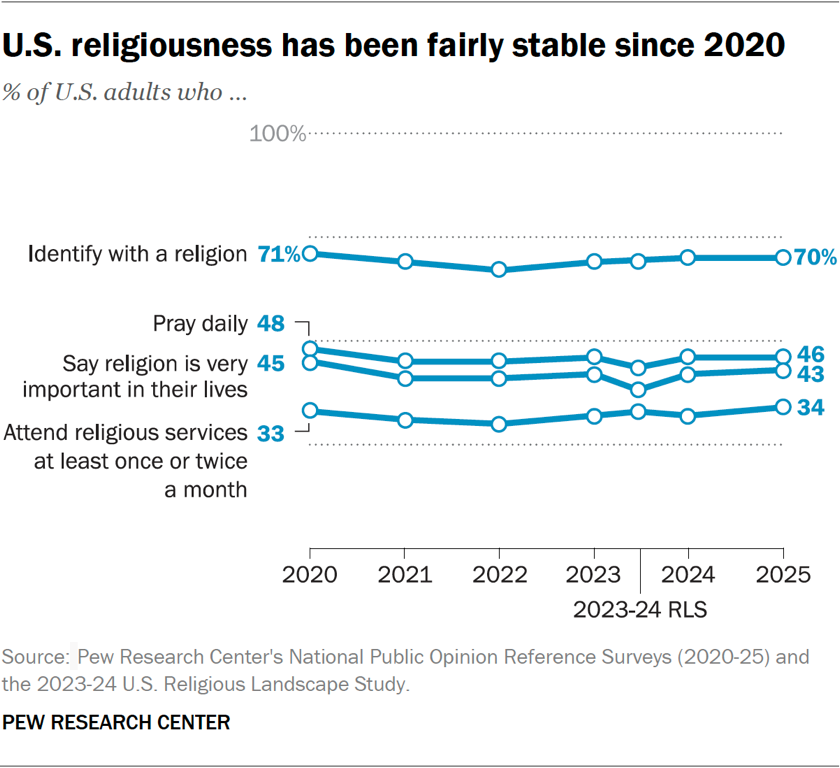

Pew Research Center polling finds that key measures of religiousness are holding steady in the United States, continuing a period of relative stability that began about five years ago.

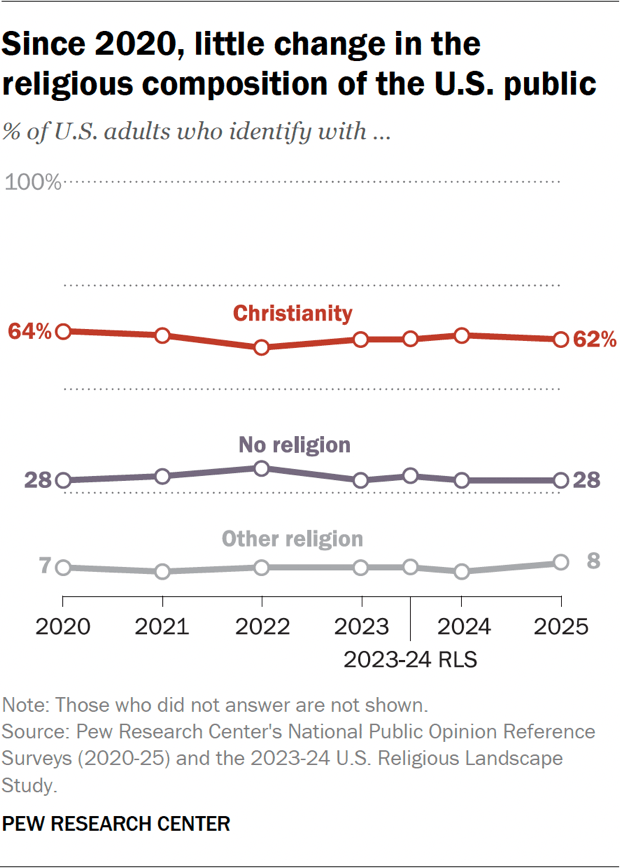

The shares of U.S. adults who identify with Christianity, with another religion, or with no religion have all remained fairly stable in the Center’s latest polling.

The percentages of Americans who say they pray every day, that religion is very important in their lives, and that they regularly attend religious services also have held fairly steady since 2020.

The recent stability is striking because it comes after a prolonged period of religious decline. For decades, measures of religious belonging, behaving and believing had been dropping nationwide.

We know that the previous long-term declines were driven largely by generational shifts. Older “birth cohorts” (i.e, people born during the same time period) tend to be highly religious. As people in these cohorts have died, they’ve been replaced in the population by younger cohorts of adults who are far less religious.

Additionally, people in every birth cohort – from the youngest to the oldest – have grown less religious as they have aged.

So, what is happening with religion among young adults today? Some media reports have suggested there may be a religious revival taking place among young adults, especially young men, in the U.S. But our recent polls, along with other high-quality surveys we have analyzed, show no clear evidence that this kind of nationwide religious resurgence is underway.

On average, young adults remain much less religious than older Americans. Today’s young adults also are less religious than young people were a decade ago. And there is no indication that young men are converting to Christianity in large numbers.

Of course, it’s possible smaller changes are happening in some places that just aren’t widespread enough to show up in national surveys.

And, to be sure, there are some interesting things happening with religion among young people.

For example, young men are now about as religious as women in the same age group. That’s a notable change from the past, when young women tended to be more religious than young men. It also differs from the pattern seen among older people today: Older women are much more religious than older men.

However, this narrowing of the gender gap is driven by declining religiousness among American women. It is not a result of increases in the religiousness of men.

Our recent data also shows that today’s youngest adults (those between the ages of roughly 18 and 22) are at least as religious as their immediate predecessors (slightly older people now mostly in their mid- to late-20s). But this is not the first time surveys have found levels of religiousness among the youngest adults that match or exceed those of slightly older adults. As they have aged, recent cohorts of the youngest adults have tended to grow less religious, opening gaps with slightly older adults that did not exist at first.

In the rest of this report, we use the Center’s National Public Opinion Reference Survey (NPORS), the 2023-24 U.S. Religious Landscape Study (RLS), and other datasets to explore the following questions:

- How is American religion showing signs of recent stability?

- What is happening with religion among young people today?

- How do today’s young adults compare religiously with young adults of the past?

- How do young men compare religiously with young women?

- How many young people are converting to Christianity?

- What do other surveys show about trends in religion?

How is American religion showing signs of recent stability?

In surveys we’ve conducted since 2020, we’ve generally found that about 70% of U.S. adults identify with a religion (such as Christianity, Judaism, Islam or another religion). While the numbers have fluctuated a little, there has been no clear rise or fall in religious affiliation over the last five years.

The surveys show a similar pattern when it comes to how often Americans pray, how important they say religion is in their lives, and how often they attend religious services. There is some bouncing around from year to year, as is to be expected in survey research. But there is no clear trend of either increasing or decreasing religiousness since 2020.

What is happening with religion among young people today?

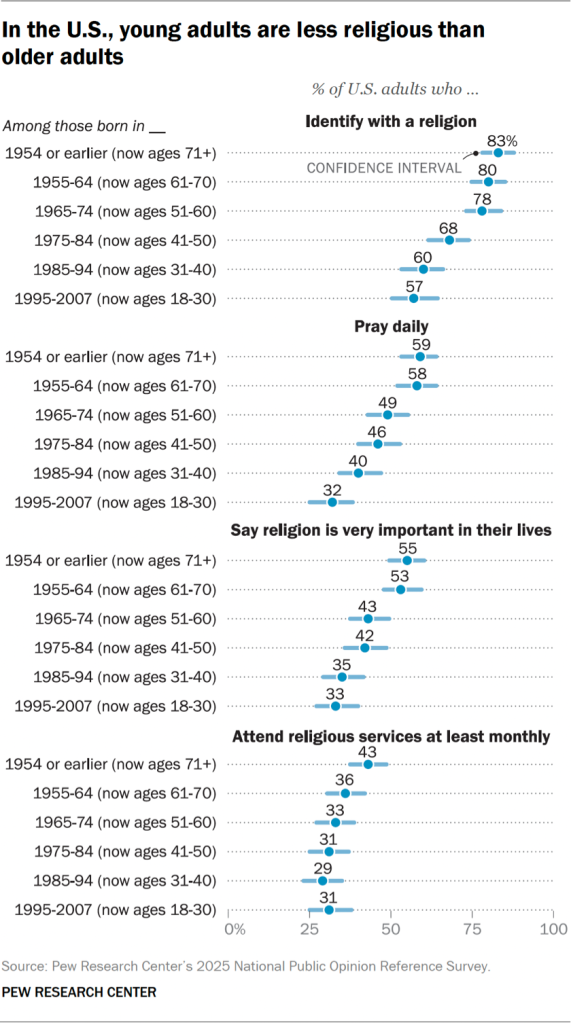

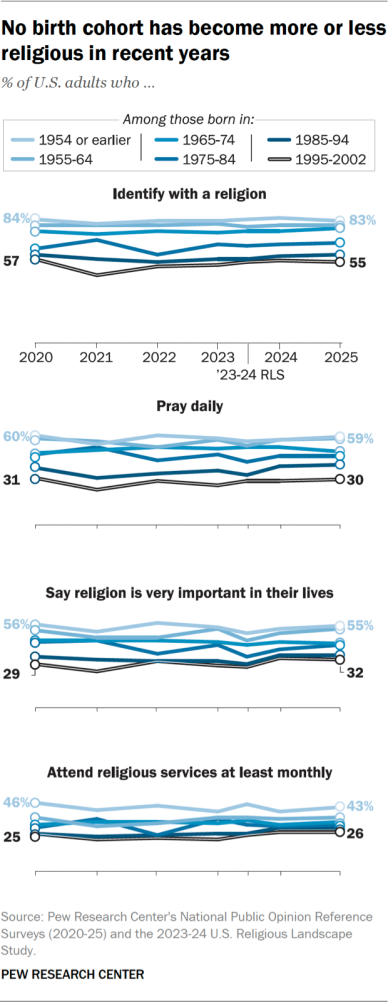

When we look at religiousness among birth cohorts, two patterns jump out.

First, each birth cohort looks pretty stable in recent years. There is no evidence that any birth cohort has become a lot more or less religious since 2020.

For instance, in the 2025 NPORS, 83% of the oldest adults identify with a religion. That’s almost identical to the share measured in the 2020 NPORS (84%).

Similarly, among the youngest adults we track across recent surveys, 55% now identify with a religion. That’s about the same as what we found in 2020 (57%).

(The youngest adults we track over time were born between 1995 and 2002. Today, they are between the ages of 23 and 30. Everyone in this group had already turned 18 at the time of the first survey included in this analysis.)

A second clear pattern in this data is that young adults are much less religious than older people.

In the 2025 NPORS, for example, 59% of the oldest Americans say they pray every day. By contrast, 30% of young adults born between 1995 and 2002 say they pray daily.

And 43% of the oldest Americans say they go to religious services at least once a month. Among people born between 1995 and 2002, 26% say they attend services at least monthly.

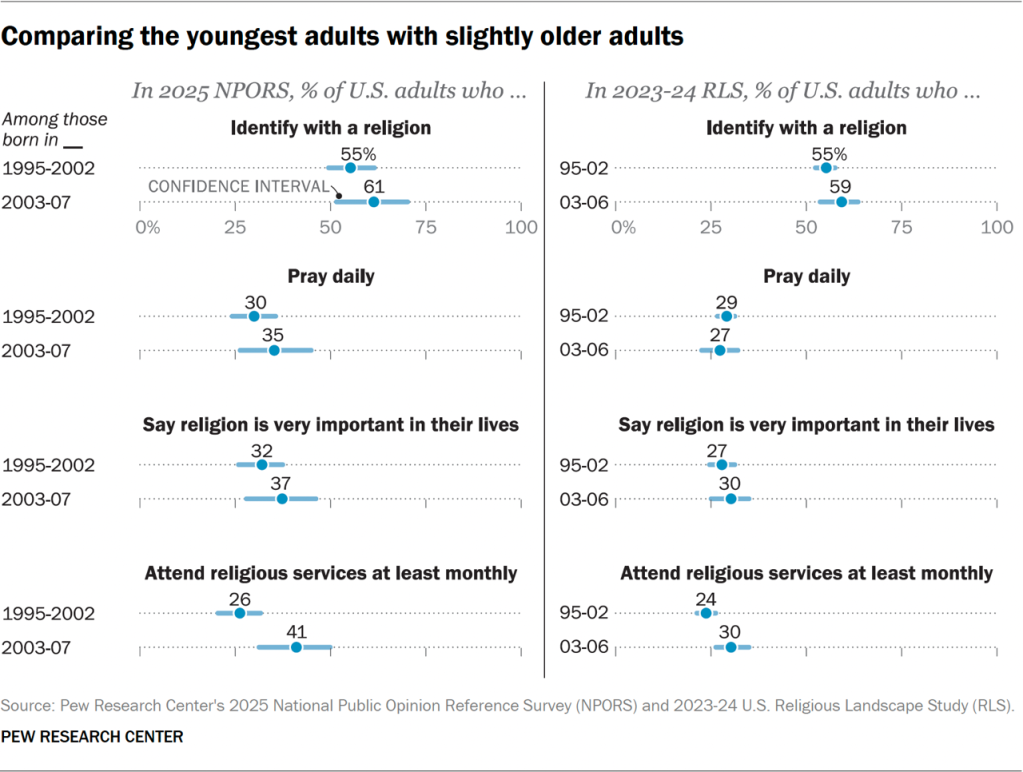

However, today’s youngest adults (people born in 2003 or later) are no less religious than slightly older people born between 1995 and 2002. And in some ways, today’s youngest adults are more religious than today’s second-youngest adults.

In the 2023-24 RLS, for example, 30% of adults born between 2003 and 2006 say they attend religious services at least once a month. That’s somewhat higher than the 24% of people born between 1995 and 2002.

The 2025 NPORS shows a similar pattern, though it should be viewed with caution because the sample of young adults born in 2003 or later is very small (n=154).1

This is not the first time we have seen the youngest adults come of age with levels of religiousness that equal or exceed those of slightly older adults. But analysis shows that a gap between these cohorts tends to appear over time.

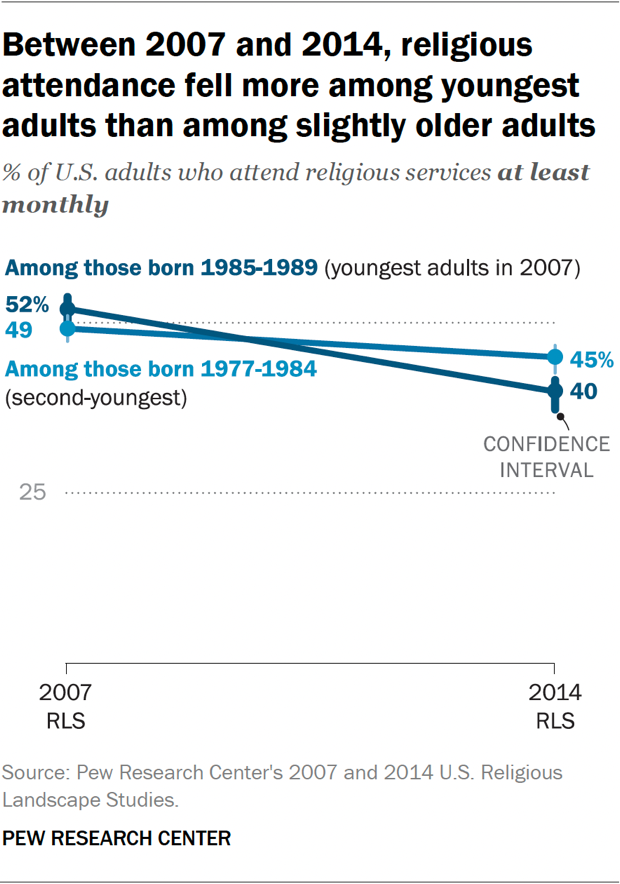

For example, in the 2007 RLS, 52% of the youngest adults reported attending religious services at least monthly. That was very similar to the share among slightly older adults (49%).

Between 2007 and 2014, however, religious attendance dropped among both groups as they aged. And it dropped faster among the youngest group. By 2014, the share saying they attend religious services at least monthly was significantly lower among the youngest adults in 2007 (people born between 1985 and 1989) than among the second-youngest adults in 2007 (people born between 1977 and 1984).2

We see a similar pattern when we compare results from the 2014 RLS and the 2023-24 RLS.3

These patterns may reflect the fact that many of the youngest adults still live in their childhood homes and follow the religious customs of their families.4 As they get older and more of them leave home, their religious habits may change.

Thus, we shouldn’t assume that the religiousness of today’s youngest adults is a sign of a major shift in American religion. Perhaps in the future we’ll look back and see that we were at a pivotal moment in 2025. But historical data suggests the patterns we see today are a normal result of the youngest adults possibly following the religiousness of their parents for a few years past the age of 18, after which their religiousness begins to drop.5

Related: Check out our recent video about religiousness among young Americans, based on data from the 2023-24 RLS.

How do today’s young adults compare religiously with young adults of the past?

The best source the Center has for comparing today’s young adults with young adults from the past are our Religious Landscape Studies. We have done three of these studies – in 2007, 2014 and 2023-24. Each one is based on a massive sample of more than 35,000 U.S. adults. This makes it possible to look at many small groups, including young people. Here, we focus on young adults who were roughly between the ages of 18 to 24 when the surveys were conducted.6

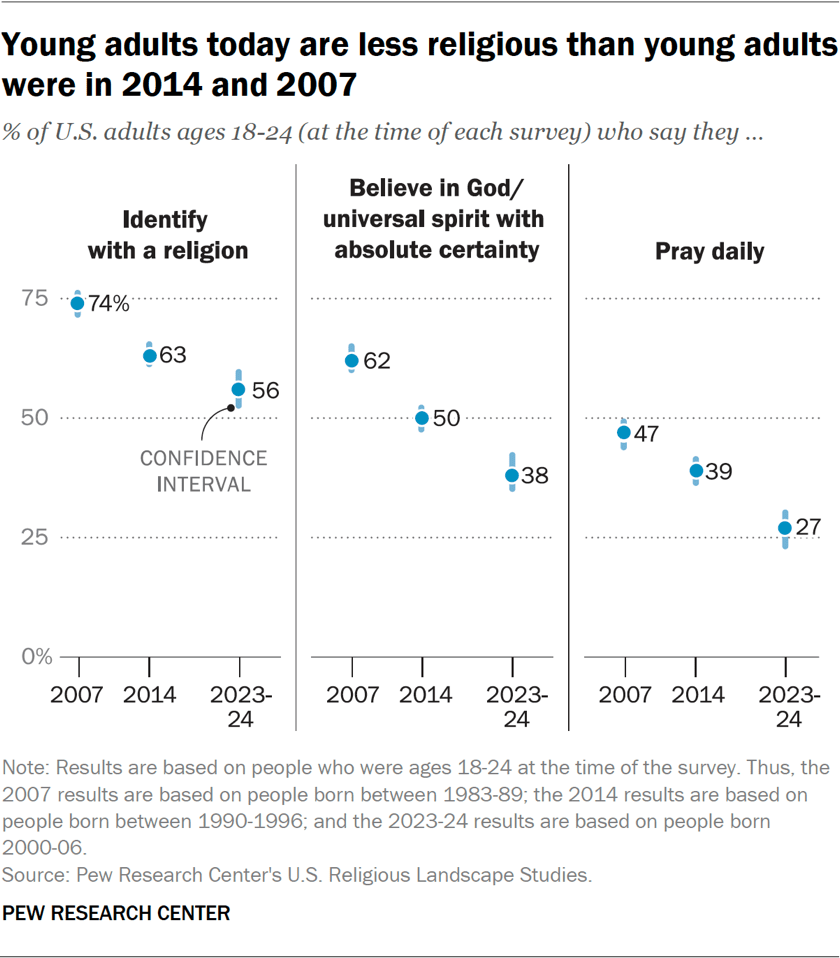

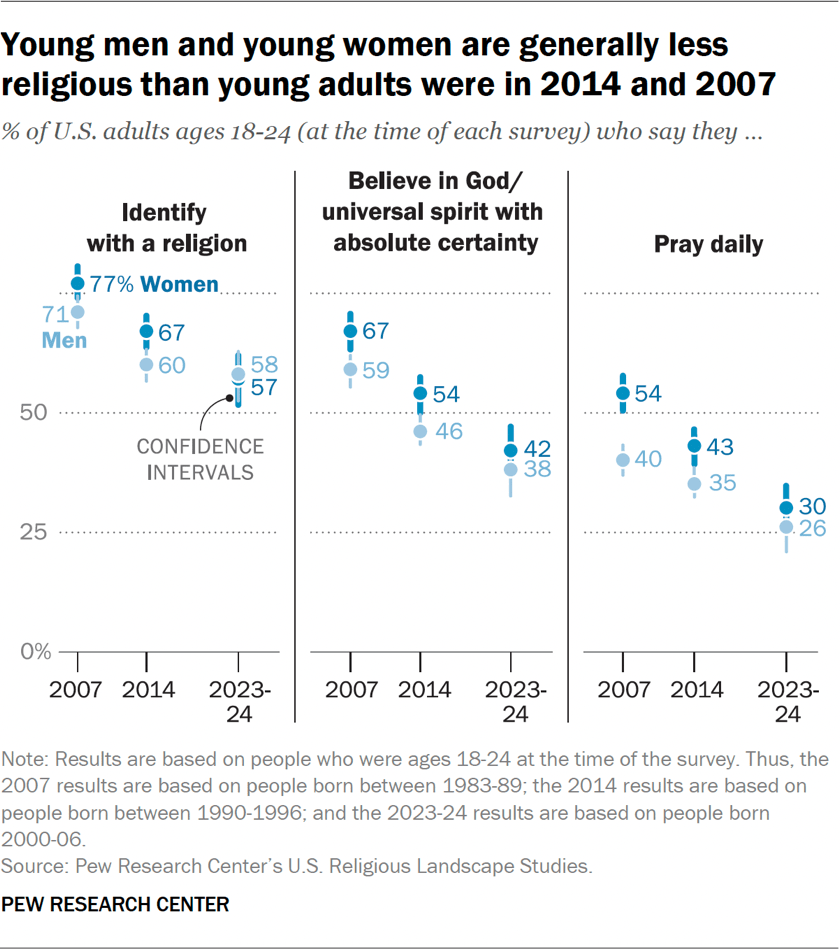

The studies show that young people today are less religious than young people were in both 2007 and 2014.

The best questions we can compare across all three surveys are about religious identity, belief in God and frequency of prayer.7 On all three, people who were ages 18 to 24 in 2023-24 are less religious than people who fell within that age range in 2007 and 2014.

For instance, in the newest RLS, 56% of people ages 18 to 24 identify with a religion. By contrast, in 2014, 63% of people ages 18 to 24 identified with a religion. And in 2007, 74% of people in that age range identified with a religion.

How do young men compare religiously with young women?

In the 2023-24 RLS, there is little difference between the religiousness of young women and young men. For instance, 57% of women ages 18 to 24 identify with a religion. That is virtually identical to the share of men in the same age group who identify with a religion (58%).

And the shares of young women who today say they believe in God or a universal spirit with absolute certainty or that they pray every day are about the same as the shares of young men who say this.8 (The differences between young women and men are not statistically significant.)

This is a notable change. In both the 2007 and 2014 Religious Landscape Studies, young women were significantly more religious than young men on all three of these measures.

The disappearing gender gap among young people has contributed to a narrowing of the gender gap in religiousness among Americans as a whole. Among all U.S. adults, women are still more religious than men, on average. But the gap between women and men is smaller than it once was.

However, it would be a mistake to assume that the narrowing gender gap is a sign that men are becoming more religious. In reality, both men and women – including young men and young women – have become less religious in recent decades. The decline has been particularly steep among women, resulting in a smaller gender gap.

How many young people are converting to Christianity?

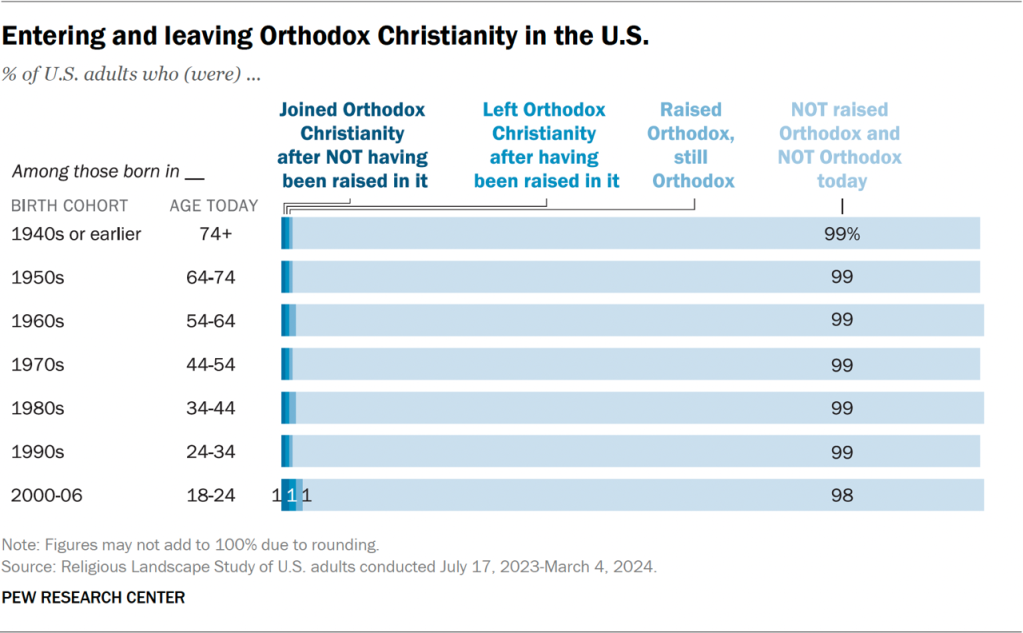

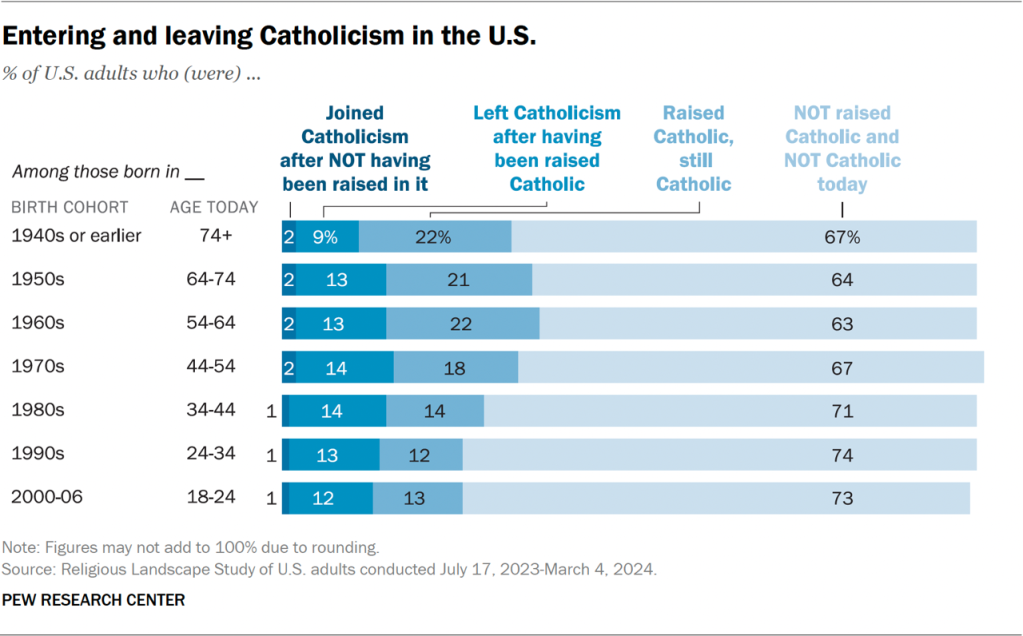

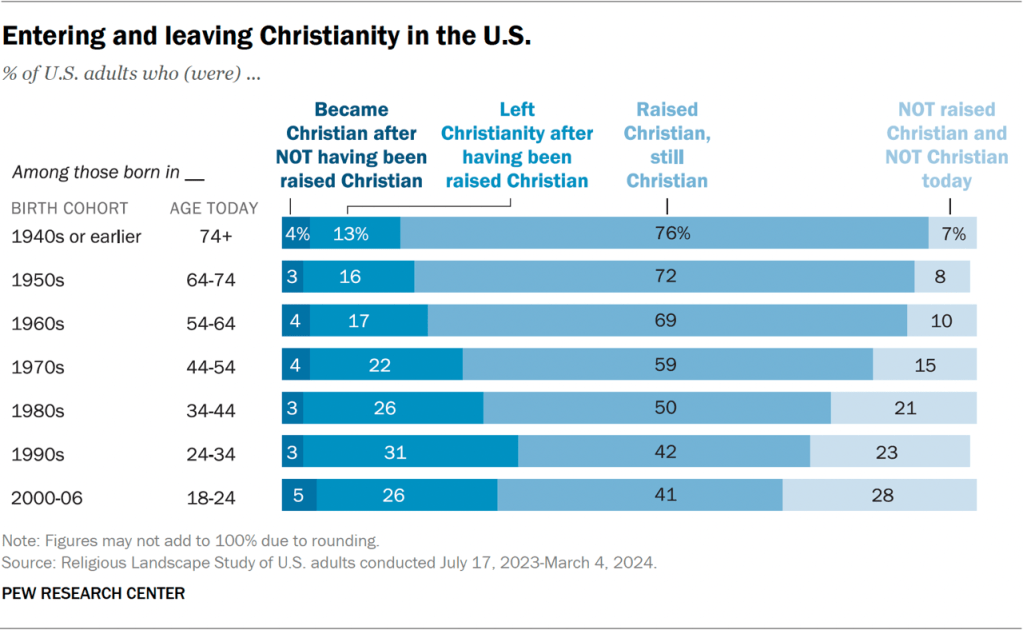

Some recent reports suggest that young people are increasingly turning to traditional forms of Christianity, such as Orthodox Christianity and Catholicism. But the RLS shows that among both younger and older U.S. adults, Christianity loses far more people than it gains through religious switching.

Overall, 1% of U.S. adults ages 18 to 24 now identify as Orthodox Christians after having been raised in another religion or with no religion. An equal share of these adults has left Orthodoxy.

When it comes to Catholicism, far more young people have switched out than in. Overall, 12% of today’s youngest adults have switched out of Catholicism. Meanwhile, 1% of adults ages 18 to 24 have switched into Catholicism, meaning that they identify as Catholic today after having been raised in another religion or no religion.9

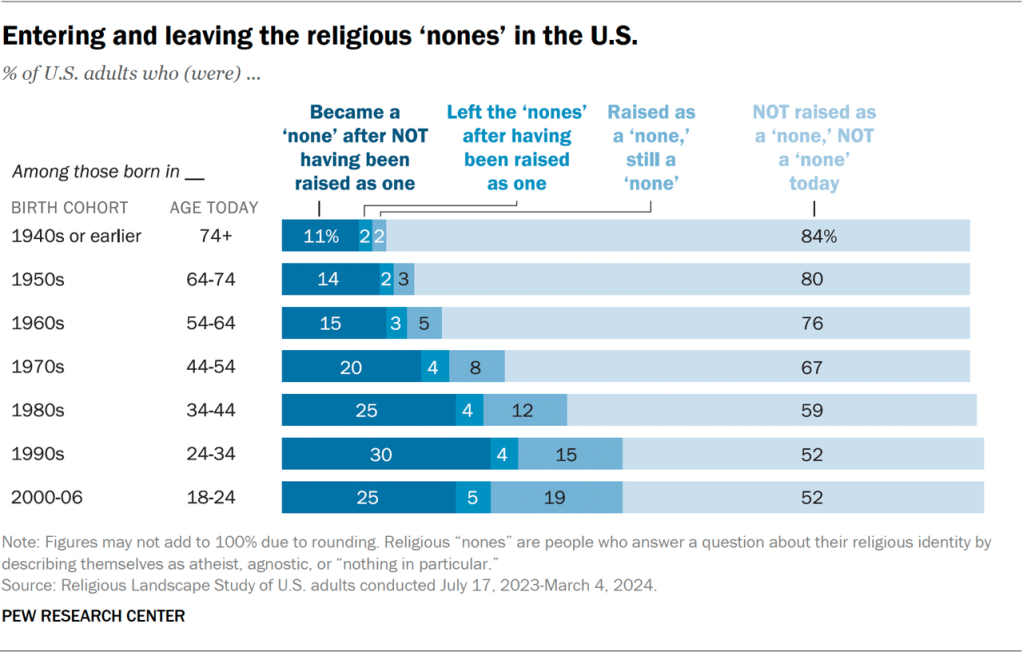

The big-picture outcome of religious switching is a net loss for Christianity and a gain for the religiously unaffiliated. Religiously unaffiliated adults are people who describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” when asked about their religion. We sometimes call this group the religious “nones.”

Among adults ages 18 to 24, 26% are former Christians. By contrast, 5% are converts to Christianity.

This ratio is reversed for religious “nones.” One-quarter of adults ages 18 to 24 have become “nones” after not having been raised as a “none.” Far fewer young adults have left the “nones” after having been raised as a “none” (5%).

What do other surveys show about trends in religion?

We also examined the General Social Survey (GSS) and the American Time Use Survey (ATUS).

The GSS is a national survey of U.S. adults conducted by NORC at the University of Chicago since 1972. Like Pew Research Center surveys, the GSS shows significant long-term declines in the country’s religiousness.

The short-term picture is less clear because of changes in how the GSS is conducted. From 1972 through 2018, it was done mainly through face-to-face interviews. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021 GSS was done mainly online. The 2022 and 2024 waves were done mainly through face-to-face interviewing or online, with a few respondents participating by phone.10

These mode shifts make it difficult to use the GSS to see how religious trends might have shifted between 2018 and 2021.

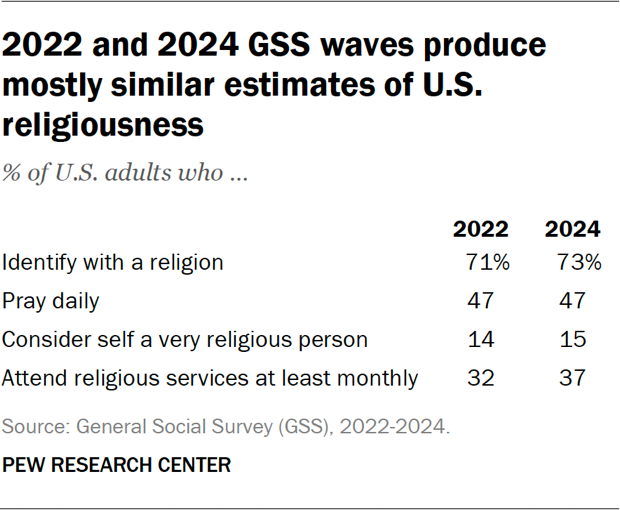

But since the 2022 and 2024 waves were done using similar methods, we can see whether they picked up any signs of religious change.

For the most part, the 2022 and 2024 GSS waves find similar estimates of the country’s religiousness. The shares of people who identify with a religion, pray every day and consider themselves “very religious” are all about the same in the 2024 GSS as in the 2022 GSS. (The differences on these questions are not statistically significant.)

The share of people who say they attend religious services at least once a month is somewhat higher in the 2024 GSS than in the 2022 GSS. Perhaps this is because some people were still staying away from large gatherings in 2022 due to the threat of COVID-19.11

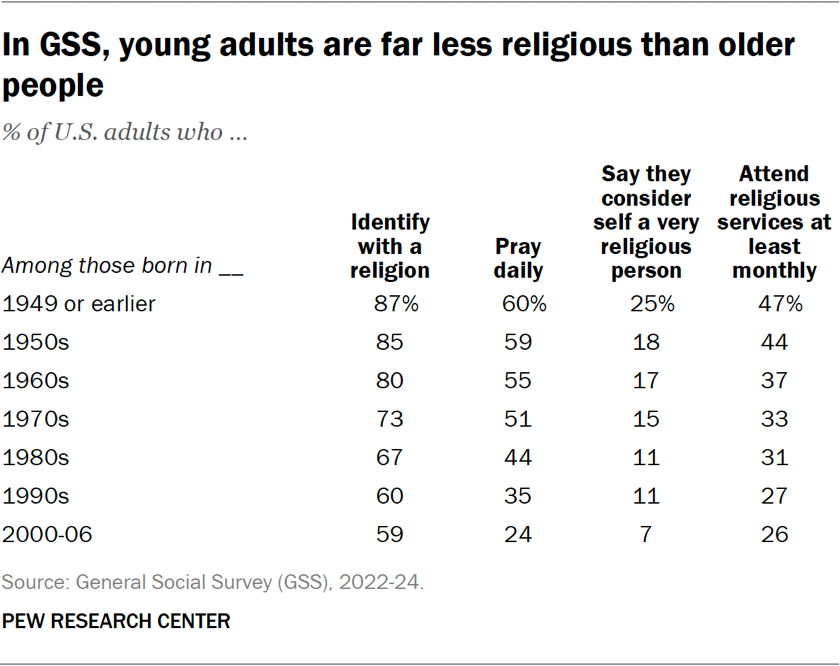

We also combined the 2022 and 2024 GSS waves and looked at how young adults compare with older people.12 (Combining the two waves increases the size of the sample, which is helpful for looking at subgroups.) Like Center surveys, the GSS shows that young people are far less religious than older people.

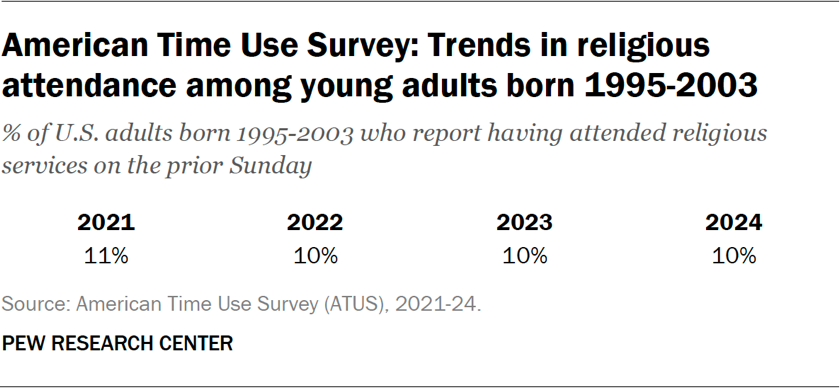

Finally, we looked at data from the ATUS to see if it shows any recent uptick in religious attendance among young adults.13

The ATUS shows no sign that church attendance has increased among young people in recent years. Among adults born between 1995 and 2003, 11% said in 2021 that they’d attended religious services on the prior Sunday. By 2024, that number stood at 10%.14