Some respondents simply answer that they live outside the U.S.

One way to measure how many people taking a poll do not actually live in America is simply to ask. A question in the study did just that, asking respondents whether they currently live “outside the U.S.” or “inside the U.S.” While informative, such a measure has notable limitations. If a foreign respondent is aware that they do not belong in a U.S. survey, they are unlikely to answer truthfully. Several research teams have documented this scenario of foreign respondents taking steps to conceal themselves in U.S. research using an online crowdsourced platform.

Another possibility is that some people answering “outside the U.S.” are Americans temporarily living or traveling abroad. This situation is common, for example, with members of the U.S. military. Such people might vote in U.S. elections and in other respects still be part of “American public opinion.” Given that only a small fraction of Americans live abroad, however, we would expect the share accurately reporting living abroad in a secure, representative survey to be very low.

Finally, some answers to this question may reflect measurement error from respondents who are either trolling or answering haphazardly. This form of error stands to bias estimates up while foreign respondents lying about their location would bias estimates down.

While rare in all samples, the share of respondents self-reporting that they currently live outside the U.S. was higher for the opt-in samples than for the address-recruited samples. Among the opt-in sources, the incidence ranged from 1% (crowdsourced sample and opt-in panels 2 and 3) to 2% (opt-in panel 1). There were some respondents giving that answer in the address-recruited panel samples, but their incidence rounds to 0%.

One of the two ABS panels is Pew Research Center’s own American Trends Panel, allowing us to examine whether any of those panelists reporting that they live abroad actually do based on the mailing address that we have on file for them. This check showed that none of the panelists had a mailing address outside the U.S. This suggests that for the address-recruited panels the trace-level reports of living abroad probably reflect measurement error (e.g., from satisficing) or panelists who are traveling.

A self-report of living outside the country was strongly associated with other signs of bad response behavior. For example, giving multiple non sequitur open-ended answers was much more common among those saying they live outside the U.S. than inside the U.S. (42% versus 2%, respectively). Also, 12% of the respondents self-reporting that they live outside the U.S. completed the survey using a foreign IP address. By comparison, 1% of the respondents self-reporting that they live inside the U.S. completed the survey using a foreign IP address.

On a related note, some opt-in panel polls included a few respondents appearing to answer open-ended questions in a foreign language. The survey was administered in English and Spanish only. But when asked “How would you say you are feeling today?,” an opt-in panel 2 respondent answered in Pashto (“هحختهح نتهخ”), and an opt-in panel 3 respondent answered in Portuguese (“Sim e muito bom”). Both reported that they currently live outside the country. No foreign language (non-English and non-Spanish) responses were detected for the crowdsourced sample or either of the address-recruited panels, though there are many instances of low English proficiency in the crowdsourced sample. Use of these foreign languages is not in itself proof that the respondents do not belong in a U.S. opinion poll, but it is suspicious – particularly alongside a self-report of living outside the U.S.

About one-in-20 crowdsourced respondents have a foreign IP address

IP address is another useful, though imperfect, piece of information about where online poll respondents live. In general, the geolocation of an IP address is a useful indicator of an internet user’s approximate location. But differences between the user’s location and their IP address location can and do arise from several factors. Those include: where the owner of the IP has it registered, where the agency that controls the IP is located, and proxies. For example, it is common for users on the Verizon network who live in the northern U.S. to show a Canadian IP because that is where the controlling agency of the IP is located. Due to such discrepancies, the geolocation of an IP location alone cannot be considered conclusive evidence about where individuals live.

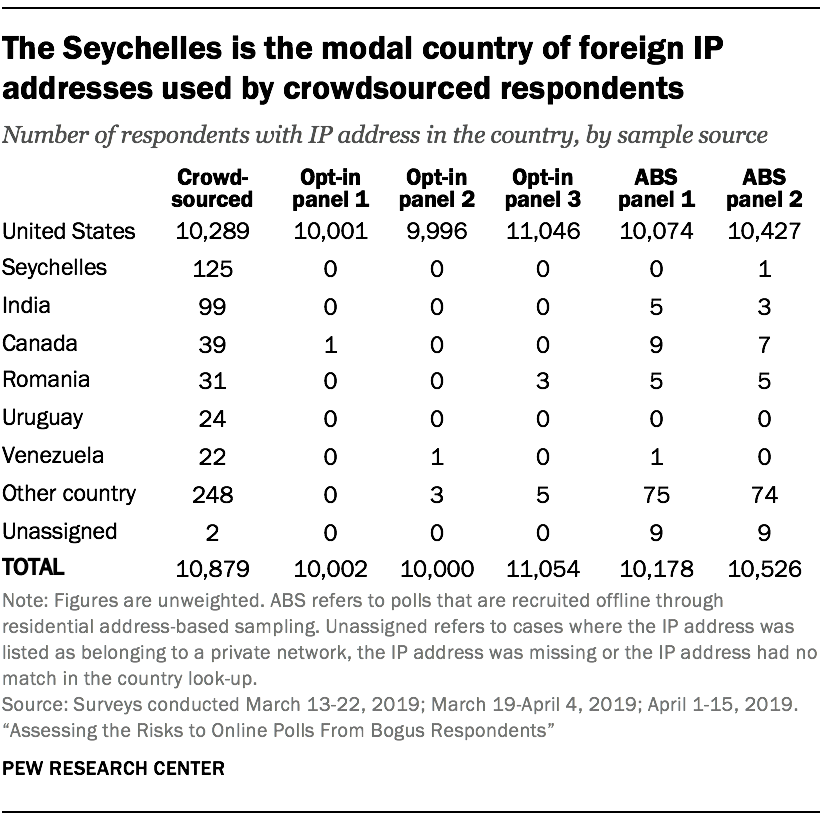

Among the address-based respondents, 1% had a non-U.S. IP address, which compared to 5% of the crowdsourced respondents.16 The latter result is almost identical to the non-U.S. rate found by Ahler and colleagues (6%) when examining IP addresses from a crowdsourced sample. In the opt-in survey panels, there were a few respondents with a non-U.S. IP address, but their share of all interviews round to 0%. This suggests that the opt-in panels may have controls in place to guard against this. In fact, several prominent online opt-in survey panels mention in their online information that they use ReleventID, which uses IP geolocation as one of the criteria for identifying fraudulent respondents.

Among the foreign IP addresses in the address-recruited panels, Canada and Mexico were the most common host countries. The other foreign IP addresses came from a very dispersed set of countries.

For crowdsourced samples, prior research found that participants with a foreign IP address were particularly likely to come from India or Venezuela. The Center study found a somewhat different pattern. The most common source country for IP addresses outside the U.S. was the Seychelles (125 cases). India was the second most common (99 cases). Then there was a sizable gap before the third most common, Canada (39 cases).

The Seychelles result is particularly curious. With a total population of about 95,000, this archipelago off the coast of Africa is more likely to be home to servers or networks masking foreign respondents’ location as opposed to the home of the actual participants. Notably, this particular data center is known to be used by software companies whose products are aimed at masking an internet user’s identity and location.

While we cannot know for certain where the users of these services are physically located, an earlier study by TurkPrime (2018) found that 89% of participants with IP addresses associated with these kinds of data centers were located in India.17

The fact that a crowdsourced interview was traced back to a data center does not necessarily imply that the response is bogus as some portion of the U.S. adult population use these kinds of online privacy services legitimately. However, while IP addresses originating from data centers made up 2% of completes among the address-recruited samples, they comprised 8% of the crowdsourced interviews. For all three opt-in panels, addresses originating from data centers made up less than one percent of completed interviews, a pattern suggestive of screening on the part of the opt-in sample providers.

Duplicate IP addresses more common in crowdsourced poll

IP address data can also help detect instances where a given person may have answered the survey more than once. As with foreign geolocation, however, duplicate IP addresses sometimes have a benign explanation (e.g., internet service provider assigned multiple customers the same IP address). So while a duplicate IP is suspicious and may signal a fraudulent interview, it is not dispositive. Some very low-level duplicate rate could be expected just based on benign factors.

In total, 2% of the study interviews came from an IP address that appears in the dataset more than once. The rate among crowdsourced respondents was 5%, which is identical to the rate found by Ahler and colleagues (2019) for crowdsourced respondents. Among the opt-in recruited survey panels in this study, the rate of duplicate IP addresses ranged from 0% (opt-in panel 3) to 3% (opt-in panel 1). In both address-recruited panels, the rate was 1%. Duplicates were more common among foreign IP addresses than domestic ones (12% and 2%, respectively), but most duplicates (92%) were domestic IP addresses.

On balance these data show that the incidence of suspicious IP attributes – the IP address being a duplicate or based in another country – was much greater in an online crowdsourced sample than opt-in recruited or address-recruited panel samples. The opt-in survey panels appear to have controls in place to preclude responses from foreign IP addresses or duplicate IP addresses.