For most of its first half-century, the European Union consisted almost entirely of countries from Western Europe, such as France, Italy and Belgium. That changed in 2004, when the EU expanded to include some former Soviet bloc countries in Central and Eastern Europe, including Hungary, Poland and Estonia.

While the EU has integrated its new member states into its governing structures, there are some significant differences in public attitudes between its Western European countries and its Central and Eastern European countries, according to a new analysis of Pew Research Center surveys conducted between 2015 and 2017.

Specifically, adults in the EU’s Central and Eastern European states tend to be less likely than those in the EU countries of Western Europe to say they would welcome Muslims or Jews into their families or neighborhoods, and they are less likely to favor same-sex marriage. At the same time, the Central and Eastern Europeans are more likely than the Western Europeans to view Christianity as an important component of their national identity, and to express higher levels of religious commitment.

Here are six key findings from the analysis, based on surveys of 24 EU countries, including 13 in Western Europe and 11 in Central and Eastern Europe. The analysis stems from a new Pew Research Center report about differences in attitudes between Western and Eastern Europeans more broadly.

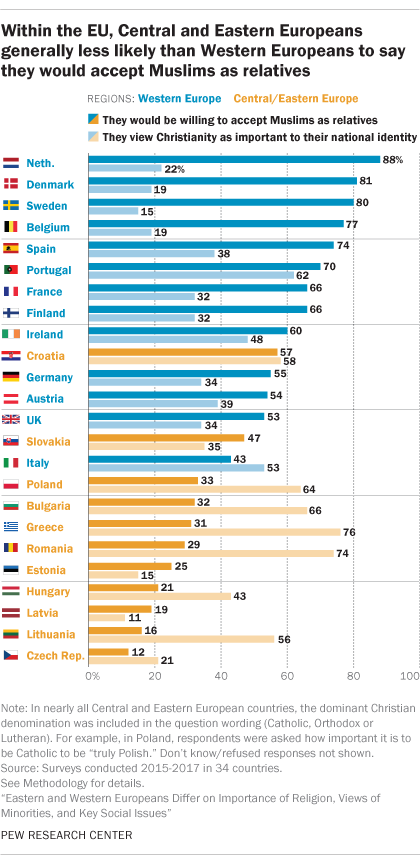

Central and Eastern Europeans in the EU are less willing than Western Europeans in the EU to say they would accept Muslims or Jews as members of their family or as neighbors. In nearly all of the Central and Eastern European countries surveyed, fewer than half of adults say they would be willing to accept Muslims into their family, including 29% who say this in Romania and 32% in Bulgaria. Meanwhile, in most of the surveyed Western European countries, more than half of adults say they would accept a Muslim into their family, including 66% who say this in Finland and 74% in Spain. The same general pattern holds when Europeans are asked about accepting Jews as family members or neighbors.

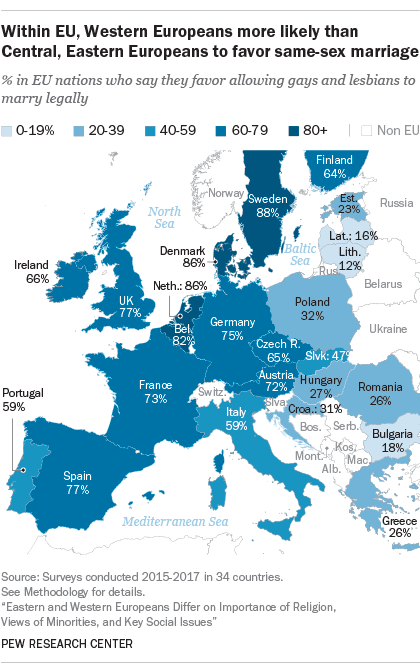

Majorities in all of the surveyed Western European countries favor same-sex marriage, while majorities in almost all of the Central and Eastern European countries oppose it. For example, 88% of adults in Sweden and 75% in Germany say they favor or strongly favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally. By contrast, 74% of Romanians and 79% of Bulgarians oppose or strongly oppose allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally. This split in attitudes is reflected in the laws of the two regions: While most Western European countries in the EU allow same-sex marriage, it is prohibited from taking place in most of the bloc’s Central and Eastern European nations.

Central and Eastern Europeans in the EU are more likely than Western Europeans in the EU to view religion as a central component of their national identity. In roughly half of the Central and Eastern European countries surveyed, majorities say that being Christian – whether Catholic, Orthodox or Lutheran – is an important element of being “truly Lithuanian,” “truly Polish,” etc. In Romania and Bulgaria, for example, 74% and 66% say, respectively, that it is “very” or “somewhat” important to be a Christian to truly share the national identity. This sentiment is considerably less prevalent in the Western European countries surveyed, where majorities in most countries say that being Christian is a not very or not at all important part of the national identity.

The EU’s Central and Eastern Europeans are more likely than its Western Europeans to say their own culture is superior to others. The Center asked respondents if they agree with the statement, “Our people are not perfect, but our culture is superior to others.” Of the five EU countries where more than half the respondents say they agree with this statement, all are located in Central and Eastern Europe: Greece (89%), Bulgaria (69%), Romania (66%), Poland (55%) and the Czech Republic (55%). In addition, people in Central and Eastern European countries are more likely than those in Western Europe to emphasize certain nativist elements of national identity. For instance, roughly eight-in-ten Poles say that being born in Poland (82%) and having ancestry there (83%) are important to being truly Polish, while far fewer Germans (48% and 49%, respectively) say this about being truly German.

More people identify as Christian than anything else in 20 of the 24 EU countries surveyed, but the share of Christians tends to be higher in Central and Eastern Europe than in the West. For instance, 98% of adults identify as Christians in Romania, compared with 71% in Germany. Moreover, there has been a significant decline in the share of people who identify as Christian in the EU’s Western European countries. In Spain, for example, 66% of respondents currently identify as Christian, compared with 92% who say they were raised Christian. By contrast, the Christian share of the population within the EU’s Central and Eastern European countries has largely remained stable.

Western Europeans in the EU are less religiously committed than their Central and Eastern European counterparts. On balance, adults in Western Europe are less likely than those in Central and Eastern Europe to say that religion is very important in their lives, that they pray every day, and that they attend religious services at least monthly. For example, just 11% in Germany and 10% in the United Kingdom say that religion is very important in their lives, compared with 55% of adults in Greece and 50% in Romania. That said, Europeans across the continent are, by a number of measures, generally less religious than adults in other regions surveyed by Pew Research Center, such as sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the United States.