Stereotypes of Asians in the U.S. as foreigners and a model minority drive discrimination

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to understand Asian Americans’ experiences with discrimination in the United States and their views of anti-Asian racism in the country. This report is the latest in the Center’s in-depth analysis of public opinion among Asian Americans.

The data in this report comes from two main sources. The first is a nationally representative survey of 7,006 Asian adults exploring the experiences, attitudes and views of Asians living in the U.S. on several topics, including discrimination and racism in America, identity, affirmative action, global affairs, policy priorities and religious identities. The survey sampled U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic ethnicity. It was offered in six languages: Chinese (Simplified and Traditional), English, Hindi, Korean, Tagalog and Vietnamese. Responses were collected from July 5, 2022, to Jan. 27, 2023, by Westat on behalf of Pew Research Center.

The Center recruited a large sample to examine the diversity of the U.S. Asian population, with oversamples of the Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Korean and Vietnamese populations. These are the five largest origin groups among Asian Americans. The survey also includes a large enough sample of self-identified Japanese adults, making findings about them reportable. In this report, the six largest ethnic groups include those who identify with one Asian ethnicity only, either alone or in combination with a non-Asian race or ethnicity. Together, these six groups constitute 81% of all U.S. Asian adults, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of the Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey (ACS), and are the six groups whose attitudes and opinions are highlighted throughout the report.

Survey respondents were drawn from a national sample of residential mailing addresses, which included addresses from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Specialized surname list frames maintained by the Marketing Systems Group were used to supplement the sample. Those eligible to complete the survey were offered the opportunity to do so online or by mail with a paper questionnaire. For more details, refer to the survey methodology. For questions used in this analysis, refer to the topline questionnaire.

Findings for less populous Asian origin groups in the U.S., those who are not among the six largest Asian origin groups, are grouped under the category “other” and are included in the overall Asian adult findings in the report. These ethnic origin groups each make up about 2% or less of the Asian population in the U.S., making it challenging to recruit nationally representative samples for each origin group. The group “other” includes those who identify with one Asian ethnicity only, either alone or in combination with a non-Asian race or Hispanic ethnicity. Findings for those who identify with two or more Asian ethnicities are not presented by themselves in this report but are included in the overall Asian adult findings.

The second data source for this report is focus groups. Survey results are complemented by findings from 66 pre-survey focus groups of Asian adults, conducted from Aug. 4 to Oct. 14, 2021, with 264 recruited participants from 18 Asian origin groups. Focus group discussions were conducted in 18 different languages and moderated by members of their origin groups. In the focus groups, participants discussed their experiences with discrimination in the United States, and some quotations are used in this report. Quotations are not necessarily representative of the majority opinion in any particular group living in the U.S. or of Asian Americans overall. Quotations may have been edited for grammar, spelling and clarity.

Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. The Center’s Asian American portfolio was funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from The Asian American Foundation; Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the Henry Luce Foundation; the Doris Duke Foundation; The Wallace H. Coulter Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Long Family Foundation; Lu-Hebert Fund; Gee Family Foundation; Joseph Cotchett; the Julian Abdey and Sabrina Moyle Charitable Fund; and Nanci Nishimura.

We would also like to thank the Leaders Forum for its thought leadership and valuable assistance in helping make this survey possible.

The strategic communications campaign used to promote the research was made possible with generous support from the Doris Duke Foundation.

The terms Asians, Asians living in the United States, U.S. Asian population and Asian Americans are used interchangeably throughout this report to refer to U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

Ethnicity and ethnic origin labels, such as Chinese and Chinese origin, are used interchangeably in this report for findings for ethnic origin groups, such as Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean or Vietnamese. For this report, ethnicity is not nationality. For example, Chinese in this report are those self-identifying as of Chinese ethnicity, rather than necessarily being a current or former citizen of the People’s Republic of China. Ethnic origin groups in this report include those who identify as one Asian ethnicity only, either alone or in combination with a non-Asian race or ethnicity. Responses for Asian adults who identify with two or more Asian ethnic origin groups are included in the total but not shown separately.

Less populous Asian origin groups in this report are those who self-identify with ethnic origin groups that are not among the six largest Asian ones. They are grouped under the category “other” when displayed in charts. The term includes those who identify with only one Asian ethnicity, either alone or in combination with a non-Asian race or ethnicity. These ethnic origin groups each represent about 2% or less of the overall Asian population in the U.S. For example, those who identify as Burmese, Hmong or Pakistani are included in this category. Survey findings from these groups are unreportable on their own due to small sample sizes, but collectively they are reportable under this category.

Region and regional origin labels, such as East Asian and East Asian origin, are used interchangeably in this report for findings for regional origin groups, such as East Asian (which includes Chinese, Japanese, Korean or other East Asian origins), South Asian (which includes Bangladeshi, Indian, Nepali, Pakistani or other South Asian origins) or Southeast Asian (which includes Cambodian, Filipino, Hmong, Vietnamese or other Southeast Asian origins) adults. Regional Asian origin groups in this report include those who self-identify with an Asian ethnic origin group or multiple Asian ethnic origin groups that belong to one Asian region only. Responses for Asian adults who identify with ethnic origin groups that belong to two or more Asian regions are included in the total but not shown separately.

Immigrants in this report are people who were born outside the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories. Immigrant, foreign born and born abroad are used interchangeably to refer to this group.

Naturalized citizens are immigrants who are lawful permanent residents who have fulfilled the length of stay and other requirements to become U.S. citizens and who have taken the oath of citizenship.

U.S. born refers to people born in the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories.

Among immigrants, there are two distinct immigrant generation groups in this report:

- First generation refers to people who were born outside the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories and immigrated to the U.S. when they were 18 or older. Throughout the report, the term first generation and the phrase immigrants who came to the U.S. as adults are used interchangeably.

- 1.5 generation refers to people who were born outside the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories and immigrated to the U.S. when they were younger than 18 years old. Throughout the report, the term 1.5 generation and the phrase immigrants who came to the U.S. as children are used interchangeably.

Among U.S. born, there are two distinct immigrant generation groups in this report:

- Second generation refers to people born in the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories with at least one foreign-born (immigrant) parent. Throughout the report, the term second generation and the phrase U.S.-born children of immigrant parents are used interchangeably.

- Third or higher generation refers to people born in the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories with both parents born in the 50 states, D.C., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories.

Primary language is a composite measure based on self-described assessments of speaking and reading abilities. People who are origin language dominant are more proficient in the Asian origin language of their family or ancestors than in English (i.e., they speak and read their Asian origin language “very well” or “pretty well” but rate their ability to speak and read English lower). Bilingual refers to those who are proficient in both English and their Asian origin language. People who are English dominant are more proficient in English than in their Asian origin language.

Throughout this report, Democrats refers to respondents who identify politically with the Democratic Party or those who are independent or identify with some other party but lean toward the Democratic Party. Similarly, Republicans includes both those who identify politically with the Republican Party and those who are independent or identify with some other party but lean toward the Republican Party.

In this report, Asian adults who are single race include those who self-identify as Asian and no other non-Asian race or origin. Asian adults who are two or more races include those who self-identify as Asian and at least one other non-Asian race or origin (such as White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or some other non-Asian race or origin). Racial identity groups were constructed regardless of Hispanic self-identity.

The spike in incidents of anti-Asian discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic sparked national conversations about race and racial discrimination concerning Asian Americans.1 But discrimination against Asian Americans is not new.2 From the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, to denial of the right to become naturalized U.S. citizens until the 1940s, to the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, to backlash against Muslims, Sikhs and South Asians after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, most Asian Americans have faced discrimination and exclusion while being treated as foreigners throughout their long history in the United States.

At the same time, Asian Americans have often been upheld as a model for how other racial and ethnic minorities should behave – especially in comparison with Black Americans and Latinos.3 Despite the socioeconomic diversity among U.S. Asians, they are commonly portrayed as educationally and economically successful, hardworking, deferential to authority, unemotional and lacking in creativity.4 This “model minority” stereotype has placed Asian Americans at the center of debates about meritocracy, selective admissions to elite institutions and affirmative action.

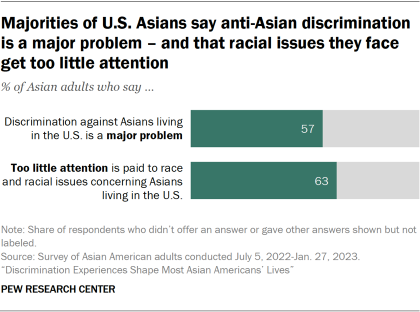

Today, 57% of Asian adults see discrimination against Asians living in the U.S. as a major problem. And 63% say too little attention is paid to race and racial issues concerning Asian Americans, according to a new analysis of a multilingual, nationally representative survey of 7,006 Asian adults conducted from July 5, 2022, to Jan. 27, 2023.

Key findings from the survey

For many Asian Americans, discrimination experiences are not just single events, but instead come in several often-overlapping forms. Overall, the survey showed that most Asian Americans experience discrimination in three broad ways: Those related to being treated as a foreigner (even if they were born in the U.S.); being seen as a model minority; and other discrimination incidents in day-to-day encounters or because of their race or ethnicity.

Jump to chapters on …

- Asian Americans’ experiences with discrimination in their daily lives

- Asian Americans and the “forever foreigner” stereotype

- Asian Americans and the “model minority” stereotype

- Asian Americans and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Asian Americans’ views of anti-Asian discrimination in the U.S. today

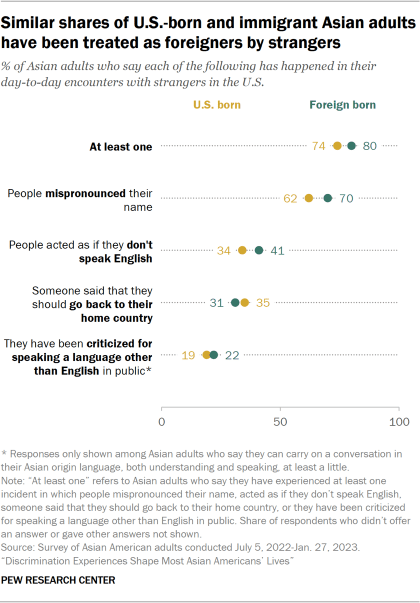

- 78% of Asian adults have been treated as a foreigner in some way, even if they are U.S. born. This includes Asian adults who say that in day-to-day encounters with strangers in the U.S., someone has told them to go back to their home country, acted like they can’t speak English, criticized them for speaking a language other than English in public, or mispronounced their name.5

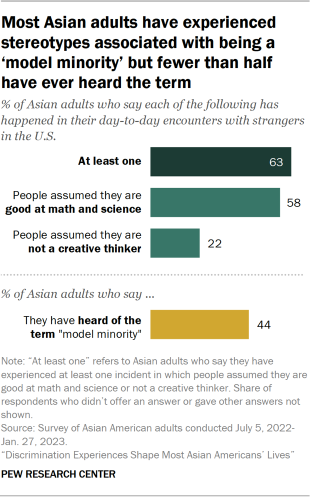

- 63% of Asian adults have experienced incidents where people assume they are a model minority. This includes Asian Americans who say that in day-to-day encounters with strangers in the U.S., people have assumed that they are good at math and science or that they are not creative thinkers.

- 35% of South Asian adults say they have been held back at a security checkpoint for a secondary screening because of their race or ethnicity. This is higher than the shares among Southeast (15%) and East (14%) Asian adults.6 Additionally, Asian American Muslims are more likely than some other major religious groups to say this has happened to them.

- 32% of Asian adults say they know another Asian person in the U.S. who has been threatened or attacked because of their race or ethnicity since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Across regional origin groups, about one-third of East (36%) and Southeast (33%) Asian adults say they know someone with this experience, as do 24% of South Asian adults.

- In many cases, Asian adults who grew up in the U.S. are more likely than those who immigrated as adults to say they have experienced discrimination incidents. For example, about half or more of U.S.-born Asian adults and immigrants who came to the U.S. as children (1.5 generation) say they have been called offensive names in daily interactions with strangers, compared with 20% of those who immigrated as adults (first generation).7 This could be for a number of reasons, including recognizing discrimination more than other Asian adults, having more non-Asian friends, or being racialized in America during adolescence.8

- 68% of Asian adults who grew up in the U.S. say they rarely or never talked with family about the challenges they might face because of their race or ethnicity when growing up.9 Meanwhile, 31% say their family sometimes or often discussed it.

In sum, the survey asked Asian Americans if they have personally experienced 17 specific discrimination incidents in day-to-day encounters or because of their race or ethnicity. It also asked more broadly if they have ever experienced racial discrimination.

- About nine-in-ten Asian Americans have personally experienced at least one of the 17 discrimination incidents asked about in the survey. Across these incidents, Asian Americans are most likely to say that strangers mispronounced their name (68%) or assumed that they are good at math and science (58%). And about half of Asian adults say they have experienced four incidents or more.

- 58% of Asian adults say they have ever experienced racial discrimination or been treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity. This includes 53% who say they experience racial discrimination from time to time and 5% who say they experience it regularly.

Read the Appendix for the list of the 17 discrimination incidents asked about in the survey. This is not an exhaustive list of all possible discrimination experiences. Some Asian adults who said “no” to all of these may still have experienced some form of discrimination not captured by the survey.

Most Asian Americans have been treated as foreigners in some way, no matter where they were born

Many Asian Americans face the experience of being treated as a foreigner, no matter their birthplace, citizenship status or strength of their ties to the U.S.

About equal shares of U.S.-born and immigrant Asian adults say they have had experiences in which they are treated as foreigners:

- 70% of immigrants and 62% of U.S.-born Asian adults say people have mispronounced their name.

- 41% of immigrants and 34% of U.S.-born adults say people have acted as if they don’t speak English.

- 31% of immigrants and 35% of U.S.-born adults say someone has told them to go back to their home country.

- And among those who can speak their Asian origin language, 22% of immigrants and 19% of U.S.-born adults say someone has criticized them for speaking a non-English language in public.

These experiences persist even among Asian adults whose families have lived in the U.S. for multiple generations.

- 37% of second-generation Asian adults (the U.S.-born children of immigrant parents) say someone has told them to go back to their home country, compared with 26% of first-generation Asian adults (those who immigrated to the U.S. as adults).

Whether or not immigrants are naturalized U.S. citizens, many still experience being treated as a foreigner. And in some cases, higher shares of citizens than noncitizens say these incidents have happened to them:

- 34% of Asian immigrants who are naturalized U.S. citizens say someone has told them to go back to their home country, compared with 26% of Asian immigrants who have not obtained citizenship.

(Explore more about the “forever foreigner” stereotype and Asian Americans in Chapter 2.)

Most Asian Americans have been subjected to ‘model minority’ stereotypes, but many haven’t heard of the term

Another experience many Asian Americans encounter is being stereotyped as a model minority, no matter their background. This stereotype often does not align with the lived experiences and socioeconomic backgrounds of many Asians in the U.S. Research on the model minority myth has also pointed to its negative impact on attitudes and expectations made of other racial and ethnic groups.10

- Immigrant generation: About three-quarters each of 1.5- and second-generation Asian adults say they have had at least one experience in which people have assumed they are good at math and science or not a creative thinker. Smaller shares of first-generation (56%) and third- or higher-generation (55%) Asian adults say the same.

- Education: 72% of Asians with a postgraduate degree say they have been subjected to at least one of the model minority stereotypes, compared with 54% of those with a high school degree or less.

- Income: 73% of Asian adults with a family income of $150,000 or more say this has happened to them, compared with 51% of Asian adults with a family income of less than $30,000.

Asian Americans’ awareness of the term ‘model minority’

Despite most Asian Americans saying they have been subjected to stereotypes associated with the idea of being a model minority, fewer than half (44%) say they have heard of the term. The groups who have experienced model minority stereotypes are also more likely to say they are familiar with the term:

- Experiences of the stereotype: Overall, Asian adults who have experienced at least one model minority stereotype are more likely to be familiar with the label, compared with those who have not faced either of these experiences (51% vs. 32%).

- Immigrant generation: About six-in-ten Asian adults who are 1.5 generation (60%) and second generation (62%) say they have heard of the term. By comparison, 40% of third- or higher-generation and 32% of first-generation Asian adults say the same.

- Education: 53% of Asian Americans with a postgraduate degree know the term “model minority,” compared with 30% of those with a high school degree or less.

- Income: 54% of Asian adults who make $150,000 or more say they are familiar with the term, compared with 29% of those who make less than $30,000.

- Age: 56% of Asian adults younger than 30 have heard the term “model minority.” About 37% of those 65 and older say the same.

Asian Americans’ views of the ‘model minority’ label

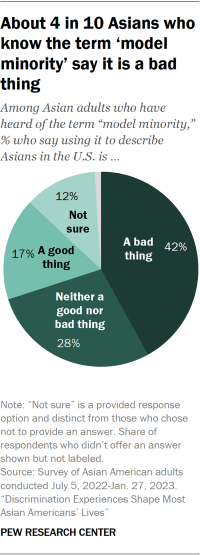

Among Asian adults who have heard of the term “model minority,” 42% say describing Asians as a model minority is a bad thing, while 28% say it is neither a good nor bad thing, 17% say it is a good thing and 12% are not sure.

Views among Asian adults who have heard of the model minority label vary across some demographic groups:

- Immigrant generation: 62% of second-generation Asian adults say the model minority label is a bad thing. By comparison, 43% of 1.5-generation and 26% of first-generation Asian adults say the same.

- Age: 66% of Asian adults under 30 view the model minority label negatively, while 8% view it positively. On the other hand, 36% of Asian adults 65 and older say the label is a good thing, while 17% say it is a bad thing.

- Party: 52% of Asian adults who identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party say describing Asians as a model minority is a bad thing, compared with 17% of Republicans and Republican leaners. Among Republicans, 31% say calling Asian Americans a model minority is a good thing, while only 12% of Democrats say the same.

(Explore more about the “model minority” stereotype and Asian Americans’ views of it in Chapter 3.)

Experiences with other daily and race-based discrimination incidents

- 40% of Asian adults say they have received poorer service than other people at restaurants and stores. More than four-in-ten Asian adults who have a bachelor’s degree or more say they have had this experience, compared with about one-third with some college experience or less.

- 37% of Asian adults say in day-to-day encounters with strangers, they have been called offensive names. About six-in-ten U.S.-born Asian adults (57%) say this, compared with 30% of Asian immigrants.

- 11% of Asian adults say have been stopped, searched or questioned by the police because of their race or ethnicity. Responses differ by how others perceive their racial or ethnic identity. Asian adults who are perceived as non-Asian and non-White (which includes those who say they are perceived as “mixed race or multiracial” or “Arab or Middle Eastern,” among others) are more likely to say they have had this experience, compared with those who are perceived as Asian or Chinese.11

In their own words: Key findings from qualitative research on Asian Americans and discrimination experiences

In 2021, Pew Research Center conducted 66 focus groups of Asian Americans across 18 different Asian origin groups. In the focus groups, some participants shared their experiences with discrimination that elaborate on our survey findings.

- Many participants talked about their experiences being bullied, harassed or called slurs and other offensive names because of their race or ethnicity. (Read more about these experiences in Chapter 1)

- Some participants – particularly those who are South Asian – talked about facing discriminatory backlash after the events of Sept. 11, 2001. (Chapter 1)

- We also asked participants what they would do if their close friend was told that they don’t belong here and to go back to their “home country.” Participants offered a range of responses including offering emotional support, telling them to walk away, record and report the incident, and speak up or fight back. (Chapter 2)

- Participants also shared their perspectives on the model minority stereotype. Some shared how it reinforces harmful social pressures and treats Asians as monolithic. Others had more mixed feelings, and some had positive impressions of how the stereotype characterizes Asian Americans. (Chapter 3)

- Participants discussed their experiences of being discriminated against since the coronavirus outbreak in 2020, including being shamed, harassed or attacked in public and private spaces. (Chapter 4)

From exclusion through World War II

Asian Americans have faced discrimination throughout their history in the United States. In the 1800s, Asians were brought to the U.S. as indentured laborers amid the emancipation of African slaves. While playing integral roles in projects like the Transcontinental Railroad, Asian immigrants faced emerging anti-Asian sentiments and exclusion, with beliefs that Asians were creating unjust labor competition and endangering mainstream American society. Congress passed laws to exclude Asian immigrants including the 1875 Page Law, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the 1917 Asiatic Barred Zone Act, among others.

In the 1920s, a series of Supreme Court cases reaffirmed previous laws that clarified that Asian immigrants, including South Asians, are not “free White persons” and therefore were excluded from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens. This period also saw legislation that outlawed interracial marriage, including the 1922 Cable Act which stipulated that if U.S.-born women married “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” they would lose their own citizenship. Additionally, beginning in 1913, some states restricted Asian immigrants as well as U.S.-born Asian Americans from the right to own and lease land. Many states upheld these laws until the 1950s, and Florida’s law was only repealed in 2018.

Beginning in 1942, Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II, driven by the belief that they were spies and enemies. Throughout this period, Asians experienced discrimination in the labor market and other areas of life and were treated as foreign people who were not accepted as American.

From post-World War II to the present day

In the postwar period, immigration patterns changed. The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act abolished quotas and allowed immigration from Asia to increase. The Vietnam War and other conflicts in Southeast Asia brought refugees from the region to the U.S. in higher numbers. And the 1990 Immigration Act raised immigration ceilings and allowed the flow of Asian immigrants in professional occupations to expand.

In this period, other stereotypes about Asian Americans began to emerge. Starting from the 1960s, Asian Americans were portrayed in popular media as overachievers, intellectually and financially successful, and a group that rarely complained or spoke up. Amid the Civil Rights Movement, images of Asian Americans as a successful or “model” minority, especially in comparison with other racial or ethnic groups, proliferated. Two high-profile examples of this include the 1966 New York Times Magazine article calling Japanese Americans a “success story” and the 1987 Time magazine cover story characterizing Asian Americans as “whiz kids.”

Global tensions regularly shaped the experiences of the U.S. Asian population. The fear of economic competition with Asian countries in the postwar period contributed to rising resentment toward Asian Americans and resulted in tragedies such as the murder of Vincent Chin. In the aftermath of Sept. 11, Muslims, Sikhs, Arabs and South Asians in the U.S. became targets of racial profiling and hate crimes due to anti-Muslim sentiments. Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic intensified anti-Asian sentiment, with many Asian Americans facing racist attacks, threats and bias across the country.