Overview

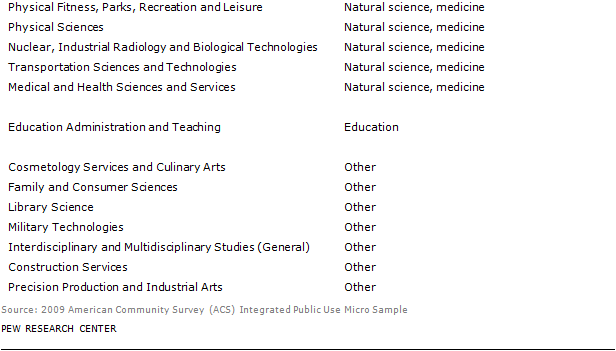

The typical college graduate earns an estimated $650,000 more than the typical high school graduate over the course of a 40-year work life, according to a new analysis of census and college cost data by the Pew Research Center.

Of course, this difference doesn’t apply in all cases; some high school graduates are high earners, and some college graduates are low earners. Also, the monetary return to college is influenced by a variety of factors, including type of college attended and major field of study.

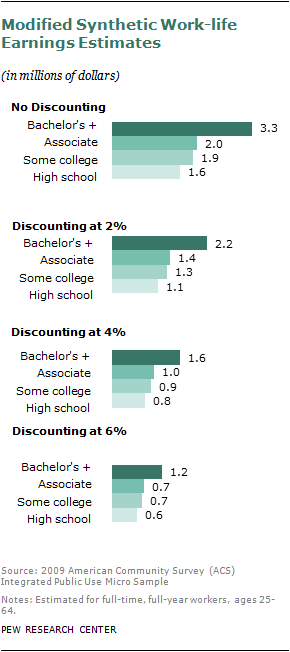

But on average—and after taking into account the fact that a dollar earned at the start of someone’s working life is more valuable than a dollar earned toward the end of that person’s working life18—the analysis finds that the typical or average high school graduate with no further education earns about $770,000 over a 40-year work life. The typical worker with a (two-year) associate degree earns about $1.0 million, and the typical worker with a bachelor’s degree and no advanced degree earns about $1.4 million.

Balanced against these work-life earnings differences are the upfront costs of time and money associated with getting a college degree. Today’s typical high school graduate ages 18 to 24 with no further education is paid about $23,000 working full time, full year. Thus, foregone earnings approach $50,000 for someone with an associate degree and approach $100,000 for someone with a bachelor’s degree, assuming that the undergraduate completes an associate degree in two years and a bachelor’s degree in four years.

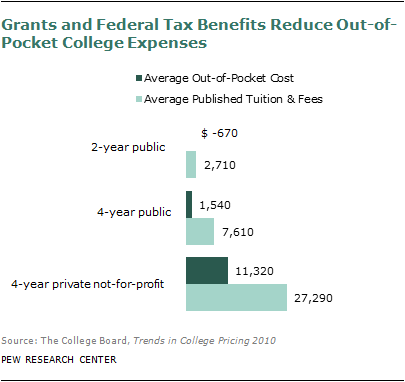

The out-of-pocket expenses for tuition and fees vary significantly, depending on where the student attends college. The College Board estimates that, after student aid and federal income tax benefits are accounted for, the average tuition and fees paid is close to zero for students attending community colleges.19 For undergraduates attending in-state, public four-year colleges and universities, the College Board estimates that the average price after aid is about $1,500 per year. The typical student at a private, nonprofit four-year institution pays about $11,300 in tuition and fees per year after aid and tax benefits are considered.

When these costs of attending college and the foregone earnings are subtracted from the income benefits over the course of a lifetime, the net “payoff” from getting a college degree is still quite substantial. For a typical student who graduated from an in-state, four-year public university, this net gain is about $550,000, the analysis finds.

However, this average figure masks wide variations in the financial returns to a college education. On the benefit side of the equation, work-life earnings tend to be much higher for undergraduate majors requiring numerical competencies (computers and engineering) than other fields of study (education and liberal arts). In regard to costs, some colleges and universities have much higher tuition and fees than the typical in-state public institution. In addition, some undergraduates do not receive aid and may pay the full tuition and fees listed. About two of three undergraduates receive some form of grant aid, and the amount of grant aid tends to decline as the student’s family income increases.

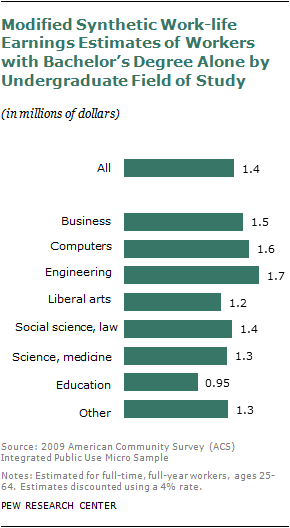

Based on average earnings and cost data, some college degrees may not have generous payoffs. For example, the estimated total work-life earnings of a typical worker with a bachelor’s degree in education and no advanced degree are about $950,000. This exceeds the work-life earnings of the typical high school graduate by only $180,000. Foregone earnings alone would tally about $100,000. Four years of tuition and fees at some college and universities could exceed the remaining $80,000 benefit, particularly if the education major is from an affluent family and does not receive any grant aid or federal tax benefits.

The Pew Research estimates for work-life earnings are based on the current patterns of earnings differences by education in the most recent census data. However, returns to education in the labor market have changed over time. Extensive research on this subject shows that the payoff for a college education increased substantially during the 1980s, then, depending on the details of measurement, either increased slightly since the early 1990s or plateaued.20 Whether the returns to education will decline in the future is not known. Many economists would surmise that the future course of the financial returns to schooling in part depends on how many young people pursue and complete college. If college-educated workers become relatively less scarce, the financial returns to college might decline.

Terminology for Chapter 5

“Full-time, full-year worker” refers to persons who worked at least 48 weeks in the prior year and reported usually working at least 36 hours per week.

“High school graduate” refers to a person who completed high school but did not obtain any college education. The person may have completed high school by obtaining a regular high school diploma or the equivalent (e.g., GED).

The educational attainment level “some college” refers to the completion of some college credits (regardless of the number of years) but not a higher education degree. Persons who reported that their highest education was completion of an associate degree are not included in the “some college” category.

“Professional degree” refers to a degree beyond the bachelor’s degree that fulfills the academic requirements for beginning practice in a profession. The U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey gives the following examples of a professional degree on the questionnaire: M.D. (medicine), D.D.S. (dentistry), D.V.M. (veterinary medicine), LL.B. or J.D. (law). The survey instructions inform respondents to “NOT include post-bachelor’s certificates that are related to occupational training in such fields as teaching, accounting, or engineering.” Though not given as examples on the questionnaire, individuals who have completed the degree required for optometry (O.D.), pharmacy (D.Phar.), chiropractry (D.C. or D.C.M.), and theological professions (e.g., M.Div.) presumably would self-report as possessing a professional degree.

“Advanced degree” holders are individuals whose highest educational attainment is a master’s degree, professional degree or doctorate.

The Big Payoff

Each year millions of college students devote significant time and expenditures to obtain a college education. Many of them enroll with the expectation of a “payoff” from their educational endeavors—that is, the monetary gains from the pursuit of higher education will outweigh the monetary costs. A prominent 2002 Census Bureau study, “The Big Payoff,” examined the accumulated earnings gains over an adult’s work life from additional education and suggested that the payoffs may be quite large. The typical worker with a bachelor’s degree was estimated to make nearly $1 million more over that worker’s work life than a high school graduate. This chapter revisits the analysis of the original Census Bureau study using more recent earnings data, revised methodology and more detail on the higher education degree. It also assesses the typical monetary costs of higher education and provides some estimates of the life-time payoffs to higher education by balancing the estimated work-life earnings gains with the upfront costs of higher education.

Work-life Earnings

The likelihood that a person lands a job and the number of hours the person works depend on the level of education. In this analysis, we ignore differences in the amount of hours that people work and concentrate on what employers are willing to pay employees who work the same amount of hours. That is, the earnings data and calculations are for “full-time, full-year” workers.

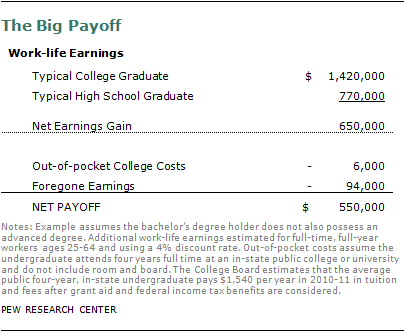

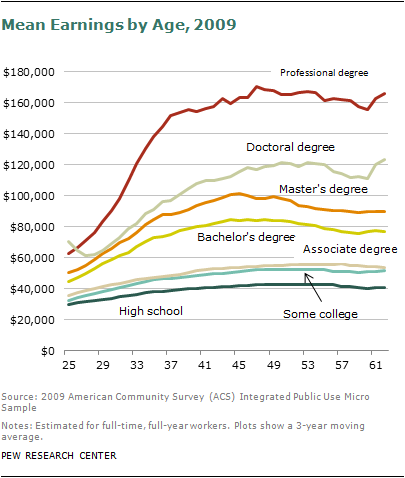

The typical young worker with a bachelor’s degree earns significantly more than the typical worker who did not pursue any further formal education beyond high school. In 2009, the average 25- to 29-year-old worker with at least a bachelor’s degree earned almost $50,000 per year. The 25- to 29-year-old who finished a high school education typically earned about $31,000. The average young worker with an associate degree earned about $37,500.

The earnings differences by education measured early in the work life do not take account of the different earnings trajectories or earnings paths of workers. The earnings of workers with lesser amounts of education tend to not grow as much as the earnings of more educated workers as their careers unfold. As a result, the difference in average earnings across education groups gets larger as workers age.

It is impossible to know how much young workers today will earn over the remainder of their work life. “Synthetic” estimates of work-life earnings calculate how much workers will earn over their work lives if their earnings path were to mirror the age profile of the most recent data snapshot. In other words, today’s young workers are assumed to eventually earn what today’s older workers earn.

Length of work life might vary by education, but typically a 40-year work life is assumed, and estimates of work-life earnings are based on full-time, full-year earnings from ages 25 to 64 (Census Bureau, 2002; Baum, Ma and Payea, 2010). Assuming that work life commences by age 25 seems reasonable for most workers. Most people with at least a bachelor’s degree obtain the degree before age 25, and the modal age is 22 or younger (National Center for Education Statistics, 2003). Assuming completion of a bachelor’s degree at age 22, many workers with advanced degrees could commence their careers by age 25. From initial enrollment in graduate school, it typically takes a student three years to complete a master’s degree and four years to complete a professional degree (National Center for Education Statistics, 2007). For workers who have a doctorate, starting work at 25 might be a bit more problematic. It typically takes graduate students six years to complete a doctorate. But anecdotal evidence suggests that many workers with doctorates can work long beyond 64 years of age. Tenured college and university professors are no longer mandated to retire at age 70, and some work beyond 70. The estimates of work-life earnings presented here are based on the standard work span of 25 to 64 years of age.

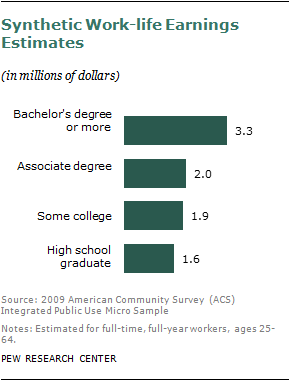

As the figure on page 88 suggests, differences in earnings by education add up over a work life. The typical high school graduate would be expected to earn about $1.6 million over 40 years. Workers whose highest education is an associate degree earn $2.0 million, and the synthetic work-life estimate for workers with at least a bachelor’s degree is $3.3 million.

The accompanying figure updates the 2002 Census Bureau estimates, but these estimates are problematic because they assume that $1 in future earnings has the same value as $1 earned today, i.e., the future earnings were not discounted. Over a 40-year horizon, discounting makes a significant difference; the figure on the next page shows the extent to which work-life earnings estimates diminish if discounting is applied. For example, discounting future earnings at a 4% rate, the present value of what the typical worker who has completed high school but no further formal education would be expected to earn over a 40-year work life is $0.8 million. A worker with an associate degree would earn $1.0 million over 40 years, and a worker with at least a bachelor’s degree would earn about $1.6 million after discounting is applied to future earnings.

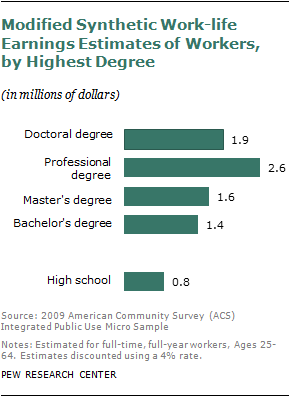

By Degree. Some of the workers who have a bachelor’s degree have also attained advanced degrees. On average, those with advanced degrees earn more than workers who have no more than a bachelor’s degree, and they have higher estimated synthetic work-life earnings. Assuming a 4% discount rate, workers whose highest degree is a bachelor’s degree earn about $1.4 million from 25 to 64 years of age. A high school graduate earns about $0.8 million over a 40-year work life, so the attainment of a bachelor’s degree typically adds about $0.6 million in earnings. Workers with a master’s degree typically earn $1.6 million from age 25 to 64, only $0.2 million more than workers who completed their education at a bachelor’s degree. A much larger addition to work-life earnings tends to be obtained by workers with a professional degree. Those with professional degrees average $2.6 million in work-life earnings, $1.2 million more than a worker with a bachelor’s degree alone and six times the gain to work-life earnings from obtaining a master’s degree.

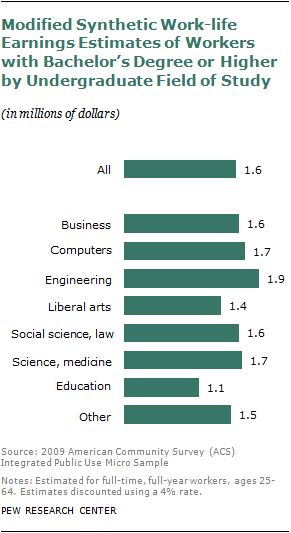

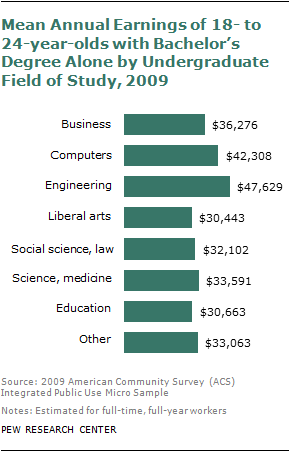

By Undergraduate Field of Study. The monetary rewards of a college education tend to vary by undergraduate field of study as well as by the degree earned. The American Community Survey (ACS) collects data on undergraduate field of study for all persons with at least a bachelor’s degree. By broad field of undergraduate major, workers with at least a bachelor’s degree who majored in engineering earn about $1.9 million over a work life. Their counterparts with a major in education would earn on average about $1.1 million.

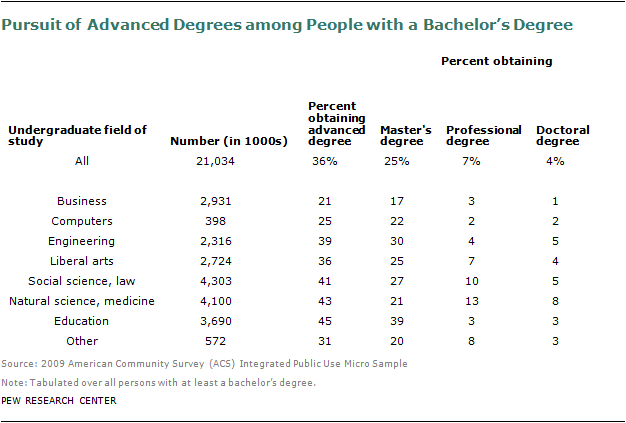

These work-life earnings returns by undergraduate field of study partly reflect the differing propensities of people with bachelor’s degrees to obtain advanced degrees. In 2009, about 59 million people had at least attained a bachelor’s degree. Of these, about 21 million (36%) had attained an advanced degree. The likelihood of having an advanced degree varies by undergraduate field of study. Undergraduate majors in education are the most likely to have an advanced degree (45%). People with a bachelor’s degree in the broad field of study “business” were the least likely to have an advanced degree (21%).

Among workers with a bachelor’s degree but not an advanced degree, the estimated 40-year work-life earnings range from $0.9 million for workers with an education degree to $1.7 million for workers with an engineering degree. Workers with undergraduate majors that require mathematics competencies tend to earn the most over their work lives.

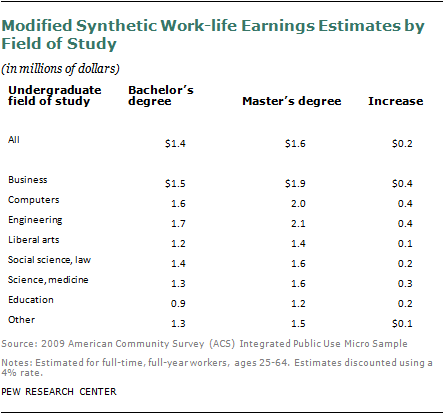

The Earnings Gain from a Master’s Degree. The most prevalent advanced degree is a master’s degree, and typical workers who have one earn an estimated $1.6 million over their work life in comparison to $1.4 million for workers with a bachelor’s degree alone. The increment to work-life earnings varies by undergraduate field of study. Undergraduate majors in the liberal arts field of study who then get a master’s degree tend to earn $0.1 million more in work-life earnings than workers with only a liberal arts bachelor’s degree. Workers with bachelor’s degrees in business, computers and engineering tend to obtain the greatest boost to work-life earnings from completing a master’s degree ($0.4 million).

The reader should bear in mind that in the ACS we don’t know the field of study of the master’s degree. The ACS reveals only the major field of study of the respondent’s bachelor’s degree. It is not possible using the ACS to investigate the earnings of workers with master’s degrees by the field of the master’s.

Limitations of the Analysis of Work-life Earnings

The above estimates of work-life earnings reflect the current patterns of educational returns in the U.S. labor market. Currently, on average, employers are willing to pay workers with associate degrees and bachelor’s degrees more than workers who did not pursue any formal education beyond high school. It is not known if these educational premiums will persist in the future. Over the past 20 years, the returns to education seem to be quite stable.

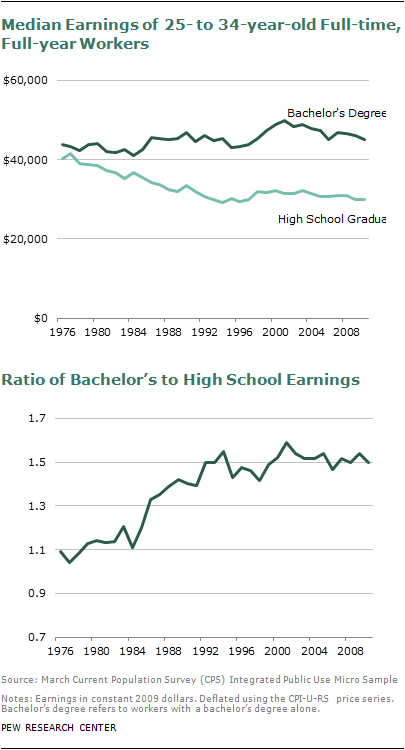

It is typically surmised that new developments in the wage structure will be observed first among young, less-experienced workers. These workers are relatively new entrants to the labor market. The charts on the following page plot the change over the past 35 years in median earnings of 25- to 34-year-old full-time, full-year workers (all dollar amounts adjusted for inflation). The median earnings of 25- to 34-year-old workers with a bachelor’s degree have remained stable around $46,000 per year since 1976. Earnings of high school graduates with no further education fell during the 1980s and have stabilized at around $30,000 since the early 1990s. As a result, the college to high school earnings premium increased from 1.1 in 1976 to 1.5 by 1992. In March 2010, the ratio was 1.5. The earnings premium for college-educated workers has been stable over the past 20 years in spite of the fact that there has been growth in the supply of college-educated labor. In 1990, 23% of 25- to 29-year-olds had at least a bachelor’s degree. In 2010, 31% of 25- to 29-year-olds had at least a bachelor’s degree.

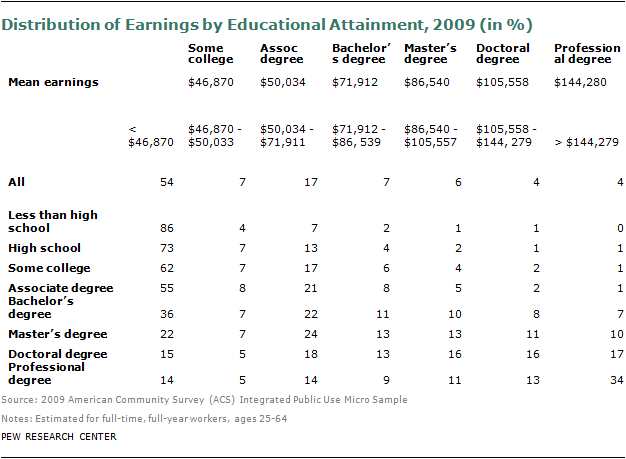

Work-life earnings estimates utilize the averages (or means) of what workers earn. Means are measures of central tendencies, and while it is true that most workers with less education earn less than workers with college degrees, a few less-educated workers are relatively very highly paid. The first row of the Table below reports the mean earnings of workers by education. The following rows report the earnings distribution for each group of workers by education, where the intervals correspond to the means above. So, for example, 73% of workers with a high school education but no college earn less than what the average worker with some college earns ($46,870). Only 8% earn at least what the typical worker with a bachelor’s degree alone earns ($71,912). As the table shows, the reverse is also true. Not all highly educated workers are relatively highly paid. For example, 36% of workers with a bachelor’s degree alone are paid less than the typical worker with some college ($46,870).

The Big Payoff: More than Just Earnings

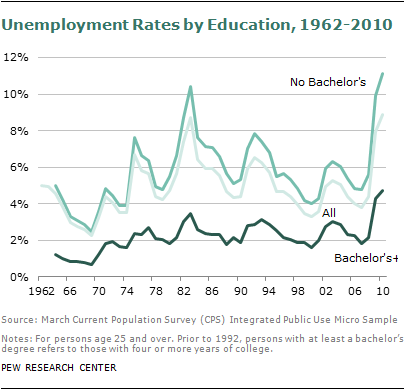

In addition to earning more, on average, than other workers, persons with more education generally have more stable employment patterns. They are more likely than those with less education to be employed, to work full-year and to work greater amounts of hours if they so choose. For example, in March 2010 the unemployment rate of persons without a bachelor’s degree was 11%. The comparable unemployment rate for persons with at least a bachelor’s degree was 5%.

This gap has persisted for many decades, and through multiple ups and downs of the economy.

As noted earlier, the “big payoff” analysis presented in this chapter captures only the direct earnings gains associated with higher education. If one were to factor in the greater likelihood of being employed among those with higher levels of educational attainment, those money benefits would grow larger. In addition, increased education appears to have substantial benefits for individuals beyond the labor market (Wolfe and Haveman, 2002). Greater education is associated with improvements in one’s health (in fact, some of the earnings differences across education groups may be occurring as a result of health improvements). A vast literature shows that parental education has large impacts on children’s health and subsequent success in life. Education is increasingly associated with the likelihood that a person gets married and affects the stability of marital unions (Lefgren and McIntyre, 2006). The benefits of additional schooling beyond the labor market may be sizable. As one reviewer recently observed: “Large amounts of money appear to be lying on the sidewalk. Of course, money isn’t everything. In the case of the returns from schooling, it seems to be just the beginning” (Oreopoulos and Salvanes, 2011).

Out-of-Pocket Costs of Higher Education

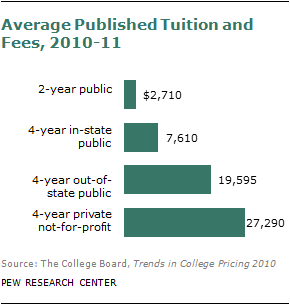

Undergraduate Education. The cost of acquiring a college education partly depends on which college or university the student attends. On the basis of an annual survey of the nation’s colleges and universities, the College Board compiled the average tuition and fees charged full-time undergraduates for the 2010-11 academic year. The “sticker price,” or the published tuition and fees, ranged from an average of $2,700 per year at public two-year colleges to an average of over $27,000 at private not-for-profit four-year colleges and universities.

Most undergraduates do not actually pay the sticker price because more than six-in-ten full-time, full-year undergraduates receive some grant aid that reduces the out-of-pocket annual expenses for college. In addition, some students and their families obtain federal income tax credits or deductions for higher education expenses that effectively reduce college expenses. After accounting for the estimated average grant aid and federal tax credits, the College Board estimates that the average net price of attending a public two-year college is less than zero. The average annual out-of-pocket expenses at public four-year college and universities for in-state students is $1,540 per year; at private, not-for-profit, four-year colleges and universities, it is slightly more than $11,000 per year.

These figures underestimate out-of-pocket college expenses because they do not include expenses for books and supplies and for transportation costs. Based on institutional budgets for students as reported by college and universities in the annual survey, the College Board estimates that books and transportation typically cost the undergraduate an additional $2,000 per year (College Board, 2010).

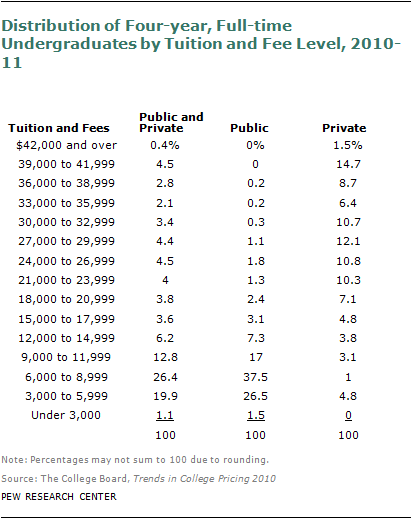

The published tuition and fees reported in the figure on page 100 are enrollment-weighted averages and they may not seem consistent with news accounts of private not-for-profit tuition and fees eclipsing the $50,000 mark. First, most full-time undergraduates do not attend private colleges and universities. Nearly two-thirds of the nation’s full-time undergraduates at four-year colleges and universities are at public institutions. Second, even in the private sphere, there is a distribution of students across a range of colleges that vary in their published price. According to the College Board, about a quarter of private full-time undergraduates are at colleges and universities with announced tuition and fees at or above $36,000 per year. These students represent less than 10% of the nation’s full-time, four-year undergraduates. Perhaps not surprisingly, most students do not attend the nation’s most expensive colleges and universities.

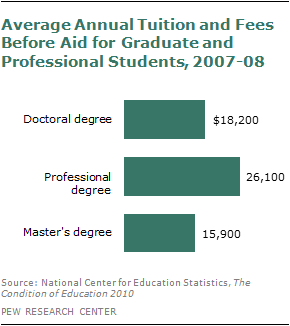

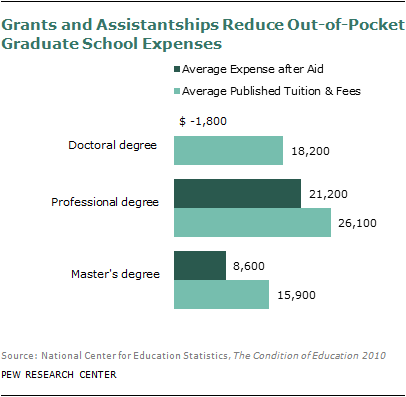

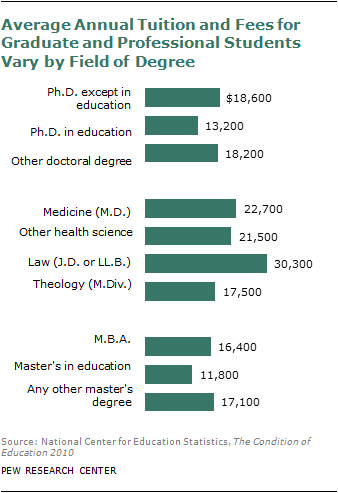

Graduate and Professional Education. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) provides similar estimates of the cost of pursuing advanced degrees. For the 2007-08 academic year, the average full-time student paid about $16,000 in tuition and fees to pursue a master’s degree and around $18,000 for a doctoral degree. Students pursuing professional degrees typically paid about $26,000. Again, these figures slightly underestimate expenses because they do not include expenses for books and supplies and for transportation. Although grant aid is not as pervasive for students pursuing advanced degrees as for undergraduates, grant aid does reduce out-of-pocket expenses for some graduate and professional students. According to NCES, more than 40% of full-time graduate and professional students received some grant aid, and a majority of those students pursuing a doctoral degree receive an assistantship.

After aid, the typical full-time student pursuing a master’s paid around $9,000 per year in 2007-08. The average student seeking a professional degree paid about $21,000 after aid. Accounting for aid and assistantships, the average full-time student pursuing doctoral degrees paid net tuition and fees of less than zero in 2007-08.

The NCES figures are averages, and some full-time graduate and professional students will pay out-of-pocket expenses for their advanced degrees in excess of these figures. For example, while the average student pursuing a professional degree paid $26,000 in tuition before any aid, students at law school pursuing a J.D. or LL.B. degree typically paid about $30,000 per year (before aid) in 2007-08.

Foregone Earnings: Typically the Biggest Expense

For many students, the value of their time and effort devoted to academic studies is a larger cost than the out-of-pocket expenses for tuition and fees. Rather than being in school, the student could be employed. The average high school graduate ages 18 to 24 and working full time, full year earned $23,400 in 2009. These foregone earnings trump the out-of-pocket expenses of the average undergraduate at an in-state public institution as well as those of many students at private colleges and universities.21

Foregone earnings are also probably a more sizable cost for students pursuing advanced degrees. These students already have at least a bachelor’s degree and, on average, what they could earn in the labor market is greater than the typical undergraduate. Foregone earnings for students pursuing advanced degrees probably depend on their undergraduate major field of study. Typical annual earnings for 18- to 24-year-olds with a bachelor’s degree range from $30,000 for liberal arts majors to nearly $48,000 for engineering majors.

The Big Payoff?

Based on average earnings and costs, and assuming a 4% discount rate, the completion of many higher education degrees might be expected to pay off in that the additional gains in estimated work-life earnings exceed the out-of-pocket college expenses and foregone earnings. The net payoffs typically are in the six-digit range rather than the seven digit range, and for some fields of study may be negligible. The section that follows looks at some examples.

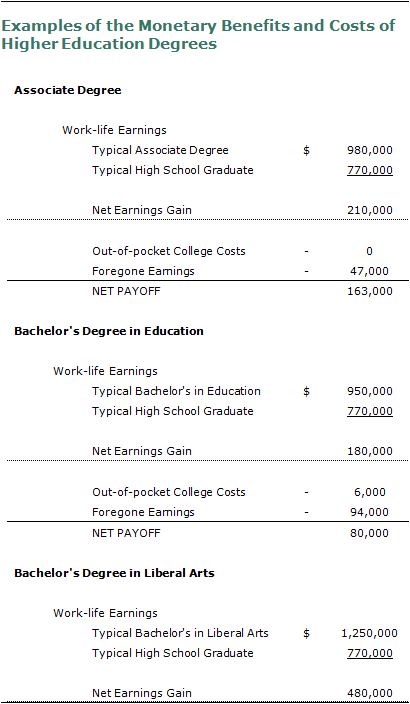

Associate Degree. Over a 40-year work life, a worker with an associate degree earns an estimated $0.21 million more over a worker with no schooling beyond high school. After aid and federal tax benefits, the out-of-pocket cost of acquiring an associate degree is minimal. However, a youth would forego two years of earnings (around $50,000) to obtain the associate degree. The estimated work-life earnings gains seem to exceed the present costs.

Bachelor’s Degree. The added earnings from most bachelor’s degrees seem to exceed the typical costs to acquire them, but bachelor’s degrees in some fields of study seem to be on the bubble. Consider a bachelor’s degree in education. The estimated work-life earnings gain of a worker with a bachelor’s degree in education and no advanced degree is less than $200,000. Assuming four years of undergraduate study are required to complete the bachelor’s degree, the undergraduate will forego about $94,000 in earnings. The out-of-pocket expenses to acquire the degree depend partly on which college or university the student attends. Supposing that the student attends in-state, full-time at a public four-year institution, then the out-of-pocket expenses, according to the College Board, average $1,540 per year, or about $6,000. In this example, the payoff is in the tens of thousands of dollars, and it is not clear that a bachelor’s degree in education automatically pays off over a work life. Education majors attending more expensive college and universities and lacking generous aid packages may not experience large net payoffs.

Work-life earnings estimates suggest bachelor’s degrees in other fields of study have higher payoffs. The typical worker with a bachelor’s degree in a liberal arts field and no advanced degree earns an additional $0.48 million over 40 years compared with a high school graduate who has no further formal education. Unless the degree is obtained at a very expensive college and university and no grant aid is received, it is highly likely that the added earnings will exceed the costs by a comfortable margin.

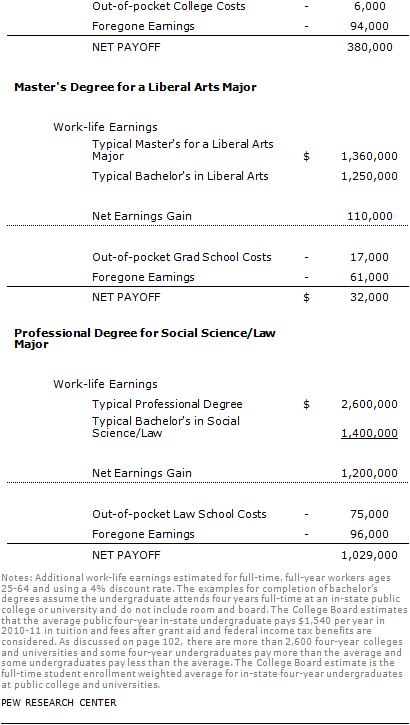

Master’s Degree. A typical master’s degree completed early in life likely pays off. Suppose that a master’s degree can be completed in two years of full-time graduate education beyond the bachelor’s degree. Using an instance where the earnings data suggest that the payoffs tend to be more modest, consider a youth with a bachelor’s degree in a liberal arts field. The additional work-life earnings from obtaining a master’s are $0.11 million above the earnings of a worker with a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts. In this instance, the payoff is not large. The out-of-pocket tuition fees average $17,200 and the foregone earnings might be around $61,000. The additional work-life earnings exceed the upfront costs, but again in tens of thousands of dollars, not hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Law Degrees. Law degrees (J.D. or LL.B.) are far and away the most popular professional degree conferred, and work-life earnings estimates suggest that they have a sizable earnings benefit relative to the costs of acquiring the law degree. Consider a young person with a bachelor’s degree with an undergraduate major field of study in social science/law. The NCES tuition figures indicate that the out-of-pocket cost of three years of law school after aid will average about $75,000. Again, foregone earnings trump this, as a worker with a bachelor’s degree in social science/law will forego about $32,000 per year (or a total of $96,000) to pursue law school. The added work-life earnings gains from having a law degree likely exceed the $170,000 costs by several-fold. The 2009 ACS does not allow us to estimate the work-life earnings of workers with a law degree. The work-life earnings of workers with professional degrees are $2.6 million, far in excess of the $1.4 million work-life earnings of a worker with a bachelor’s degree in social science/law. The $2.6 million figure of professional degree holders might overestimate what a worker with a law degree will make over a 40-year work life, because it includes the earnings of workers with medical degrees (at the same time, the $2.6 million figure also includes the earnings of religious workers with theology degrees). But a reasonable expectation is that the added increment to work-life earnings from having a law degree far exceeds the $170,000 cost of acquiring it.

Appendix I to Chapter 5: Methodology and Estimation Issues

Synthetic work-life earnings estimates assume that a worker’s earnings stream will mimic the most recent age-earnings profile. Following Census Bureau (2002), the synthetic work-life earnings estimates are calculated by:

Synthetic work-life earnings =

is average earnings and i refers to age. Although the underlying sample sizes are quite large in the American Community Survey (see below), providing estimates by educational attainment and field of study does make demands on the statistical reliability of the data. So, following Census Bureau (2002), average earnings were computed not for each age but rather for five-year age groups: ages 25-29, 30-34, …, 60-64. As mentioned in the text, synthetic work-life earnings do not discount earnings received later in the work life. The modified synthetic work-life earnings presented apply appropriate discounting:

Modified synthetic work-life earnings =

where r is the discount rate.

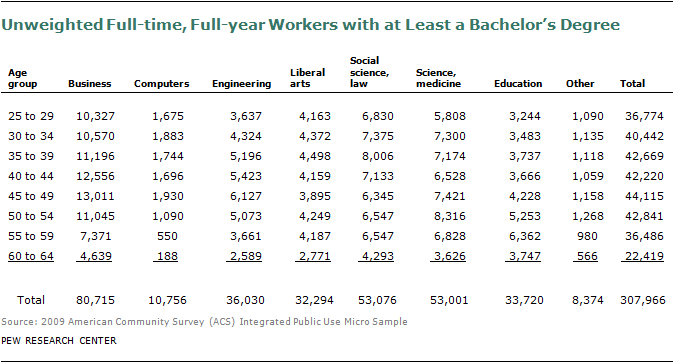

The 2009 American Community Survey Integrated Public Use Micro Sample (IPUMS) is about a 1% sample of the resident population and has records of 3,030,728 people. There are 865,000 full-time, full-year workers ages 25 to 64 in the 2009 ACS. Of these, 823,000 report having positive wage and salary income in the prior year. This is the underlying sample used for the analysis. By age group and undergraduate field of study, the following table reports the unweighted sample sizes for workers with at least a bachelor’s degree:

Wage and salary income is top-coded in the 2009 ACS. The top-code varies by state. Median earnings are unaffected by top-codes but mean earnings statistics are. The estimates reported are based on the wage and salary income in the data file. Top-coding likely affects the mean earnings of workers with professional degrees the most as they tend to be the highest earning workers.

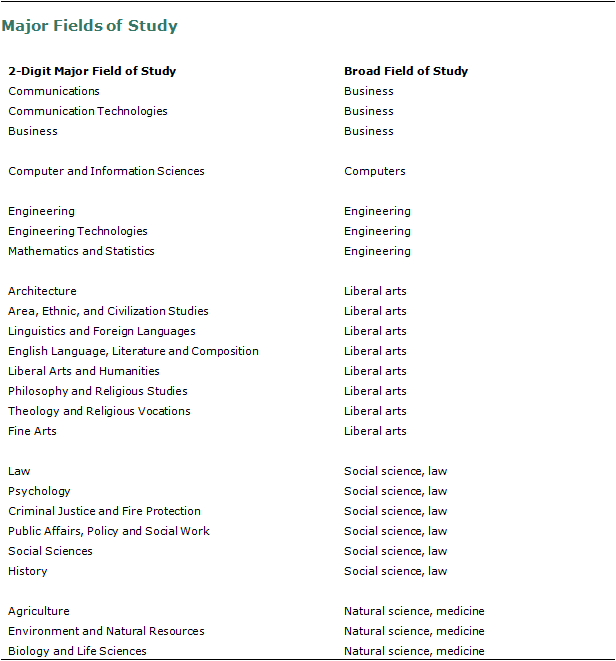

Appendix II to Chapter 5: Major Fields of Study

The 2009 American Community Survey identifies 37 undergraduate major fields of study. Following Census Bureau (2005), the individual majors were aggregated into eight broad fields of study: