Introduction

No single experience defines what it means to be Asian in the United States today. Instead, Asian Americans’ lived experiences are in part shaped by where they were born, how connected they are to their family’s ethnic origins, and how others – both Asians and non-Asians – see and engage with them in their daily lives. Yet despite diverse experiences, backgrounds and origins, shared experiences and common themes emerged when we asked: “What does it mean to be Asian in America?”

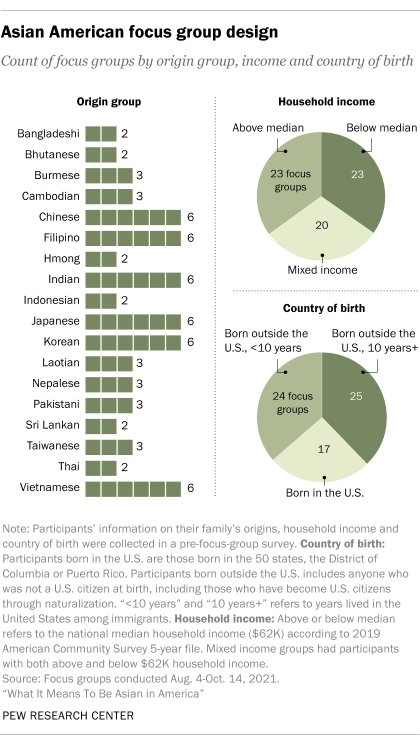

In the fall of 2021, Pew Research Center undertook the largest focus group study it had ever conducted – 66 focus groups with 264 total participants – to hear Asian Americans talk about their lived experiences in America. The focus groups were organized into 18 distinct Asian ethnic origin groups, fielded in 18 languages and moderated by members of their own ethnic groups. Because of the pandemic, the focus groups were conducted virtually, allowing us to recruit participants from all parts of the United States. This approach allowed us to hear a diverse set of voices – especially from less populous Asian ethnic groups whose views, attitudes and opinions are seldom presented in traditional polling. The approach also allowed us to explore the reasons behind people’s opinions and choices about what it means to belong in America, beyond the preset response options of a traditional survey.

The terms “Asian,” “Asians living in the United States” and “Asian American” are used interchangeably throughout this essay to refer to U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

“The United States” and “the U.S.” are used interchangeably with “America” for variations in the writing.

Multiracial participants are those who indicate they are of two or more racial backgrounds (one of which is Asian). Multiethnic participants are those who indicate they are of two or more ethnicities, including those identified as Asian with Hispanic background.

U.S. born refers to people born in the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, or other U.S. territories.

Immigrant refers to people who were not U.S. citizens at birth – in other words, those born outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents who were not U.S. citizens. The terms “immigrant,” “first generation” and “foreign born” are used interchangeably in this report.

Second generation refers to people born in the 50 states or the District of Columbia with at least one first-generation, or immigrant, parent.

The pan-ethnic term “Asian American” describes the population of about 22 million people living in the United States who trace their roots to more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. The term was popularized by U.S. student activists in the 1960s and was eventually adopted by the U.S. Census Bureau. However, the “Asian” label masks the diverse demographics and wide economic disparities across the largest national origin groups (such as Chinese, Indian, Filipino) and the less populous ones (such as Bhutanese, Hmong and Nepalese) living in America. It also hides the varied circumstances of groups immigrated to the U.S. and how they started their lives there. The population’s diversity often presents challenges. Conventional survey methods typically reflect the voices of larger groups without fully capturing the broad range of views, attitudes, life starting points and perspectives experienced by Asian Americans. They can also limit understanding of the shared experiences across this diverse population.

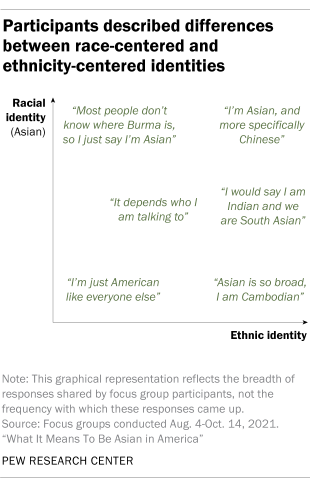

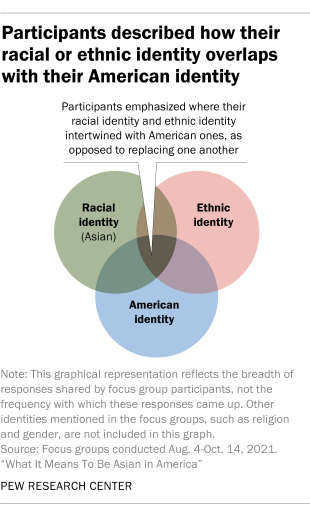

Across all focus groups, some common findings emerged. Participants highlighted how the pan-ethnic “Asian” label used in the U.S. represented only one part of how they think of themselves. For example, recently arrived Asian immigrant participants told us they are drawn more to their ethnic identity than to the more general, U.S.-created pan-ethnic Asian American identity. Meanwhile, U.S.-born Asian participants shared how they identified, at times, as Asian but also, at other times, by their ethnic origin and as Americans.

Another common finding among focus group participants is the disconnect they noted between how they see themselves and how others view them. Sometimes this led to maltreatment of them or their families, especially at heightened moments in American history such as during Japanese incarceration during World War II, the aftermath of 9/11 and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. Beyond these specific moments, many in the focus groups offered their own experiences that had revealed other people’s assumptions or misconceptions about their identity.

Another shared finding is the multiple ways in which participants take and express pride in their cultural and ethnic backgrounds while also feeling at home in America, celebrating and blending their unique cultural traditions and practices with those of other Americans.

This focus group project is part of a broader research agenda about Asians living in the United States. The findings presented here offer a small glimpse of what participants told us, in their own words, about how they identify themselves, how others see and treat them, and more generally, what it means to be Asian in America.

Illustrations by Jing Li

Publications from the Being Asian in America project

- Read the data essay: What It Means to Be Asian in America

- Watch the documentary: Being Asian in America

- Explore the interactive: In Their Own Words: The Diverse Perspectives of Being Asian in America

- View expanded interviews: Extended Interviews: Being Asian in America

- About this research project: More on the Being Asian in America project

- Q&A: Why and how Pew Research Center conducted 66 focus groups with Asian Americans

This is how I view my identity

One of the topics covered in each focus group was how participants viewed their own racial or ethnic identity. Moderators asked them how they viewed themselves, and what experiences informed their views about their identity. These discussions not only highlighted differences in how participants thought about their own racial or ethnic background, but they also revealed how different settings can influence how they would choose to identify themselves. Across all focus groups, the general theme emerged that being Asian was only one part of how participants viewed themselves.

The pan-ethnic label ‘Asian’ is often used more in formal settings

“I think when I think of the Asian Americans, I think that we’re all unique and different. We come from different cultures and backgrounds. We come from unique stories, not just as a group, but just as individual humans.”

Mali, documentary participant

Many participants described a complicated relationship with the pan-ethnic labels “Asian” or “Asian American.” For some, using the term was less of an active choice and more of an imposed one, with participants discussing the disconnect between how they would like to identify themselves and the available choices often found in formal settings. For example, an immigrant Pakistani woman remarked how she typically sees “Asian American” on forms, but not more specific options. Similarly, an immigrant Burmese woman described her experience of applying for jobs and having to identify as “Asian,” as opposed to identifying by her ethnic background, because no other options were available. These experiences highlight the challenges organizations like government agencies and employers have in developing surveys or forms that ask respondents about their identity. A common sentiment is one like this:

“I guess … I feel like I just kind of check off ‘Asian’ [for] an application or the test forms. That’s the only time I would identify as Asian. But Asian is too broad. Asia is a big continent. Yeah, I feel like it’s just too broad. To specify things, you’re Taiwanese American, that’s exactly where you came from.”

–U.S.-born woman of Taiwanese origin in early 20s

Smaller ethnic groups default to ‘Asian’ since their groups are less recognizable

Other participants shared how their experiences in explaining the geographic location and culture of their origin country led them to prefer “Asian” when talking about themselves with others. This theme was especially prominent among those belonging to smaller origin groups such as Bangladeshis and Bhutanese. A Lao participant remarked she would initially say “Asian American” because people might not be familiar with “Lao.”

“[When I fill out] forms, I select ‘Asian American,’ and that’s why I consider myself as an Asian American. [It is difficult to identify as] Nepali American [since] there are no such options in forms. That’s why, Asian American is fine to me.”

–Immigrant woman of Nepalese origin in late 20s

“Coming to a big country like [the United States], when people ask where we are from … there are some people who have no idea about Bhutan, so we end up introducing ourselves as being Asian.”

–Immigrant woman of Bhutanese origin in late 40s

But for many, ‘Asian’ as a label or identity just doesn’t fit

Many participants felt that neither “Asian” nor “Asian American” truly captures how they view themselves and their identity. They argue that these labels are too broad or too ambiguous, as there are so many different groups included within these labels. For example, a U.S.-born Pakistani man remarked on how “Asian” lumps many groups together – that the term is not limited to South Asian groups such as Indian and Pakistani, but also includes East Asian groups. Similarly, an immigrant Nepalese man described how “Asian” often means Chinese for many Americans. A Filipino woman summed it up this way:

“Now I consider myself to be both Filipino and Asian American, but growing up in [Southern California] … I didn’t start to identify as Asian American until college because in [the Los Angeles suburb where I lived], it’s a big mix of everything – Black, Latino, Pacific Islander and Asian … when I would go into spaces where there were a lot of other Asians, especially East Asians, I didn’t feel like I belonged. … In media, right, like people still associate Asian with being East Asian.”

–U.S.-born woman of Filipino origin in mid-20s

Participants also noted they have encountered confusion or the tendency for others to view Asian Americans as people from mostly East Asian countries, such as China, Japan and Korea. For some, this confusion even extends to interactions with other Asian American groups. A Pakistani man remarked on how he rarely finds Pakistani or Indian brands when he visits Asian stores. Instead, he recalled mostly finding Vietnamese, Korean and Chinese items.

Among participants of South Asian descent, some identified with the label “South Asian” more than just “Asian.” There were other nuances, too, when it comes to the labels people choose. Some Indian participants, for example, said people sometimes group them with Native Americans who are also referred to as Indians in the United States. This Indian woman shared her experience at school:

“I love South Asian or ‘Desi’ only because up until recently … it’s fairly new to say South Asian. I’ve always said ‘Desi’ because growing up … I’ve had to say I’m the red dot Indian, not the feather Indian. So annoying, you know? … Always a distinction that I’ve had to make.”

–U.S.-born woman of Indian origin in late 20s

Participants with multiethnic or multiracial backgrounds described their own unique experiences with their identity. Rather than choosing one racial or ethnic group over the other, some participants described identifying with both groups, since this more accurately describes how they see themselves. In some cases, this choice reflected the history of the Asian diaspora. For example, an immigrant Cambodian man described being both Khmer/Cambodian and Chinese, since his grandparents came from China. Some other participants recalled going through an “identity crisis” as they navigated between multiple identities. As one woman explained:

“I would say I went through an identity crisis. … It’s because of being multicultural. … There’s also French in the mix within my family, too. Because I don’t identify, speak or understand the language, I really can’t connect to the French roots … I’m in between like Cambodian and Thai, and then Chinese and then French … I finally lumped it up. I’m just an Asian American and proud of all my roots.”

–U.S.-born woman of Cambodian origin in mid-30s

In other cases, the choice reflected U.S. patterns of intermarriage. Asian newlyweds have the highest intermarriage rate of any racial or ethnic group in the country. One Japanese-origin man with Hispanic roots noted:

“So I would like to see myself as a Hispanic Asian American. I want to say Hispanic first because I have more of my mom’s culture in me than my dad’s culture. In fact, I actually have more American culture than my dad’s culture for what I do normally. So I guess, Hispanic American Asian.”

–U.S.-born man of Hispanic and Japanese origin in early 40s

Other identities beyond race or ethnicity are also important

Focus group participants also talked about their identity beyond the racial or ethnic dimension. For example, one Chinese woman noted that the best term to describe her would be “immigrant.” Faith and religious ties were also important to some. One immigrant participant talked about his love of Pakistani values and how religion is intermingled into Pakistani culture. Another woman explained:

“[Japanese language and culture] are very important to me and ingrained in me because they were always part of my life, and I felt them when I was growing up. Even the word itadakimasu reflects Japanese culture or the tradition. Shinto religion is a part of the culture. They are part of my identity, and they are very important to me.”

–Immigrant woman of Japanese origin in mid-30s

For some, gender is another important aspect of identity. One Korean participant emphasized that being a woman is an important part of her identity. For others, sexual orientation is an essential part of their overall identity. One U.S.-born Filipino participant described herself as “queer Asian American.” Another participant put it this way:

“I belong to the [LGBTQ] community … before, what we only know is gay and lesbian. We don’t know about being queer, nonbinary. [Here], my horizon of knowing what genders and gender roles is also expanded … in the Philippines, if you’ll be with same sex, you’re considered gay or lesbian. But here … what’s happening is so broad, on how you identify yourself.”

–Immigrant woman of Filipino origin in early 20s

Immigrant identity is tied to their ethnic heritage

Participants born outside the United States tended to link their identity with their ethnic heritage. Some felt strongly connected with their ethnic ties due to their citizenship status. For others, the lack of permanent residency or citizenship meant they have stronger ties to their ethnicity and birthplace. And in some cases, participants said they held on to their ethnic identity even after they became U.S. citizens. One woman emphasized that she will always be Taiwanese because she was born there, despite now living in the U.S.

For other participants, family origin played a central role in their identity, regardless of their status in the U.S. According to some of them, this attitude was heavily influenced by their memories and experiences in early childhood when they were still living in their countries of origin. These influences are so profound that even after decades of living in the U.S., some still feel the strong connection to their ethnic roots. And those with U.S.-born children talked about sending their kids to special educational programs in the U.S. to learn about their ethnic heritage.

“Yes, as for me, I hold that I am Khmer because our nationality cannot be deleted, our identity is Khmer as I hold that I am Khmer … so I try, even [with] my children today, I try to learn Khmer through Zoom through the so-called Khmer Parent Association.”

–Immigrant man of Cambodian origin in late 50s

Navigating life in America is an adjustment

Many participants pointed to cultural differences they have noticed between their ethnic culture and U.S. culture. One of the most distinct differences is in food. For some participants, their strong attachment to the unique dishes of their families and their countries of origin helps them maintain strong ties to their ethnic identity. One Sri Lankan participant shared that her roots are still in Sri Lanka, since she still follows Sri Lankan traditions in the U.S. such as preparing kiribath (rice with coconut milk) and celebrating Ramadan.

For other participants, interactions in social settings with those outside their own ethnic group circles highlighted cultural differences. One Bangladeshi woman talked about how Bengalis share personal stories and challenges with each other, while others in the U.S. like to have “small talk” about TV series or clothes.

Many immigrants in the focus groups have found it is easier to socialize when they are around others belonging to their ethnicity. When interacting with others who don’t share the same ethnicity, participants noted they must be more self-aware about cultural differences to avoid making mistakes in social interactions. Here, participants described the importance of learning to “fit in,” to avoid feeling left out or excluded. One Korean woman said:

“Every time I go to a party, I feel unwelcome. … In Korea, when I invite guests to my house and one person sits without talking, I come over and talk and treat them as a host. But in the United States, I have to go and mingle. I hate mingling so much. I have to talk and keep going through unimportant stories. In Korea, I am assigned to a dinner or gathering. I have a party with a sense of security. In America, I have nowhere to sit, and I don’t know where to go and who to talk to.”

–Immigrant woman of Korean origin in mid-40s

And a Bhutanese immigrant explained:

“In my case, I am not an American. I consider myself a Bhutanese. … I am a Bhutanese because I do not know American culture to consider myself as an American. It is very difficult to understand the sense of humor in America. So, we are pure Bhutanese in America.”

–Immigrant man of Bhutanese origin in early 40s

Language was also a key aspect of identity for the participants. Many immigrants in the focus groups said they speak a language other than English at home and in their daily lives. One Vietnamese man considered himself Vietnamese since his Vietnamese is better than his English. Others emphasized their English skills. A Bangladeshi participant felt that she was more accepted in the workplace when she does more “American” things and speaks fluent English, rather than sharing things from Bangladeshi culture. She felt that others in her workplace correlate her English fluency with her ability to do her job. For others born in the U.S., the language they speak at home influences their connection to their ethnic roots.

“Now if I go to my work and do show my Bengali culture and Asian culture, they are not going to take anything out of it. So, basically, I have to show something that they are interested in. I have to show that I am American, [that] I can speak English fluently. I can do whatever you give me as a responsibility. So, in those cases I can’t show anything about my culture.”

–Immigrant woman of Bangladeshi origin in late 20s

“Being bi-ethnic and tri-cultural creates so many unique dynamics, and … one of the dynamics has to do with … what it is to be Americanized. … One of the things that played a role into how I associate the identity is language. Now, my father never spoke Spanish to me … because he wanted me to develop a fluency in English, because for him, he struggled with English. What happened was three out of the four people that raised me were Khmer … they spoke to me in Khmer. We’d eat breakfast, lunch and dinner speaking Khmer. We’d go to the temple in Khmer with the language and we’d also watch videos and movies in Khmer. … Looking into why I strongly identify with the heritage, one of the reasons is [that] speaking that language connects to the home I used to have [as my families have passed away].”

–U.S.-born man of Cambodian origin in early 30s

Balancing between individualistic and collective thinking

For some immigrant participants, the main differences between themselves and others who are seen as “truly American” were less about cultural differences, or how people behave, and more about differences in “mindset,” or how people think. Those who identified strongly with their ethnicity discussed how their way of thinking is different from a “typical American.” To some, the “American mentality” is more individualistic, with less judgment on what one should do or how they should act. One immigrant Japanese man, for example, talked about how other Japanese-origin co-workers in the U.S. would work without taking breaks because it’s culturally inconsiderate to take a break while others continued working. However, he would speak up for himself and other workers when they are not taking any work breaks. He attributed this to his “American” way of thinking, which encourages people to stand up for themselves.

Some U.S.-born participants who grew up in an immigrant family described the cultural clashes that happened between themselves and their immigrant parents. Participants talked about how the second generation (children of immigrant parents) struggles to pursue their own dreams while still living up to the traditional expectations of their immigrant parents.

“I feel like one of the biggest things I’ve seen, just like [my] Asian American friends overall, is the kind of family-individualistic clash … like wanting to do your own thing is like, is kind of instilled in you as an American, like go and … follow your dream. But then you just grow up with such a sense of like also wanting to be there for your family and to live up to those expectations, and I feel like that’s something that’s very pronounced in Asian cultures.”

–U.S.-born man of Indian origin in mid-20s

Discussions also highlighted differences about gender roles between growing up in America compared with elsewhere.

“As a woman or being a girl, because of your gender, you have to keep your mouth shut [and] wait so that they call on you for you to speak up. … I do respect our elders and I do respect hearing their guidance but I also want them to learn to hear from the younger person … because we have things to share that they might not know and that [are] important … so I like to challenge gender roles or traditional roles because it is something that [because] I was born and raised here [in America], I learn that we all have the equal rights to be able to speak and share our thoughts and ideas.”

–U.S.-born woman of Cambodian origin in mid-30s

U.S. born have mixed ties to their family’s heritage

“I think being Hmong is somewhat of being free, but being free of others’ perceptions of you or of others’ attempts to assimilate you or attempts to put pressure on you. I feel like being Hmong is to resist, really.”

Pa Houa, documentary participant

How U.S.-born participants identify themselves depends on their familiarity with their own heritage, whom they are talking with, where they are when asked about their identity and what the answer is used for. Some mentioned that they have stronger ethnic ties because they are very familiar with their family’s ethnic heritage. Others talked about how their eating habits and preferred dishes made them feel closer to their ethnic identity. For example, one Korean participant shared his journey of getting closer to his Korean heritage because of Korean food and customs. When some participants shared their reasons for feeling closer to their ethnic identity, they also expressed a strong sense of pride with their unique cultural and ethnic heritage.

“I definitely consider myself Japanese American. I mean I’m Japanese and American. Really, ever since I’ve grown up, I’ve really admired Japanese culture. I grew up watching a lot of anime and Japanese black and white films. Just learning about [it], I would hear about Japanese stuff from my grandparents … myself, and my family having blended Japanese culture and American culture together.”

–U.S.-born man of Japanese origin in late 20s

Meanwhile, participants who were not familiar with their family’s heritage showed less connection with their ethnic ties. One U.S.-born woman said she has a hard time calling herself Cambodian, as she is “not close to the Cambodian community.” Participants with stronger ethnic ties talked about relating to their specific ethnic group more than the broader Asian group. Another woman noted that being Vietnamese is “more specific and unique than just being Asian” and said that she didn’t feel she belonged with other Asians. Some participants also disliked being seen as or called “Asian,” in part because they want to distinguish themselves from other Asian groups. For example, one Taiwanese woman introduces herself as Taiwanese when she can, because she had frequently been seen as Chinese.

Some in the focus groups described how their views of their own identities shifted as they grew older. For example, some U.S.-born and immigrant participants who came to the U.S. at younger ages described how their experiences in high school and the need to “fit in” were important in shaping their own identities. A Chinese woman put it this way:

“So basically, all I know is that I was born in the United States. Again, when I came back, I didn’t feel any barrier with my other friends who are White or Black. … Then I got a little confused in high school when I had trouble self-identifying if I am Asian, Chinese American, like who am I. … Should I completely immerse myself in the American culture? Should I also keep my Chinese identity and stuff like that? So yeah, that was like the middle of that mist. Now, I’m pretty clear about myself. I think I am Chinese American, Asian American, whatever people want.”

–U.S.-born woman of Chinese origin in early 20s

Identity is influenced by birthplace

“I identified myself first and foremost as American. Even on the forms that you fill out that says, you know, ‘Asian’ or ‘Chinese’ or ‘other,’ I would check the ‘other’ box, and I would put ‘American Chinese’ instead of ‘Chinese American.’”

Brent, documentary participant

When talking about what it means to be “American,” participants offered their own definitions. For some, “American” is associated with acquiring a distinct identity alongside their ethnic or racial backgrounds, rather than replacing them. One Indian participant put it this way:

“I would also say [that I am] Indian American just because I find myself always bouncing between the two … it’s not even like dual identity, it just is one whole identity for me, like there’s not this separation. … I’m doing [both] Indian things [and] American things. … They use that term like ABCD … ‘American Born Confused Desi’ … I don’t feel that way anymore, although there are those moments … but I would say [that I am] Indian American for sure.”

–U.S.-born woman of Indian origin in early 30s

Meanwhile, some U.S.-born participants view being American as central to their identity while also valuing the culture of their family’s heritage.

Many immigrant participants associated the term “American” with immigration status or citizenship. One Taiwanese woman said she can’t call herself American since she doesn’t have a U.S. passport. Notably, U.S. citizenship is an important milestone for many immigrant participants, giving them a stronger sense of belonging and ultimately calling themselves American. A Bangladeshi participant shared that she hasn’t received U.S. citizenship yet, and she would call herself American after she receives her U.S. passport.

Other participants gave an even narrower definition, saying only those born and raised in the United States are truly American. One Taiwanese woman mentioned that her son would be American since he was born, raised and educated in the U.S. She added that while she has U.S. citizenship, she didn’t consider herself American since she didn’t grow up in the U.S. This narrower definition has implications for belonging. Some immigrants in the groups said they could never become truly American since the way they express themselves is so different from those who were born and raised in the U.S. A Japanese woman pointed out that Japanese people “are still very intimidated by authorities,” while those born and raised in America give their opinions without hesitation.

“As soon as I arrived, I called myself a Burmese immigrant. I had a green card, but I still wasn’t an American citizen. … Now I have become a U.S. citizen, so now I am a Burmese American.”

–Immigrant man of Burmese origin in mid-30s

“Since I was born … and raised here, I kind of always view myself as American first who just happened to be Asian or Chinese. So I actually don’t like the term Chinese American or Asian American. I’m American Asian or American Chinese. I view myself as American first.”

–U.S.-born man of Chinese origin in early 60s

“[I used to think of myself as] Filipino, but recently I started saying ‘Filipino American’ because I got [U.S.] citizenship. And it just sounds weird to say Filipino American, but I’m trying to … I want to accept it. I feel like it’s now marry-able to my identity.”

–Immigrant woman of Filipino origin in early 30s

For others, American identity is about the process of ‘becoming’ culturally American

Immigrant participants also emphasized how their experiences and time living in America inform their views of being an “American.” As a result, some started to see themselves as Americans after spending more than a decade in the U.S. One Taiwanese man considered himself an American since he knows more about the U.S. than Taiwan after living in the U.S. for over 52 years.

But for other immigrant participants, the process of “becoming” American is not about how long they have lived in the U.S., but rather how familiar they are with American culture and their ability to speak English with little to no accent. This is especially true for those whose first language is not English, as learning and speaking it without an accent can be a big challenge for some. One Bangladeshi participant shared that his pronunciation of “hot water” was very different from American English, resulting in confusions in communication. By contrast, those who were more confident in their English skills felt they can better understand American culture and values as a result, leading them to a stronger connection with an American identity.

“[My friends and family tease me for being Americanized when I go back to Japan.] I think I seem a little different to people who live in Japan. I don’t think they mean anything bad, and they [were] just joking, because I already know that I seem a little different to people who live in Japan.”

–Immigrant man of Japanese origin in mid-40s

“I value my Hmong culture, and language, and ethnicity, but I also do acknowledge, again, that I was born here in America and I’m grateful that I was born here, and I was given opportunities that my parents weren’t given opportunities for.”

–U.S.-born woman of Hmong origin in early 30s

This is how others see and treat me

During the focus group discussions about identity, a recurring theme emerged about the difference between how participants saw themselves and how others see them. When asked to elaborate on their experiences and their points of view, some participants shared experiences they had with people misidentifying their race or ethnicity. Others talked about their frustration with being labeled the “model minority.” In all these discussions, participants shed light on the negative impacts that mistaken assumptions and labels had on their lives.

All people see is ‘Asian’

For many, interactions with others (non-Asians and Asians alike) often required explaining their backgrounds, reacting to stereotypes, and for those from smaller origin groups in particular, correcting the misconception that being “Asian” means you come from one of the larger Asian ethnic groups. Several participants remarked that in their own experiences, when others think about Asians, they tend to think of someone who is Chinese. As one immigrant Filipino woman put it, “Interacting with [non-Asians in the U.S.], it’s hard. … Well, first, I look Spanish. I mean, I don’t look Asian, so would you guess – it’s like they have a vision of what an Asian [should] look like.” Similarly, an immigrant Indonesian man remarked how Americans tended to see Asians primarily through their physical features, which not all Asian groups share.

Several participants also described how the tendency to view Asians as a monolithic group can be even more common in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The first [thing people think of me as] is just Chinese. ‘You guys are just Chinese.’ I’m not the only one who felt [this] after the COVID-19 outbreak. ‘Whether you’re Japanese, Korean, or Southeast Asian, you’re just Chinese [to Americans]. I should avoid you.’ I’ve felt this way before, but I think I’ve felt it a bit more after the COVID-19 outbreak.”

–Immigrant woman of Korean origin in early 30s

At the same time, other participants described their own experiences trying to convince others that they are Asian or Asian American. This was a common experience among Southeast Asian participants.

“I have to convince people I’m Asian, not Middle Eastern. … If you type in Asian or you say Asian, most people associate it with Chinese food, Japanese food, karate, and like all these things but then they don’t associate it with you.”

–U.S.-born man of Pakistani origin in early 30s

The model minority myth and its impact

“I’ve never really done the best academically, compared to all my other Asian peers too. I never really excelled. I wasn’t in honors. … Those stereotypes, I think really [have] taken a toll on my self-esteem.”

Diane, documentary participant

Across focus groups, immigrant and U.S.-born participants described the challenges of the seemingly positive stereotypes of Asians as intelligent, gifted in technical roles and hardworking. Participants often referred to this as the “model minority myth.”

The label “model minority” was coined in the 1960s and has been used to characterize Asian Americans as financially and educationally successful and hardworking when compared with other groups. However, for many Asians living in the United States, these characterizations do not align with their lived experiences or reflect their socioeconomic backgrounds. Indeed, among Asian origin groups in the U.S., there are wide differences in economic and social experiences.

Academic research on the model minority myth has pointed to its impact beyond Asian Americans and towards other racial and ethnic groups, especially Black Americans, in the U.S. Some argue that the model minority myth has been used to justify policies that overlook the historical circumstances and impacts of colonialism, slavery, discrimination and segregation on other non-White racial and ethnic groups.

Many participants noted ways in which the model minority myth has been harmful. For some, expectations based on the myth didn’t match their own experiences of coming from impoverished communities. Some also recalled experiences at school when they struggled to meet their teachers’ expectations in math and science.

“As an Asian person, I feel like there’s that stereotype that Asian students are high achievers academically. They’re good at math and science. … I was a pretty mediocre student, and math and science were actually my weakest subjects, so I feel like it’s either way you lose. Teachers expect you to fit a certain stereotype and if you’re not, then you’re a disappointment, but at the same time, even if you are good at math and science, that just means that you’re fitting a stereotype. It’s [actually] your own achievement, but your teachers might think, ‘Oh, it’s because they’re Asian,’ and that diminishes your achievement.”

–U.S.-born woman of Korean origin in late 20s

Some participants felt that even when being Asian worked in their favor in the job market, they encountered stereotypes that “Asians can do quality work with less compensation” or that “Asians would not complain about anything at work.”

“There is a joke from foreigners and even Asian Americans that says, ‘No matter what you do, Asians always do the best.’ You need to get A, not just B-plus. Otherwise, you’ll be a disgrace to the family. … Even Silicon Valley hires Asian because [an] Asian’s wage is cheaper but [they] can work better. When [work] visa overflow happens, they hire Asians like Chinese and Indian to work in IT fields because we are good at this and do not complain about anything.”

–Immigrant man of Thai origin in early 40s

Others expressed frustration that people were placing them in the model minority box. One Indian woman put it this way:

“Indian people and Asian people, like … our parents or grandparents are the ones who immigrated here … against all odds. … A lot of Indian and Asian people have succeeded and have done really well for themselves because they’ve worked themselves to the bone. So now the expectations [of] the newer generations who were born here are incredibly unrealistic and high. And you get that not only from your family and the Indian community, but you’re also getting it from all of the American people around you, expecting you to be … insanely good at math, play an instrument, you know how to do this, you know how to do that, but it’s not true. And it’s just living with those expectations, it’s difficult.”

–U.S.-born woman of Indian origin in early 20s

Whether U.S. born or immigrants, Asians are often seen by others as foreigners

“Being only not quite 10 years old, it was kind of exciting to ride on a bus to go someplace. But when we went to Pomona, the assembly center, we were stuck in one of the stalls they used for the animals.”

Tokiko, documentary participant

Across all focus groups, participants highlighted a common question they are asked in America when meeting people for the first time: “Where are you really from?” For participants, this question implied that people think they are “foreigners,” even though they may be longtime residents or citizens of the United States or were born in the country. One man of Vietnamese origin shared his experience with strangers who assumed that he and his friends are North Korean. Perhaps even more hurtful, participants mentioned that this meant people had a preconceived notion of what an “American” is supposed to look like, sound like or act like. One Chinese woman said that White Americans treated people like herself as outsiders based on her skin color and appearance, even though she was raised in the U.S.

Many focus group participants also acknowledged the common stereotype of treating Asians as “forever foreigners.” Some immigrant participants said they felt exhausted from constantly being asked this question by people even when they speak perfect English with no accent. During the discussion, a Korean immigrant man recalled that someone had said to him, “You speak English well, but where are you from?” One Filipino participant shared her experience during the first six months in the U.S.:

“You know, I spoke English fine. But there were certain things that, you know, people constantly questioning you like, oh, where are you from? When did you come here? You know, just asking about your experience to the point where … you become fed up with it after a while.”

–Immigrant woman of Filipino origin in mid-30s

U.S.-born participants also talked about experiences when others asked where they are from. Many shared that they would not talk about their ethnic origin right away when answering such a question because it often led to misunderstandings and assumptions that they are immigrants.

“I always get that question of, you know, ‘Where are you from?’ and I’m like, ‘I’m from America.’ And then they’re like, ‘No. Where are you from-from?’ and I’m like, ‘Yeah, my family is from Pakistan,’ so it’s like I always had like that dual identity even though it’s never attached to me because I am like, of Pakistani descent.”

–U.S.-born man of Pakistani origin in early 20s

One Korean woman born in the U.S. said that once people know she is Korean, they ask even more offensive questions such as “Are you from North or South Korea?” or “Do you still eat dogs?”

In a similar situation, this U.S.-born Indian woman shared her responses:

“I find that there’s a, ‘So but where are you from?’ Like even in professional settings when they feel comfortable enough to ask you. ‘So – so where are you from?’ ‘Oh, I was born in [names city], Colorado. Like at [the hospital], down the street.’ ‘No, but like where are you from?’ ‘My mother’s womb?’”

–U.S.-born woman of Indian origin in early 40s

Ignorance and misinformation about Asian identity can lead to contentious encounters

“I have dealt with kids who just gave up on their Sikh identity, cut their hair and groomed their beard and everything. They just wanted to fit in and not have to deal with it, especially [those] who are victim or bullied in any incident.”

Surinder, documentary participant

In some cases, ignorance and misinformation about Asians in the U.S. lead to inappropriate comments or questions and uncomfortable or dangerous situations. Participants shared their frustration when others asked about their country of origin, and they then had to explain their identity or correct misunderstandings or stereotypes about their background. At other times, some participants faced ignorant comments about their ethnicity, which sometimes led to more contentious encounters. For example, some Indian or Pakistani participants talked about the attacks or verbal abuse they experienced from others blaming them for the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Others discussed the racial slurs directed toward them since the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Some Japanese participants recalled their families losing everything and being incarcerated during World War II and the long-term effect it had on their lives.

“I think like right now with the coronavirus, I think we’re just Chinese, Chinese American, well, just Asian American or Asians in general, you’re just going through the same struggles right now. Like everyone is just blaming whoever looks Asian about the virus. You don’t feel safe.”

–U.S.-born man of Chinese origin in early 30s

“At the beginning of the pandemic, a friend and I went to celebrate her birthday at a club and like these guys just kept calling us COVID.”

–U.S.-born woman of Korean origin in early 20s

“There [were] a lot of instances after 9/11. One day, somebody put a poster about 9/11 [in front of] my business. He was wearing a gun. … On the poster, it was written ‘you Arabs, go back to your country.’ And then someone came inside. He pointed his gun at me and said ‘Go back to your country.’”

–Immigrant man of Pakistani origin in mid-60s

“[My parents went through the] internment camps during World War II. And my dad, he was in high school, so he was – they were building the camps and then he was put into the Santa Anita horse track place, the stables there. And then they were sent – all the Japanese Americans were sent to different camps, right, during World War II and – in California. Yeah, and they lost everything, yeah.”

–U.S.-born woman of Japanese origin in mid-60s

This is what it means to be home in America

As focus group participants contemplated their identity during the discussions, many talked about their sense of belonging in America. Although some felt frustrated with people misunderstanding their ethnic heritage, they didn’t take a negative view of life in America. Instead, many participants – both immigrant and U.S. born – took pride in their unique cultural and ethnic backgrounds. In these discussions, people gave their own definitions of America as a place with a diverse set of cultures, with their ethnic heritage being a part of it.

Taking pride in their unique cultures

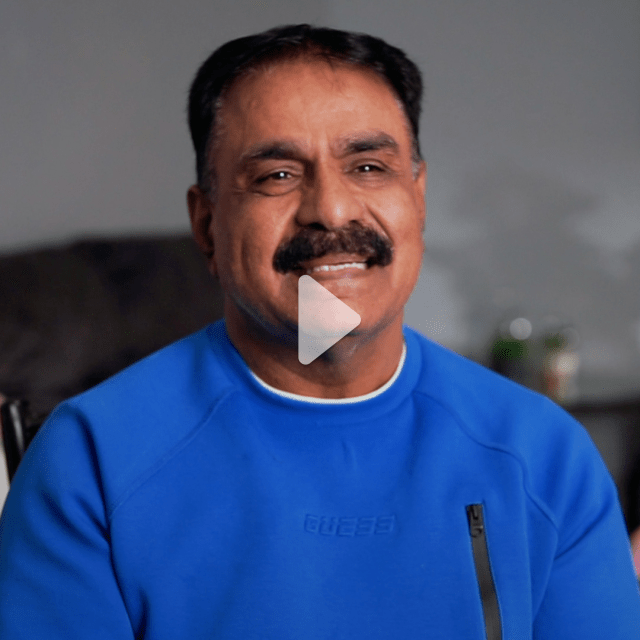

“Being a Pakistani American, I’m proud. … Because I work hard, and I make true my dreams from here.”

Shahid, documentary participant

Despite the challenges of adapting to life in America for immigrant participants or of navigating their dual cultural identity for U.S.-born ones, focus group participants called America their home. And while participants talked about their identities in different ways – ethnic identity, racial (Asian) identity, and being American – they take pride in their unique cultures. Many also expressed a strong sense of responsibility to give back or support their community, sharing their cultural heritage with others on their own terms.

“Right now it has been a little difficult. I think it has been for all Asians because of the COVID issue … but I’m glad that we’re all here [in America]. I think we should be proud to be here. I’m glad that our families have traveled here, and we can help make life better for communities, our families and ourselves. I think that’s really a wonderful thing. We can be those role models for a lot of the future, the younger folks. I hope that something I did in the last years will have impacted either my family, friends or students that I taught in other community things that I’ve done. So you hope that it helps someplace along the line.”

–U.S.-born woman of Japanese origin in mid-60s

“I am very proud of my culture. … There is not a single Bengali at my workplace, but people know the name of my country. Maybe many years [later] – educated people know all about the country. So, I don’t have to explain that there is a small country next to India and Nepal. It’s beyond saying. People after all know Bangladesh. And there are so many Bengali present here as well. So, I am very proud to be a Bangladeshi.”

–Immigrant woman of Bangladeshi origin in late 20s

Where home is

When asked about the definition of home, some immigrant participants said home is where their families are located. Immigrants in the focus groups came to the United States by various paths, whether through work opportunities, reuniting with family or seeking a safe haven as refugees. Along their journey, some received support from family members, their local community or other individuals, while others overcame challenges by themselves. Either way, they take pride in establishing their home in America and can feel hurt when someone tells them to “go back to your country.” In response, one Laotian woman in her mid-40s said, “This is my home. My country. Go away.”

“If you ask me personally, I view my home as my house … then I would say my house is with my family because wherever I go, I cannot marry if I do not have my family so that is how I would answer.”

–Immigrant man of Hmong origin in late 30s

“[If somebody yelled at me ‘go back to your country’] I’d feel angry because this is my country! I live here. America is my country. I grew up here and worked here … I’d say, ‘This is my country! You go back to your country! … I will not go anywhere. This is my home. I will live here.’ That’s what I’d say.”

–Immigrant woman of Laotian origin in early 50s

‘American’ means to blend their unique cultural and ethnic heritage with that in the U.S.

“I want to teach my children two traditions – one American and one Vietnamese – so they can compare and choose for themselves the best route in life.”

Helen, documentary participant

(translated from Vietnamese)

Both U.S.-born and immigrant participants in the focus groups shared their experiences of navigating a dual cultural environment between their ethnic heritage and American culture. A common thread that emerged was that being Asian in America is a process of blending two or more identities as one.

“Yeah, I want to say that’s how I feel – because like thinking about it, I would call my dad Lao but I would call myself Laotian American because I think I’m a little more integrated in the American society and I’ve also been a little more Americanized, compared to my dad. So that’s how I would see it.”

–U.S.-born man of Laotian origin in late 20s

“I mean, Bangladeshi Americans who are here, we are carrying Bangladeshi culture, religion, food. I am also trying to be Americanized like the Americans. Regarding language, eating habits.”

–Immigrant man of Bangladeshi origin in mid-50s

“Just like there is Chinese American, Mexican American, Japanese American, Italian American, so there is Indian American. I don’t want to give up Indianness. I am American by nationality, but I am Indian by birth. So whenever I talk, I try to show both the flags as well, both Indian and American flags. Just because you make new relatives but don’t forget the old relatives.”

–Immigrant man of Indian origin in late 40s

About this project

Pew Research Center designed these focus groups to better understand how members of an ethnically diverse Asian population think about their place in America and life here. By including participants of different languages, immigration or refugee experiences, educational backgrounds, and income levels, this focus group study aimed to capture in people’s own words what it means to be Asian in America. The discussions in these groups may or may not resonate with all Asians living in the United States. Browse excerpts from our focus groups with the interactive quote sorter below, view a video documentary focused on the topics discussed in the focus groups, or tell us your story of belonging in America via social media. The focus group project is part of a broader research project studying the diverse experiences of Asians living in the U.S.

Read sortable quotes from our focus groups

Browse excerpts in the interactive quote sorter from focus group participants in response to the question “What does it mean to be [Vietnamese, Thai, Sri Lankan, Hmong, etc.] like yourself in America?” This interactive allows you to sort quotes from focus group participants by ethnic origin, nativity (U.S. born or born in another country), gender and age.

Video documentary

Videos throughout the data essay illustrate what focus group participants discussed. Those recorded in these videos did not participate in the focus groups but were sampled to have similar demographic characteristics and thematically relevant stories.

Watch the full video documentary and watch additional shorter video clips related to the themes of this data essay.

Share the story of your family and your identity

Did the voices in this data essay resonate? Share your story of what it means to be Asian in America with @pewresearch.

Tell us your story by using the hashtag #BeingAsianInAmerica and @pewidentity on Twitter, as well as #BeingAsianInAmerica and @pewresearch on Instagram.

Methodological note

This cross-ethnic, comparative qualitative research project explores the identity, economic mobility, representation, and experiences of immigration and discrimination among the Asian population in the United States. The analysis is based on 66 focus groups we conducted virtually in the fall of 2021 and included 264 participants from across the U.S. More information about the groups and analysis can be found in this appendix.

Acknowledgments

Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. This data essay was funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the Henry Luce Foundation; The Wallace H. Coulter Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Long Family Foundation; Lu-Hebert Fund; Gee Family Foundation; Joseph Cotchett; the Julian Abdey and Sabrina Moyle Charitable Fund; and Nanci Nishimura.

The accompanying video clips and video documentary were made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from The Sobrato Family Foundation and The Long Family Foundation.

We would also like to thank the Leaders Forum for its thought leadership and valuable assistance in helping make this study possible. This is a collaborative effort based on the input and analysis of a number of individuals and experts at Pew Research Center and outside experts.