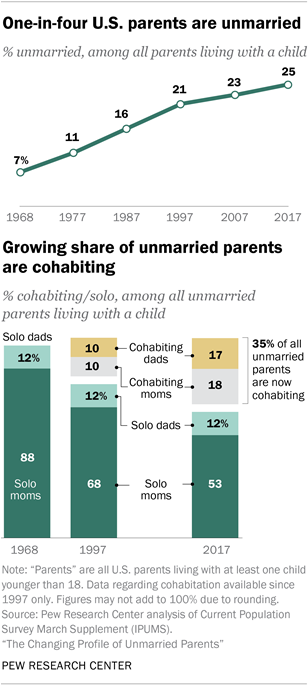

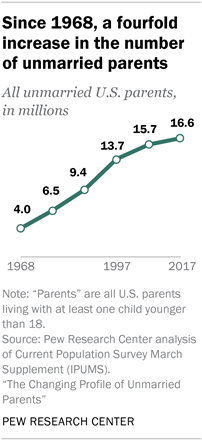

One-in-four parents living with a child in the United States today are unmarried. Driven by declines in marriage overall, as well as increases in births outside of marriage, this marks a dramatic change from a half-century ago, when fewer than one-in-ten parents living with their children were unmarried (7%).

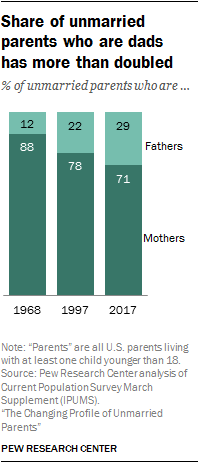

At the same time, the profile of unmarried parents has shifted markedly, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of Census Bureau data.1 Solo mothers – those who are raising at least one child with no spouse or partner in the home – no longer dominate the ranks of unmarried parents as they once did. In 1968, 88% of unmarried parents fell into this category. By 1997 that share had dropped to 68%, and in 2017 the share of unmarried parents who were solo mothers declined to 53%. These declines in solo mothers have been entirely offset by increases in cohabitating parents: Now 35% of all unmarried parents are living with a partner.2 Meanwhile, the share of unmarried parents who are solo fathers has held steady at 12%.

Due primarily to the rising number of cohabiting parents, the share of unmarried parents who are fathers has more than doubled over the past 50 years. Now, 29% of all unmarried parents who reside with their children are fathers, compared with just 12% in 1968.

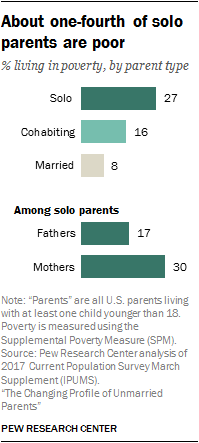

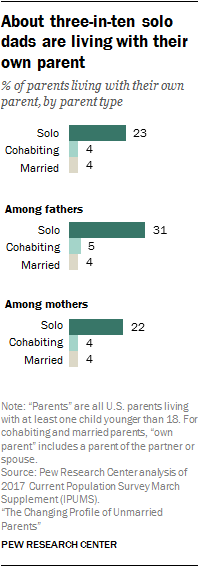

While it’s well-established that married parents are typically better off financially than unmarried parents, there are also differences in financial well-being among unmarried parents. For example, a much larger share of solo parents are living in poverty compared with cohabiting parents (27% vs. 16%).3 There are differences in the demographic profiles of each group as well. Cohabiting parents are younger, less educated and less likely to have ever been married than solo parents. At the same time, solo parents have fewer children on average than cohabiting parents and are far more likely to be living with one of their own parents (23% vs. 4%).

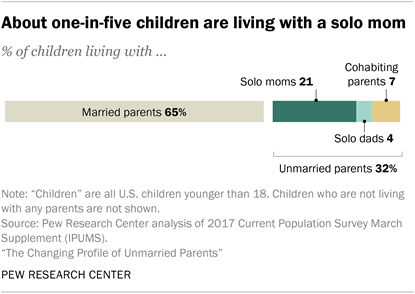

As the number of parents who are unmarried has grown, so has the number of children living with an unmarried parent. In 1968, 13% of children – 9 million in all – were living in this type of arrangement, and by 2017, that share had increased to about one-third (32%) of U.S. children, or 24 million. However, the share of children who will ever experience life with an unmarried parent is likely considerably higher, given how fluid U.S. families have become. One estimate suggests that by the time they turn 9, more than 20% of U.S. children born to a married couple and over 50% of those born to a cohabiting couple will have experienced the breakup of their parents, for instance. The declining stability of families is linked both to increases in cohabiting relationships, which tend to be less long-lasting than marriages, as well as long-term increases in divorce. Indeed, half of solo parents in 2017 (52%) had been married at one time, and the same is true for about one-third of cohabiting parents (35%).

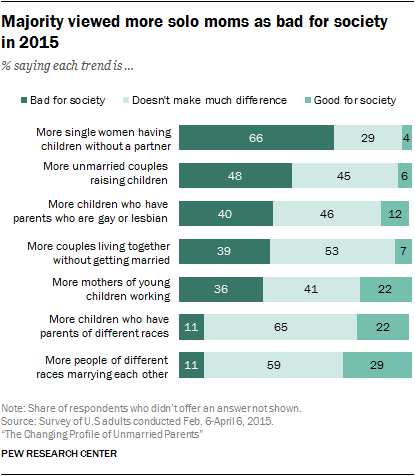

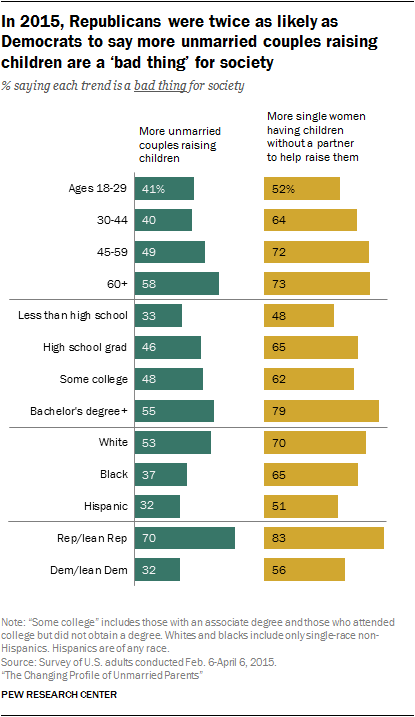

While it has become more common in recent decades, many Americans view the increase in unmarried parenthood – solo mothering especially – as a negative trend for society. In a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, two-thirds of adults said that more single women raising children on their own was bad for society, and 48% said the same about more unmarried couples raising children. Acceptance of unmarried parenthood tends to be particularly low among whites, college graduates, and Republicans. Even so, other data suggest a slight uptick in acceptance. In 1994, 35% of adults agreed or strongly agreed that single parents could raise children as well as two married parents, according to data from the General Social Survey; by 2012 the share who said as much had risen to 48%.

Declines in marriage and increases in nonmarital births have driven rise in unmarried parenting

The rise over the past half-century in the share of all U.S. parents who are unmarried and living with a child younger than 18 has been driven by increases in all types of unmarried parents. In 1968, only 1% of all parents were solo fathers; that figure has risen to 3%. At the same time, the share of all parents who are solo mothers has doubled, from 7% up to 13%. Since 1997, the first year for which data on cohabitation are available, the share of parents that are cohabiting has risen from 4% to 9%.

All told, more than 16 million U.S. parents with no spouse at home are now living with their child younger than 18, up from 4 million in 1968 and just under 14 million in 1997.

The growth in unmarried parenthood overall has been driven by several demographic trends. Perhaps most important has been the decline in the share of people overall who are married. In 1970, about seven-in-ten U.S. adults ages 18 and older were married; in 2016, that share stood at 50%. Both delays in marriage and long-term increases in divorce have fueled this trend. In 1968, the median age at first marriage for men was 23 and for women it was 21. In 2017, the median age at first marriage was 30 for men and 27 for women. At the same time, marriages are more likely to end in divorce now than they were almost half a century ago.4 For instance, among men whose first marriage began in the late 1980s, about 76% were still in those marriages 10 years later, while this figure was 88% for men whose marriages began in the late 1950s.

Not only are fewer Americans getting married, but it’s also becoming more common for unmarried people to have babies. In 1970 there were 26 births per 1,000 unmarried women ages 15 to 44, while that rate in 2016 stood at 42 births per 1,000 unmarried women. Meanwhile, birthrates for married women have declined, from 121 births per 1,000 down to about 90. As a result, in 2016 four-in-ten births were to women who were either solo mothers or living with a nonmarital partner.

Increases in the number of cohabiting parents raising children have also contributed to the overall growth in unmarried parenthood. In 1997, the first year for which data on cohabitation are available, 20% of unmarried parents who lived with their children were also living with a partner.5 Since that time, the share has risen to 35%.

This trend has boosted the overall share of unmarried parents who are fathers. In 1968, just 12% were fathers; by 1997 the share had risen to 22%, and in 2017 it stood at 29%. At the same time, solo parents remain overwhelmingly female: 81% of solo parents in 2017 were mothers, as were 88% in 1968.

For solo and cohabiting parents, very different demographic profiles

As a result of the rise and transformation of unmarried parenthood in the U.S., significant demographic differences now exist not only between married and unmarried parents, but among unmarried parents. And in some cases, even among solo or cohabiting parents, dramatic differences have emerged between fathers and mothers.

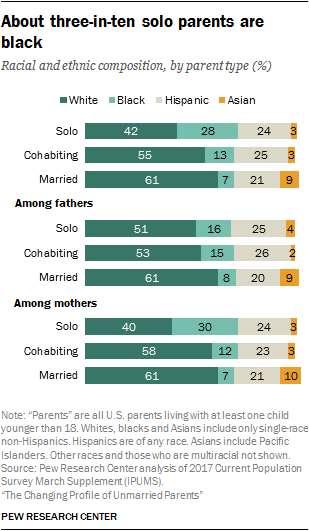

Compared with cohabiting parents, solo parents are more likely to be female and black

Because cohabiting parents are overwhelmingly opposite-sex couples, they are about evenly split between men and women.6 Among solo parents, however, the vast majority (81%) are mothers; only 19% are fathers. This gender difference is even more pronounced among black solo parents: 89% are mothers and just 11% are fathers.

Overall, there are significant differences in the racial and ethnic profiles of solo and cohabiting parents. Among solo parents, 42% are white and 28% are black, compared with 55% of cohabiting parents who are white and 13% who are black.

These gaps are driven largely by racial differences among the large share of solo parents who are mothers. Solo moms are more than twice as likely to be black as cohabiting moms (30% vs. 12%), and roughly four times as likely as married moms (7% of whom are black). Four-in-ten solo mothers are white, compared with 58% of cohabiting moms and 61% of married moms.

There are virtually no racial and ethnic differences in the profiles of solo and cohabiting fathers. About half of each group are white, roughly 15% are black, about one-fourth are Hispanic and a small share are Asian. Married fathers, however, are more likely than unmarried fathers to be white (61% are) and less likely to be black (8%).

Only 3% of solo or cohabiting parents are Asian, compared with 9% of married parents. A similar pattern emerges among both Asian fathers and mothers.

Among all parents, Hispanics are about equally represented across all three family types – solo, cohabiting and married parents – with no large differences among Hispanic mothers and Hispanic fathers.

Solo parents are older, more educated and more likely to have been married than cohabiting parents

Cohabiting parents are younger on average than solo or married parents. Their median age is 34 years, compared with 38 among solo parents and 40 among married parents.

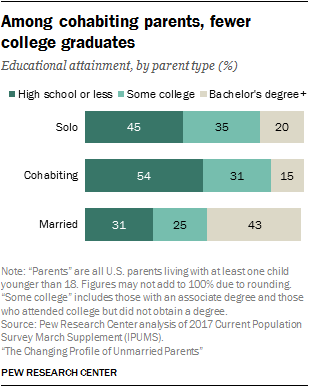

Cohabiting parents have lower levels of educational attainment than other parents, due at least in part to their relative youth. Just over half (54%) of cohabiting parents have a high school diploma or less education, compared with 45% of solo parents and 31% of married parents. At the other end of the spectrum, 15% of cohabiting parents have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with 20% of solo parents. Married parents, in contrast, are more than twice as likely as unmarried parents to have a bachelor’s degree (43% do), reflecting the growing gap in marriage across educational levels.

Cohabiting fathers, in particular, have lower levels of education than their solo counterparts. Roughly six-in-ten cohabiting fathers (61%) – versus 51% of solo fathers – have a high school diploma or less education. Conversely, just 12% of cohabiting fathers have a bachelor’s degree, while 21% of solo fathers do. There are no large educational differences in the profile of solo and cohabiting mothers.

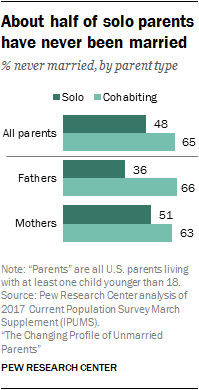

The relative youthfulness of cohabiting parents also contributes to the high share (65%) that have never married, meaning that most children with cohabiting parents were born outside of marriage. In contrast, about half (48%) of solo parents have never been married.

Cohabiting mothers and fathers are about equally likely to have never married. Among solo parents, however, mothers are more likely than fathers to have never been married (51% of solo mothers vs. 36% of solo fathers), suggesting that solo mothers and solo fathers may take somewhat different paths to unmarried parenthood.

Three-in-ten solo mothers are living in poverty

Despite the fact that cohabiting parents are younger and less educated than solo parents, they are still far less likely to be poor. All told, 16% of unmarried parents living with a partner are living below the poverty line, while about one-fourth (27%) of solo parents are. In comparison, just 8% of married parents are living in poverty.7

Among solo parents, mothers are almost twice as likely as fathers to be living below the poverty line (30% vs. 17%), but poverty rates for cohabiting parents don’t differ among mothers and fathers.

Solo and cohabiting parents are about equally likely to be employed (72% and 73%, respectively). However, a majority (53%) of cohabiting parents are in a dual-earner household, which accounts for some of the differences in poverty levels between the two groups.

Roughly one-in-four solo parents are living with their own parent

Not only do solo and cohabiting parents differ in terms of their demographic and economic profiles, but their household situations are different as well. Solo parents don’t have a partner at home, but they are far more likely than their married and cohabiting counterparts to be living with at least one of their own parents – 23% do. This is particularly common among solo dads, 31% of whom are residing with at least one of their parents. Among solo moms, this figure stands at 22%. In comparison, only 4% of cohabiting parents are living with at least one of their own or their partner’s parents – the same share as among their married counterparts.

While the role of these grandparents cannot be determined for certain from this data, prior Pew Research Center analyses of 2011 Census Bureau data suggest that many could be playing an important role as caregiver to any grandchildren in the household. In fact, a 2013 analysis found that among all grandparents who lived with at least one grandchild at the time (whether the child’s parent was present or not), about four-in-ten (39%) said they were responsible for most of that grandchild’s basic needs.

Cohabiting parents have more children, on average, than solo parents do. Just over half (53%) of cohabiting parents have more than one child at home, compared with 44% of solo parents. Among solo parents, though, moms are more likely than dads to have multiple kids at home – almost half (46%) do, while 35% of solo fathers are raising more than one child.

Cohabiting parents are also more likely than their solo counterparts to have young children at home. This is linked to the fact that they themselves tend to be younger. Fully 60% of cohabiting parents are living with at least one child younger than 6, compared with 37% of solo parents and 44% of married parents. Among solo parents, mothers are much more likely than fathers to have a preschool-age child in the house. About four-in-ten (39%) do, compared with 26% of dads.

Public views of unmarried parenthood

As unmarried parenthood has grown more common in the U.S., the public has become somewhat more accepting of it, though large shares say that this trend is bad for society.

A 2015 Pew Research Center survey found that the trends toward more single women having children and more unmarried couples raising children were seen as relatively more harmful to society, compared with other changes in American families.8

Americans were far more likely to express a negative view regarding the rise of single mothers than any other trend: Two-thirds (66%) said that more single women having children was bad for society, and just 4% said this trend was good for society (the remaining 29% said the trend doesn’t make much difference). At the same time, about half (48%) said more unmarried couples raising children was bad for society, while just 6% said it was good for society and 45% said it didn’t make much difference.

By comparison, other family trends were seen as less negative, though substantial shares saw some of those trends as bad for society. For example, four-in-ten adults said that the growing number of children who have parents who are gay or lesbian was bad for society, and a similar share (39%) said the same about more couples living together without being married. When it came to more mothers of young children working outside the home, 36% said this was a bad thing, but a sizable minority (22%) saw it as a good thing. Relatively few Americans (11%) said the trends toward more children with parents of different races and more interracial marriages were bad for society; at least twice as many viewed each of these trends as good for society (22% and 29%, respectively). In each case, majorities or pluralities of the public said these trends didn’t make much of a difference for society.

Views on unmarried parents vary widely by party affiliation. The overwhelming majority (83%) of Republicans and independents who lean to the Republican Party said that more single women having children without a partner is bad for society; 56% of Democrats and those who lean Democratic said the same. Partisan differences were even wider on attitudes about unmarried parents raising children together: While 70% of Republicans saw this as bad for society, about half as many Democrats (32%) said the same.

Older Americans and those with higher levels of education were especially likely to view these trends as bad for society.

There were racial and ethnic gaps as well, particularly on views about unmarried couples raising children: 53% of whites viewed more unmarried couples raising children as a bad thing, compared with 37% of blacks and 32% of Hispanics.

Other data suggest there has been some softening in views towards unmarried parenthood. In 2012, 48% of adults agreed or strongly agreed that single parents could raise children as well as two parents can, according to the General Social Survey. This marked a slight increase from 1994, when just 35% said as much. At the same time, the share of people who disagreed or strongly disagreed that single parents could raise children as well as two parents ticked down, from 48% to 41%.

About the data

This report is based primarily on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s March Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS), also known as the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). The survey produces a nationally representative sample of the non-institutionalized U.S. population. The analysis in this report starts with 1968, the first year for which ASEC data are publicly available.

Because the CPS is based on households, only parents who are living with at least one of their children younger than 18 are included in this analysis. Prior Pew Research Center analysis indicates that 17% of fathers of children younger than 18 are living apart from all of these children, and fathers living apart from their children have different characteristics than those who live with their children.

The CPS does not explicitly ask about custody arrangements, but any parent whose child lives with them most of the time is counted as “living with” that child. In cases where custody is split 50-50, the parent is counted as “living with” their child if the child is present at the time of the interview.

Throughout this report, “fathers,” “mothers” and “parents” refer to people who are living with their child younger than 18 years, and to people who are their spouses or partners. These include both biological parents and parents who are not biologically linked to the children in their family.

The Current Population Survey (CPS) does not explicitly ask about custody arrangements, but any parent whose child lives with them most of the time is counted as “living with” that child. In cases where custody is split 50-50, the parent is counted as “living with” their child if the child is present at the time of the interview.

All cohabiting parents – meaning parents who are living with a partner to whom they are not married – are identified in analyses since 2007. From 1995 to 2006, the CPS only collected data on cohabitation among unmarried household heads, so only those respondents and their partners are counted as cohabiting. This leads to an undercount of cohabiting parents for those years. The size of this undercount prior to 2007 can’t be determined, but in 2007 the vast majority (93%) of all cohabiting parents were either the head of household or the partner of the head. Prior to 1995, cohabiting couples were not identified in the CPS.

All same-sex couples, regardless of their marital status, are classified as “cohabiting,” since that is the convention used in the CPS. For more on same-sex parents, see “LGB Families and Relationships: Analyses of the 2013 National Health Interview Survey.”

The small share of parents who are married but not living with a spouse or partner are classified as “solo parents,” along with those who are neither married nor living with a partner.

“Some college” includes those with an associate degree and those who attended college but did not obtain a degree. “High school” includes those who have a high school diploma or its equivalent, such as a General Education Development (GED) certificate.

Whites, blacks and Asians include only single-race non-Hispanics. Hispanics are of any race. Asians include Pacific Islanders.