Outside of the specific behaviors discussed thus far in this report, online harassment presents broader issues and implications for the tone and culture of interacting in the digital age. Most Americans have heard of online harassment and many consider it a major problem, but the public is more divided on foundational issues such as the appropriate balance between freedom of speech and safety online. Similarly, most agree that online companies should be held responsible for dealing with harassment on their platforms, but the public also sees a role for law enforcement, elected officials and even ordinary users in addressing harassment. And while many see anonymity as a key enabler of online harassment, many Americans also see the benefits of anonymity in other contexts.

The vast majority of Americans have heard about the issue of online harassment; nearly two-thirds consider it a major problem

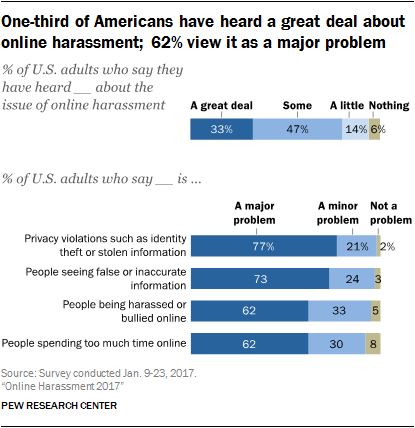

Among the public, there is widespread awareness of the issue of online harassment. Roughly one-third (33%) of Americans have heard a great deal about this issue, and fully 94% have heard at least a little about it. Awareness is high across a broad range of demographic groups, though younger adults are especially likely to have heard a great deal about it.

Along with this widespread awareness, a majority of Americans (62%) consider harassment and bullying online to be a major problem. Compared with other common problems online, that is identical to the share that thinks people spending too much time online is a major problem (62%), but somewhat smaller than the share that considers people’s exposure to false or inaccurate information (73%) or privacy violations such as identity theft (77%) to be serious issues.

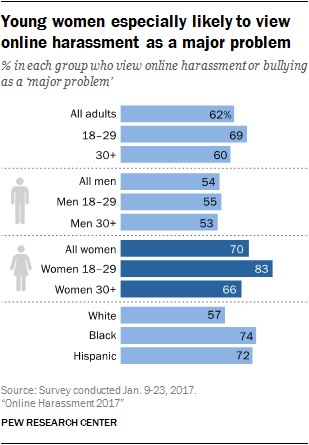

Certain groups of Americans tend to view online harassment as a more serious problem than others, with young women among the most prominent. Fully 83% of women ages 18 to 29 describe online harassment as a major problem, a substantially larger share than either men in the same age group (55%), women 30 and older (66%) or men 30 and older (53%). In fact, a larger share of young women view online harassment as a major problem than any of the other three issues measured in this survey; they are the only major demographic group for whom this is true. Broadly speaking, women are more likely than men (by a 70% to 54% margin) to say that people being harassed or bullied online is a major problem.

Americans’ views of online harassment also vary based on age and race: 18- to 29-year-olds are more likely than those 30 and older to view online harassment as a serious issue (69% vs. 60%), while blacks (74%) and Latinos (72%) are more likely to say that online harassment is a major problem compared with whites (57%).

Americans who have experienced online harassment in their own lives are more likely than those who have not been harassed to consider this a major issue – though not by an especially dramatic margin. About two-thirds (65%) of Americans who have experienced any type of online harassment describe this issue as a major problem. At the same time, online harassment is viewed as a major problem by 58% of Americans with no direct experience with this issue.

Likewise, Americans who have witnessed others being targeted with potentially harassing behavior are more likely to view it as a major issue – although again by a relatively modest margin. Roughly two-thirds (64%) of Americans who have witnessed these types of behaviors directed toward others consider online harassment or bullying to be a major problem, compared with 55% of those who have not personally witnessed harassment online.

A larger share of online adults think the internet allows people to be more anonymous than in 2014 – although that anonymity can have positive as well as negative impacts

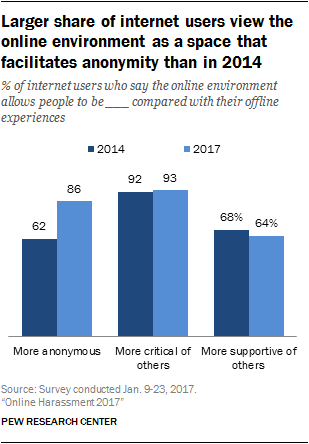

Anonymity is often blamed as a key enabler of cruelty and abuse in discussions of online harassment, and this survey finds evidence that the internet is indeed viewed as a much easier place to be anonymous than was true just three years ago. Fully 86% of internet users now say the online environment allows people to be more anonymous than is true offline – a 24-percentage-point increase from 2014, when 62% of online adults held this view. By contrast, the share of internet users who say the online environment allows people to be more critical (93%) or supportive (64%) of others is largely unchanged over the same time period.

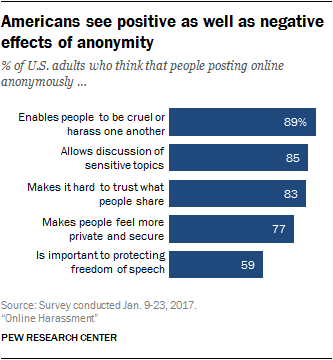

But the impression that anonymity is more widespread online is not universally viewed in a negative way: Americans see both upsides and downsides to anonymity online. On the positive side, 85% of Americans feel anonymity allows people to discuss sensitive topics freely, 77% think anonymity makes people feel more private and secure, and 59% say it is important to protecting freedom of speech. On the negative side, 89% feel that anonymity facilitates harassment and cruelty, while 83% say it makes it hard to trust what people are saying online.

In their own words: Anonymity online

“Mostly childish behavior between individuals taking advantage of the anonymity afforded by social media and online tools. One person accuses another of something and it becomes some ludicrous exchange of insults.”

“People being generally rude and feeling safe behind their keyboard.”

“Just the normal of what I call internet muscles. Talking lots of trash because you don’t know who’s saying what.”

“Usually it’s about someone’s comments online and an individual going out of their way to insult, degrade or personally attack them from a place of anonymity. Mostly it implies some sexual, mental or otherwise degrading accusation about them and has more profanity than wit.”

“Cyberbullies who are anonymous are relentless. They find a weakness and hammer it over and over.”

“Anonymous individuals using their ‘freedom of speech’ and anonymity to purposefully antagonize others, attack those with differing opinions, or merely to exercise the illusion of power over another. People commonly go far beyond what would be deemed culturally or socially acceptable in a normal interaction.”

Online platforms and digital bystanders are seen as leaders in tackling online harassment

When asked about the variety of actors that might be responsible for preventing or minimizing abuse online, the public sees two playing an especially prominent role. Almost two-thirds (64%) of Americans6 say that online services (such as social media platforms or other websites) should play a major role in addressing online harassment, while another 60% say ordinary users share in this responsibility. Outside the digital realm, smaller but still substantial proportions of Americans say that law enforcement (49%) and elected officials (32%) should play a major role in addressing online harassment.

Americans who have heard a great deal about the issue of online harassment see a more prominent role for all of these groups in combating harassment online. Compared with those who have only heard a little bit about the issue, this group is substantially more likely to see a major role for online services (81% vs. 51%), others who see harassment happen (76% vs. 48%), law enforcement (61% vs. 47%) and elected officials (46% vs. 26%).

Interestingly, even as views on this question vary significantly based on one’s familiarity with the issue of online harassment, there is not any variation based on personal experiences with harassment. Americans who have themselves experienced harassment online (even if that harassment is severe) have nearly identical views to those who have not been targeted in such a way.

In general, a majority of men and women think each of these groups should play some role in addressing online harassment; but women are somewhat more likely than men to think three of these entities should play a major role in tackling the issue. For instance, 54% of women say law enforcement should play a major role in addressing online harassment, compared with 43% of men. Women are also a bit more likely than men to say that bystanders (63% vs. 57%) and elected officials (35% vs. 29%) have a major role to play in addressing online harassment.

There are also age differences on this issue, with older adults tending to favor more involvement from traditional institutions, like the criminal justice system or elected officials. Around six-in-ten adults ages 65 and older (58%) think law enforcement should play a major role in addressing online harassment, and around four-in-ten (38%) say the same of elected officials. Those shares drop to 37% and 28%, respectively, among 18- to 29-year-olds.

Around eight-in-ten Americans think online services should be responsible for harassment that takes place on their platforms

The Communications Decency Act of 1996 provides that online hosts are not legally responsible for the content users post on their platforms. Nonetheless, this survey finds that roughly eight-in-ten U.S. adults (79%) feel that online services have a responsibility to step in when harassing behavior occurs on their sites: Just 15% say these services should not be responsible for the content users post or share on their site, even when the material is harassing.

Majorities of all major demographic groups agree that online platforms have a responsibility to confront abusive behavior on their sites, though some are more supportive of a “hands-off” approach than others. For instance, men are slightly more likely than women to feel that online services should not be held responsible for harassing behavior on their platforms (18% vs. 12%). And adults younger than 30 are more than twice as likely as those 65 and older to hold this view (19% vs. 8%).

Better policies from online platforms and stronger laws seen as most effective methods to address online harassment

When presented with a list of possible ways to address online harassment and asked to choose the one they think is most effective, just over one-third of Americans (35%) say that better policies and tools from online companies are the most effective approach. A slightly smaller share (31%) feels that stronger laws against online harassment and abuse are the most effective way to combat this behavior. Another 15% cite peer pressure from other users, while 8% select increased focus and attention from law enforcement and 5% cite some method other than the four provided in the survey.

Men and women differ in their perceptions of these solutions, particularly when it comes to the effectiveness of stronger online harassment laws. About a third of women (36%) say that stronger laws are the best way to prevent online harassment, compared with 24% of men. And young women are especially likely to say increased attention from law enforcement is the key to addressing online harassment (14% vs. 5% of young men). Meanwhile, men are somewhat more likely to say that better policies and tools from online companies are the best solution to combatting online harassment (39% vs. 31%).

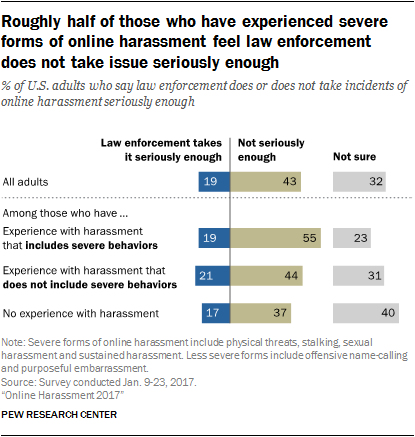

Public mixed on whether or not law enforcement takes online harassment seriously enough

In several recent cases of online harassment, the targets have expressed frustrations with the ability of law enforcement to properly address this issue, and in some instances have argued – accurately or not – that law enforcement may not take online abuse as seriously as other types of crime they patrol.

Overall, the public expresses somewhat mixed views on this subject. A plurality of U.S. adults (43%) say that law enforcement does not take incidents of online harassment seriously enough. However, 19% feel that law enforcement does take harassment complaints seriously – and 32% say they are uncertain whether or not law enforcement takes online harassment seriously enough.

Americans’ views on this subject differ by respondents’ own awareness of, and personal experiences with, abusive behavior online. Almost half (49%) of those who have experienced some type of harassing behavior – including 55% of those who have experienced severe types of harassment – feel that law enforcement does not take online harassment incidents seriously enough. But that figure falls to 37% among those who have not experienced any type of online harassment themselves.

Similarly, 58% of those who have heard a great deal about online harassment do not think law enforcement takes the issue seriously enough; that share drops to 40% among those with some familiarity with the issue and 35% among those with little familiarity.

Along with these differences, women are a bit more likely than men to say that law enforcement does not take this type of harassment seriously enough (46% vs. 39%), while men are a bit more inclined to agree that law enforcement does in fact take online harassment seriously (22% vs. 16%).

In their own words: Police and law enforcement involvement with online harassment

[I’ve seen]

“I was sent lewd photos from an anonymous person that ended up being a student at the school I work for. He was persistent, despite getting law enforcement involved. It resulted in an extreme anxiety and stress for me.”

“One individual took objection to another user’s offensive language and racist comments on a particular website. The individual objecting was threatened with bodily harm. Police needed to get involved and a restraining order was issued to keep the individual making the threats away from the individual that originally complained.”

“An individual was trying to cyberstalk another individual while online. I witnessed the action and got law enforcement involved. An arrest resulted from the action. Those of us that have been on the receiving end tend to be protective of those we see getting similar experiences.”

“When I was in my first year of college I was at a school-sponsored event and met a guy who seemed nice. We exchanged numbers, but soon he was stalking me physically as well as online. He even used the school’s computers to find out my class schedule when I hadn’t told him. Eventually I had to call the campus police as he was messaging me on social media and constantly showing up wherever I was even after I told him I wasn’t interested.”

“A friend experienced two years of online harassment and extremely embarrassing and personally damaging postings, all of which made him retire from his job and move away, and law enforcement didn’t take it seriously. He got almost no support from them.”

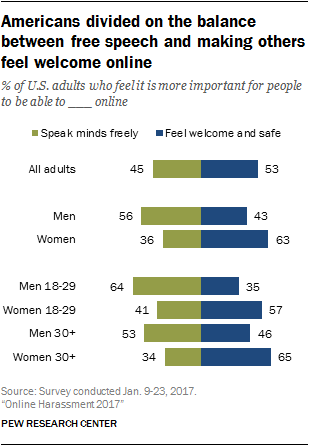

Americans are relatively divided on the appropriate balance between protecting the ability to speak freely and making people feel welcome and safe online

The debate over online harassment has long been marked by a tension between allowing people to speak freely on a wide range of issues while simultaneously maintaining a baseline level of safety online. And this survey finds that the public as a whole is divided on how to prioritize these issues. When asked which they feel is more important, 45% of Americans say it is more important that people are able to speak their minds freely online; a slightly larger share (53%) says it is more important that people are able to feel welcome and safe online.

Although the public as a whole is relatively divided on this question, certain groups feel more strongly that one of these two objectives should be given priority over the other. Most prominently, men are substantially more likely than women to say it is more important for people to be able to speak their minds freely when they are online: 56% of men choose this option, compared with 36% of women. By contrast, women are much more likely to say that people should be able to feel welcome and safe in online environments: 63% of women take this side of the debate, compared with 43% of men.

Interestingly, Americans who have themselves encountered various types of potentially harassing behaviors online – even those who have experienced relatively extreme forms of harassment – do not differ substantially from other Americans in their prioritization of these two issues. About half (52%) of Americans who have personally experienced severe forms of online harassment feel it is more important for people to be able to speak their minds freely online, slightly more than the share (46%) that feels it is more important to make people feel safe and welcome in these spaces.

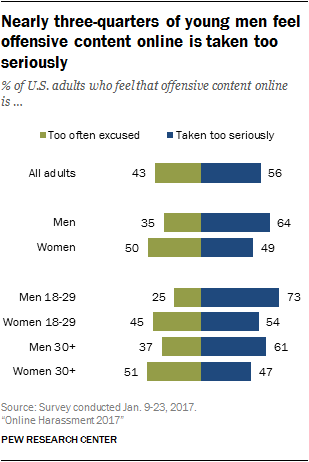

A slight majority of Americans feel that many people today take offensive content online too seriously

Another common debate around online harassment concerns the question of just how seriously users should take offensive content. When presented with two statements that might describe their views on this subject, a slight majority of Americans (56%) support this statement: “Many people take offensive content they see online too seriously.” Meanwhile, 43% agree with the statement: “Offensive content online is too often excused as not being a big deal.”

Young men are particularly likely to believe that offensive content online is taken too seriously. Fully 73% of 18- to 29-year-old men feel that too many people take offensive content online more seriously than they should, nearly three times the share that feels people make too many excuses for offensive content online (25%). Among men of all ages, 64% feel that offensive online content is taken seriously by too many people. Women, on the other hand, are much more closely split on this issue: 50% feel that too many people excuse offensive content online as not being a big deal, but 49% feel that this sort of content is generally taken too seriously.

As was true with the free speech data discussed above, Americans who have themselves experienced online harassment do not prioritize this issue in a markedly different way from the population as a whole. Even among Americans who have experienced some type of severe online harassment, 60% side with the notion that many people take offensive content online too seriously (compared with 39% of the same group who feel that too many people make excuses for offensive content online).

In their own words: Is online harassment taken too seriously?

“Just trolls being trolls, nothing to worry about.”

“After expressing an opinion online, someone with a different view tried to start an argument after calling me several names. It’s pretty easy to just ignore them. Just don’t stoop to their level.”

“Cursing and name-calling in comment sections but I believe that’s part of the territory. You got to have thicker skin if you’re going to get online and don’t take everything so personally.”

“Welcome to the internet, where statements are just statements. People will always have an opposing point of view, just move on.”

“People saying they’ll ‘beat your a**’ or telling someone to ‘kill yourself.’ People calling someone a ‘f****t.’ These are the most prevalent but they are almost always posted by anonymous users that are most likely complete strangers. I don’t understand why people are so easily offended by a troll from the nether sphere. Just turn the computer off or avoid the comment section. It’s not difficult to avoid cyber bullying.”

“Like an adult, I turned off the computer and walked away. No one is forcing me to be online.”