The Japanese economy has been anemic for years, with a 1.7% annual real growth rate in 2017 and 1.1% projected real gross domestic product growth in 2018, according to the International Monetary Fund. And less than half the public is pleased with the direction of the country and the economy.

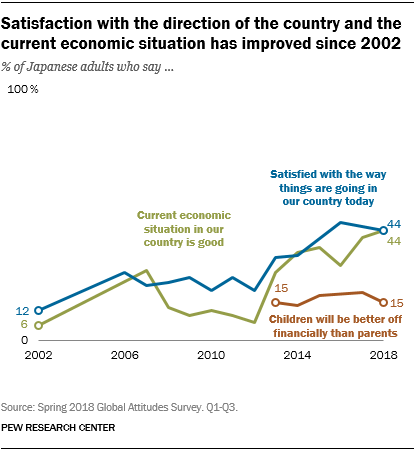

Nonetheless, Japanese are more satisfied with the way things are going in their country today (44%) and they feel better about the nation’s current economic situation (44%) than in 2002, when just 6% thought the economy was doing well and only 12% were content with the direction of the country.

However, this uptick in public satisfaction masks some nostalgia for the past and does not translate into hope for the future. About a quarter (26%) of Japanese believe that the financial situation of average people is better today than it was two decades ago. And only 15% of the public thinks today’s children will be better off financially than their parents, a pessimism that has not changed significantly in the last five years, despite improvement in the public mood about the economy.

There is disagreement between men and women on conditions in Japan today. Roughly half of Japanese men (49%) are satisfied with the direction of the nation, while 40% of Japanese women agree. More than half of men (52%) say the economy is good, but just 35% of women concur. While 30% of Japanese men assert that the financial situation of average people is better today than it was 20 years ago, only 22% of women agree. Notably, both men and women overwhelmingly believe that children today will be worse off financially than their parents.

Views of the economy are also divided along party lines. Among those with a favorable view of Prime Minister Abe’s party, LDP, 62% voice a positive view of the economy. By comparison, just 34% of backers of the opposition CDP say the economy is doing well.

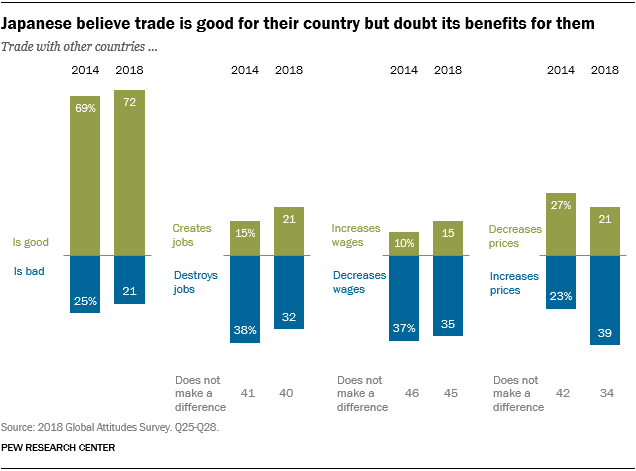

Japan is the fourth largest trading nation in the world, measured by imports and exports of merchandise. It runs a 4% trade surplus (as a percent of gross domestic product). And trade accounts for 17.1% of the country’s GDP, according to the World Trade Organization. The Japanese public seems to recognize the importance of the global market to their economy: 72% believe that growing trade and business ties with other nations are good for Japan. But Japanese are not so sure average people are benefiting directly from international commerce. Only about one-in-five (21%) believe that trade creates jobs or lowers prices, and roughly one-in-seven (15%) say trade leads to higher wages.

Men are more likely than women to hold the view that trade is good for the country (78% vs. 66%, respectively). People ages 18 to 29 are nearly twice as likely as those 50 and older to believe trade lowers prices. And Japanese with a higher level of education 1 or who have an income higher than the median are more likely than less educated people or those with lower incomes to think that trade creates jobs.

Japan is not only a leader in world trade. It is also among the leaders in automation. Japan has 303 installed industrial robots per 10,000 workers in the manufacturing industry, making it the fourth largest user of such robots in the world, according to a 2018 report by the International Federation of Robotics. And more automation may be coming: The average hourly cost of a manufacturing worker in Japan is about seven times the hourly cost of a robot, according to a study by Bain & Company.

The Japanese public is quite aware of these technological developments in the workplace and is generally wary of them.

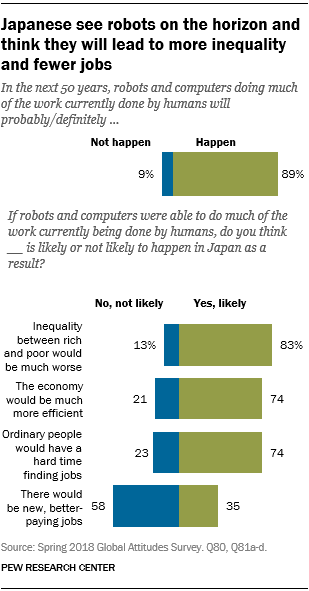

Nine-in-ten Japanese adults (89%) think that in the next half-century robots and computers will be doing much of the work currently done by humans. Japanese are much more likely to believe this about the future work world than Americans (65%). And 74% say the Japanese economy will be more efficient as a result, the largest share of the public to hold such views in a 2018 nine-country Pew Research Center survey on the topic.

For the most part, Japanese see more problems than benefits created by automation. More than eight-in-ten (83%) say inequality will get worse as robots do more human work. Roughly three-quarters of the public (74%) believe ordinary people will have trouble finding jobs in this new economy. And a majority (58%) do not believe automation will generate new, better-paying employment.

Young Japanese ages 18 to 29 are about three times as likely as those 50 and older to believe that in a half-century robots and computers will definitely do much of the work currently done by humans (52% vs. 17%, respectively). Younger adults are also significantly more likely than older adults to hold the view that automation will lead to new, higher-paying employment (52% vs. 31%, respectively).

Whatever their education level, more than half of Japanese do not think it is likely that automation will lead to more job opportunities. But those with a secondary education or less are particularly skeptical (61%).

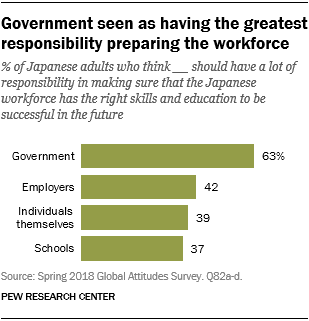

When asked who should be responsible for making sure that the Japanese workforce has the right skills and education to be successful in the future, a large majority of Japanese (63%) believe the government has a lot of that responsibility. Roughly four-in-ten (42%) say employers should bear much of the responsibility, 39% believe it should be individuals themselves and 37% say it should be schools.

Notably, those with a postsecondary education or higher are more likely than those with only a secondary education or less (45% vs. 35%, respectively) to voice the view that individuals bear a lot of responsibility in preparing themselves for employment in the new world of work.