Japanese feel better about their economy than at any time in nearly two decades. But the overall mood in Japan remains wary, if not pessimistic. The prevailing view is that average people are worse off than before the Great Recession, while few think the next generation will fare any better. Automation is one reason the future may not be so bright for ordinary people: Majorities of Japanese say growing reliance on robots and computers will lead to joblessness and income inequality. And less than half the public is satisfied with the way democracy is working in Japan, while more than half hold the view that politicians do not care about ordinary people, that they are corrupt and that elections ultimately do not change much.

These are among the key findings from a Pew Research Center survey conducted May 24 to June 19, 2018, among 1,016 respondents in Japan.

Mixed economic sentiment

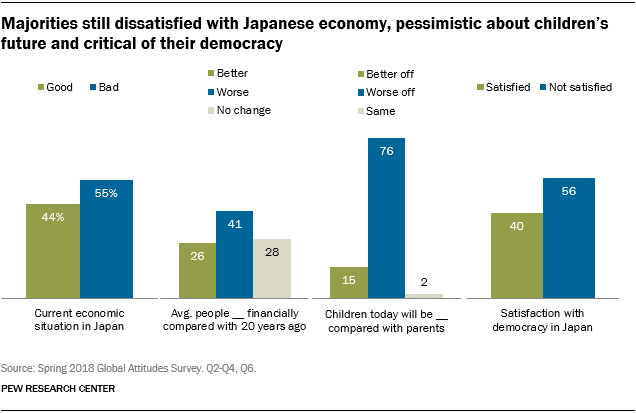

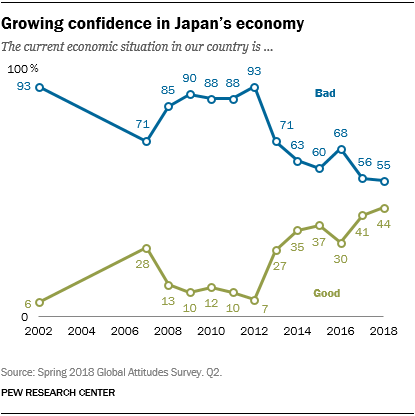

Positive views of the economy are up 34 percentage points since the early days of the global financial crisis in 2009. Nonetheless, in 2018 just 44% say the current economic situation in Japan is good, while 55% believe conditions are bad.

Four-in-ten Japanese (41%) think average people today are worse off financially than they were 20 years ago. Just 26% say they are better off. At the same time, only 15% of the public believes that children today in Japan will grow up to be better off financially than their parents, while 76% expect they will be worse off. That is among the lowest level of optimism about the next generation’s prospects among the 27 nations Pew Research Center surveyed in 2018.

Pessimism about the future may be tied in part to worries about automation. Nearly nine-in-ten members of the public (89%) believe that in the next half-century robots and computers will do much of the work currently done by humans.

And Japanese do not foresee that work environment as necessarily positive. More than eight-in-ten (83%) fear that such automation will lead to a worsening of inequality between the rich and poor, and more than seven-in-ten (74%) think ordinary people will have a hard time finding jobs.

But the fact is that without significant immigration there may be a deficit of people to employ. The nation’s population is aging and shrinking, the birth rate is projected to continue falling, and while immigration is on the rise, so is emigration. Japan’s population of 127 million is expected to shrink to 88 million by 2065.

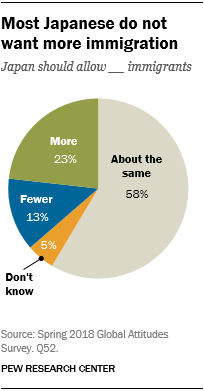

Many Japanese would appear unsettled by the perceived balance between emigration and immigration. Roughly six-in-ten Japanese (58%) say that people leaving their country for jobs in other nations is a problem. At the same time, an identical share believes that the government should keep immigration at its current level. Only 23% think Japan should allow in more immigrants; 13% want fewer entrants from other nations.

Reluctance to increase immigration does not appear to reflect public animus toward immigrants. Japanese believe that immigrants want to adopt Japanese customs and way of life (75%). They think immigrants make the country stronger because of their work and talents (59%). And they do not fear that immigrants are responsible for an increased risk of terrorism (60%) or more crime (52%).

Views of Prime Minister Abe and Japanese democracy

Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has now been in power since 2012 and is the third-longest-serving head of government in post-World War II Japanese history. He also served as prime minister for one year from 2006 to 2007, when he was the youngest prime minister to take office after WWII and the first to be born after it. He won re-election as head of the ruling, center-right Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in September 2018.

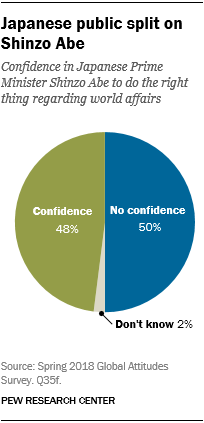

The Japanese public is divided in their view of the prime minister: 48% have confidence in him to do the right thing in world affairs, 50% lack such confidence. His support has fallen from a peak of 62% in 2015 and is now at its lowest since the Center first asked the question about Abe in 2007.

Not surprisingly, Abe’s strongest support (79%) comes from those who hold a favorable view of his party, the LDP. He also enjoys strong backing (69%) from followers of Komeito, a party with origins in a Buddhist sect and which is part of the current ruling coalition government. Abe’s weakest support (32%) comes from adherents of the center-left Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP). Men (54%) also favor Abe more than women (43%). And Japanese with more than a high school education (54%) are stronger backers of the prime minister than are those with a secondary education or less (45%).

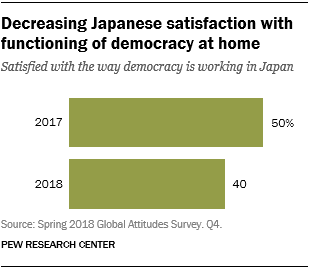

The decline in Prime Minister Abe’s support comes at a time of public dissatisfaction with the state of Japanese democracy. Just four-in-ten of those surveyed (40%) are satisfied with the way their democracy is working today. Such positive sentiment is down from 50% in 2017. At the same time, a majority of Japanese (56%) are dissatisfied with their democracy, up 9 percentage points from 2017.

The public is particularly cynical about some aspects of their democracy. They believe that elections don’t change things (62%), that elected officials don’t care what ordinary people think (62%) and that most politicians are corrupt (53%).

Yet they praise their democracy for its protection of freedom of speech (62%) and the fairness of the courts (54%).

Views of the U.S. and China

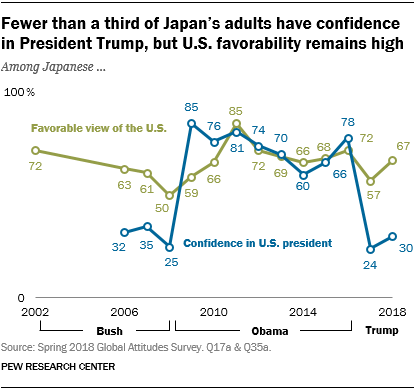

Japanese views of the United States took a tumble in 2017 and their opinion of the American president fell precipitously. Both viewpoints recovered somewhat in 2017.

Two-thirds (67%) of the Japanese public holds a positive opinion about America, up 10 percentage points from 2017. This assessment of their longtime ally is roughly comparable to the median Japanese public opinion of the U.S. during the Obama administration.

But only three-in-ten Japanese express confidence in U.S. President Donald Trump’s handling of world affairs. This judgment is up 6 percentage points from that in 2017. But it is 45 points below the median level of Japanese confidence in his predecessor, Barack Obama, over his two terms in office.

Japanese also express a growing belief that the U.S. acts unilaterally (71%) when conducting American foreign policy, not taking into consideration Japan’s concerns. And 43% say America is doing less than it did a few years ago to address global problems.

Nevertheless, 64% believe that relations between Japan and the U.S. have stayed about the same over the past year. And, when asked whether they would prefer the U.S. or China to be the world’s leading power, eight-in-ten Japanese (81%) choose America. The Japanese public’s preference for U.S. leadership is stronger than it was in any of the other 25 nations surveyed by Pew Research Center in 2018.

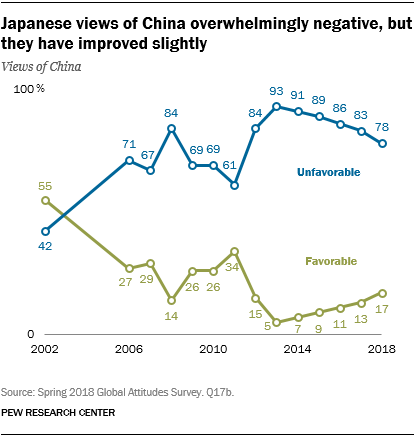

Japanese views of their neighbor China have also improved somewhat over time, but from a very low base. Just 17% of the public holds a favorable impression of China, up 12 points from a low of 5% in 2013. Unfavorable opinion of Beijing has fallen 15 points since then, to 78%.

Such public animosity toward China is also seen in the finding that about three-quarters of Japanese (76%) lack confidence in China’s President Xi Jinping. And according to a 2017 Pew Research Center report, roughly two-thirds (64%) believed China’s power and influence was a major threat to Japan.