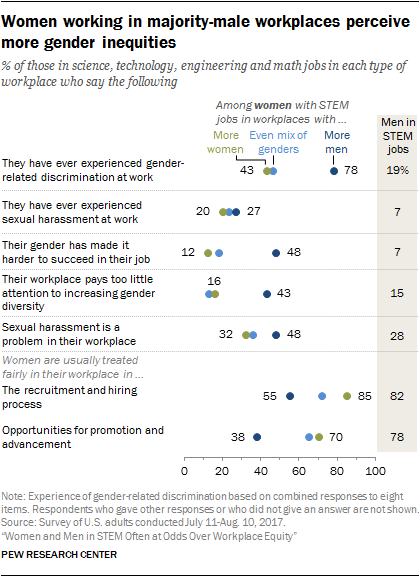

About half of women in STEM workplaces with a majority of men think their gender has made it harder to succeed in their job

The 19% of women in STEM jobs working in majority-male workplaces stand out in their views and experiences at work. These women are significantly more likely than women in majority-female workplaces or those in workplaces with an even mix of men and women to say they have experienced at least one of eight forms of gender-related discrimination at work (78% compared with 43% of those in majority-female workplaces) and to think their gender has made it harder to succeed in their job (48% vs. 12% of women in STEM jobs who work in majority-female workplaces).

A far greater share of STEM women in majority-male workplaces think there is too little attention to gender diversity at work (43% compared with 16% of women in majority-female workplaces). And, these women are more likely than those in majority-female organizations to consider sexual harassment a problem where they work (48% vs. 32%).

Further, women working in STEM jobs in mostly male workplaces are significantly less likely than women in majority-female workplaces or those with an even mix of men and women to say that woman are usually treated fairly in recruitment and hiring (55% say this, compared with 85% of women in workplaces with mostly women) or opportunities for promotion and advancement (38% vs. 70%).

By contrast, among men in STEM jobs, gender context is largely unrelated to views on gender equity in the workplace. One exception is that men working in STEM jobs with mostly women are more likely to say they have experienced any of eight types of gender-related discrimination at work (32% say this) than men in mostly male workplaces (15%) or workplaces with an even gender distribution (16%).

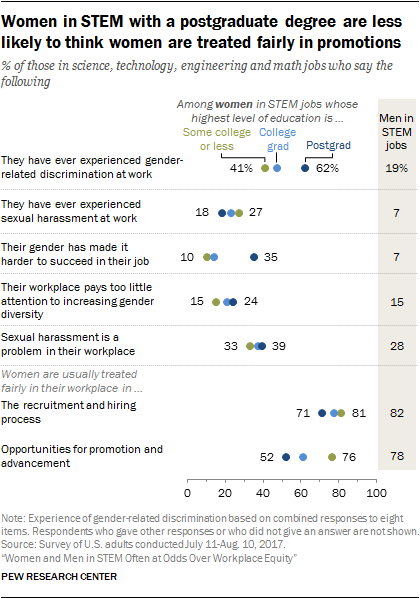

Women with advanced degrees in the STEM workforce are more likely to see inequities at work

There are also differences among women in STEM jobs by their level of education. Women with advanced degrees working in STEM jobs are more likely than other women in STEM jobs to report that they have experienced discrimination in their workplace because of their gender and to say that their gender has made it harder to succeed at work. And, women in STEM jobs who hold a postgraduate degree are less inclined to think women are usually treated fairly when it comes to opportunities for advancement where they work.

Similarly, highly educated women working in non-STEM jobs are more likely than women in such jobs with less education to report that they have experienced gender-related discrimination in the workplace either at a current or previous job.

By contrast, there are small or no differences among men in STEM jobs by education level across these measures. See Appendix for details.