It has long been clear in the research community that people’s willingness to discuss political issues depends on their access to news and on the social climate for discussion. This study explores people’s willingness to share their opinions on and offline about an important political issue. The report is built on Pew Research Center survey findings related to how people use social media, as well as traditional media, to get information on one political issue that dominated the news in the summer of 2013: the revelations by defense contractor Edward Snowden. In June 2013, Snowden leaked classified documents to The Washington Post and Britain’s Guardian newspaper about surveillance by the U.S. National Security Agency and some allied governments into the phone calling records and email exchanges of untold numbers of persons.6

Where people got news about the Snowden-NSA surveillance story

We asked people where they were getting information about the debates swirling around the Snowden revelations, and found that social media was not a common source of news for most Americans. Traditional broadcast news sources were by far the most common sources. In contrast, social media sources (Facebook and Twitter) were the least commonly identified sources for news on this issue.

- 58% of all adults got at least some information about this topic from TV or radio.

- 34% got at least some information from online sources other than social media.7

- 31% got at least some information from friends and family.

- 19% got at least some information from a print newspaper.

- 15% got at least some information while on Facebook.

- 3% got at least some information from Twitter.

Looking only at those Americans who use either Facebook or Twitter, 26% of Facebook users and 22% of Twitter users reported being exposed to at least some information about the government’s surveillance program on these platforms.

A relatively small number of Americans—12%—reported receiving no information about the debates over the government’s telephone and digital surveillance program. Some 15% of Americans said they relied on a single source of information about this issue. The majority relied on at least three information sources.

This reported use of Facebook and Twitter for news about the Snowden revelations is substantively lower than what has been reported previously for use of these platforms to access news more broadly. Data from the Pew Research Center’s 2013 report on “News Use across Social Media Platforms,” conducted over the same time period as our survey, found that 47% of Facebook users and 52% of Twitter users use these platforms to consume news. One explanation for the difference in our findings likely relates to the fact that in this survey we were asking about a single public issue, while the other Pew Research survey included broader types of news, including entertainment, sports, and politics.8

- Some might expect that internet users in general and social media users in particular are less likely to rely on traditional media sources for news on political issues because they have alternative sources. But, for internet users in general, and for most social media users, we find the opposite to be true. Using regression analysis to control for demographic characteristics, we find: Internet users are more likely than non-users to get news on the surveillance story from TV and radio. An internet user is 1.63 times more likely to have obtained even a little news on the Snowden-NSA revelations from radio and television than a non-internet user.

- Twitter users are more likely than non-Twitter users to get news on the surveillance story from TV and radio. A typical Twitter user (someone who uses the site a few times per day) is 2.25 times more likely to have obtained news on this issue through TV and radio than an internet user who does not use this platform, and 3.67 times more likely than a non-internet user.

- Instagram users were also more likely to get news on the surveillance story from traditional broadcast sources. A typical user of Instagram (someone who uses the site a few times per day) was 2.46 times more likely to have received television and radio news on this topic in comparison with an internet users who does not use Instagram, and 4.02 times more likely than a non-internet user.

This contrasts with the situation that applies to users of some other social media platforms:

- The typical Pinterest user (who uses the site a couple of times per week) is 0.92 times less likely to get news about the government’s surveillance program from TV and radio in comparison with an internet user who does not use this platform, but he or she is still 1.51 times more likely to get news from TV and radio than a non-internet user.

- Similarly, someone who uses LinkedIn a couple of times per week is 0.87 times less likely to get news on this issue from television and radio compared to an internet user who does not use LinkedIn, but still 1.41 times higher than for a non-internet user.

Facebook users are no more or less likely to obtain news through TV and radio than other internet users.

While some social media do seem to distract from traditional media sources, on the whole, these effects are relatively small. Someone who uses multiple social media sites at a typical level of use—Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and LinkedIn—is about 8 times more likely than non-internet users and 5 times more likely than internet users who do not use social media to get information about the government’s surveillance program through TV and radio (See Appendix, Table A).9 For the most part, social media users did not get their news through social media, they got it through television and radio.

Controlling for other factors, internet and social media use do not account for any of the difference in use of print newspapers to find information on the topic of the government’s surveillance program. Internet users, including those who use Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and LinkedIn, are as likely as anyone else to use newspapers for news about the government’s surveillance program.

Social media did not provide an alternative outlet for the 14% of Americans who were not willing to discuss the Snowden-NSA issue in person

While it has been suggested that social media might provide new channels for communication about important political issues, our survey suggests that few people are willing to deliberate online who would not also do so in person. Almost everyone in our sample who reported that they would be willing to discuss something on Twitter or Facebook also indicated that they would be willing to have a conversation on this topic in an offline setting. Only 0.3% of Americans reported that they were not willing to have a conversation about the government surveillance program when people were physically present, but were willing to have such a conversation through social media.

People’s overall willingness to share their views

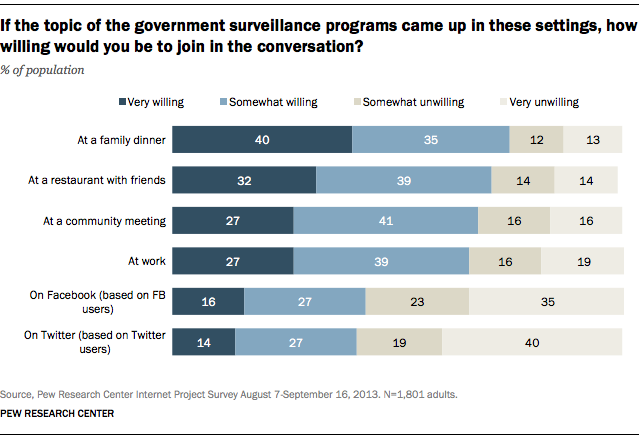

There are many social situations where people might have the opportunity to discuss political issues. We asked respondents to tell us how willing they would be to join a conversation “if the topic of the government’s surveillance programs came up” in a variety of settings, online and offline. We asked them how willing they would be to join in the conversation at a community meeting, at work, at a restaurant with friends, at a family dinner, on Facebook, and on Twitter.

In most social settings, the majority of Americans reported that they would be willing to join a conversation about the Snowden-NSA revelations. The only settings where most people were not willing to discuss their opinion was on Facebook and Twitter.

- 74% of all adults said they would be “very” or “somewhat” willing to join the conversation if the Snowden-NSA story came up at a family dinner.

- 74% of all adults said they would be “very” or “somewhat” willing to join the conversation if the Snowden-NSA story came up at a restaurant with friends.

- 66% of all adults said they would be “very” or “somewhat” willing to join the conversation if the Snowden-NSA story came up at a community meeting.

- 65% of employed adults said they would be “very” or “somewhat” willing to join the conversation if the Snowden-NSA story came up at work.

- 42% of Facebook users said they would be “very” or “somewhat” willing to join the conversation on Facebook.10

- 41% of Twitter users said they would be “very” or “somewhat” willing to join the conversation if the Snowden-NSA story came up on Twitter.

In all, 86% of Americans were willing to have a conversation in the physical presence of others—that is, at a public meeting, at a family dinner, at a restaurant with friends, or at work on the topic of the government’s surveillance program. Only 42% of those who use Facebook and 41% of Twitter users felt comfortable discussing this same issue through social media.

Exploring the conditions under which people are willing to speak

Previous research showed that when people decide whether to speak out about an issue, they rely on reference groups—friendships and community ties—and weigh their opinion relative to these groups before speaking out in a setting. Other factors also play a role in people’s willingness to discuss issues. Our survey found that if people had a strong interest in the topic of the Snowden-NSA revelations, held a strong opinion, and felt knowledgeable about it, they were generally more willing to join a conversation about this issue.

What follows is our detailed exploration of the various circumstances that might affect someone’s willingness to speak about issues—in this case, the Snowden-NSA revelations.

In most settings, people’s level of interest in the Snowden-NSA revelations was related to their willingness to discuss this topic

In the summer of 2013, interest in information leaked by Edward Snowden about the U.S. government’s telephone and digital surveillance programs was high.

In our survey, respondents were asked how interested they were in debates about “a government program with the aim of collecting information about people’s telephone calls, emails, and other online communications.” Some 60% of American adults reported they were very or somewhat interested in this topic. Only 20% of Americans reported that they were not interested at all.

Using regression analysis to control for demographic differences, we found that someone who was “very interested” in the government surveillance program was 1.78 times more likely to be willing to join a conversation at a community meeting than someone who has no interest at all (See Appendix, Table B).

Similarly, compared with someone who was uninterested in this topic, someone who was very interested was 2.64 times more likely to speak up during a conversation with friends at a restaurant, and 2.88 times more likely to speak up when talking with family at dinner.

People’s level of interest in the Snowden-NSA story was not related to willingness to speak up in the workplace or on Facebook. The regression analyses showed that the interested and the uninterested were equally as likely to say they would voice their opinions on Facebook and at work.11

Those with more fervent opinions about the Snowden-NSA story were more likely to say they would speak out

In addition to asking about their interest in the Snowden-NSA story, we asked whether respondents favored or opposed “a government program to collect nearly all communications in the U.S. as part of anti-terrorism efforts?” Some 37% of Americans strongly or somewhat favored the surveillance programs and 52% strongly or somewhat opposed them. Another 10% said they didn’t know or refused to answer the question.12

We found that those who had stronger opinions on the topic of the Snowden-NSA revelations were more willing to speak out on this issue at public meetings, with family over dinner, and on Facebook (See Appendix, Table B). In comparison with those with less intense opinions, someone who either “strongly” favors or opposes the collection of domestic communications as part of government surveillance program was 1.56 times more likely to be willing to speak out at a public meeting, 1.35 times more likely to be would willingly discuss the issue with family over dinner, and 2.40 times more likely to have said they would join a conversation on Facebook.

Those who felt more knowledgeable were more willing to discuss the Snowden-NSA story

When a new, potentially important issue appears in the news, those who feel knowledgeable tend to show greater willingness to have a conversation with others. Indeed, feeling knowledgeable about this issue increased the likelihood that someone would be willing to join a conversation about the government’s surveillance program in all of the settings we explored.

In this survey, participants were asked to report on how knowledgeable they felt about the debate surrounding “government programs aimed at collecting information about people’s calls, emails and other online communication.”

Some 54% of adults reported that they felt very or somewhat knowledgeable about the government surveillance programs and 45% said they felt they had little or no knowledge of this topic.

Compared with someone who did not feel that they had any knowledge about the topic, those who described themselves as “very knowledgeable” were 2.68 times more likely to join a conversation at a public meeting, 3.19 times more likely in the workplace, 2.01 times more likely with friends at a restaurant, 1.79 times more likely over dinner with family, and 2.36 times more likely on Facebook (See Appendix, Table B).

People’s awareness of the opinions of those around them: Those who use social media tend to be more aware of others’ views

The level of awareness that people have of other people’s opinions plays a significant role in how willing they are to share their opinions. It has long been established that when people are surrounded by those who are likely to disagree with their opinion, they are more likely to self-censor.

We examined the awareness that people felt they had about the opinions of family, friends, coworkers, and others about the Snowden-NSA story—and the degree to which people think these other connections agree or disagree with them. We find that people were most likely to say they were aware of others’ views when it involved a very close relationship, such as a spouse/partner or close friends. Fully 96% of those who are married or living with a partner believe they know their spouse’s/partner’s opinion on the topic of the government’s surveillance program.

For other kinds of relationships, though, there was more variance in respondents’ answers.

- 96% of people who are married or living with a partner report that they know their partner’s opinion.

- 88% of people reported knowing the opinions of their close friends.

- 87% of people feel they know the opinions of their family members.

- 80% of people who are employed reported knowing the opinions of their coworkers.

- 62% of people feel they know their neighbors’ opinions on this issue.

The awareness that people have of the opinions of their followers on social media tends to be lower than for most other types of relationships.

- Of Facebook users, 76% felt they knew the opinions of people in their network.

- Of Twitter users, 68% felt they knew the opinions of those who followed them.

Interestingly enough, social media users are more likely than others to report they are aware of the opinions of different people in their lives.

- 93% of Twitter users and 90% of Facebook users say they know the opinions of family members on the Snowden-NSA issue. This compares with 82% of non-internet users and 84% of internet users who do not use social media.

- 94% of Twitter users and 91% of Facebook users say they are aware of their close friends’ opinions on the Snowden-NSA topic. This compares with 82% of non-internet users and 85% of internet users who do not use these social media sites.

- 66% of Facebook users, and 71% of Twitter users say they know their neighbors’ opinions about the government’s surveillance programs. This compares with 60% of internet users who are not social media users.

The more social media platforms people use, the greater their awareness of opinions in their extended network. When asked to report on the opinions of the people in their Facebook network, 79% of Facebook users say they know the opinions of their Facebook friends. Of those who use Twitter and Facebook, 86% say they know the opinions of their Facebook friends.

One exception to the trend of internet users knowing more about those in their social networks is coworkers. Employed non-internet users tend to be a bit more aware of colleagues’ opinions than internet users. Some 85% of employed non-internet users say they are aware of their coworkers’ opinions, compared with 78% of internet users who do not use social media, 82% of Facebook users, and 84% of Twitter users who say they know the opinions of coworkers.

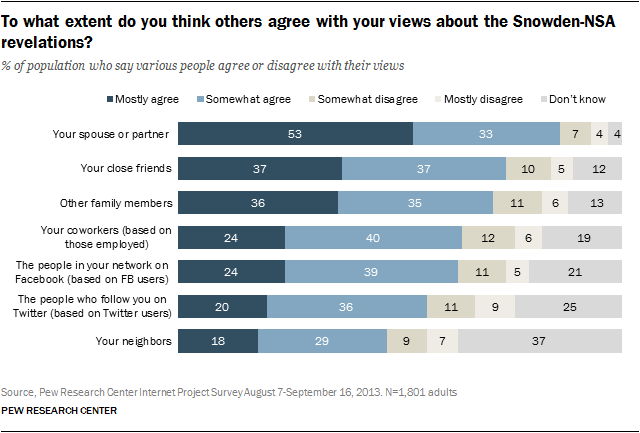

How much people think they agree with the views of family members, friends, and colleagues

A crucial issue affecting whether someone will be willing to discuss a controversial subject is the degree to which a speaker feels his or her views line up with their audience. Some research has found that people have a tendency to associate with those who share their opinions. That is, even though broad public opinion may be divided on an issue, people are more likely to believe that their acquaintances support their position on that issue. Some of this similarity is a result of homophily, the penchant for people to associate with people like themselves; some is a result of the influence of opinion leaders; and some is a result of the tendency for people to assume more agreement than there is in reality.13

This survey shows that people have different notions about how much agreement they have with close family and friends, compared with associates that are less close, including those in their Facebook and Twitter networks. In addition, the more socially distant an audience is, the more likely it is that respondents did not know the views of their potential audience.

- 86% of those who are married or living with a partner believe their spouse’s/partner’s views “mostly” or “somewhat” agree with theirs about the Snowden-NSA revelations.

- 74% of all adults believe their close friends “mostly” or “somewhat” agree with their views about the Snowden-NSA revelations.

- 70% of all adults believe their family members “mostly” or “somewhat” agree with their views about the Snowden-NSA revelations. (This includes family members who are not a spouse or partner.)

- 64% of those who are employed think that their coworkers agree with their position on the government’s surveillance program.

- 63% of Facebook users believe that the people in their Facebook network “mostly” or “somewhat” agree with their views about the Snowden-NSA revelations.

- 56% of Twitter users believe that the people who follow them on Twitter “mostly” or “somewhat” agree with their views.

- 47% of all adults believe their neighbors “mostly or “somewhat” agree with their views.

Facebook users were more likely to feel that friends, family and acquaintances share their opinion. Regression analysis was used to control for demographic characteristics, interest in the topic, knowledge of the topic, strength of opinion on this issue, and social media use when predicting agreement with different types of acquaintances. We find that Facebook use is related to perceived agreement with the opinions of friends, family, and other acquaintances (See Appendix, Table C). Users who contribute content and read other people’s content on Facebook are more likely to believe that other people agree with their opinions.

- Someone who frequently uses the “like button” on Facebook content contributed by other Facebook users (they use it a few times per day) is 1.88 times more likely to feel that their family members share their views, and they are 1.72 times more likely to feel they share the opinions of people in their Facebook network, when compared to those who do not use the like button.

- Someone who updates their status on Facebook a half dozen times per month, compared to someone who does not update at all, is 1.10 times more likely to feel they share the opinions of family members, and 1.13 times more likely to share the opinions of their close friends.

It is not immediately clear from our study why Facebook activities are related to perceptions of higher levels of agreement with Facebook friends. Two possible explanations are related to “cyberbalkanization.”14 Facebook friendship networks may be more likely to consist of similar people, or their opinions may become more similar over time. However, we expect that a third option is most likely. Reading content contributed by other users, actively clicking the like button, as well as receiving feedback in response to status updates, provides for enhanced observation of others and confirmatory feedback from friends and family. In addition to people choosing to associate with people on Facebook who are similar to them, Facebook makes people more aware of existing opinion similarity.

The spiral of silence persists online and offline: People are less likely to speak when they think their audiences disagree with them

In many settings, it is not well understood how much people self-censor in response to such social pressures. Some early research has shown that the rate of self-censorship on Facebook is very high. One study found that people on Facebook start to write, but ultimately fail to share, 33% of posts and 13% of comments.15 This self-censorship has been described as a response to “context collapse”16—that is, people deciding not to share content that is of personal interest, but is unlikely to appeal to a social media audience that focuses on narrow topics.

However, there is another possibility. Some self-censorship might be the result of feeling that social media followers are likely to object or disagree with their opinion. In other words, a user might know the content is relevant to some followers, but decide not to share it on social media for fear of inviting disagreement among their followers.

- At work, those who felt their coworkers agreed with their opinion were 2.92 times more likely to say they would join a conversation on the Snowden-NSA topic than for those who did not feel they would agree with their coworkers’ opinion on the government’s surveillance program.

- At a family dinner, those who felt that family members agreed with their opinion were 1.90 times more likely to speak out about Snowden-NSA issue.

- At a restaurant with friends, those who felt that their close friends agreed with their opinion were 1.42 times more likely to share their opinions.

- On Facebook, if the person felt that people in their Facebook network agreed with their position on this issue, they were 1.91 times more likely to join a conversation about Snowden-NSA.

However, the social pressure from some types of relationships carried across multiple settings. For example, when at a restaurant with friends, people’s willingness to speak out was tied to the opinions of their family members. That might possibly be the case because close friends and family tend to have similar opinions. Or it might be the case because a meal with friends at a restaurant may include family. Additionally, it might be the case because people felt they knew they had supportive family members kind of “standing by” them. Whatever the reason, those who had family that shared their opinions were 1.42 times more likely to join a conversation about this issue at a restaurant with friends, even when friends did not agree.

When social media followers disagree, people are more likely to self-censor offline

In some offline settings, we found that when compared to non-internet users, online Americans in general were more willing to join a conversation about the Snowden-NSA story. An internet user was 2.41 times more likely to be willing to have a conversation at work, and 1.49 times more likely to have a conversation with family about the government’s surveillance program. A typical LinkedIn user, who accesses the site a half dozen times per month, was 1.20 times more likely to discuss this political issue in a restaurant with friends than other internet users or non-internet users.

However, we found many more examples to suggest that social media use is associated with a lower likelihood that people would have a conversation on a political issue in physical settings. When controlling for demographic traits such as gender, age, race, educational attainment, and marital status, as well as variation in interest, opinion strength, knowledge, and other sources of information exposure we found:

Facebook users were less willing to discuss the government’s surveillance program at a public meeting. Someone who uses Facebook several times per day is 0.53 times less likely to be willing to discuss the Snowden-NSA topic at a public meeting than someone who does not use the Facebook platform at all.

Instagam users were less likely to say they would discuss the government’s surveillance program at a family dinner or at a restaurant with friends. A typical Instagram user (who uses the platform several times per day) is 0.49 times less likely to be willing to join a conversation about the government’s surveillance program with family at dinner, and 0.44 times less likely with friends at a restaurant, than for people who do not use Instagram.

It is not completely clear why some users of social media would be less willing to share an opinion in physical settings. However, since we have controlled for demographic differences, and variation in interest, opinion strength, knowledge, and other sources of information exposure, it is possible that this heightened self-censorship might be tied to social media users’ greater awareness of the opinions of others in their network (on this and other topics). Thus, they could be more aware of views that oppose their own.

If their use of social media gives them broader exposure to the views of friends, family, and workmates, this might increase the likelihood that people will choose to withhold their opinion because they know more about the people who will object to it.

There are two additional examples from our data that most clearly demonstrate this relationship.

Twitter users were less willing to engage in a conversation in the workplace, especially if they felt those following them on Twitter did not agree with their opinion on the government’s surveillance program. A typical Twitter user, who uses the platform several times per day, was0.24 times less likely to be willing to join a conversation on the Snowden-NSA story at work than other internet users. However, if they felt their Twitter followers agreed with their opinion, then they were only 0.69 times less likely to be willing to engage in a discussion at work. This relationship was in addition to the lower likelihood that someone would speak out at work if they felt their coworkers did not share their opinions.

Facebook users and those who do not feel their Facebook friends agree with their opinion were less willing to engage in an in-person discussion with friends on this issue. A typical Facebook user, someone who accesses the platform several times per day, is 0.53 times less likely to be willing to discuss the government’s surveillance program with friends at a restaurant than those who do not use Facebook. If they feel that people in their Facebook network agree with their opinion, they are only 0.74 times less likely to discuss this topic in-person with friends when compared with those who do not use Facebook at all. This relationship is in addition to the lower likelihood that people have of speaking out when at a restaurant if they do not believe their close friends agree with their opinion. Facebook likely increases awareness of the diversity of opinions in people’s friendship network beyond their closest friends. This awareness reduces certainty in the similarity of opinions between friends and increases the fear of isolation or ostracism that might result from sharing a divergent point of view.

Social media use does encourage more discussion among some groups

While social media use may be linked to a muting effect on discussions of political issues in some physical settings, for some it is associated with new opportunities for discussion.

Unsurprisingly, the heaviest users of Facebook, in terms of frequency of commenting and private messaging, were also those who were most likely to be willing to discuss the government’s surveillance program on the Facebook platform. However, for all but the most intensive users, the relationship to discussing political issues is relatively small. Someone who comments on other people’s Facebook statuses, photos, links, and other content about twice per week was only 1.04 times more likely to be willing to discuss the Snowden-NSA story on Facebook in comparison with someone who does none of these things.

One type of social media use was associated with a lower level of willingness to join a conversation about public affairs on Facebook. Possibly as a result of the diversity they observed through images contributed to Instagram, Instagram users were less willing than other Facebook users to use the Facebook platform to discuss the government’s surveillance program. A typical Instagram user, someone who uses the platform several times per day, was 0.49 times less likely to be willing to discuss the government’s surveillance program on Facebook.

There are some indications that Facebook may democratize discussion of political issues in at least some respects. Unlike many physical settings, on Facebook, those with fewer years of formal education were the most likely to speak up about an important political issue. When discussing political issues with friends at a restaurant, and family over dinner, it is those with the most education who are most willing to join in on a conversation. The opposite is true on Facebook. Those with the most years of formal education are more likely to fall silent when discussing the Snowden-NSA issue. Someone with only a high school diploma was 1.34 times less likely to be willing to join a conversation on Facebook about the government’s surveillance program when compared to someone with an undergraduate university degree. Similarly, on Facebook, women are as likely as men to feel comfortable discussing an important political issue. This contrasts with discussions at community meetings and at work where women tend to feel less comfortable discussing a political issue such as the government’s surveillance program.