The failure of Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi’s constitutional reform referendum has rattled the already shaky nerves of European political elites. On the heels of Brexit and Donald Trump’s victory, the Italian verdict highlights once more the depth of public anger with the political establishment in Western nations. And with elections approaching in the Netherlands, France and Germany, many worry that 2017 could be at least as politically disruptive as 2016 has been.

Pew Research Center surveys have highlighted a variety of factors driving the anti-establishment sentiments spreading throughout much of Europe, including economic anxieties, security fears, cultural unease and a lack of confidence in political institutions.

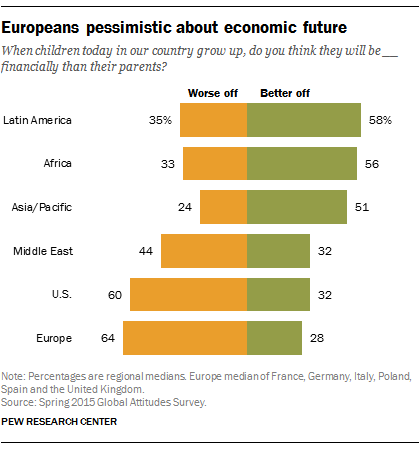

Europeans are pessimistic about their long-term economic future. Many are unhappy with the current state of the economy in Europe: In five of the 10 European nations we polled earlier this year, majorities described the economic situation in the country as bad. But perhaps more troublingly, Europeans have a grim view about the economic prospects for the next generation. In 2015, we asked people in 40 nations around the world whether children in their country will be better or worse off financially than their parents when they grow up. In Latin America, Africa and Asia, people tended to believe the next generation would be better off, but in the Middle East, the United States and especially in Europe, there was widespread pessimism.

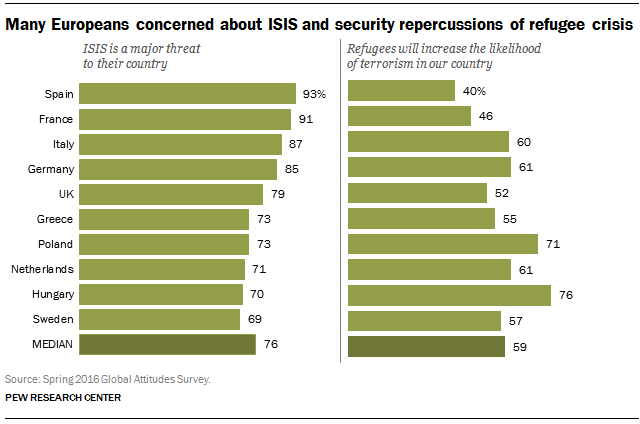

Concerns about terrorism are pervasive in Europe, and many see a link between the refugee issue and terrorism. When asked about a variety of international threats, publics in nine of 10 European countries surveyed named ISIS as their top concern, illustrating the strong worries Europeans have about terrorism in the wake of attacks in Paris, Brussels and elsewhere. (The exception was Greece, where respondents cited global economic instability and global climate change ahead of ISIS.) And importantly, many see a connection between terrorism and the wave of refugees into Europe from the Middle East and other regions over the past two years. Across 10 European nations, a median of 59% said the influx of refugees would increase the likelihood of terrorism in their country.

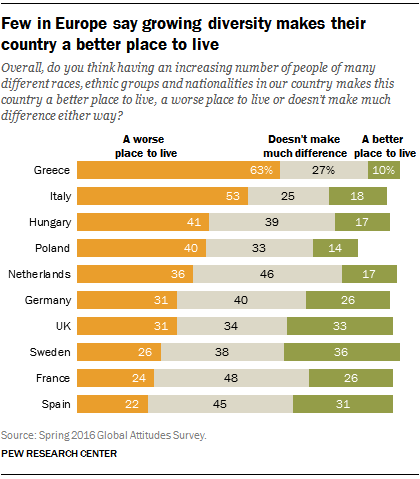

Many Europeans are uncomfortable with the growing diversity of society. When asked whether having an increasing number of people of many different races, ethnic groups and nationalities makes their country a better or worse place to live, relatively few said it makes their country better.

And in Greece, Italy, Hungary and Poland, at least four-in-ten said increasing diversity harms their country.

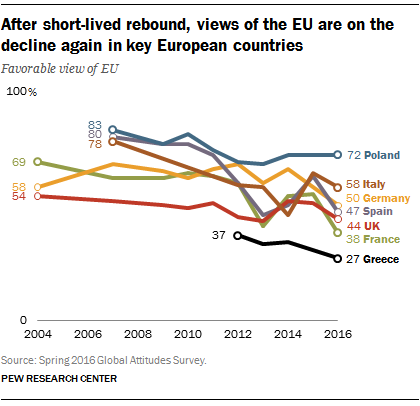

Europeans aren’t sure that establishment political institutions can help address these challenges. In several countries, traditional political parties are losing support while anti-establishment parties are gaining strength.

Often the populist challengers are coming from the ideological right, such as the National Front in France or the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands, but left-of-center populist parties have also emerged in Spain (Podemos) and Greece (Syriza). And the crisis of confidence isn’t just about political parties: Many have also lost faith in the European Union. In a number of member states, ratings for the EU are significantly lower than they were before the onset of financial crisis.

NOTE (April 2017): After publication, the weight for the Netherlands data was revised to correct percentages for two regions. The impact of this revision on the Netherlands data included in this blog post is very minor and does not materially change the analysis. For a summary of changes, see here. For updated demographic figures for the Netherlands, please contact info@pewresearch.org.