Classifying parties as populist

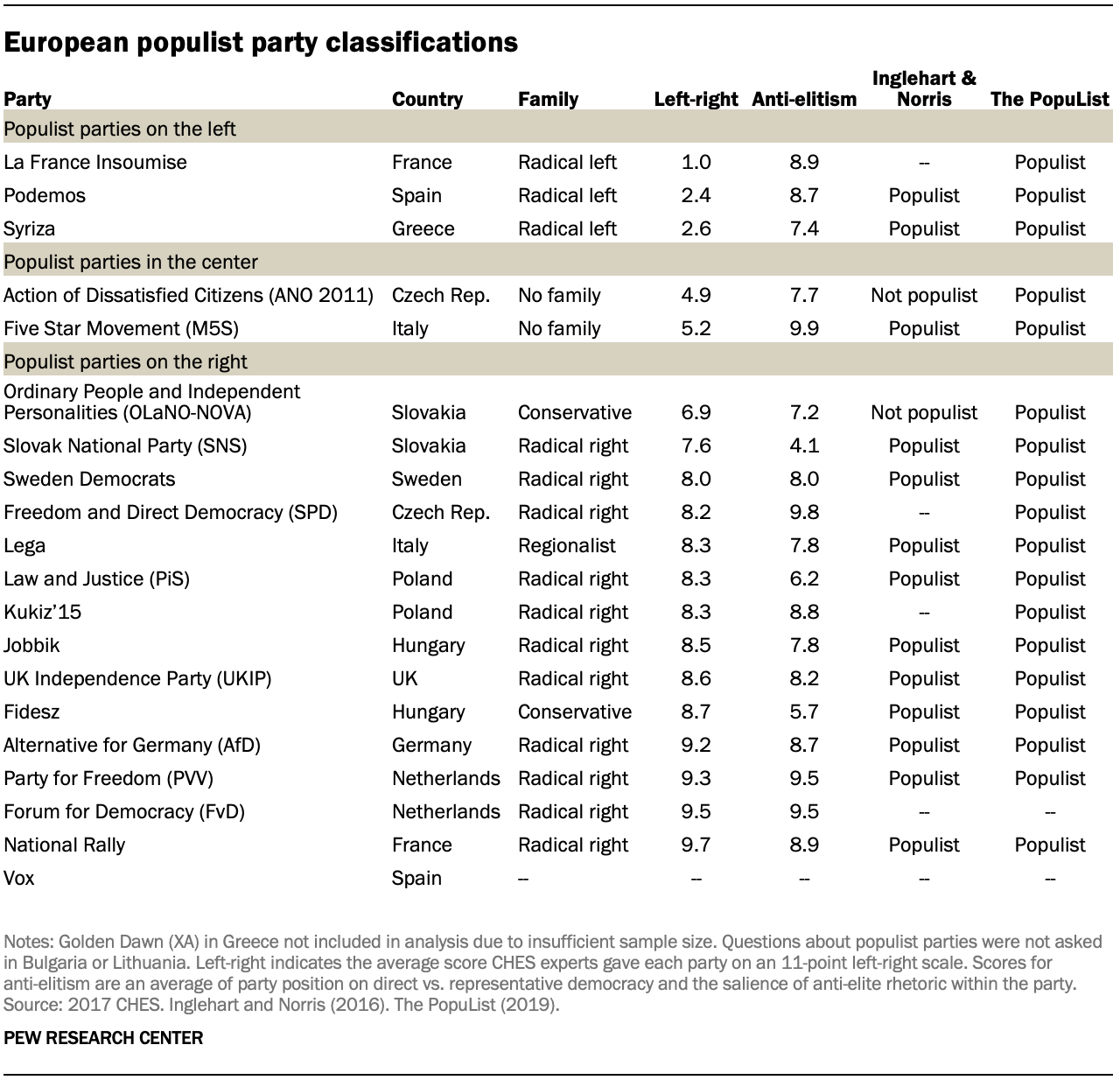

Although experts generally agree that populist political leaders or parties display high levels of anti-elitism, definitions of populism vary. We use three measures to classify populist parties: anti-elite ratings from the 2017 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES), Inglehart and Norris’s populism party scale and The PopuList. We define a party as populist when at least two of these three measures classify it as such.

CHES, which was carried out in January and February 2018, asked 228 regional experts to evaluate the 2017 positions of 132 European political parties across 14 European Union member states. CHES results are regularly used by academics to classify parties with regard to their left-right ideological leanings, their key party platform positions and their degree of populism, among other things.

We measure anti-elitism using an average of two variables in the CHES data. First, we used “PEOPLE_VS_ELITE,” which asked the experts to measure the parties with regard to their position on direct vs. representative democracy, where 0 means that the parties support elected officeholders making the most important decisions and 10 means that “the people,” not politicians, should make the most important decisions. Second, we used “ANTIELITE_SALIENCE,” which is a measure of the salience of anti-establishment and anti-elite rhetoric for that particular party, with 0 meaning not at all salient and 10 meaning extremely salient. The average of these two measures is shown in the table below as “anti-elitism.” In all countries, we consider parties that score above a 7.0 as “populist.”

[European Parliament]

Inglehart and Norris emphasize the cultural views of populist parties and created a populist party scale using the 2014 CHES data for classification.4 This scale aggregates expert ratings of the party on the following positions and attitudes: 1) support for traditional social values, 2) opposition to liberal lifestyles, 3) promotion of nationalism, 4) favorable toward tough law and order, 5) favorable toward assimilation for immigrants and asylum seekers, 6) support for restrictive immigration policies, 7) opposition to more rights for ethnic minorities, 8) support for religious principles in politics and 9) support for rural interests. The scale ranges from 0 to 100, and parties with a score of more than 80 are classified as populist.

The PopuList is an ongoing project to classify European political parties as populist, far right, far left and/or euroskeptic. The project specifically looks at parties that “obtained at least 2% of the vote in at least one national parliamentary election since 1998.” It is based on collaboration between academic experts and journalists. The PopuList classifies parties that emphasize the will of the people against the elite as populist.5

Two parties are missing data for at least two of the measures used for classification but are still included for analysis in the report. Vox in Spain is considered a right-wing populist party by experts, but was not included in any of the measures used due to its relatively recent rise in popularity. Similarly, Forum for Democracy (FvD) in the Netherlands did not achieve a large enough share of the votes to be included in the PopuList analysis and was founded in 2016, after data collection for the Inglehart and Norris analysis. Experts in the most recent round of CHES classify this party as a right-wing populist party, and its score on the anti-elitism scale exceeds the cut-off.

Classifying parties as left, right or center

We can further classify these traditional and populist parties into three groups: left, right and center. When classifying parties based on ideology, we relied on the variable “LRGEN” in the CHES dataset, which asked experts to rate the positions of each party in terms of its overall ideological stance, with 0 meaning extreme left, 5 meaning center and 10 meaning extreme right. We define left parties as those that score below 4.5 and right parties as those above 5.5. Center parties have ratings between 4.5 and 5.5.