One key goal of this research was to identify whether or not online channels of political engagement (social networking sites in particular) may be bringing “new voices” into the political process. Accordingly, our 2012 survey included a series of questions measuring people’s political beliefs and attitudes, in an effort to determine whether different venues for civic behavior may bring a different set of political attitudes into the public sphere. Our goal in doing so was to see if different types of political engagement over-represent (or under-represent) not just particular demographic groups but particular points of view about important issues of note.

In the final analysis, the answer in many ways is “no” — the people who engage politically in online venues have many of the same characteristics, behavioral patterns, and attitudes toward the issues of the day as those who take part in other (offline) types of political activity. Indeed, as we have seen in the preceding analysis, the “online” and “offline” cohorts of politically engaged Americans are in many cases the same set of individuals engaging with political issues across a range of venues or platforms.

In the analysis that follows, we will be comparing four different types of politically active Americans and assessing their attitudes toward various issues. Notably, many people fall into multiple groups because they have performed political activities or communications in online and offline circumstances. In other words, the groups are not mutually exclusive:

- Traditional activists – This group includes anyone who has recently attended a political rally, speech, protest, or local political meeting; worked or volunteered for a political candidate or party; been an active member of a politically oriented group; or worked with fellow citizens to solve a community problem. It represents 48% of the adult population. The college-educated and those with relatively high household incomes are especially likely to fall into this group.

- Offline political communicators – This group includes anyone who has recently contacted a government official in person, by phone, or by letter; signed a paper petition; sent a “letter to the editor” through the regular mail; or called into a live radio or TV show to express an opinion. It represents 39% of the adult population. Whites, the college-educated, and those with relatively high household incomes are especially likely to do this.

- Online political communicators – This group includes anyone who has recently contacted a government official online, by email, or by text message; signed a petition online; sent a “letter to the editor” online, by email, or by text message; or commented on an online news story or blog post to express an opinion about a political or social issue. It represents 34% of the adult population. Demographically, this group looks similar to the offline communicator cohort.

- Political social network users – This group includes anyone who has recently taken part in political activities on social networking sites such as Facebook or Twitter, such as joining a group involved with political or social issues; following political figures; posting thoughts, comments, or links to stories about political/social issues; encouraging friends to take action on an issue or to vote; or liking or promoting material that others have posted. It represents 39% of the adult population. This type of political activity is especially popular with young adults, the college educated, liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans.

Some 28% of Americans fell outside any of these four groups because they had not performed any kind of political activity or engaged in any of the civic-related communications we asked about in our survey. This analysis does not cover these non-political actors.

Attitudes toward social issues

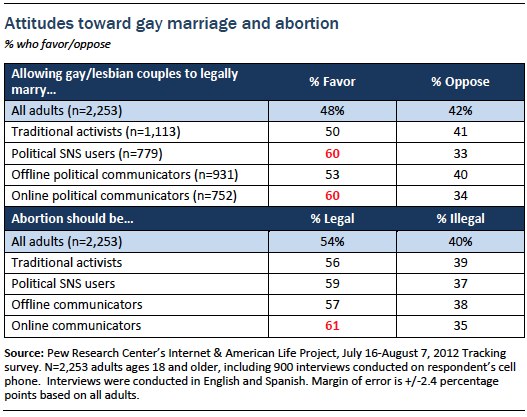

Both the “political SNS user” and “online communicator” groups have somewhat more positive attitudes toward gay marriage than are present in the general population. By a nearly 2-1 margin, each of these groups favor allowing gay and lesbian couples to marry (among all adults, same-sex marriage is favored by a narrower 48%-42% margin). On the other hand, the traditional activist and offline communicator groups largely mirror the general population in their attitudes toward gay marriage. These differences are more muted when it comes to attitudes toward abortion.

Personal economic setbacks

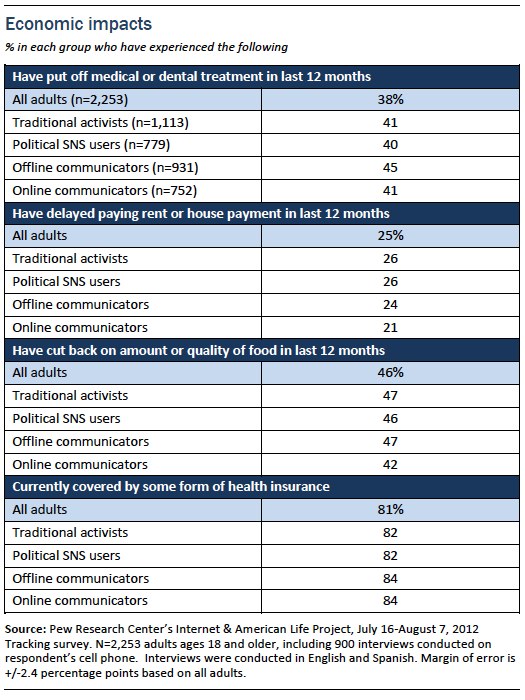

Despite some differences in their demographic composition, each of these four groups has been affected by the recent recession and poor economy in ways that are similar to their fellow Americans in the population at large. Generally speaking, these groups are no more or less likely than average to have recently needed to put off medical or dental treatment, delay a mortgage or rent payment, or cut back on food. Their rates of health insurance coverage are also nearly identical to that of the general population.

Overall, some 56% of the population experienced at least one of three economic impacts we asked about (putting off medical or dental treatment, delaying a rent or house payment, cutting back on amount or quality of food) in the 12 months preceding our survey. And when we directly compare the economically “affected” (i.e. those who have experienced one or more of those impacts) to the rest of the population that has not experienced these impacts, we find that:

- The “affected” are no less likely to own a cell phone, to use the internet, or to use social networking sites. However, they are less likely to own a tablet computer.

- They engage in political discussions at similar rates, both online and offline.

- They are equally likely to directly take part in an in-person political group or activity. Indeed, the “affected” are slightly more likely to have recently attended an organized protest or a local political meeting.

- They are equally likely to receive political outreach messages across a range of platforms.

- They are less likely to make a campaign contribution, although 13% have done so in the last year (compared with 20% of those who have not experienced any of these impacts).

- They are equally likely to publicly speak out about issues that are important to them in online forums, and a bit more likely (by a 41%-36% margin) to do so in offline forums.

- They are equally likely to take part in political actions or discussions on social networking sites, and are in fact a bit more likely (by a 35%-27% margin) to encourage others to take action about issues that are important to them on these spaces.

It may seem counter-intuitive that the “affected” group is so politically active given the great importance of socio-economic factors when it comes to political engagement. But while this group does have lower incomes relative to those who have not been impacted significantly by the recent recession, nearly half (48%) have at least some post-high school education (indeed, one in five has a college or post-graduate degree) and they are also younger than those who have experienced fewer economic impacts. In other words, their age and education levels place them in a relatively “high activity” category, even as their income levels might indicate a lower degree of political engagement. Ultimately, the recession and its aftermath have had a broad impact on the population, but was in many ways especially impactful on younger Americans — even those with relatively high levels of formal education.

Political attitudes

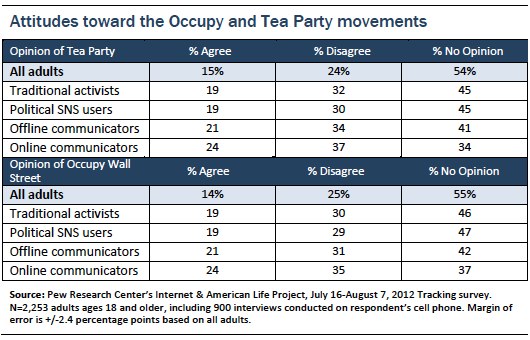

When it comes to their opinions of the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street movements, each of the various politically active cohorts studied here are generally more “opinionated” than the population at large. That is, they contain a higher proportion of people who agree with these movements, and also a higher proportion of people who disagree with them.

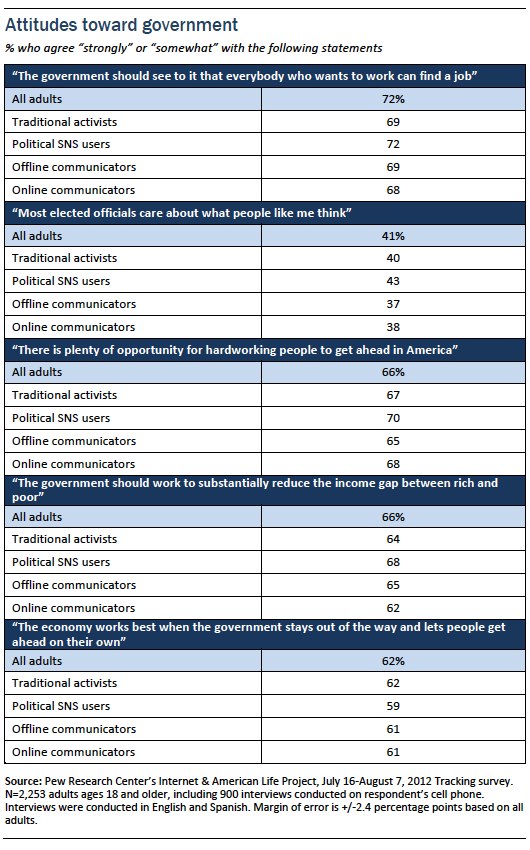

Despite being more likely to have opinions about the Tea Party or Occupy Wall Street movements, all four of the groups have nearly identical attitudes when it comes to their general opinions about the role government should play in promoting economic growth and reducing inequality.