The business benefits of consolidation are clear and unmistakable. Stations save on overhead by combining back office operations, including sales and engineering. They often move in together, cutting costs by sharing office and studio space. In Columbus, Ohio, for example, Sinclair’s ABC affiliate, WSYX, is housed in the same building as the Fox affiliate, WTTE, owned by Cunningham but operated by Sinclair. The ABC and Fox affiliates in Springfield, Mass., owned by Gormally Broadcasting, share studios and live-broadcast trucks, branded with both stations’ logos.

[of the]

Bigger companies also have more clout to negotiate programming deals with networks or syndicators. “If you wanted a decent seat at the table talking to those guys, you had to have scale,” said Barry Lucas, senior vice president of research at the investment firm Gabelli & Co. “Otherwise you were irrelevant and got pushed around.”1

Station groups with the advantage of size have been pushing back, more than willing to let their stations go dark on distribution systems to press for higher fees, as CBS and Media General did in 2013. CBS reportedly won a 150% fee hike from Time Warner Cable to nearly $2 per subscriber in New York, Los Angeles and Dallas, more than double the industry average.2

The explosive growth of retransmission revenue was on display at the UBS conference late in 2013 as station group executives rolled out the numbers. Meredith Corp., which owns 13 local stations, reported that retransmission dollars had more than tripled in the last three years. Scripps CEO Rich Boehne said the fees had jumped from $11.7 million in 2010 to $42 million in 2013. Media General CEO George Mahoney said his company had enjoyed roughly a six-fold increase in retransmission revenue in four years—from about $12 million in 2008 to nearly $70 million in 2012.

Stations keep only about half of that revenue–the rest goes to the networks in reverse compensation3–but the end result for station owners has been a substantial increase in the value of their broadcast properties.4 “They’re all saying, ‘Oh my God! Retrans is a serious amount of money,’ ” said CBS president Les Moonves. “Stations, therefore, are much more valuable than they ever were.”5

Retransmissions is only part of the reason TV stations have increased in value. Stations airing local news, whether they produce it themselves or get it from someone else, also pull in more advertising revenue. “All the money is in news,” said Meredith chief executive Stephen Lacy, whose company is looking to buy more stations and is targeting those with top-rated newscasts.6 News generates almost half the revenue for the average TV station, according to Radio Television Digital News Association research.7 Under a typical joint operating agreement, a station that provides services for another station gets to keep about a third of that channel’s advertising revenue.8

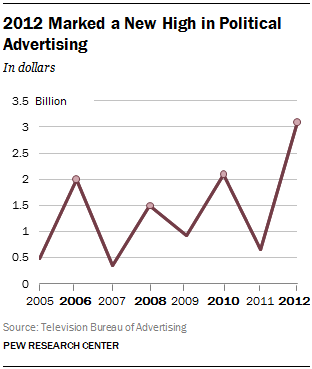

The potential for significantly higher ad revenue in election years also boosted stations’ value. In the 2012 presidential campaign–the first one conducted after the Supreme Court’s landmark 2010 Citizens United ruling –a record $3.1 billion in political ad revenue was spent in local television and many companies have reported huge increases in political ad revenue from the 2008 to the 2012 presidential cycles. At Scripps, for example, that revenue went from $41 million in 2008 to $107 million four years later, although at least some of that increase is due to Scripps’ purchase of more TV stations.

As a result, broadcasters are looking to buy stations in politically competitive states. Nexstar cited “political advertising activity” as a major reason it bought two Citadel stations in Des Moines and Sioux City, Iowa—a crucial caucus state where presidential campaigns spend millions on TV ads.9 It picked up two more Iowa stations in a separate deal.10

Wall Street’s response to consolidation and the growth in retransmission fees has been to push broadcast stock prices considerably higher. Nexstar’s stock value more than tripled in 2013, while Sinclair’s more than doubled. Gannett’s stock price jumped 34% the day it announced it was buying Belo.11 “The broadcasting industry has developed a reputation for being a great generator of cash,” said Michael Alcamo, president of investment banking firm M.C. Alcamo & Co.12

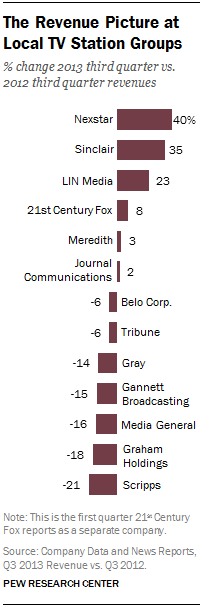

Expanding companies like Nexstar and Sinclair also reported sharply higher third-quarter revenue in 2013, bucking the expected trend of lower broadcast revenue in years without elections or Olympic Games to drive ad spending. Nexstar revenue was up 40%; Sinclair’s up almost 35%. With the exception of LIN Media, which also posted a double-digit gain, other broadcast groups reported losses or single-digit gains. The revenue from newly acquired stations accounted for most of the gains, but Sinclair said its revenues from stations it already owned were up 11% year over year, thanks to higher retransmission fees.13

Consolidation may be good for broadcast companies, but the cable companies that negotiate with broadcasters over the growing retransmission fees argue that it is bad for consumers. As large-scale broadcasters secure higher retransmission fees, “consumers ultimately foot the bill in the form of higher cable rates,” said Matthew Polka, president of the American Cable Association, which represents small and medium-sized cable companies.14 A 2013 report from the Federal Communications Commission found that the average monthly bill for expanded basic cable had increased, on average, about 6% a year between 1995 and 2012.15 Currently, cable and satellite systems pay broadcasters only about 10% of what they have to give channels like HBO and Discovery, according to SNL Kagan, but the fees paid per subscriber are moving toward parity.16