Partisanship is frequently criticized as a destructive force in U.S. politics, with some arguing it leads to polarization, gridlock, and possibly anti-democratic attitudes and actions. Even the framers of the Constitution warned about its potential for harm. At its base, partisanship is just the simple action of choosing sides – but it’s powerful. Identifying or allying with the Democratic Party or the Republican Party is perhaps the most important predictor of how a person is likely to vote or what opinions they hold about various issues, and that connection has grown over time.

Pollsters and political observers call this “party affiliation” or “party identification.” For at least the past two decades, the vast majority of voters in presidential elections have regularly chosen the candidate of the party they prefer, and partisan differences on political attitudes far surpass those by age, race and ethnicity, and other demographic factors.

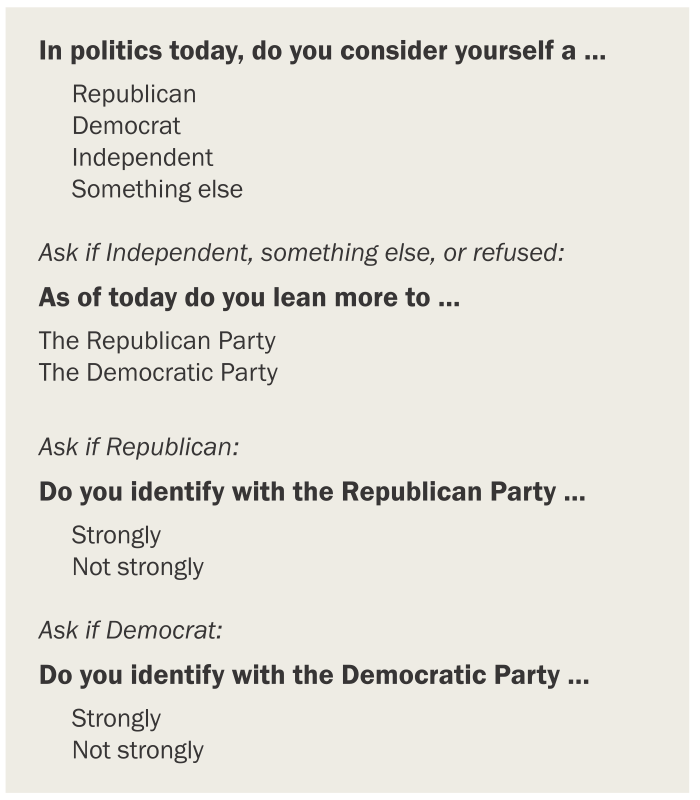

Pollsters typically measure party affiliation in the U.S. by asking people two or three questions. First is whether the respondent considers or thinks of themselves as a Republican, a Democrat, an independent or something else. Anyone who identifies as a Republican or Democrat is classified as such. We typically ask a follow-up question of these individuals to gauge whether they identify “strongly” or “not strongly” with their party. For people who do not identify with either of the two major parties – who describe themselves as independent, as something else or refusing the question altogether – a follow-up question asks whether they “lean” (or feel closer) to one major party or the other.

“Identifying or allying with the Democratic Party or the Republican Party is perhaps the most important predictor of how a person is likely to vote or what opinions they hold about various issues, and that connection has grown over time.”

Most independents aren’t independent

In response to the initial party affiliation question, around four-in-ten Americans decline to say that they “consider themselves” to be a Democrat or a Republican – after all, political parties aren’t very popular these days. But most of those who initially decline to identify with a party will nevertheless indicate a preference between the two parties if asked whether they lean to one party or the other.

Those who pick a party when first asked are, on average, older and more politically engaged than those who don’t pick a party but lean toward one on the second question. However, both those who identify with a party and those who lean toward it are overwhelmingly supportive of that party’s candidates in elections, with leaners only slightly less so. Partisans and leaners also tend to hold similar views on issues. For this reason, Pew Research Center’s standard approach is to report on what is called “leaned party” – analyzing those who identify with and lean toward a party together – when reporting the views of Republicans and Democrats.

But how many real independents, and affiliates of third parties, are there? In our 2023 National Public Opinion Reference Survey (NPORS), 8% of all adults declined to lean to one of the two major parties. The share of the public who does not lean to a party depends to some extent on the mode of the survey and on the wording and format of the question. NPORS is self-administered, either by web or a paper questionnaire. Its version of the political affiliation question does not provide an explicit “no lean” option, which means that people who do not lean must skip the question to indicate this. Some other polling organizations provide an explicit “no lean” option and find somewhat higher shares for the no-lean population. In live interviews, people can volunteer responses that are not explicitly offered, and thus can more easily say that they do not lean, even if not offered an explicit no-lean option.

Though sometimes portrayed as independent-minded swing voters who carefully weigh the issues, the no-lean group is actually much less politically engaged than leaners and partisans. They are less politically interested, less knowledgeable about politics and far less likely to vote.

Declaring a party affiliation when registering to vote

The preference for one party versus another can also be expressed when a person registers to vote. Many states allow voters to identify their party affiliation on their registration, and in some of these states voting in partisan primaries is restricted to people who are registered partisans.

But compared with the standard party affiliation survey question, reported registration with a party (or from the voter’s official state registration record) is not as reliable a predictor of which party’s candidate a person will support. Particularly in states where primaries are not restricted to partisans, a person’s party registration might be quite dated. For example, some older residents of Southern states who now reliably vote Republican remain registered as Democrats, a legacy of when conservative Democrats dominated politics in the region. In addition, many states do not record a party preference when registering a voter. And those that do also permit registration as a member of a minor party, as an independent or as unaffiliated.

Compared with researching these topics in the U.S. electoral system that includes features that make it difficult for third parties to gain a foothold – like single-member legislative districts and the Electoral College – measuring party affiliation in other nations poses different and sometimes steeper polling challenges such as multiparty systems and more formal party registration practices.