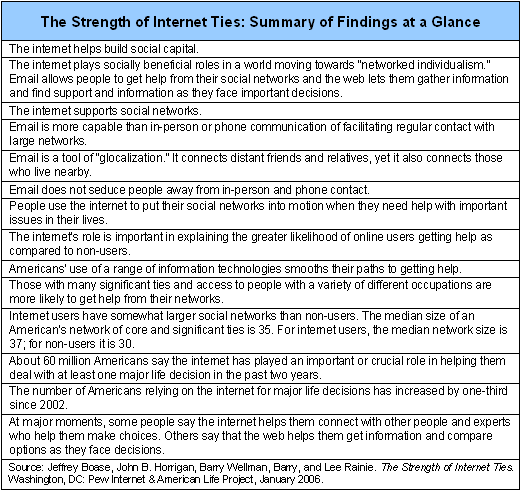

The internet helps build social capital.

This report confronts one of the great debates about the internet: What is it doing to the relationships and social capital that Americans have with friends, relatives, neighbors, and workmates? Those on one side of the debate extol the internet’s ability to expand relationships — socially and geographically. Those on the other side of the debate fear that the internet will alienate people from their richer, more authentic relations.

Once upon a time, the internet was seen as something special, available only to wizards and geeks. Now it has become part of everyday life. People routinely integrate it into the ways in which they communicate with each other, moving between phone, computer, and in-person encounters.

Our evidence calls into question fears that social relationships — and community — are fading away in America. Instead of disappearing, people’s communities are transforming: The traditional human orientation to neighborhood- and village-based groups is moving towards communities that are oriented around geographically dispersed social networks. People communicate and maneuver in these networks rather than being bound up in one solitary community. Yet people’s networks continue to have substantial numbers of relatives and neighbors — the traditional bases of community — as well as friends and workmates.

The internet and email play an important role in maintaining these dispersed social networks. Rather than conflicting with people’s community ties, we find that the internet fits seamlessly with in-person and phone encounters. With the help of the internet, people are able to maintain active contact with sizable social networks, even though many of the people in those networks do not live nearby. Moreover, there is media multiplexity: The more that people see each other in person and talk on the phone, the more they use the internet. The connectedness that the internet and other media foster within social networks has real payoffs: People use the internet to seek out others in their networks of contacts when they need help.

Because individuals — rather than households — are separately connected, the internet and the cell phone have transformed communication from house-to-house to person-to-person. This creates a new basis for community that author Barry Wellman has called “networked individualism”: Rather than relying on a single community for social capital, individuals often must actively seek out a variety of appropriate people and resources for different situations.

The internet plays socially beneficial roles in a world moving towards “networked individualism.” Email allows people to get help from their social networks and the web lets them gather information and find support and information as they face important decisions.

While traditional means of communications such as in-person visits and landline telephone conversations are the primary ways by which people keep up with those in their social networks, our research shows that email helps people cultivate social networks. We find that email supplements, rather than replaces, the communication people have with people who are very close to them — as well as those with those not so close. Email is especially important to those who have large social networks.

In a social environment based on networked individualism, the internet’s capacity to help maintain and cultivate social networks has real payoffs. Our work shows that internet use provides online Americans a path to resources, such as access to people who may have the right information to help deal with a health or medical issue or to confront a financial issue. Sometimes this assistance comes from a close friend or family member. Sometimes this assistance comes from a person more socially distant, but made close by email in a time of need. The result is that people not only socialize online, but they also incorporate the internet into seeking information, exchanging advice, and making decisions.

The internet promotes “networked individualism” by allowing people to seek out a variety of appropriate people and resources.

The internet has fostered transformation in community from densely knit villages and neighborhoods to more sparsely knit social networks. Because individuals — rather than households — are separately connected, the internet and the cell phone have transformed communication from house to house to person to person. There is “networked individualism”: Rather than relying on a single community for social capital, individuals often must actively seek out a variety of appropriate people and resources for different situations.

The internet supports social networks.

This report is built primarily around findings of a survey conducted in February 2004 that we call the Social Ties survey. It focused on the nature and scope of people’s social networks, how they use their social networks to get help, and how they use information and communication technology.

The Social Ties survey asked about two types of connections people have in their social networks:

- Core Ties: These are the people in Americans’ social networks with whom they have very close relationships — the people to whom Americans turn to discuss important matters, with whom they are in frequent contact, or from whom they seek help. This approach captures three key dimensions of relationship strength — emotional intimacy, contact, and the availability of social network capital.

- Significant Ties: These are the people outside that ring of “core ties” in Americans’ social networks, who are somewhat closely connected. They are the ones with whom Americans to a lesser extent discuss important matters, are in less frequent contact, and are less apt to seek help. They may do some or all of these things, but to a lesser extent. Nevertheless, although significant ties are weaker than core ties, they are more than acquaintances, and they can become important players at times as people access their networks to get help or advice.

Americans connect with their core and significant ties in a variety of ways. They continue to use in-person encounters and landline telephones. Yet new communication technologies — email, cell phones, and instant messaging (IM) — now play important roles in connecting network members. The internet does not stand alone but as part of an overall communication system in which people use many means to communicate.

Email is more capable than in-person or phone communication of facilitating regular contact with large networks.

As the size of a person’s social network increases, it becomes more difficult for people to contact a large percentage of network members. This makes intuitive sense. If you have 50 people in your social network, it will take a fair amount of effort to contact 25 of them regularly by using the telephone. If your social network is 20 people in size, it will take less effort to contact 15 of them regularly. Even though there are fewer people contacted, they are a greater percentage of your network.

This pattern — the percentage of one’s social network contacted declining as network size grows — holds true for almost all forms of contact analyzed in the Social Ties survey. The one exception is email. As the size of people’s social network increases, the percentage of one’s social network contacted weekly by email does not decline but remains about the same at about 20% of core and significant ties.

Several qualities of email help make sense of these findings. Email enables people to maintain more relationships easily because of its convenience as a communication tool and the control it gives in managing communication. Email’s asynchronous nature — the ability for people to carry on conversations at different times and at their leisure — makes it possible for a quick note to an associate, whether it is about important news or seeking advice on an important decision. Moreover, it is almost as easy to email a message to many people as it is to email to only one.

Email is a tool of “glocalization.” It connects distant friends and relatives, yet it also connects those who live nearby.

Email has been celebrated from the outset for its ability to connect with people around the world quickly and cheaply. This is no figment of global village hyperbole. Email is especially used for contacting distant friends and relatives. But the data also show that email is frequently used to contact those who live nearby.

Email does not seduce people away from in-person and phone contact.

Contrary to fears that email would reduce other forms of contact, there is “media multiplexity”: The more contact by email, the more in-person and phone contact. As a result, Americans are probably more in contact with members of their communities and social networks than before the advent of the internet.

- People who email the vast majority (80%–100%) of their core ties weekly are in phone contact with 25% more of their core ties than non-emailers. Moreover, those who email the vast majority of their significant ties weekly are in phone contact with twice as many of their significant ties than non-emailers.

- The patterns are somewhat different for in-person contact. Those who email the vast majority of their core ties weekly see the same percentage of their core ties weekly as do non-emailers. However, those who email the vast majority of their significant ties weekly do see 50% more of their significant ties weekly than non-emailers.

People use the internet to put their social networks into motion when they need help with important issues in their lives.

The February 2004 Social Ties survey asked respondents whether they have sought help from people in their social networks pertaining to eight specific key issues in their lives. The eight issues are:

- Caring for someone with a major illness or medical condition

- Looking for information about a major illness or medical condition

- Making a major investment or financial decision

- Finding a new place to live

- Changing jobs

- Buying a personal computer

- Putting up drywall in your house

- Deciding who to vote for in an election.

Most Americans (81%) have asked for help with one of these issues from at least one of their core ties, while nearly half (46%) have asked for help with one of these issues from at least one of their significant ties.

Internet users are more likely than non-users to receive help from core network members: 85% of online users have received help with at least one of the eight issues as compared with 72% of non-users. The average internet user received help on 3.1 of the eight issues from people in their core networks, compared with non-users getting help for 2.0 topics.

There is a similar pattern of internet users getting more support from significant ties, although a smaller percentage of significant ties are likely to be supportive: 49% of internet users have received help from their significant ties on at least one of the eight issues, compared with 40% of internet non-users. Significant ties are also more specialized than core ties in their support. Internet users have received help on 1.2 out of the eight issues from their significant ties as compared to 0.9 for the non-users.

The internet’s role is important in explaining the greater likelihood of online users getting help as compared to non-users.

One could easily imagine some other traits of internet users — such as, their higher income which makes it easier to afford access, their higher levels of education, their more sizable social networks, or their more robust professional networks — that would explain why they are more likely to get help. It could be that these characteristics, not their internet use, account for the differences in getting help relative to non-users. However, statistical regression analysis that disentangles these various effects shows that internet and email use each are independent factors in explaining the levels and likelihood of getting help.

Americans’ use of a range of information technologies smooths their paths to getting help.

The 2004 Social Ties survey also asked about whether respondents had used a number of different information technologies in the past month, namely email, instant messaging, a personal digital assistant (PDA), a cell phone, text messaging, and a wireless internet connection. Relatively heavy use of these information technologies is associated with greater access to help. This suggests that those who are “media multiplexers,” and not just email users, are able to mobilize their social networks through technology when they need help.

Those with many significant ties and access to people with a variety of different occupations are more likely to get help from their networks.

Network size matters when it comes to getting help. However, the number of people’s significant ties is more important than the number of their core ties. It is better to have a larger network of significant ties than a large network of core ties — at least when it comes to getting help of the sort asked about in the 2004 Social Ties survey. An important exception involves health care. Having a large number of core ties is a predictor of getting information and help with health care — two of the issues about which we asked respondents.

Knowing people across a range of different occupations is the strongest predictor of getting help. Respondents were asked if they are acquainted with people in the following occupations: lawyer, truck driver, sales/marketing manager, pharmacist, janitor/caretaker, engineer, cashier, waiter/waitress, computer programmer, or carpenter. The wider the range of occupational acquaintances people have, the greater amount of help to which they can access.

Internet users have somewhat larger social networks than non-users. The median size of an American’s network of core and significant ties is 35. For internet users, the median network size is 37; for non-users it is 30.

The 2004 Social Ties survey asked about the size of their social networks, how many people in their networks are “very close”(what we call their “core ties”) or “somewhat close”( what we call their “significant ties”). The survey’s approach was distinct in that it is among the first national surveys to measure the size of people’s social networks and distinguish between respondents’ “core” and “significant” ties. In terms of their social networks:

- Respondents reported that they have on average a mean of 23 core ties and 27 significant ties. These mean averages are influenced by a small number of people reporting a very large number of ties.

- The median number of core ties is 15. In other words, one-half of Americans have 15 or more ties. The median number of significant ties is 16. The median total number of ties (core + significant) is 35, somewhat larger than just adding together the separate medians.

- The number of core ties is about the same, regardless of whether one goes online or not. However, internet users have a slightly larger number of significant ties than non-users.

- As to connection speed, those internet users with high-speed connections at home have a slightly larger number of significant ties in comparison to dial-up users. Here, too, the number of core ties is about the same for internet users with either high-speed or dial-up connections at home.

When asked about their own assessments of the internet’s impact on the size of their social networks, internet users responded this way:

- 31% said it increased the number of their significant ties, and 2% said it decreased them.

- 30% said it increased the number of their casual acquaintances, and 2% said it decreased them.

- 28% said it increased the number of their core ties, and 1% said it decreased them.

About 60 million Americans say the internet has played an important or crucial role in helping them deal with at least one major life decision in the past two years.

When the Social Ties Survey showed that people use the internet to activate their social networks when they need help, we followed up in a survey in March 2005 that we call the Major Moments survey. In it we asked Americans if they had faced any of eight different decisions or milestones in their lives in the previous two years. Nearly a third (29%) of American adults said the internet had played a crucial or important role in helping them sort through their options for at least one of the decisions — and some had gone through several of them. Overall, that represents about 60 million adults. The eight major decisions queried in the survey were these:

- Getting additional training for your career: About 21 million said the internet had played a crucial or important role in this.

- Helping another person with a major illness or medical condition*: About 17 million said the internet had played a crucial or important role in this.

- Choosing a school for yourself or a child: About 17 million said the internet had played a crucial or important role in this.

- Buying a car: About 16 million said the internet had played a crucial or important role in this.

- Making a major investment or financial decision*: About 16 million said the internet had played a crucial or important role in this.

- Finding a new place to live*: About 10 million said the internet had played a crucial or important role in this.

- Changing jobs*: About 8 million said the internet had played a crucial or important role in this.

- Dealing oneself with a major illness or health condition*: About 7 million said the internet had played a crucial or important role in this.

(The asterisk marks the five events that were queried in both the Social Ties and Major Moments surveys.)

The number of Americans relying on the internet for major life decisions has increased by one-third since 2002.

When the Pew Internet Project conducted a survey in January 2002 on the same eight life decision points, 45 million adult Americans said then that the internet had played a crucial or important role in at least one of the decisions.

At major moments, some people say the internet helps them connect with other people and experts who help them make choices. Others say that the web helps them get information and compare options as they face decisions.

The internet is important in a variety of ways as people make major decisions, and the most frequently cited benefit was in helping people tap into social networks. Respondents who said the internet was important to them were asked follow-up questions for five of the major life decisions to explore the primary benefit they got from their internet use.1 The five were: buying a car, making a major investment, getting additional career training, choosing a school, and helping someone deal with an illness or health condition.

- 34% of respondents who were asked follow-up questions about five decision topics said the internet helped them find advice and support from other people.

- 28% said the internet helped connect them to expert or professional services, further underscoring the role the internet plays in connecting people to other people in the course of decision-making.

- 30% said the internet provided information that allowed them to compare options. Those who said they bought a car in the past two years were the most likely to say the internet helped them compare options.