In the United States, the practice of leaving gratuities began in the late 1800s and was well established by the Roaring Twenties (read “A brief history of tipping in the United States”). Despite this long history with tipping, Americans express ambivalence or uncertainty on a variety of questions related to it.

Social historians don’t entirely agree about how the custom of tipping originated, but there’s general consensus that it wasn’t common at commercial establishments in the United States, especially outside major cities, until after the Civil War. The practice was spread either by European visitors or by wealthy Americans returning from Europe, where tipping was far more common at the time. (Today, tipping is less common in most of Europe than in North America.)

The practice was reinforced by businesses that employed large numbers of recently freed slaves – most notably, the Pullman railroad sleeping-car company. As tipping critic William R. Scott noted in 1916, nearly all of Pullman’s 6,500 porters were Black men from the South, whose base pay in most cases was $27.50 a month (about $760 in today’s dollars). But the company encouraged passengers to tip, and with tips porters could bring home around $70 to $100 a month or more (roughly $1,900 to $2,800 in today’s dollars).

By the turn of the 20th century, tipping was established enough in the U.S. that some high-end restaurants were actually charging their waiters for the right to work and earn tips. But tipping remained controversial. Some hotel and restaurant managers actively discouraged tips – deeming them essentially bribes for more food or better service, according to business scholar Marc S. Mentzer – and several states tried to ban the practice. Others saw the practice as un-American: Scott wrote that “tipping, and the aristocratic idea it exemplifies, is what we left Europe to escape. It is a cancer in the breast of democracy.”

By the 1920s, financial strains stemming from Prohibition helped solidify tipping’s place in the hospitality industry. Hotels, under pressure to make all aspects of their business self-supporting, switched from the “American Plan,” in which meals are included as part of the room rate, to the “European Plan,” in which meals are paid for separately. Because hotel managers, as Mentzer writes, “were more receptive to their staff receiving tips under [the] European Plan, [their] tendency to respond to Prohibition by switching to the European Plan had the effect of making tipping more common.” They began to view tipping as a way to ease payroll expenses, rather than bribery by customers.

In addition, many hotel bars were turned into “lunch rooms” open to the general public, and a la carte dining grew more common. Tipping became not only tolerated but, before long, widely accepted.

Is tipping more a choice or an obligation?

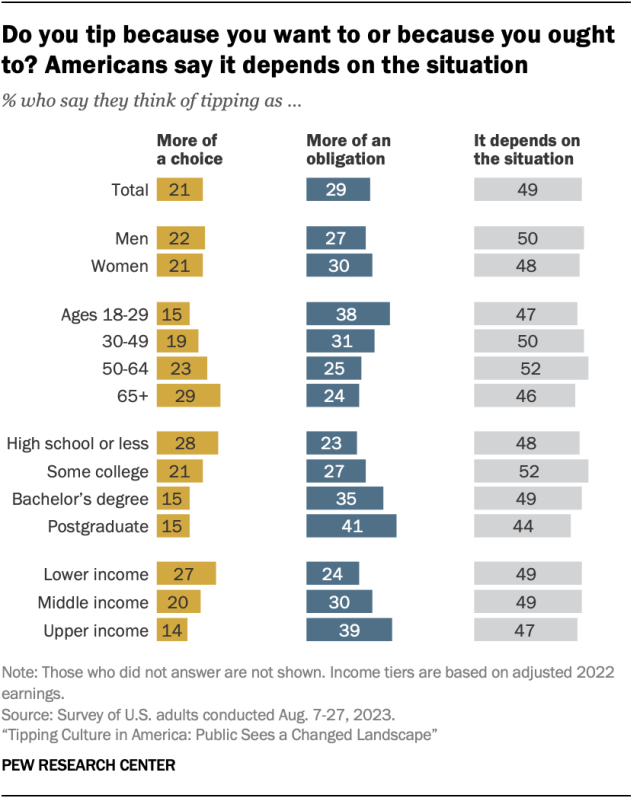

Take the fundamental question of whether tipping is more of a choice or an obligation, or whether it depends on the situation. Overall, 21% of U.S. adults say it’s more of a choice, 29% say it’s more of an obligation and 49% say it depends.

In nearly every demographic group, the largest share of Americans say tipping depends on the situation. But there are still some differences in the public’s views:

Younger people are likelier than older people to see tipping as more of an obligation. Some 38% of adults under 30 say it’s more of an obligation, compared with smaller shares of older Americans.

Conversely, about three-in-ten among those 65 and older (29%) see tipping as more of a choice, while roughly two-in-ten or fewer say this among younger age groups.

The sense of tipping as an obligation rises with income and education. About four-in-ten upper-income adults (39%) say tipping is more of an obligation, compared with 30% of middle-income people and 24% with lower incomes. Similarly, 41% of Americans with postgraduate degrees say it’s more of an obligation; smaller shares of people with lower levels of educational attainment say this.

Related: Do You Tip More or Less Than the Average American?

Uncertainty over whether to tip, and how much

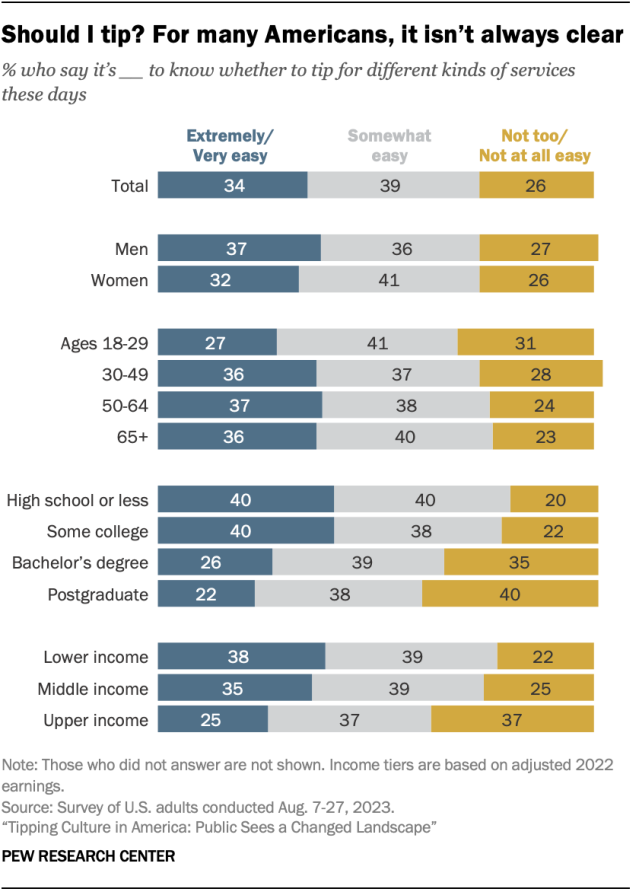

When it comes to knowing whether or how much to tip, relatively few Americans express a great deal of confidence. About a third of U.S. adults (34%) say it’s extremely or very easy to know whether to tip for different kinds of services these days, and a similar share (33%) say the same about knowing how much to tip. Here, too, there are some key demographic differences:

People with upper incomes and those with more education are less confident about tipping than those with lower incomes or less education. For example, only about a quarter of upper-income people (25%) and those with bachelor’s degrees (26%) say it’s extremely or very easy to know whether to tip in a given situation.

Greater shares of those with upper incomes (37%) and bachelor’s degrees (35%) instead say it’s not too or not at all easy. The results were similar when we asked how easy it is to know how much to tip. (For demographic differences on this and other questions in the survey, read the Appendix.)

Men express more confidence than women about tipping. Men are modestly more likely than women to say it’s extremely or very easy to know whether to tip (37% vs. 32%) and how much to tip (37% vs. 29%).

How should tips be distributed?

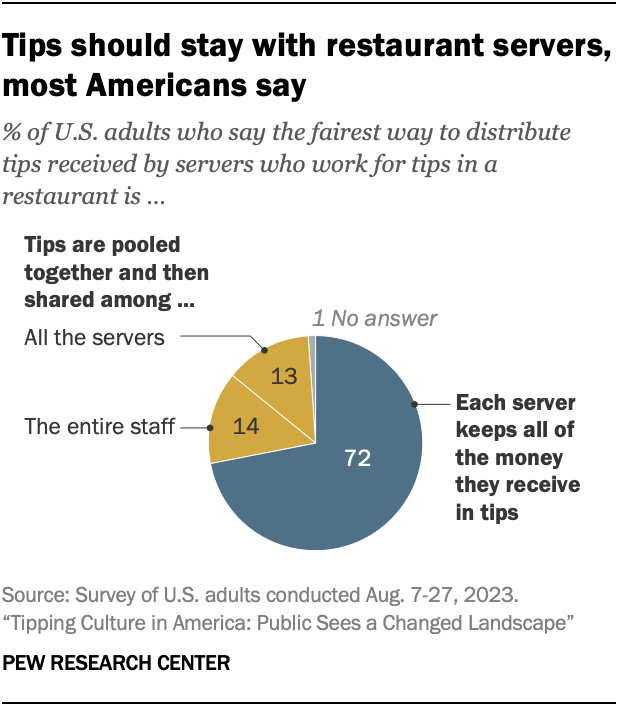

Then there’s the matter of where the tips themselves should go. To assess this, we prompted Americans to think of a restaurant with wait staff who work for tips and asked how those tips should be distributed.

The balance of opinion is clear: A broad majority of Americans (72%) say the fairest way would be for each server to keep all of the money they receive in tips. Far fewer say the fairest way would be for tips to be pooled together and then shared among the entire staff (14%) or among all the servers (13%).

It’s not uncommon for restaurants to require servers (who, by the nature of their jobs, collect the most tips) to share tips with bartenders, food runners, table bussers, hosts and other workers. Such “tip pool” or “tipping out” arrangements are extensively regulated by state and federal law. Certain workers may or may not be eligible to participate, depending on how they’re paid.