What Government Patrons want.

To compare the different means people use to contact government and the outcomes, survey respondents were asked whether they contacted government in the past year (the year prior to the July 2003 survey), and by what means – telephone, Internet, letter, or in-person visits. For analysis of the subsequent series of questions about the reason for the contact and whether the outcome was successful or satisfactory, respondents were asked to keep in mind their last contact with government that excluded mailing in their tax return (although respondents who said their last contact was filing taxes were included as “yes” responses). This allows respondents to focus on something relatively recent that is other than a task that every taxpayer must do. This approach yields a sample of Americans who had a reason to contact government within the past year not related to sending in their tax return. They are referred to as Government Patrons in this report.

Throughout the report, with the exception of Part 4, the analysis refers to Government Patrons, that is, people’s most recent contact with government, not counting sending in a tax return. In Part 4, some of the analysis is of questions asked either of all Internet users or all respondents to the survey.

Government Patrons are people who contact government for reasons other than mailing in tax returns, although people who had issues related to tax preparation were counted as Government Patrons.

The rationale in focusing on people’s last contact with government is to jog respondent’s memories about an interaction with government that is relatively fresh in their minds. We were probing some basic questions: In the course of carrying out transactions with government, making queries, or finding information, are some means of contact associated with higher rates of success and satisfaction than others? How do users of government services rate them? If e-government tools are meant to improve government, what do we know so far from the experience of current e-gov surfers as compared with other means of contacts?

How often do Americans contact government?

In the year prior to the July 2003 survey, more than half of all Americans, some 54%, said they had contacted the government in a way other than mailing in a tax return. Of Americans who did not contact government in the past year, most (60%) did not know that the government has set up Web sites and 800 telephone numbers to assist the general public with questions about government.

Most Americans contacted the government for personal reasons – 71% of Government Patrons said a personal reason motivated their contact with government, while 20% said it was business and 7% said it was a combination of personal and business. Of Government Patrons, fully 79% said the reason they contacted government was not related to filing taxes, with 21% saying it was tax-related. In all, 30% of Americans get hold of government for personal reasons not related to taxes, 9% do so for personal tax reasons, 12% for a business reason that is not related to taxes, and 3% for a tax reason related to their business.

Americans spread their government contact around: 35% say they last contacted the state government, 32% identify the federal government, 19% say local, and 7% a combination of governmental levels. Some people (21%) first turn to some place outside of government for a problem for which they eventually turn to government.

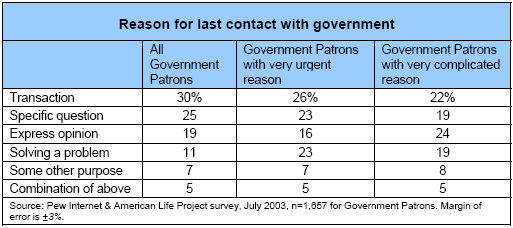

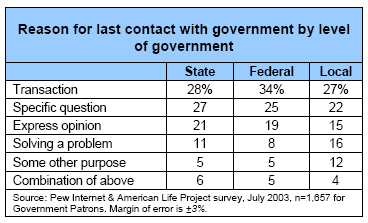

Why did Government Patrons contact government agencies? The most common reason, cited by 30% of Government Patrons, was to carry out a transaction of some sort, such as filing taxes or registering the car. Another 25% said they had contacted government to get an answer to a specific question. Nearly one-fifth (19%) said they had contacted the government to express an opinion, and 11% sought out help for a specific problem. A few (5%) offered that they had contacted government for a combination of reasons mentioned above, with the balance giving some other or no response.

In characterizing the nature of the contact, 31% said it was complicated (9% saying it was very complicated, 22% saying “somewhat” complicated), with the remaining two-thirds (68%) saying it was not really complicated at all. Respondents were also asked how urgent their contact was, and 11% said it was very urgent, meaning they needed a response within 24 hours. Another 39% said it was somewhat urgent, and 48% said it was not really urgent at all.

Contacts that are very urgent are driven partly by problems that need to be solved; 23% of people whose issues with government are very urgent say they contacted government because they needed help solving a problem. This is twice the rate for all Government Patrons. People contacting government for very complicated reasons are less likely than others to want to perform transactions (22% versus 30% for all Government Patrons). Those contacting the government with complicated issues in mind are more likely to be expressing opinions (24% versus 19% for all Government Patrons) and seeking help for a specific problem (19% versus 11% for all Government Patrons).

The means people use to contact government

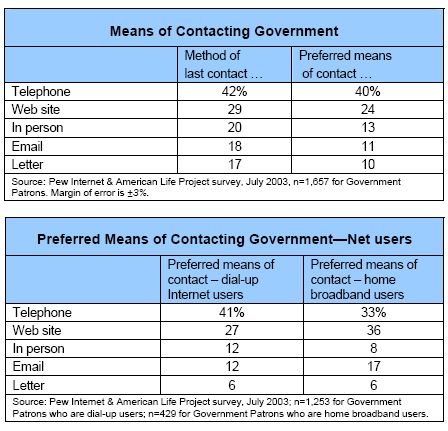

The telephone leads the way in terms of method of last contact and preferred means of contact. For method of last contact, however, cyber means – either email or visiting a Web site – exceed the frequency of telephonic means when summed together. That is not the case for preferred means of contact, where telephone is clearly preferred to both Internet methods of contact. The gap between the means people use to contact government and how people prefer to contact government suggests that the Internet may not fulfill all of the needs of Internet users.

Among Internet users, the telephone is the preferred means of contact, but the magnitude of preference depends on the type of connection people have. Dial-up Internet users are most likely to prefer turning to the telephone to contact government. For those with high-speed Internet connections at home (32% of home Internet users in this survey), the Web is narrowly preferred to the telephone as a way to contact government.

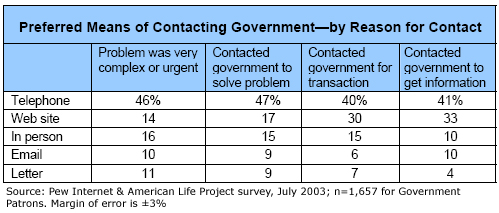

People’s preferred means of contact also varies significantly by the nature of the problem at hand. For the 18% of Government Patrons who classify the reason they contact government as either very complicated or very urgent, “real time” interaction is by far the preferred choice. The telephone or in-person visits are the most valued forms of contact for these kinds of problems, while the Web and email fade in relative importance. The same is true for people who said that they sought out government help to solve a problem the last time they contacted government. For seeking information or executing a transaction, the Web and email become more prominent.

Of course, people are not limited to a single means of contact with government. For Government Patrons, fully 22% said they used a combination of means to contact government. Among those who used multiple means, 71% named the phone as one way they contacted government, with sizable numbers also saying they used the Web or email to contact government (49% and 40% respectively). People often switch means in the course of trying to address an issue with government. Nearly one quarter (23%) of Government Patrons say they change channels during a contact with government, say from phone contact to Web contact. Of these channel changers, 40% say it is because they were not getting the response they needed and 23% say someone instructed them to use a different source.

A profile of those who contact the government

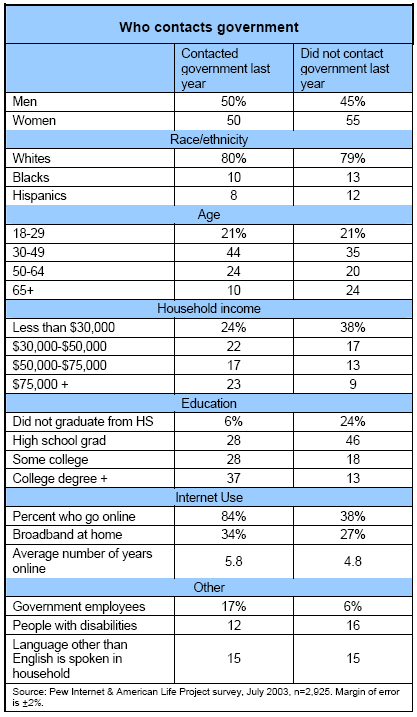

Demographically, those who contact the government are better educated, wealthier, younger, and more likely to be male than the general population. People employed by government (about 19% of those who are employed) are more likely than others to contact the government. As for attitudinal factors, people who are satisfied with the direction of the country are less likely to have contacted government, those who believe that government is wasteful are more likely to contact government, while those who tend to trust government are no more likely than others to contact government.

Although the table shows that people with disabilities are somewhat less likely to contact government, this finding does not hold up when other factors are held constant. Among the factors that do not come significantly into play in people’s tendencies to contact government are race, political affiliation, marital status, or being a parent.3

Internet use seems clearly to come into play when it comes whether people contact government. Fully 72% of Internet users say they contacted the government in the past year versus 23% of non-Internet users. Some might wonder, though, if the large gap is attributable to the Internet or to another phenomenon. For instance, online Americans have other characteristics, such as higher educational levels or incomes, which may be the drivers for higher contact rates with government. Those factors do have an independent effect on whether one contacts government. However, statistical analysis shows that being an Internet user has a large and independent impact on whether one contacts government. In fact, having Internet access is the single largest predictor of whether a person contacts government. This makes sense: The Internet is a means of communication, and given the tool, people put it to use.

Some portion of the additional contact by Internet users may be due to their sending emails to communicate views on public policy issues. Of Internet users who have contacted government, one in eight (13%) does this at least several times a month. Lots of these frequent contactors are using the Net to try to change government policy or affect a politician’s vote on a law; about half of these users (48%) say they email government officials to express a policy opinion versus 27% for other Internet users.

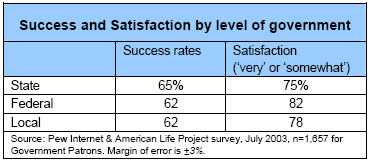

Success and Satisfaction with Government Contact

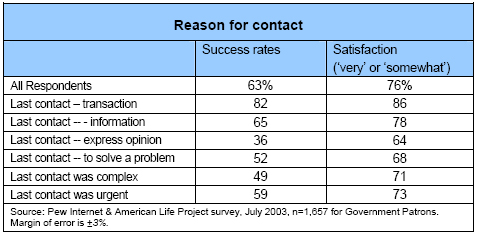

Americans who have contacted government report reasonably high rates of success and satisfaction with the experience. Fully 63% of targeted contacts (Americans who contacted government in the past year) said that the outcome was successful, with 25% saying they were still working on the problem, and 10% saying the outcome was not successful. As for satisfaction, 76% of Government Patrons say they were “very” or “somewhat” satisfied with their last contact with government, with 35% saying they were very satisfied and 41% reporting that they were somewhat satisfied. Nearly half (46%) said the contact took about the amount of time they expected, while 28% said it took longer than they anticipated.

Most people are successful when trying to conduct a transaction with government, probably because transactions have a visible finish line that enables citizens to identify success or failure. More challenging kinds of citizen-government contact have lower rates of success. Just over half of those who contacted government in the past year in order to solve a problem said they were successful, and half who contacted the government regarding a complex matter were successful. Comparatively few people who contact the government to express an opinion consider the outcome of this contact successful. Given the difficulty in tracing how expressing one’s opinion translates into changing or even influencing an outcome, this is not surprising.

Demographic variations in success and satisfaction

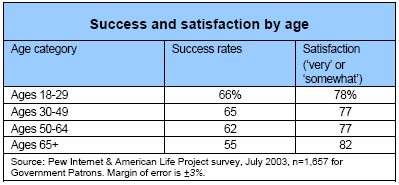

Looking at demographics, some clear patterns emerge. People over age 65 report lower levels of success than others, although intriguingly they express higher rates of satisfaction with government. This may be due to the different motivations senior citizens have when they contact government. Those over age 65 are much more likely to contact government to express an opinion (33% versus the 19% average) and this reason for contact is associated with much lower reported rates of success, but only somewhat lower-than-average rates of satisfaction.

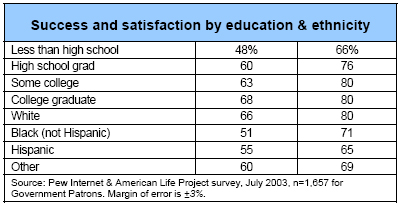

Other demographic factors mark clear dividing lines for success and satisfaction with government contacts. The 20 percentage-point difference in success between those who have not completed high school and those who are college graduates suggests that the human capital that people bring to interactions with government has something to do with success. Differences by ethnicity are less marked, although there are clear gaps between whites, blacks, and Hispanics when it comes to success and satisfaction with interactions with government.

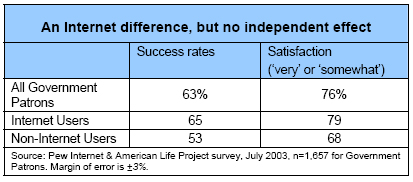

An Internet difference, but no independent effect

Internet use also seems to be associated with higher rates of success with government; 65% of Net users report success while just over half (53%) of non-users say this. (The 65% success rate among Internet users is the same for home broadband and dial-up users.) As the preceding discussion suggests, however, a lot is in motion when people contact government. Rates of success and satisfaction vary widely by demographic characteristics and reason for contact. It may not be the case that the Internet is a reason for the higher success rates among users; Net users may possess particular qualities that contribute to success that have nothing to do with whether they use the Internet or not. To disentangle the different effects, regression analysis was performed to examine what demographic, socioeconomic, and other factors might be associated with success and satisfaction in contacting government.

The analysis shows that being an Internet user does not have an independent impact on the chances of a person being successful in interactions with government. The same is true for satisfaction; being an Internet user does not increase the chances that someone rates their last contact with government as something that was “very” or “somewhat” satisfactory. In other words, though Internet users are more likely in our survey to say they have been successful or satisfied with their last government contact, Internet use in itself is not responsible for these differences.

When it comes to success with the last government contact, a number of factors do figure in the chances of success or failure. People who say that they generally trust the government to do the right thing, are satisfied with the direction of the country, and are well educated have greater chances to be successful in their dealings with government than those without those characteristics. Conversely, people who say they think government is generally wasteful are less likely than others to say that their last interaction with government was successful.

The story is much the same when examining satisfaction with a respondents’ last government contact. Positive attitudes about government, such as trust in its ability to do the right thing and high levels of satisfaction about the direction of the country, are independently associated with satisfaction with respondents’ last contact with government. Educational attainment is also an independent predictor of satisfaction, though the magnitude of this effect is lower than when the analysis focuses on success.

One notable finding from the regression analysis is that people whose last means of contact was the Web or the telephone are more likely to be successful with government, even when holding type of transaction and other social and demographic factors constant. The Web applications they encounter may not necessarily be behind this effect, but rather the skill people bring to the task at hand.4 Those who prefer interactive means of communication, such as the phone or the Internet, bring more education and, in all likelihood, better problem-solving skills to the matter at hand. The Internet and the telephone are convenient means to address the issues people have with government, but offer no inherent capacities to solve problems better.

The Internet saves some time

Although having the Internet does not, independently, improve outcomes for people, it does seem to save some time. About 46% of Government Patrons said their last interaction with government took about the amount of time they expected, 28% said it took more time than expected, and 24% said less time. Focusing on Internet users versus non-users shows that Internet users moved through their last contact with government a bit quicker than those without Net access. Fully 35% of non-users said their last contact with government took more time than expected, a nine-point difference in comparison with the 26% of Internet users who said it took more time than expected. About 27% of Internet said the interaction with government took less time than expected compared with 22% of non-users. Among Internet users, there was no difference between dial-up and home broadband users in these numbers.

Internet users are more likely than non-users to say that their last contact with government took less time than expected.

In keeping with the notion that people’s problem-solving abilities are important in their dealings with government, higher levels of education are associated with moving through government interactions somewhat faster or in about the expected time. Fully 56% of people with college degrees or higher say their last contact with government took approximately the amount of time they expected, 24% said it took more time than expected, and 18% said less time.5

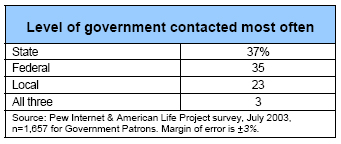

Contacting different levels of government

We asked Government Patrons which level of government they contact most often and found that there are differences in how people contact government across the different levels, the reasons for contact and, to a lesser extent, in rates of success and satisfaction. As the table shows below, more than two-thirds of government patrons contact state or federal governments, with local governments less likely to be contacted.

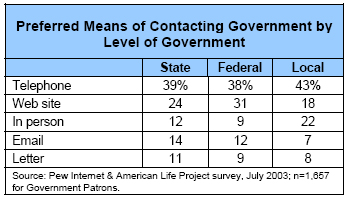

As for preferred means of contact, Government Patrons favor phone calls or in-person visits as a means of contact for local government, while clicking on a Web site is a relatively strong preference for those who contact the Federal government.

There are also differences in why people contact governments at different levels as well as minor ones when it comes to success and satisfaction.

Proximity probably explains some of the difference in preferred means of contact between those contacting local governments and other levels of government. The ease of the no-cost local phone call or the drive down to city hall is likely behind why phone calling or in-person visits are preferred by nearly two-thirds of those who contact local government most often. The distance between state capitals and the nation’s capital for most people may make clicking on a Web site relatively more attractive than a toll call or a trip to an agency’s office.

Tax reasons may be a reason for the emphasis on transactions among Government Patrons who contact the federal government most often. Because transactions, as discussed above, are associated with higher rates of satisfaction among government patrons, this may be a reason why satisfaction levels are higher among those who contact the federal government.

The Tax Man

Of Americans who have contacted government in the past year, about 20% do so for reasons having to do with their taxes – a query that is different from simply mailing in their tax returns. For people with tax concerns, the phone and the Web were the main means of contact. Fully 51% of those with tax queries picked up the telephone to approach the government and 40% used the Web; this compares with 40% of Government Patrons with non-tax related questions who used the telephone and 26% who used the Web. Both groups were equally likely to use a combination of methods (22%). Most of the tax queries were for personal reasons (77%), with the remaining 23% being either for business purposes or a combination of personal and business; this compares with 69% and 28% respectively for non-tax queries.

One in five Government Patrons got hold of government to ask a question about taxes.

Most of those who contact government to inquire about their taxes consider this contact a transaction – 66% do, with another 16% saying the reason is to get an answer about a specific question. About one-quarter (27%) of those with tax concerns switched means of contact during their contact with government and half (49%) did so because they were not getting the response they needed. This compares with 22% who switched when contacting government for non-tax reasons; 38% of these people switched because they were not getting the answer they needed. Finally – and likely because of the transactional nature of the inquiry – fully 76% of those who had a tax question of government said their interaction was successful. Of Government Patrons who did not have a tax question, 60% said their interaction with government was successful.

Those with disabilities

People with disabilities make up an important sub-population of Americans. About one in seven (14%) of respondents said they have a disability of some sort, and they tend to be the elderly. Fully one-third (34%) of those with disabilities are over age 65 versus 11% of the rest of the population. People with disabilities exhibit other differences compared with the rest of the population. Fewer are Internet users – 40% of those with disabilities use the Internet. In addition, more are female (55%), and, as a group, they are less educated. Some13% have college degrees, about half the rate of the general population). Among those who are Internet users, 16% say their disability makes it harder to use the Internet. Among non-Internet users, 22% say that their disability would make it difficult or impossible to use the Internet.

People with disabilities are more likely to contact government with complex and urgent problems, and they prefer the telephone or in-person visits as the way to address these problems.

People with disabilities also differ when it comes to government contact. A bit less than half (48%) have contacted the government in the past year, and they are less likely than others to say their interactions with government have been successful (52% say this versus the 63% average).6 Seventy percent say they were satisfied with their last contact with government compared with the average of 76%.

One reason for their comparatively low rates of success and satisfaction relates to the reasons that those with disabilities have for contacting government. One in six (16%) say their query of government was “very” complicated and 21% said it was “very urgent”; both numbers are about twice the rate for all Government Patrons. People with disabilities also are more likely to say the reason they contact government is to get information to answer a specific question; 22% say this, which is twice the rate for all Government Patrons. Finally, due to the low Internet penetration rate among this segment of the population, cyber means of contacting the government is not preferred by people with disabilities. Among Government Patrons with disabilities, 44% say they prefer the telephone to contact government, 21% prefer visiting in person, and 16% prefer to write a letter. Just 9% say they prefer visiting a Web site and 6% prefer email.