With increased demands placed on home internet connections and the nation’s internet infrastructure during the pandemic, the quality and affordability of home internet connections became a focus for users on several fronts. About half of U.S. broadband users say they have struggled with their connections, and roughly three-in-ten upgraded their connections during the pandemic. Some broadband users worry about the ongoing expense of connectivity. And at a time when the internet became a platform for social, workplace, educational and commercial activity, portions of Americans also report they have difficulty independently and effectively using tech devices. This chapter covers some of the challenges people faced with connectivity and the adjustments they made during the COVID-19 outbreak.

About half of broadband users report experiencing connection issues

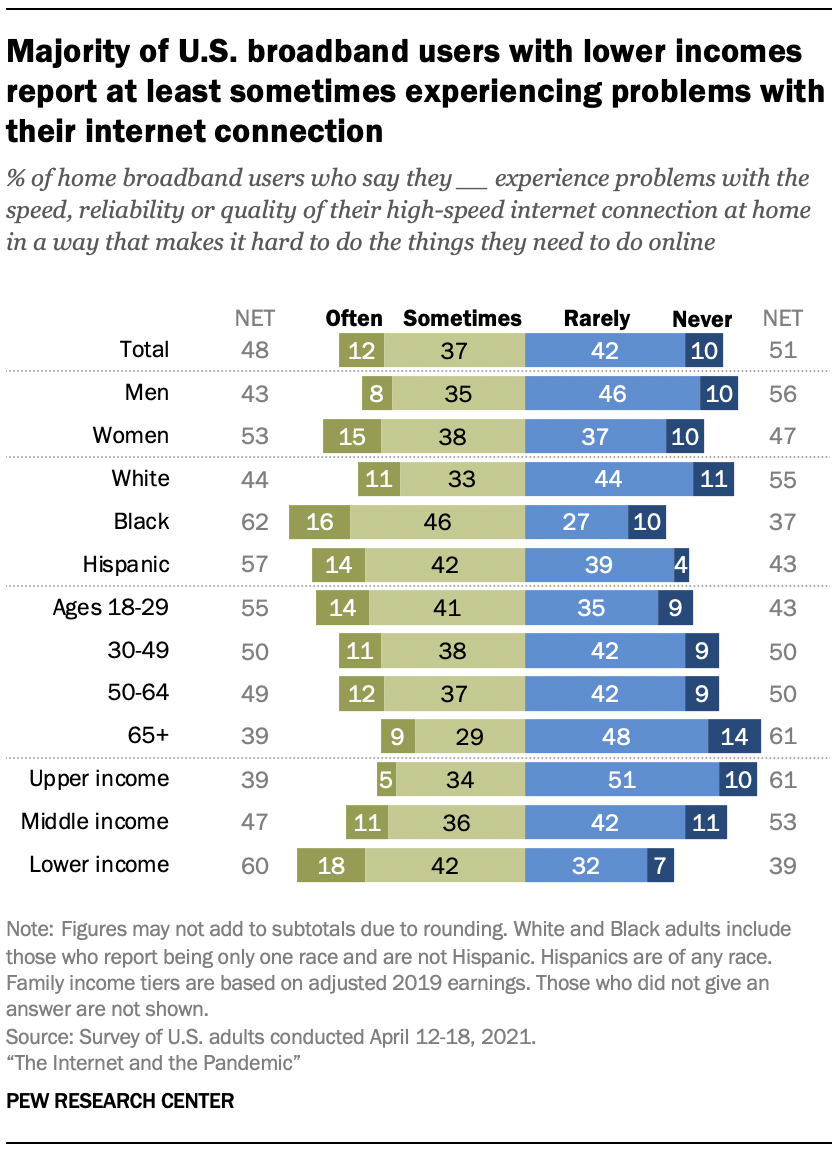

Roughly half of broadband users report they often (12%) or sometimes (37%) experience problems with the speed, reliability or quality of their high-speed internet connections at home that make it hard to do the things they need to do online. Some 51% report they rarely or never have such issues.

These connectivity issues are felt more acutely for certain users – particularly those with lower incomes, Black adults and Hispanic adults. Black and Hispanic broadband users are more likely than White users to say they experience problems with the speed, reliability or quality of their high-speed internet connection at home in a way that makes it hard to do things online. And there are sizable gaps based on income. About four-in-ten broadband users in the upper-income tier report connection issues, while 60% of users with lower household incomes say the same.

Age is also a factor: 51% of broadband users ages 18 to 64 report often or sometimes having connection issues that make it difficult to do online tasks, compared with 39% of those ages 65 and older.

Some home broadband users improved their connectivity during the pandemic

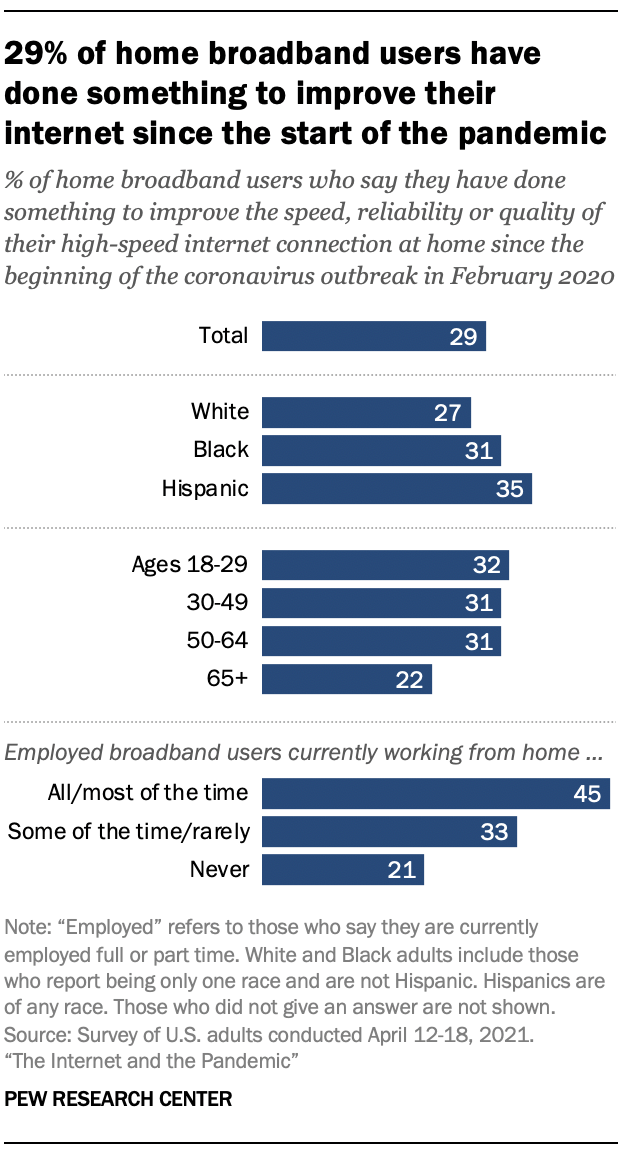

Since the start of the pandemic in February 2020, 29% of broadband users say they have done something to improve the speed, reliability or quality of their high-speed internet connection at home.

While a majority of broadband users across demographic groups did not change anything about their home internet during the pandemic, several groups stood out as being more likely to have upgraded their connection in some way.

Some 35% of Hispanic broadband users report having done something to improve the speed, reliability or quality of their high-speed internet connection at home at some point during the pandemic, compared with 27% of White broadband users. (Black broadband users do not significantly differ from White or Hispanic users in having upgraded their connection.) At the same time, users ages 18 to 64 were more likely than those ages 65 and up to say they had upgraded their home internet during this time.

Beyond differences by age or race and ethnicity, users’ experiences with upgrading their broadband connection also differ by telework status. Broadband users who work from home all or most of the time are about twice as likely as employed users who never work from home to have tried to improve their home internet connection, while a third of those who work from home some of the time or rarely say the same.

Approximately two-thirds (64%) of broadband users who have upgraded their internet say they at least sometimes experience connection issues. By comparison, 42% of users who have not upgraded their connection say they experience connection issues at least sometimes.

Roughly a quarter of tech users are worried about paying their home broadband, cellphone bills

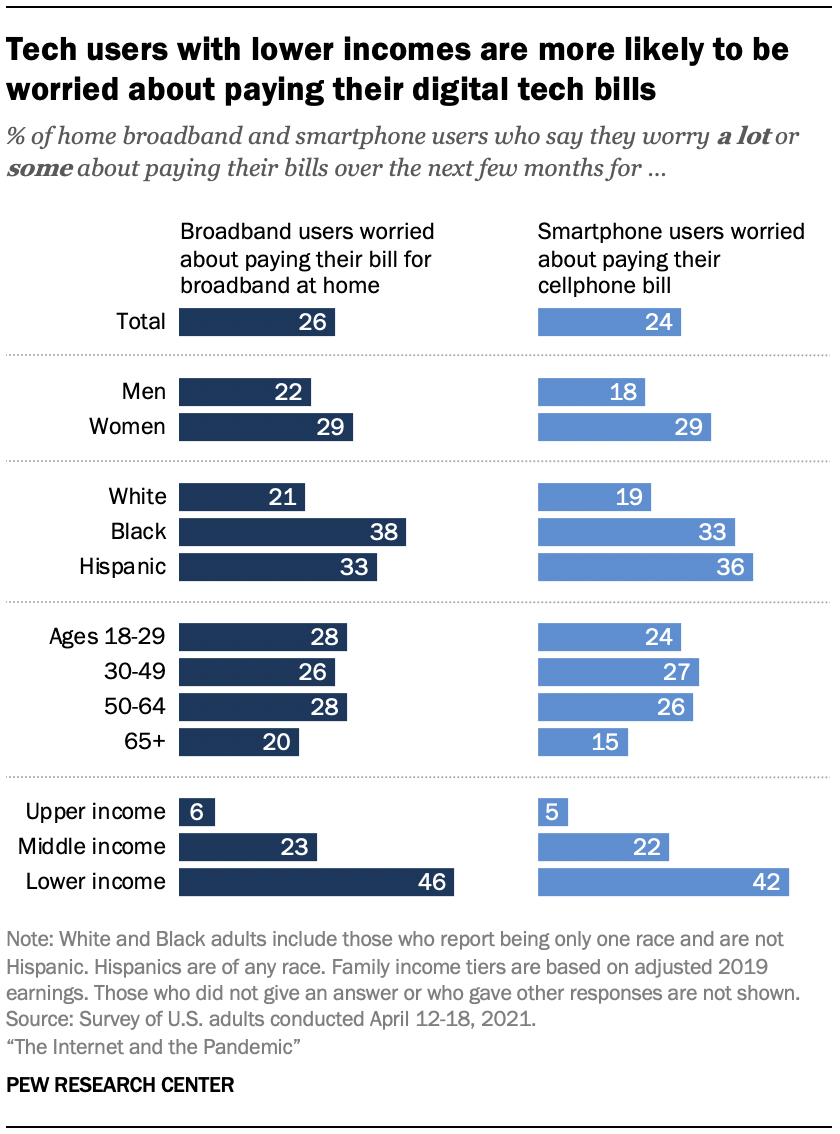

While majorities of Americans use home broadband and smartphones, the cost of their bills can be prohibitive for some users. About a quarter of home broadband users (26%) say they are at least somewhat worried about affording a high-speed internet connection at home over the next few months, while a similar share of smartphone users (24%) express the same concern over their cellphone bill.

Americans with lower incomes are especially likely to express concern about broadband and cellphone bills. Some 46% of broadband users with lower household incomes say they worry a lot or some about being able to pay for their high-speed internet connection over the coming months, compared with 23% of those with incomes in the middle and just 6% of those in the high-income tier. Among smartphone owners, 42% of those who have lower incomes say they worry at least some about paying their cellphone bills, compared with 22% of those who are middle-income and just 5% of users in the upper-income tier.

There are also some differences by age. Broadband and smartphone users ages 18 to 64 are more likely than those ages 65 and older to say they worry about being able to pay their internet or cellphone bills.

The share of Hispanic users who say they are worried about paying for their tech-related bills has declined sharply in the past year. In April 2021, 33% of Hispanic broadband users said they were worried about being able to pay for their home internet services, down from 54% in April 2020 when many stay-at-home orders began in the U.S. Similarly, the share of Hispanic smartphone owners expressing worry about paying their bills declined by 20 percentage points (from 56% in 2020 to 36% in 2021).

Other Center reports have found that financial challenges have been exacerbated by the pandemic. In April 2020, about half of Americans said the coronavirus posed a major threat to their personal finances, and, as of August 2020, 42% of Americans said that someone in their household had lost their job or experienced a pay cut because of the outbreak. Previous Center studies have also found that cost concerns can be a key reason why some Americans do not subscribe to high-speed internet at home.

Majorities of Americans do not think it is the responsibility of the federal government to ensure broadband access to all during the pandemic

During the pandemic, there have been debates about the digital divide and whether the government should ensure online access to all Americans. The Biden administration has pushed to expand access to high-speed internet through internet subsidies for Americans with lower incomes in recent months. In addition, a bipartisan infrastructure spending plan includes $65 billion aimed at getting all Americans affordable broadband access.

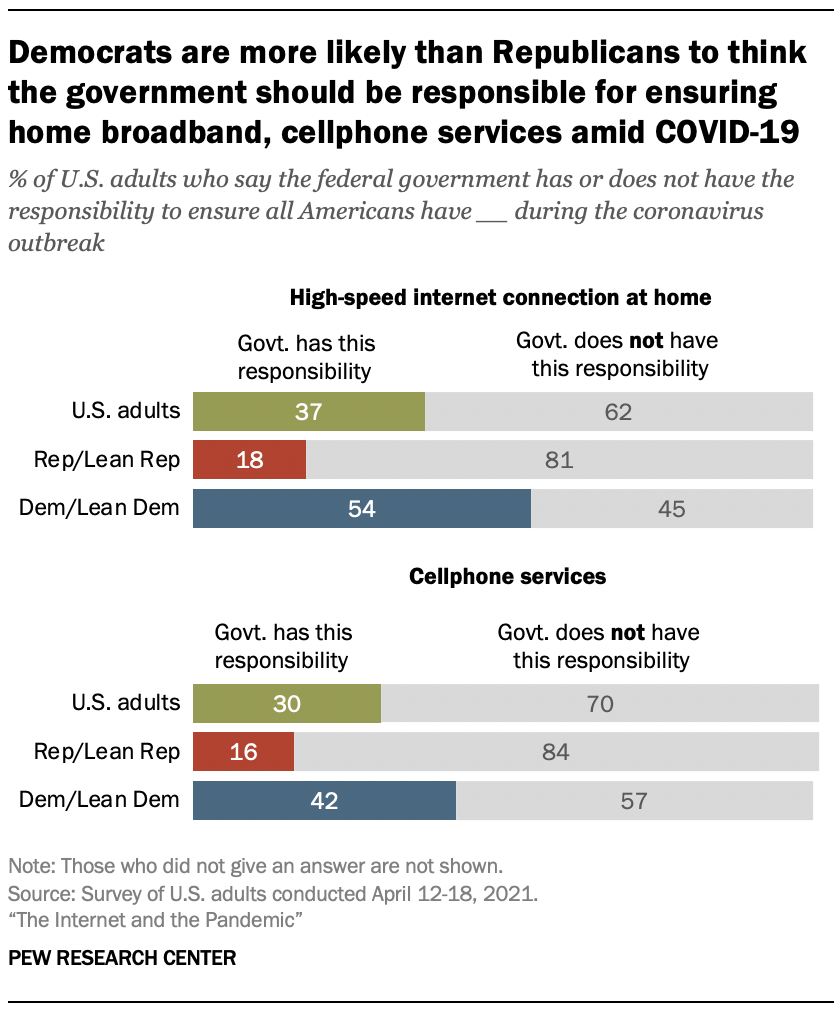

But while government efforts are underway to address these digital divides, a majority of Americans (62%) say in this survey that it is not the responsibility of the federal government to ensure that all Americans have a high-speed internet connection at home. Some 70% also say it is not the responsibility of the government to ensure cellphone service to all Americans. About four-in-ten or fewer believe the government should bear this responsibility. For example, 37% of Americans say that the government has a responsibility to ensure all Americans have high-speed internet access during the outbreak. This overall share is unchanged from April 2020 – the first time Americans were asked this specific question about the government’s responsibility during the pandemic to provide high-speed internet access.8

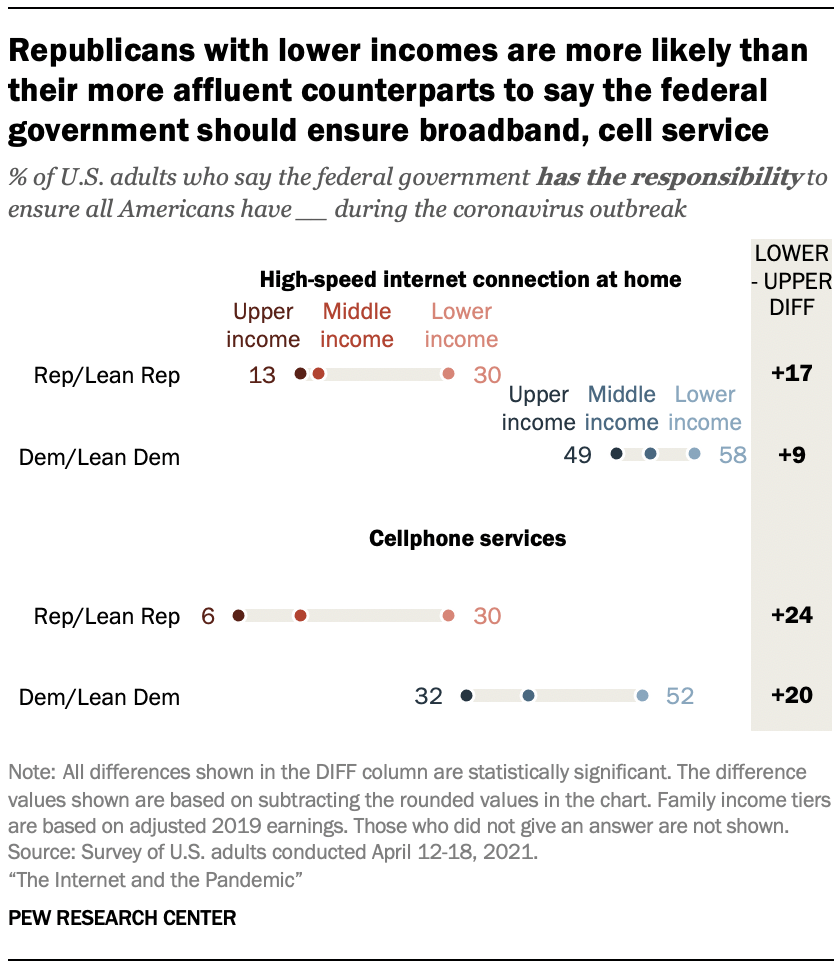

Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party are more likely than their Republican and Republican-leaning counterparts to believe that the government should have a role in ensuring these services. Some 54% of Democrats say the federal government has a responsibility to ensure that all Americans have a high-speed internet connection at home during the COVID-19 outbreak, while just 18% of Republicans hold this view. Democrats are also more than twice as likely as Republicans to believe the federal government has a responsibility to provide cellphone service for all Americans amid the outbreak (42% vs. 16%).

While a similar partisan pattern was seen in April 2020 when the Center last surveyed on this topic, the shares of Republicans saying the government has a responsibility during the pandemic to ensure high-speed internet access (a 4 percentage point dip) and cellphone services (5-point dip) have declined slightly over the past year.

On these issues, there are differences within the Republican Party by income. Among Republicans and Republican leaners, 30% of those with lower incomes say the federal government has a responsibility to ensure that all Americans have a high-speed internet connection at home during this pandemic, compared with 15% of those in the middle-income tier and 13% of those who are in the upper-income tier. When asked about their views about ensuring cellphone services, 30% of Republicans with lower incomes say that the government bears this responsibility, while smaller shares of middle- and upper-income Republicans say this (13% and 6%, respectively). Similar differences by income are seen among Democrats.

Broadband users who express concern about paying their high-speed internet bills in the coming months are more likely than those who are less worried about those bills to back the idea that the federal government should ensure high-speed internet access during the coronavirus outbreak (49% vs. 33%). Similarly, smartphone users who say they worry about affording their cellphone bills for the next few months are more likely than those who are less worried about their phone bills to say that they think the federal government has a responsibility to ensure that all Americans have cellphone service during the coronavirus (41% vs. 26%).

Older Americans are particularly likely to express concern about their ability to independently and effectively use technological devices

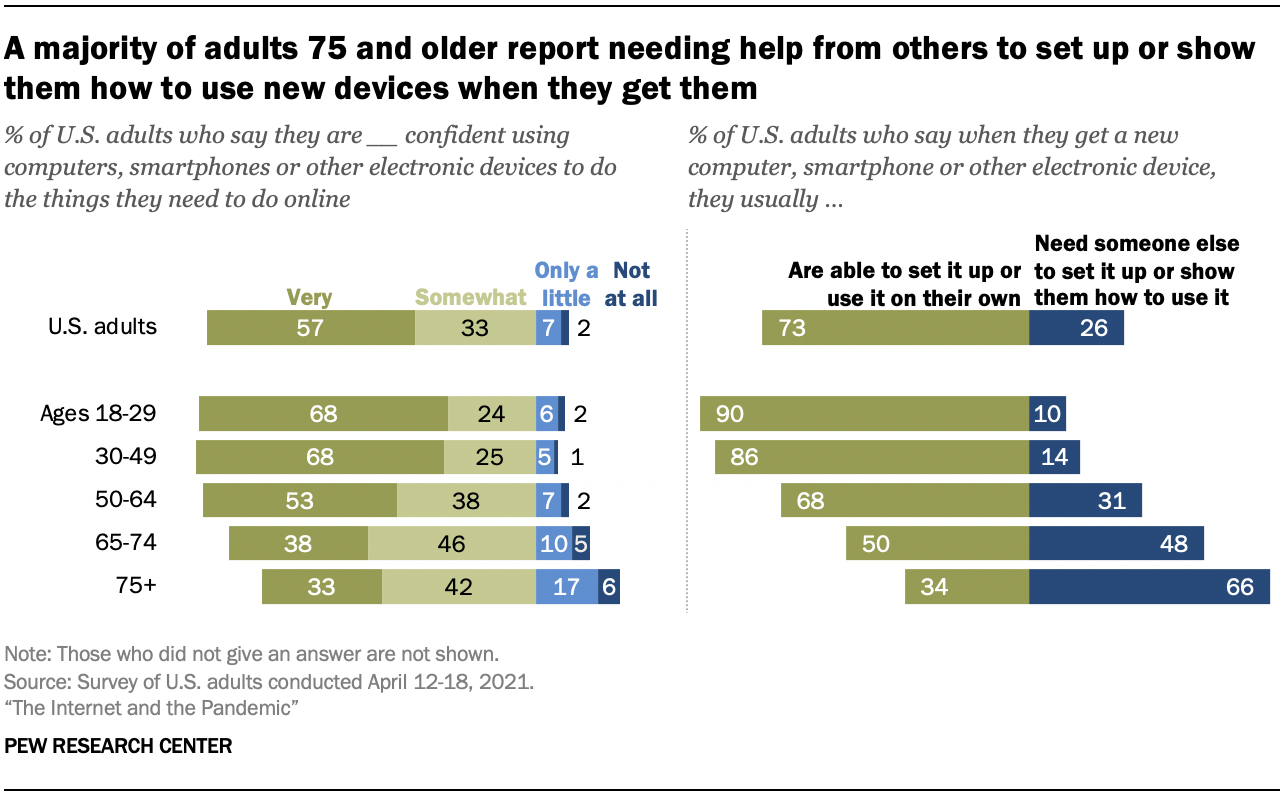

Another challenge Americans may face in navigating the digital landscape is how comfortable they are using technology, especially new kinds of tech tools. Some 26% of U.S. adults report that when they get a new computer, smartphone or other electronic device, they usually need someone else to set it up or show them how to use it. Some 10% say they are not at all or only a little confident using computers, smartphones or other electronic devices to do the things they need to do online.

Adults 75 and older stand out as particularly likely to say they need help with new devices: 66% of those in this group say that when they get a new computer, smartphone, or other electronic device, they usually need help to set up, compared with 48% of those ages 65 to 74, 31% of those 50 to 64 and just 12% of adults under 50. While majorities across age groups say they are confident in their ability to use devices to do the things they need to do online, adults 65 and older are less likely than their younger counterparts to say they are confident.

These two challenges are interrelated. For example, 77% of Americans who are at least somewhat confident they can use technological devices effectively report that they can set up or use new devices on their own. Similarly, about six-in-ten adults who are not confident in their abilities to use their devices effectively (57%) say they need someone else to set up or show them how to use new devices.

30% of adults have lower ‘tech readiness’; they have had different experiences with the internet than others during the pandemic

As some Americans suddenly shifted to deeper reliance on technology during the pandemic, new questions related to digital divides surfaced around ability to use the technology. Would all Americans – especially those, like older adults, who are less likely to be tech-savvy – be able to navigate an increasingly virtual world confidently, independently and successfully?

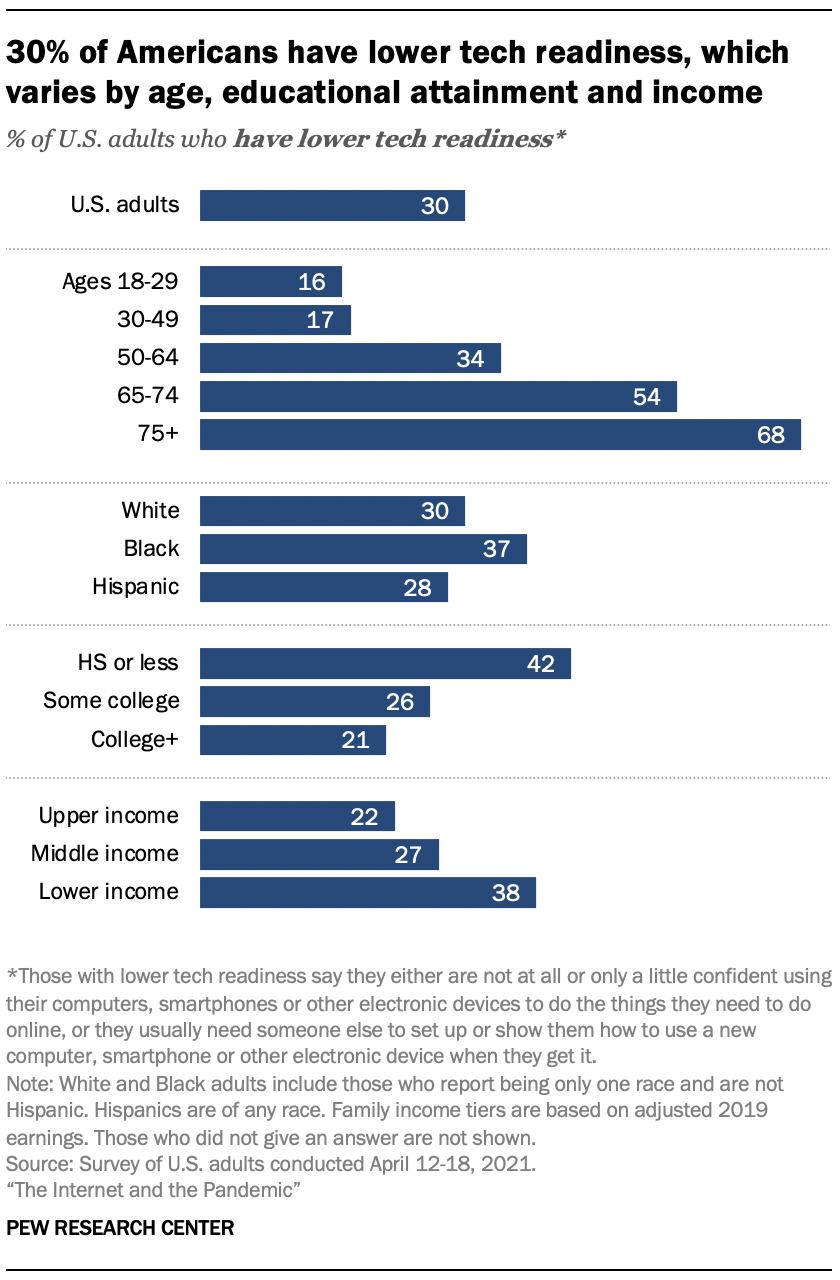

The April survey reveals how a subset of Americans who may have been less prepared to effectively use technology navigated the digital environment of the pandemic. As discussed above, 26% of adults say they usually need someone else to set up a new digital device or show them how to use it, and 10% say they are not at all or only a little confident using digital devices to do the things they need to do online. In total, some 30% of Americans say either of these things, and 5% say both. Throughout this chapter the 30% meeting at least one of the two criteria are referred to as having “lower tech readiness.”

Determining tech readiness

The terms “lower tech readiness” and “higher tech readiness” are used throughout this chapter to describe two groups who may face different challenges in using technology. Americans were asked two questions relating to the concept. One was: “Overall, how confident, if at all, do you feel using computers, smartphones, or other electronic devices to do the things you need to do online?”

The other asked people to choose the answer that best describes them: “When I get a new computer, smartphone, or other electronic device, I usually need someone else to set it up or show me how to use it” or “I usually am able to set it up and learn how to use it on my own.”

“Lower tech readiness” describes people who say either they are not at all or only a little confident using their digital devices to do the things they need to do online, or they usually need someone else to set up or show them how to use new devices. Some 30% of U.S. adults are characterized in this way.

“Higher tech readiness” describes a person who says both they are very or somewhat confident using their digital devices to do the things they need to do online and they are usually able to set up and learn how to use a new device on their own. Some 69% of U.S. adults fall in this group.

It is important to keep in mind that there are many factors that may contribute to “tech readiness.” The Center has previously studied the digital divides stemming from differences in access to the internet and device ownership, Americans’ problems connecting to the internet and their knowledge of digital topics. Another Center study investigated five potential elements of “digital readiness” in 2016.9

In the April 2021 survey, older adults stand out in their lower tech readiness. Roughly two-thirds of Americans 75 and older fall into this category by meeting either criteria – and about a fifth of adults 75 and older (22%) meet both of the criteria.

Beyond age, there are other differences in who has lower tech readiness. Those with lower incomes and less formal education are more likely to fall in this group this than are those with higher incomes and more formal education. And Black adults are somewhat more likely than White or Hispanic adults to fall into this lower-readiness category.

A note on tech readiness estimates

Americans’ abilities and confidence in using technology are challenging concepts to measure with today’s survey tools. Like most of the Center’s public opinion polls, this survey was conducted online. In general, online surveys tend to overestimate technology use because they contain too few adults who use the internet infrequently or not at all relative to the actual population.

This survey has several features designed to guard against this inherent tendency to overrepresent more tech-savvy adults. When respondents for this survey (fielded on the American Trends Panel or ATP) were recruited, both online and offline adults were provided a path to participate. Pew Research Center provides adults without home internet a tablet, data plan and IT support free of charge so that they can participate in the ATP. This issue is also addressed in the survey weights. Weighting helps to make a survey nationally representative with respect to key variables like age, gender, race, education and so forth. In addition to demographics, this survey’s weights make the sample more representative with respect to frequency of internet use. Our internet frequency benchmarks come from the Center’s National Public Opinion Reference Survey, which allows people to respond offline through the mail. This weighting adjustment reduces the influence of high-frequency internet users and increases the influence of low-frequency users.

Features like these distinguish Pew Research Center surveys from other surveys that simply ignore the offline population. But despite these steps, the estimates in this survey may still overrepresent adults with higher levels of ability and confidence in using technology. For example, the report’s finding that 30% of U.S. adults have “lower tech readiness” should be viewed as a lower bound on the actual population figure that might be measured with a study using additional modes, such as face-to-face interviewing. In short, while this report presents what we believe to be sound, reasonably accurate data, it is important to keep in mind the limitations of even rigorous online surveys for measuring these particular constructs.

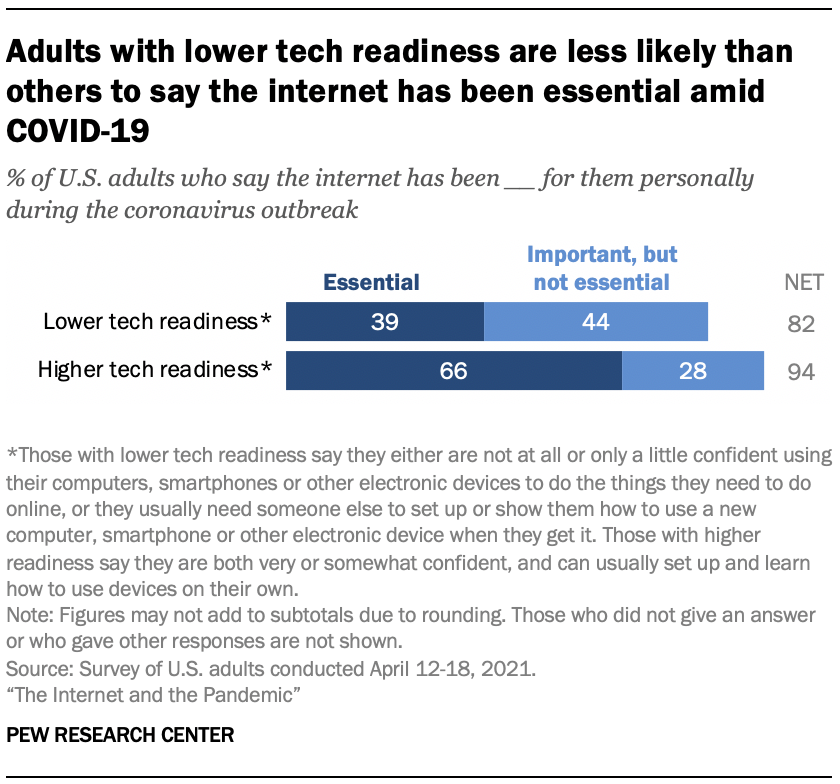

These readiness groups have different views of how personally important the internet has been amid the pandemic: The share of Americans with lower tech readiness who say the internet has been essential to them is 27 percentage points lower than for those with higher tech readiness.

Across age groups, those with lower tech readiness are less likely than others to deem the internet personally essential during the pandemic. The gap is especially pronounced for those ages 18 to 49 (47% lower vs. 73% higher) and 50 to 64 (39% vs. 56%), while it is 12 points for those 65 and older (33% vs. 45%).10

Still, the vast majority of those reporting lower tech readiness say the internet has been at least important for them personally in the pandemic. Fully 82% of those with lower tech readiness and 94% of those with higher tech readiness say this. Even among those 65 and older who have lower tech readiness, 82% say the internet has been at least important to them during the pandemic.

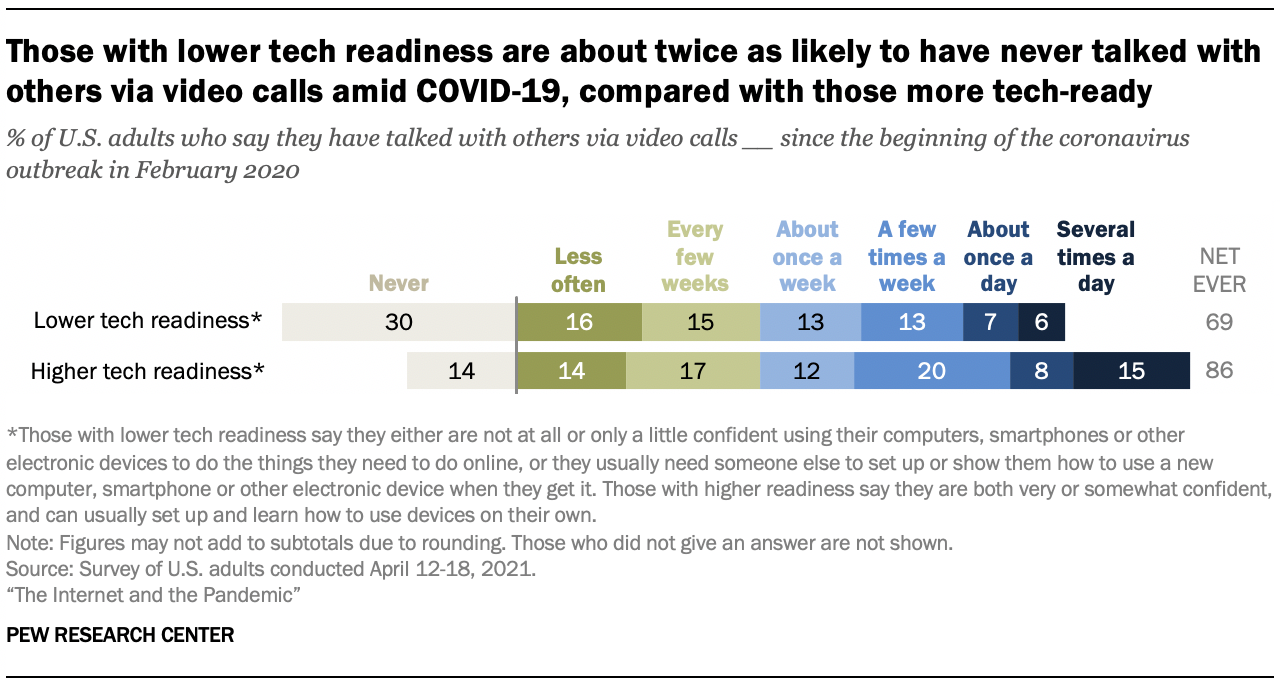

Americans with lower tech readiness are also about twice as likely as others to say they have never talked with others via video calls during the pandemic (30% vs. 14%). For those 65 and older, tech readiness relates to use of video calling in a particularly notable way. The share of Americans 65 and older with lower readiness who have used video calling in the pandemic is 21 points lower than the share of those with higher readiness (55% vs. 76%). There is a smaller but significant gap for those ages 50 to 64 (9 points). But tech readiness matters little for this among those ages 18 to 49.

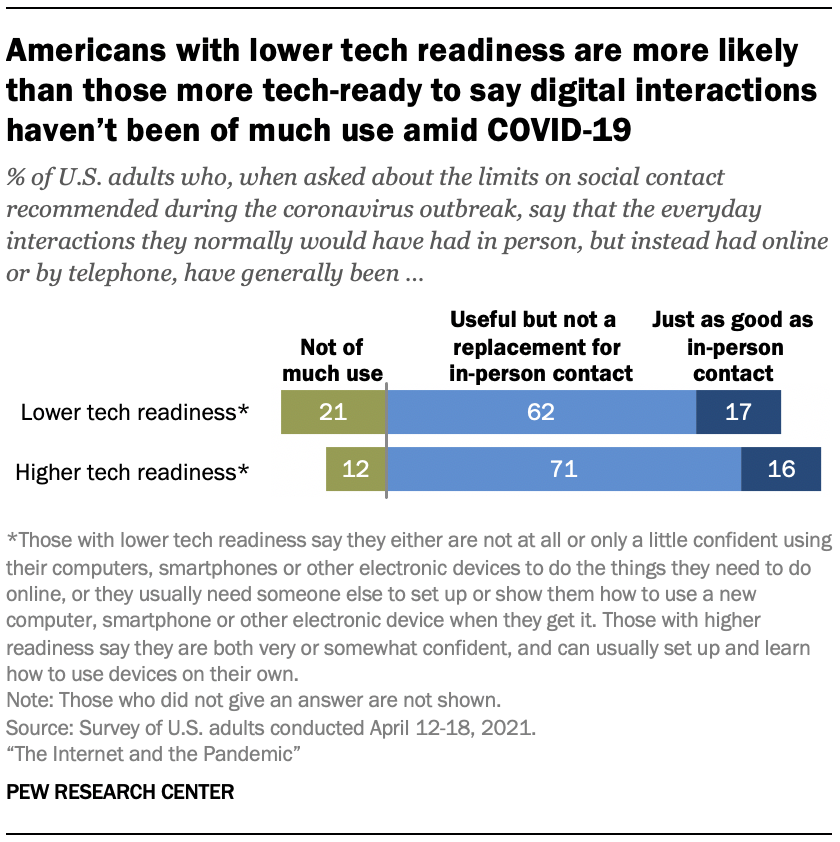

Additionally, those with lower tech readiness are more likely than others to say their digital interactions online or by phone have not been of much use. About a fifth of those who have lower tech readiness say so, compared with 12% of those who are higher in this domain. When asked about using tech in new or different ways during the pandemic, those with lower tech readiness are less likely than others to say they’ve done so (34% vs. 43%).

The role of tech readiness also is evident when it comes to the communication platforms people have used and how helpful they have been. Those with lower tech readiness are more likely than others to say that email has helped a lot in staying in touch with family and friends (24% vs. 17%). They are less likely than others to say the same about text messages or messaging apps (39% vs. 46%) or video calls (25% vs. 31%).

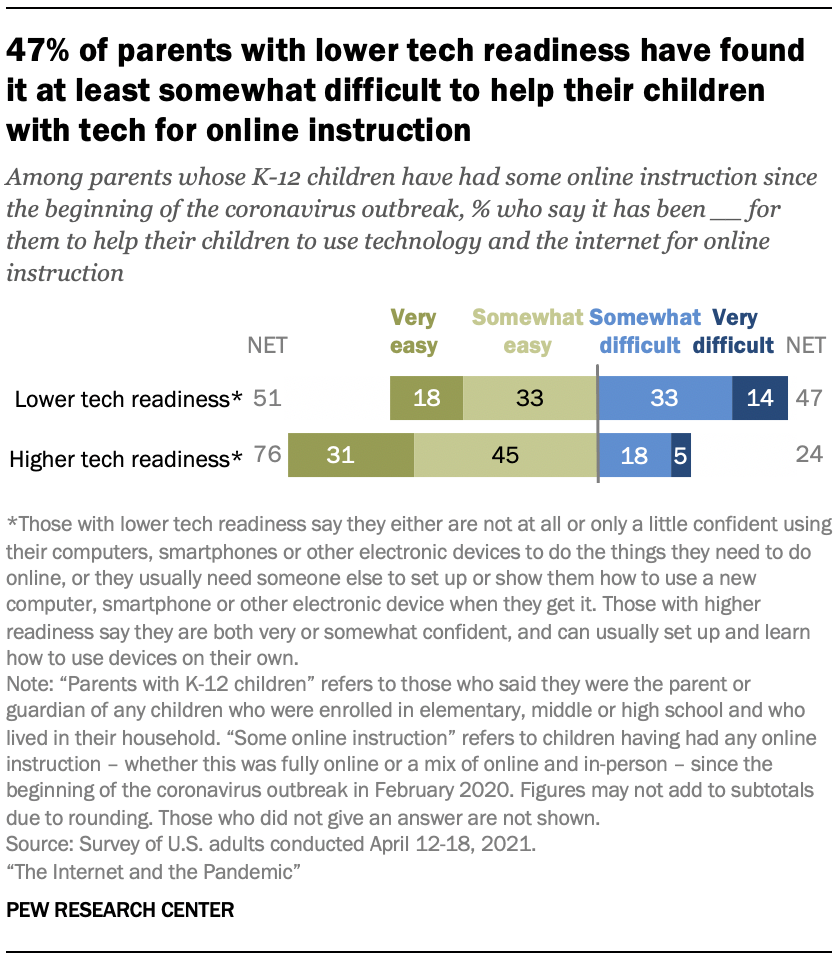

Finally, parents with lower tech readiness are more likely to report difficulty helping their children with remote learning. Among parents whose K-12 children have had any online instruction in the pandemic, roughly half (47%) of those with lower tech readiness say it has been at least somewhat difficult to help their children use technology and the internet for this purpose. This share is about twice as large as that among parents of K-12 children with any online instruction who have higher tech readiness (24%).