People face a number of choices in managing their online privacy, and each person approaches these from a different angle.

Some people are tech-savvy and confident in their ability to protect their data. Others are overwhelmed trying to navigate the privacy settings that tech companies make available. And while many are concerned about their privacy, translating that concern into action can be complicated.

No single factor explains the ins and outs of people’s privacy choices. We explored three things that might matter: knowledge about privacy and cybersecurity topics; confidence in their tech skills; and concern about companies’ data collection. Each sheds light on potential reasons why people do what they do online.

Some overall takeaways:

- Knowledge and privacy choices: More privacy knowledge translates into more steps taken to protect data, but also more skepticism about whether those steps are actually useful.

- Confidence and privacy choices: Those who are most confident using digital devices generally trust themselves to make privacy decisions. They’re less overwhelmed than others. And they are more likely to take steps to protect their data.

- Concern and privacy choices: Concern about how companies use one’s data often goes hand in hand with action. But the most concerned tend to be especially overwhelmed, and not everyone who’s concerned takes these steps. Privacy policies are one example of a place where regardless of concern, Americans are largely inattentive.

Identifying the most and least knowledgeable, confident and concerned

In the sections that follow, we explore how privacy actions and feelings vary by six key groups:

- The most versus least knowledgeable about privacy and cybersecurity;

- The most versus least confident using technology; and

- The most versus least concerned about what companies are doing with people’s data.3

The first two concepts relate to digital literacy. This can be defined in many ways but is widely agreed upon as critical in today’s world – including for technical, daunting topics like managing online privacy.4 The third relates to an ongoing debate: Whether the “privacy paradox” exists. We walk through each of these below.

Knowledge

First, we included five questions that were part of a larger series of questions about tech knowledge.

Three of these questions were related to cybersecurity and best practices for “digital hygiene”: identifying the most secure password from a list, knowing that cookies track users’ visits and activity on websites, and being able to identify an example of two-factor authentication.

Two were about privacy regulations: knowing that the U.S. does not have a comprehensive national privacy law and knowing that websites in the U.S. are prohibited from collecting data from children under age 13 without a parent’s consent.

In total:

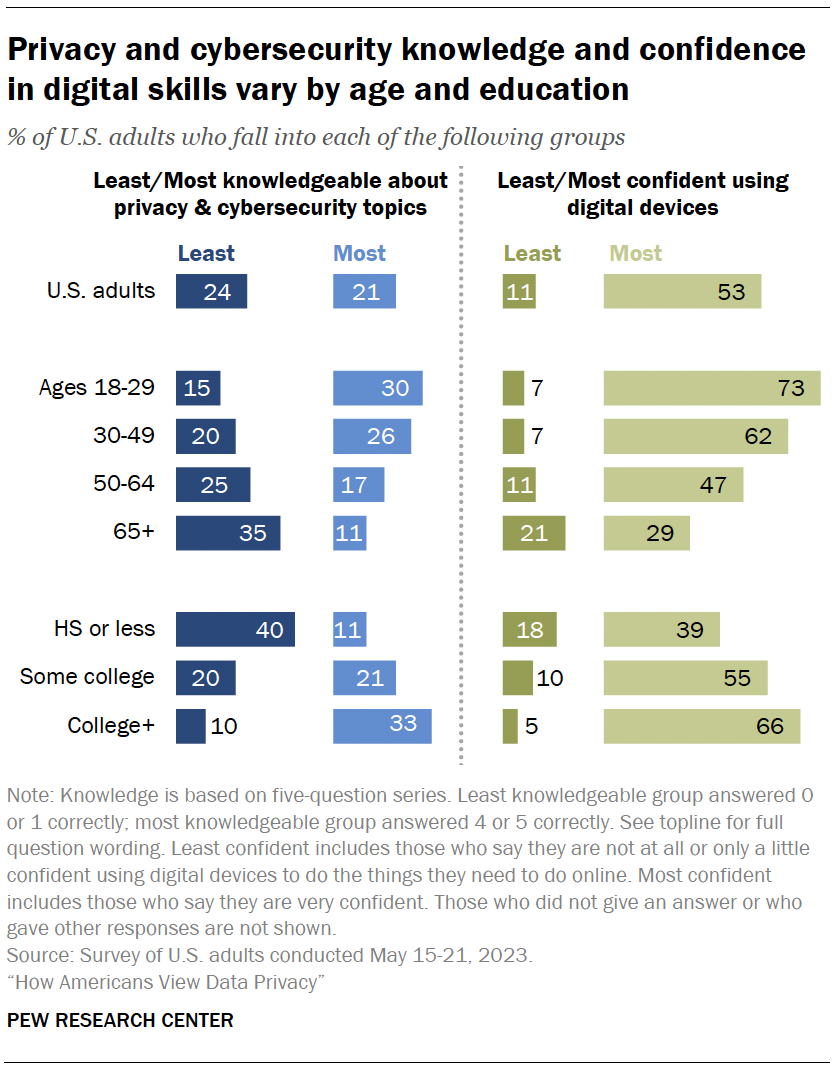

- 21% of Americans can correctly answer at least four of the five items. We refer to this group as most knowledgeable about privacy and cybersecurity topics.5

- 55% give two or three correct answers.

- 24% answer zero or one item correctly; we call this group least knowledgeable.

Levels of knowledge vary notably by age and education.

Confidence

Aside from knowledge, we also explored how people feel about their tech skills.6 Specifically, we asked about people’s confidence using computers, smartphones or other electronic devices to do the things they need to do online.7

- 53% of Americans say they are very confident in these abilities – we refer to them as the most confident.

- 36% are somewhat confident.

- 11% have little to no confidence – the least confident in this report.

And like privacy knowledge, confidence in tech skills varies notably across demographic groups.

Concern

We further looked at people’s concerns about how their data is being used. A large body of research has explored the possibility of a “privacy paradox”: Namely, worry about privacy doesn’t always translate into action.

Whether and why this “paradox” exists are up for debate. Some say convenience wins out even if you have to give up data. Others say people’s behaviors are more about being resigned to the realities of modern digital life.

When it comes to concern:

- 35% of Americans say they are very concerned about how companies are using the data they collect about them. We refer to them as the most concerned about this.

- 46% are somewhat concerned.

- 19% are not at all or not too concerned. We call them the least concerned.

Knowledge and privacy choices

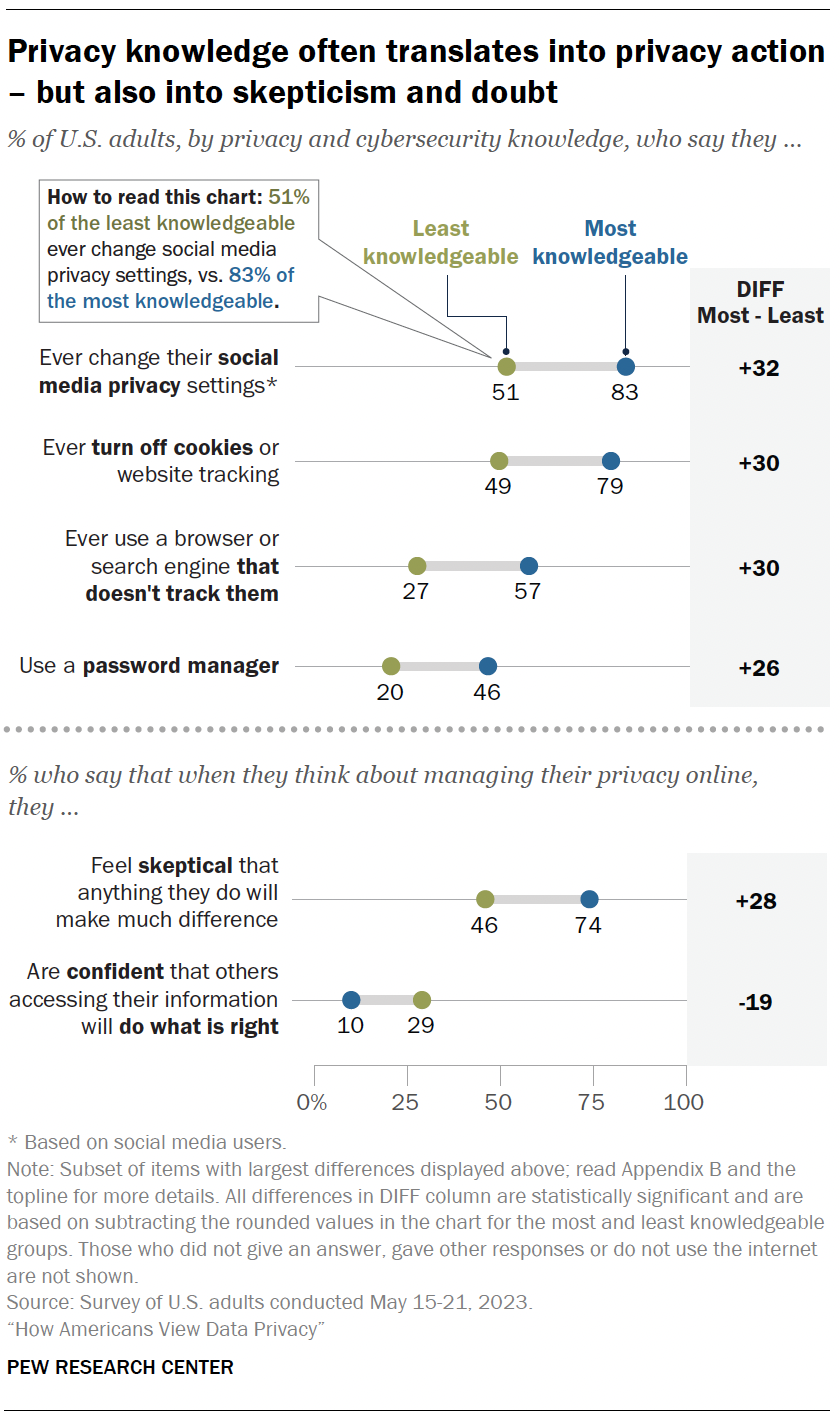

Those who know a great deal about privacy and cybersecurity are consistently more likely than those who know little to take actions to protect their data.8

This pattern shows up across a number of items we examined. Some of the largest differences are in adjusting social media privacy settings, avoiding cookies, using a private browser or search engine and using a password manager.

Yet knowledge breeds doubt as well. The most knowledgeable Americans are far more skeptical than the least knowledgeable that their actions will make a difference. And they are less confident that others who can access their data will do what is right with it.

Age and knowledge

Even among the highly knowledgeable, some digital habits still vary by age.

Among the most knowledgeable social media users:

- 86% of the most knowledgeable users ages 18 to 49 ever change their social media privacy settings.

- This drops to 74% of those 50 and older.

There are also age differences among the most savvy in using password managers:

- Half of highly knowledgeable adults under 50 use a password manager.

- This compares with 40% of those 50 to 64 and 33% of those 65 and up.

Confidence and privacy choices

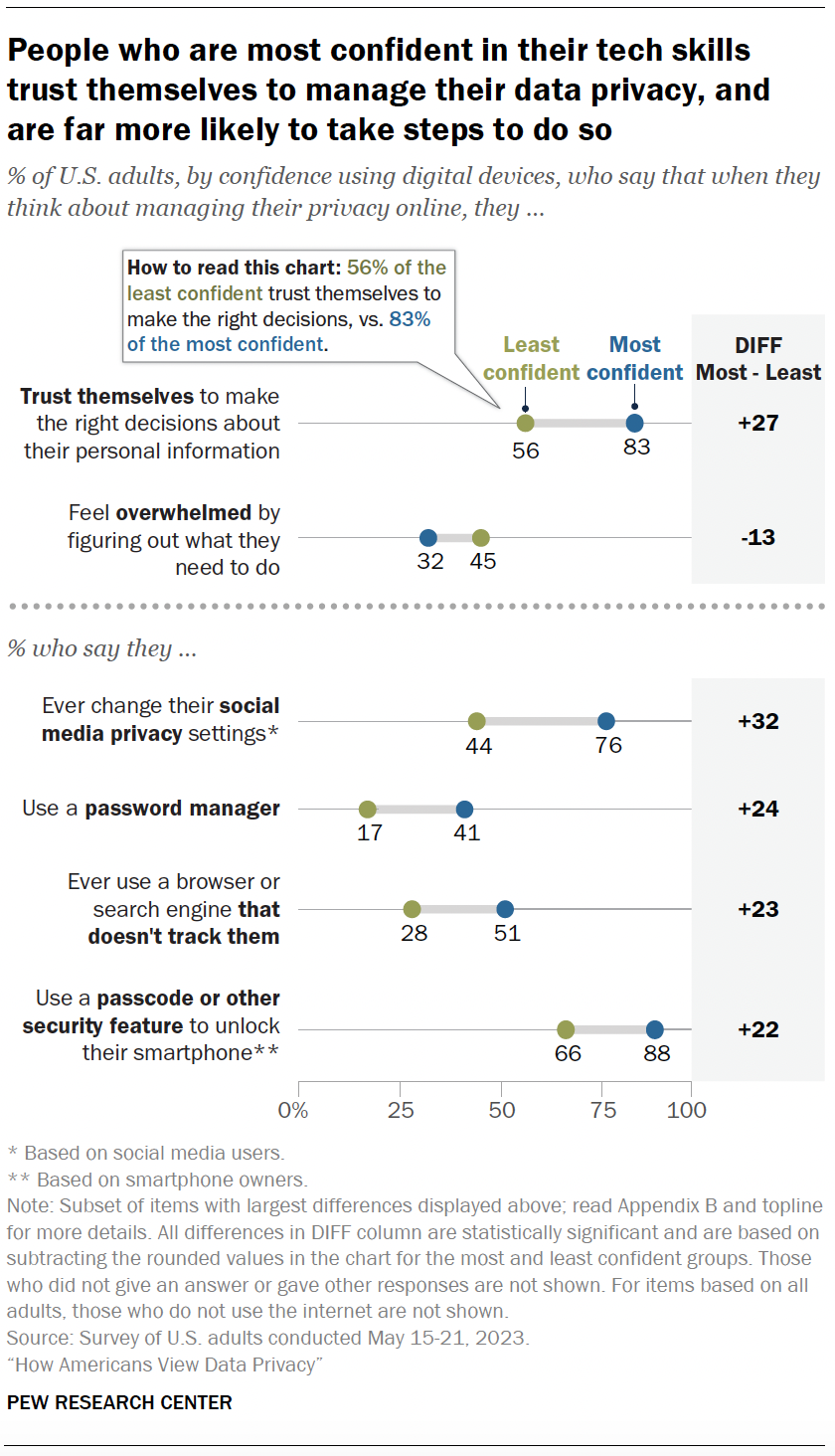

Like knowledge, confidence also relates to how people act and feel about their online privacy.

Americans who are most confident in their tech skills are most likely to trust themselves with privacy decisions. Fully 83% of the most confident say so. Still, more than half – 56% – of the least confident trust themselves with these kinds of calls.

The most confident are also far more likely to ever take each of the actions we explored. For example, 41% of the most confident Americans use a password manager, versus just 17% of those least confident in their tech skills.

The most confident are least likely to be overwhelmed by the task of managing online privacy. Those with moderate or low levels of confidence are both more overwhelmed, by comparison.

Even so, those with little to no confidence take some steps to protect their data:

- 66% of the least confident use a passcode lock on their phone, if they own one.

- 55% of the least confident ever decline cookies or other tracking on websites.

Skepticism also is widespread across confidence levels. A majority of the most confident say they’re skeptical that anything they do will make much difference, and about half of the least confident say the same.

Concern and privacy choices

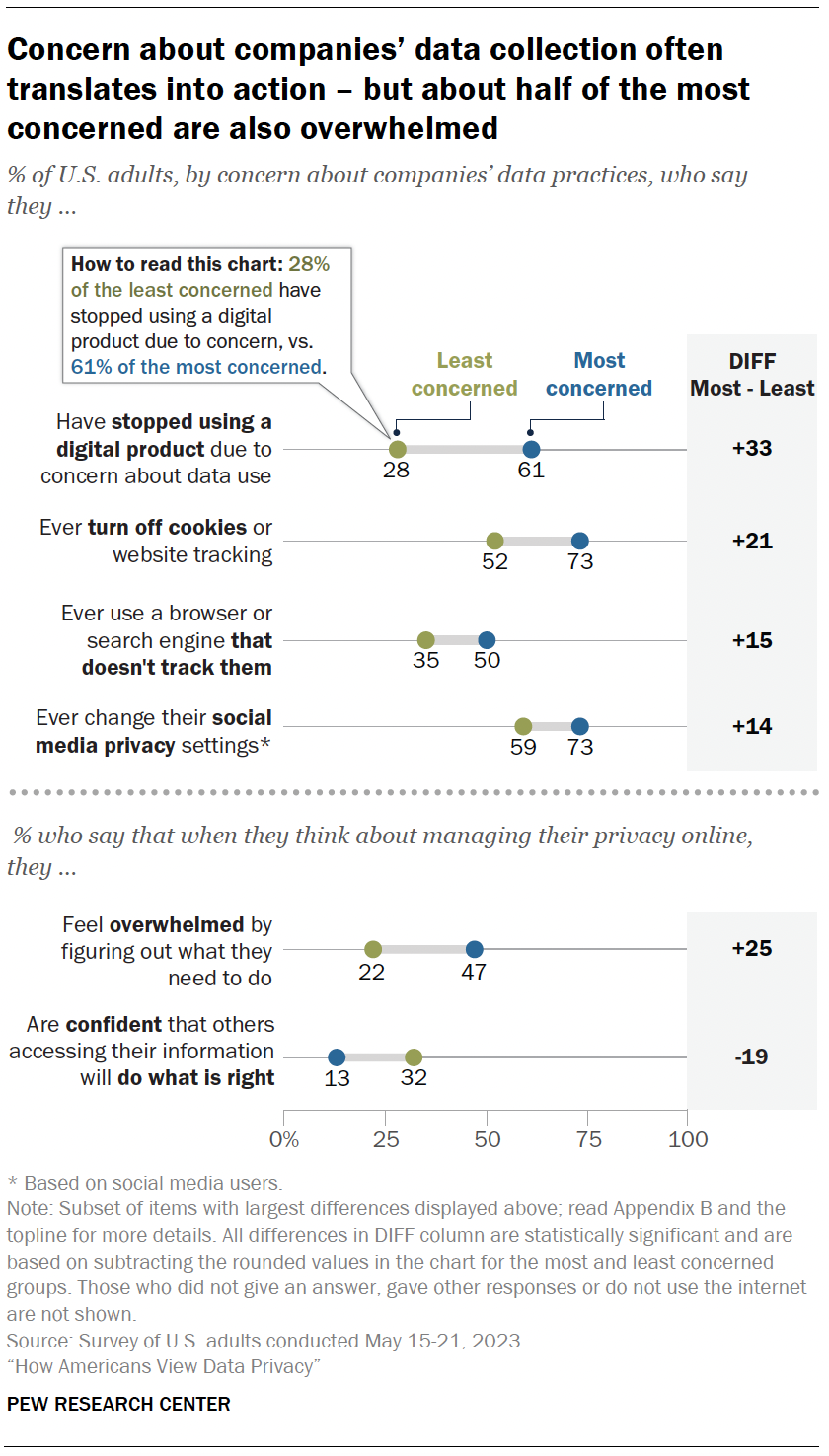

Concern about what companies are doing with people’s data is related to the actions people take to protect their information – but still, not all of these steps are widely adopted.

There are several large differences between the most and the least concerned.

For example, the most concerned are far more likely to have stopped using a digital device, website or app due to worry about how their personal information is being used. They’re also more likely to decline cookies, use a private browser or change social media privacy settings.

Yet this doesn’t mean everyone who is most concerned takes these steps. Half or fewer of the most concerned ever use a browser where they can’t be tracked or use encrypted messaging. And while a majority of the most concerned have changed up the digital products they use because of this, another 34% of this group have not done so.

It can be daunting to figure out how to address privacy concerns, and some of the emotional reactions we explored illustrate this.

The most concerned are far more overwhelmed managing their privacy, compared with those with little to no concern. About half of those who are highly concerned about companies’ data collection say they feel overwhelmed figuring out what to do.

The case of privacy policies

Americans’ approach to privacy policies illustrates these tensions between concern and action.

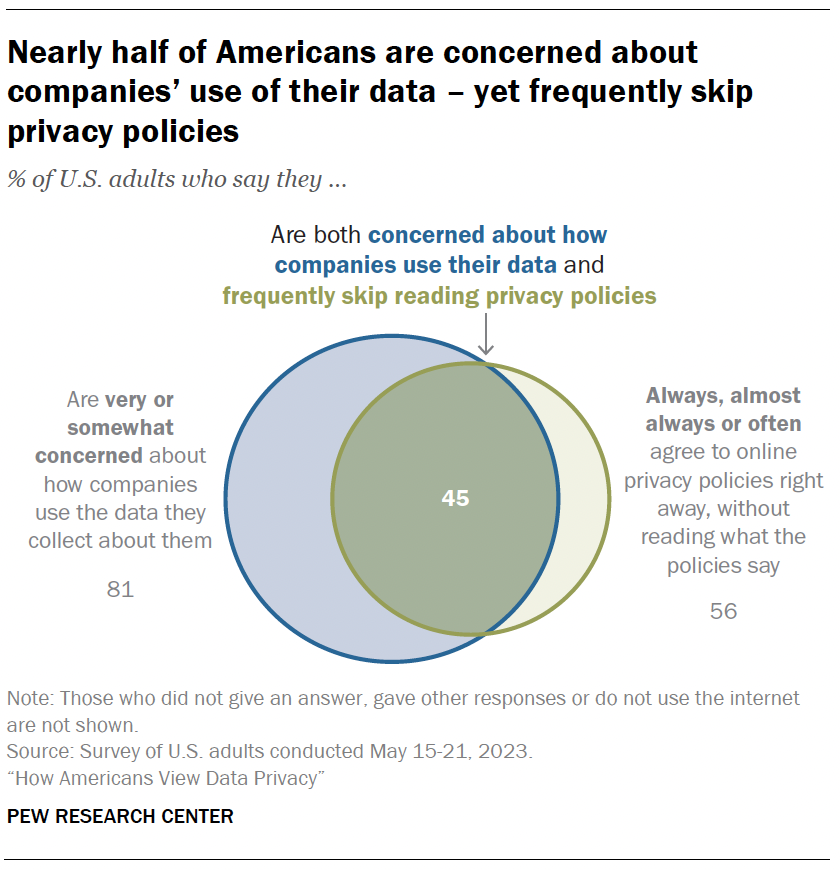

A notable share of Americans – 45% – are very or somewhat concerned about how companies use data they collect about them and, at the same time, say they frequently agree to privacy policies without reading them.

The survey was not designed to explore why people don’t take the time to read these policies despite their concern about what’s being done with their data. But majorities of Americans say they find them ineffective and just something to get past, suggesting that companies’ preferred method of communicating important details isn’t working for many.

How concerned people are is less of a factor here: About half of Americans or more skip privacy policies frequently, regardless of concern about data use.

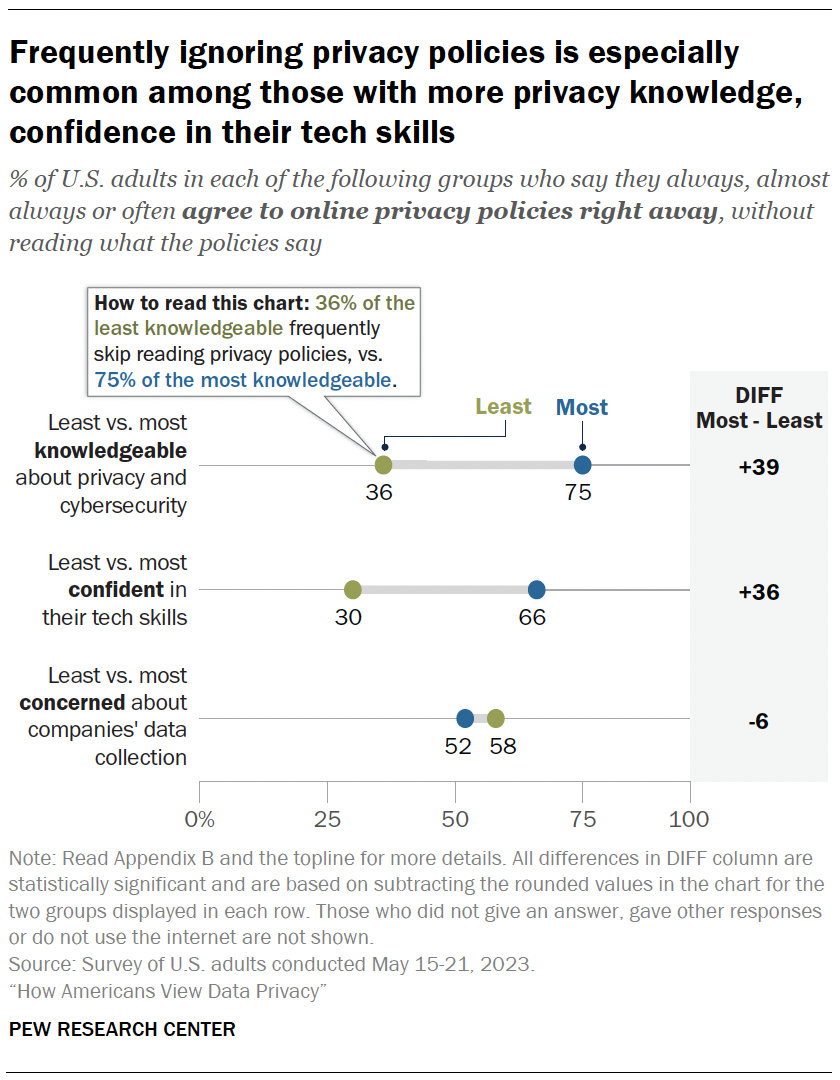

Ignoring privacy policies is especially common among those who are most knowledgeable or confident.

For example, three-quarters of the most knowledgeable say they frequently click “agree” without reading privacy policies. Among the least knowledgeable, that share drops to 36%.

This mirrors patterns by age and education discussed in Chapter 2. Younger adults and those with higher levels of formal education are especially likely to ignore online privacy policies. These groups also have more knowledge and confidence.

Age and knowledge

Within the most knowledgeable group, we still see that age matters:

- Some 84% of highly knowledgeable 18- to 29-year-olds frequently skip privacy policies.

- That share is 75% among those ages 30 to 49 and 70% of those 50 to 64.

- And it drops further to 59% among those 65 and older.