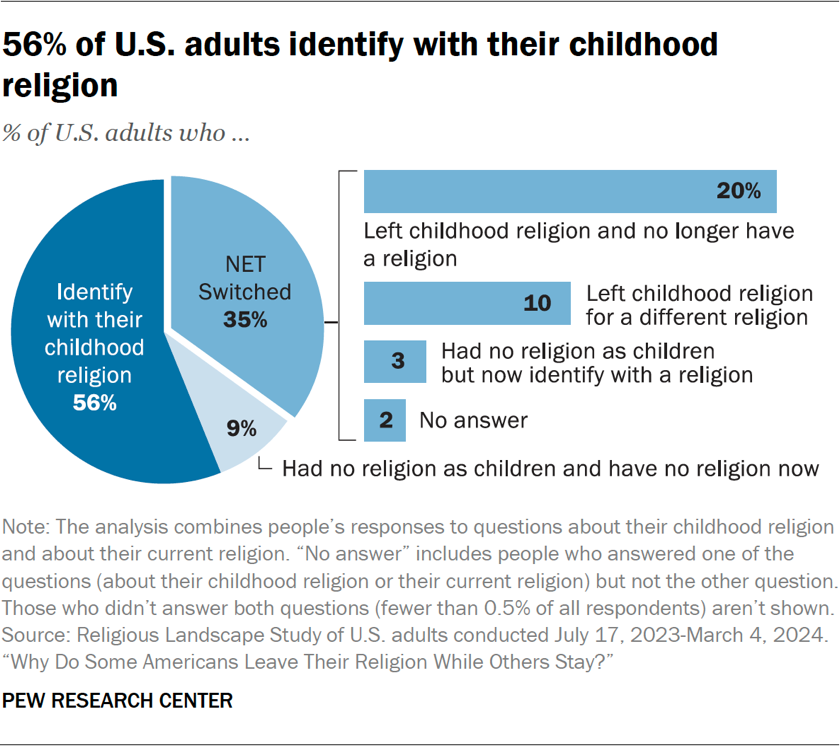

Many U.S. adults (35%) have moved on from the religion of their youth. Yet most Americans have not, including a majority – 56% – who still identify with their childhood religion. Another 9% weren’t raised in a religion and still don’t have one today.

This Pew Research Center report looks at the choices behind these decisions: why some people continue to identify with their childhood religion, why others have decided to leave it, and why others don’t identify with any religion at all.

The findings about how many people switch religions come from our U.S. Religious Landscape Study (RLS) conducted in 2023-24. But to dig deeper into the reasons people give for switching or staying, we conducted a follow-up survey in May 2025.

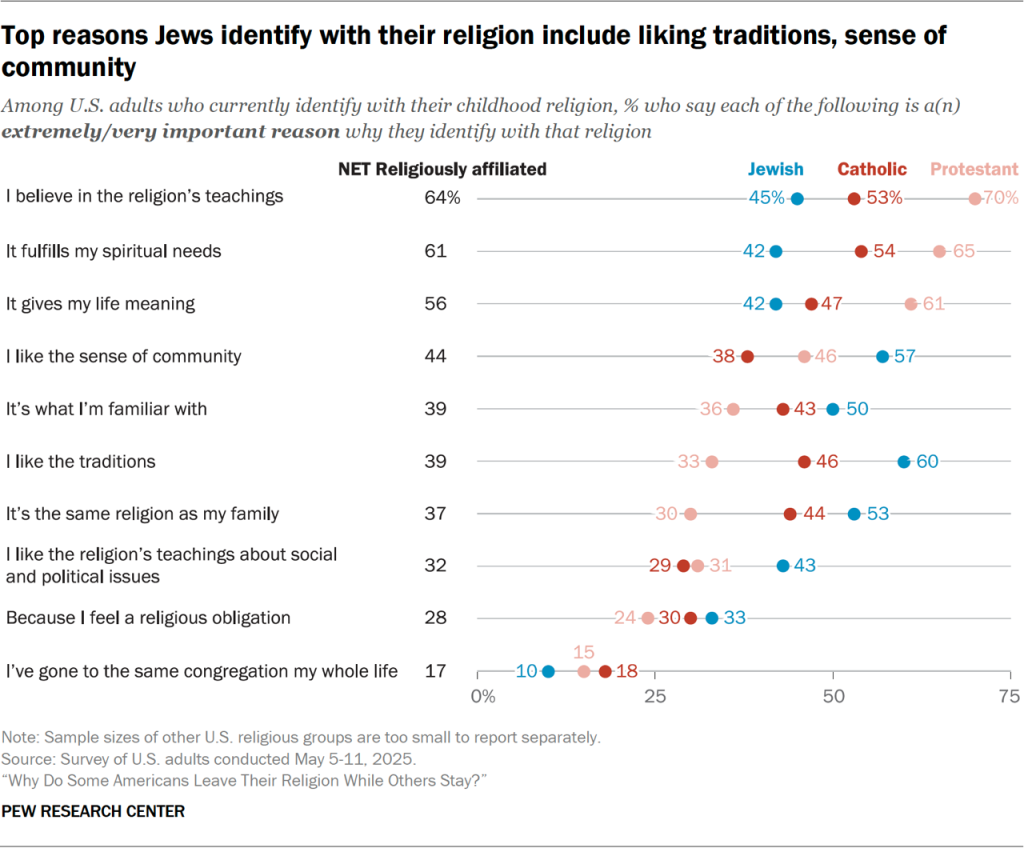

The follow-up survey shows that most U.S. adults who still identify with their childhood religion credit the following as extremely or very important reasons:

- They believe the religion’s teachings (64% of adults who identify with their childhood religion say this).

- Their religion fulfills their spiritual needs (61%).

- Their religion gives their life meaning (56%).

Fewer say that other reasons – such as a sense of community (44%), familiarity (39%), traditions (39%), or the religion’s teachings on social and political issues (32%) – are extremely or very important reasons why they continue to identify with their childhood religion as adults.1

Among Protestants who have held onto their religious identities, 70% cite belief in their religion’s teachings as a key reason why they are Protestant today. Most lifelong Protestants also say they are Protestants today because their faith meets their spiritual needs and gives their life meaning.2

Among Catholics who have held onto their religious identities, 54% say a key reason they are Catholic today is because it fulfills their spiritual needs, 53% cite belief in the religion’s teachings, and 47% say it’s because it gives their life meaning.

Lifelong Jews most commonly mention a somewhat different set of reasons for why they are Jewish. Among U.S. adults who were raised Jewish and still identify as Jewish by religion, 60% say liking the traditions is an extremely or very important reason they are Jewish, and 57% cite liking the sense of community. About half of Jews say they are Jewish because it’s their family religion and/or because it’s something they’re familiar with.

(There were not enough respondents from other groups – such as people raised Muslim who still identify as Muslim, or people raised Buddhist who are still Buddhist – for us to be able to analyze their responses separately.)

Americans’ choices to stay in or leave their childhood religion also are tied to their religious upbringing, their age and their political leanings.

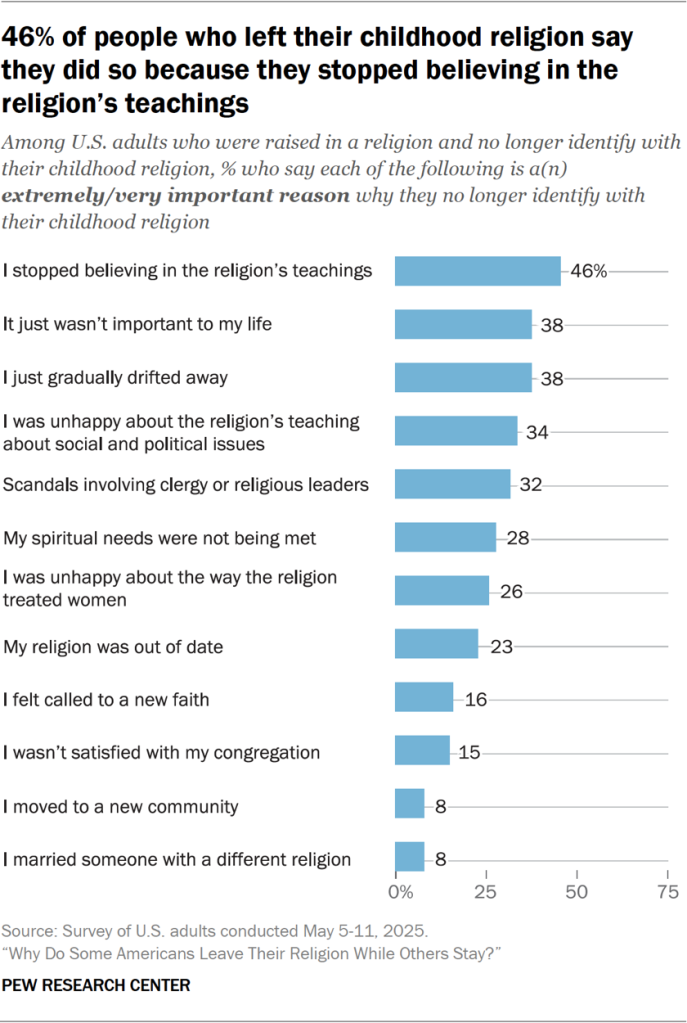

Reasons people say they left their childhood religion

We asked a different group of Americans, those saying they had left their childhood religion, to evaluate the importance of various factors that may have led them to leave. This group includes Americans who were raised in one religion and have switched to another religion (10% of U.S. adults) as well as those who no longer identify with any religion (20%).

Americans who’ve left their childhood religion most commonly cite the following as extremely or very important reasons behind their decision:

- They stopped believing in the religion’s teachings (cited by 46% of people who were raised in a religion and have left that religion).

- It wasn’t important in their life (38%).

- They just gradually drifted away (38%).

About a third of people in this group say their religion’s teachings about social and political issues (34%) or scandals involving clergy or religious leaders (32%) were important reasons for leaving the religion in which they were raised.3

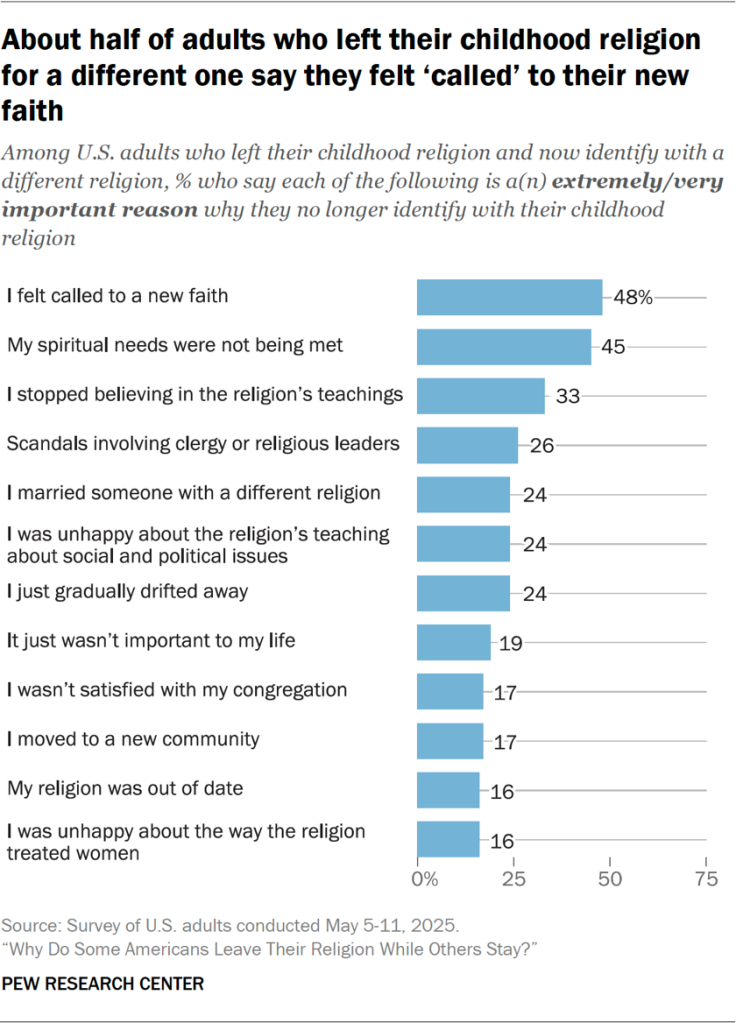

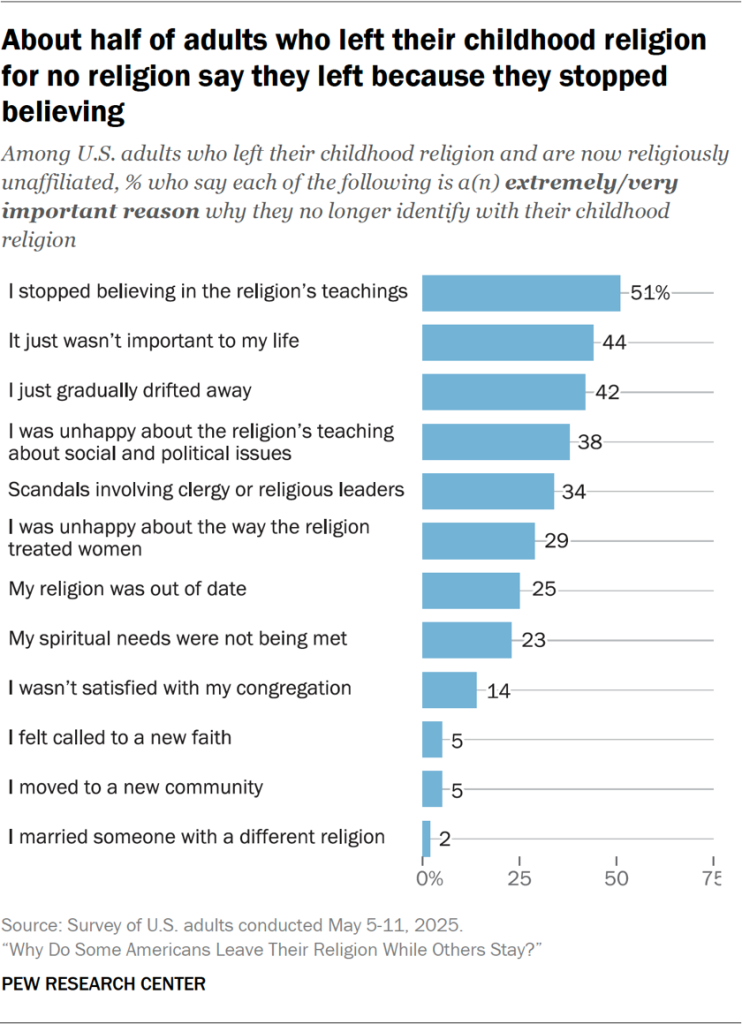

Among people who have left their childhood religion, those who now identify with another religion tend to give different reasons than those who are now religiously unaffiliated.

For example, 48% of those who switched into another religion say feeling “called to a new faith” was an extremely or very important reason for leaving their childhood religion. A similar share of switchers to another religion (45%) say the religion in which they grew up did not meet their spiritual needs.

On the other hand, switchers who are now “nones” are most likely to cite having stopped believing in the religion’s teachings as an important reason for having left their childhood religion (51%). Many also say their childhood religion just wasn’t important in their life (44%) or they “gradually drifted away” from it (42%).

Reasons people say they are religiously unaffiliated

We directed a third set of questions to adults who are religiously unaffiliated (sometimes called religious “nones”). This group – which consists of people who answer a question about their present religion by saying they are atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” – makes up 29% of U.S. adults, according to our 2023-24 Religious Landscape Study.

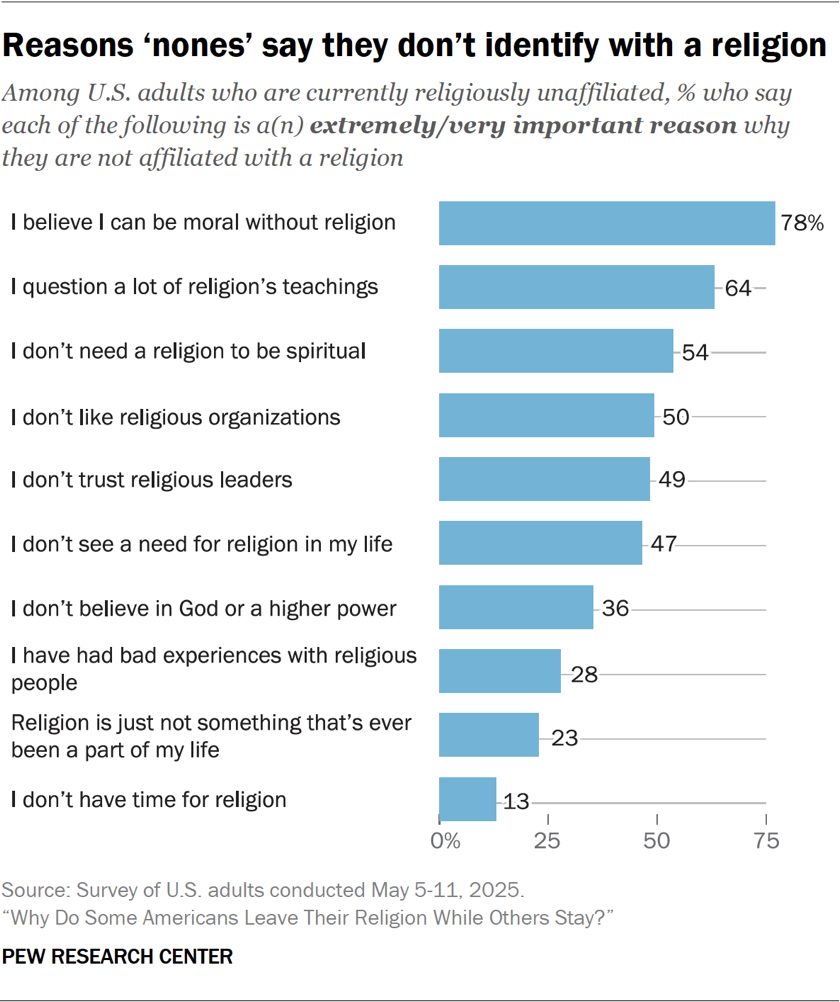

We asked the “nones” in our survey to evaluate the importance of several possible reasons why they don’t identify with a religion. The reasons they most commonly describe as extremely or very important include:

- They believe they can be moral without religion (78%).

- They question a lot of religious teachings (64%).

- They don’t need religion to be spiritual (54%).

Additionally, about half of the religiously unaffiliated Americans surveyed cited not liking religious organizations (50%) or not trusting religious leaders (49%) as extremely or very important reasons.

The survey also asked “nones” if, in their own words, there were any other important reasons why they don’t identify with a religion. Some expressed the view that religion is harmful (6% of all “nones”) or said they believe in God or scripture or are otherwise open to religion, but don’t feel the need to affiliate (6%). Refer to the topline for the full list of coded responses.

Our study also found that 3% of U.S. adults weren’t raised with a religion but now identify with one. (Read about why some childhood “nones” say they joined a religion as adults in our later report chapter.)

These are among the key findings of a new analysis based on two Pew Research Center surveys: a survey of 8,937 U.S. adults conducted May 5-11, 2025, on our American Trends Panel; and the 2023-24 Religious Landscape Study, which was conducted from July 17, 2023, to March 3, 2024, among 36,908 U.S. adults.

We got our data about religious switching from two separate questions: “What is your present religion, if any?” and “In what religion were you raised, if any?” On each of these questions, we offered respondents the same list of options: Protestant, Catholic, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon), Orthodox Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, agnostic, something else, or “nothing in particular.” Those who said they are atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” were combined to create the religiously unaffiliated category.

We count respondents who give the same answer to both questions as people who have not switched religions. Those who gave different answers are counted as having switched. Switchers include, for example, people who said they were raised Protestant and are now religiously unaffiliated; or who said they were raised Jewish and now consider Buddhism to be their religion; or who said they were not raised in any religion and are now Catholic.

However, this analysis does not count people who changed from one Protestant denomination to another as having switched religions. For example, someone who was raised Methodist and is now Baptist is not considered in this report to have switched religions. Similarly, someone who grew up as an atheist but now identifies as agnostic is not counted as having switched, since both of those identities are part of the religiously unaffiliated category.

The rest of this Overview looks at:

- People raised in a religion: Factors in whether they have stayed or left

- People not raised in a religion: Factors in whether they have joined one

- The timing of religious switching

People raised in a religion: Factors in whether they have stayed or left

Another way to examine why people leave or stay in their childhood religion is through an analysis of how various factors – such as religious upbringing and social and demographic traits – may be tied to their religious identity as adults.

Religious upbringing

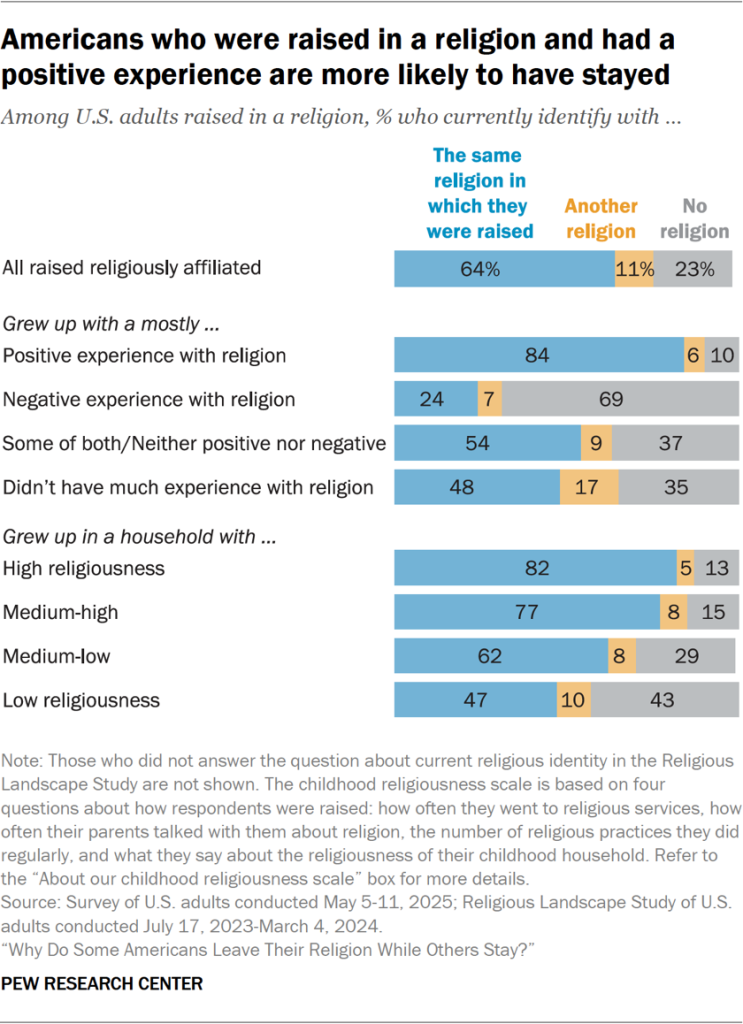

Most U.S. adults (86%) were raised in a religion. Our data shows that the nature of their religious experiences as children – that is, whether they were mostly positive or negative – plays a significant role in whether they stay in their childhood religion as adults.

For example, 84% of Americans who were raised in a religion and who had a mostly positive childhood experience with religion still identify with that religion as adults. Just 10% of people who grew up in a religion and had a positive childhood experience with it are “nones” today, while 6% identify with a different religion than the one they were raised in.

In sharp contrast, 69% of those who grew up in a religion and had a negative experience with it no longer identify with any religion at all. Far fewer (24%) still identify with their childhood religion, and 7% identify with a different religion.4

The survey also finds that adults raised in a religion who grew up in highly religious households are more likely to have remained in their childhood religion (82%) than those who grew up in households with medium-high (77%), medium-low (62%) or low levels of religiousness (47%), as categorized on our religiousness scale.

Social and demographic traits

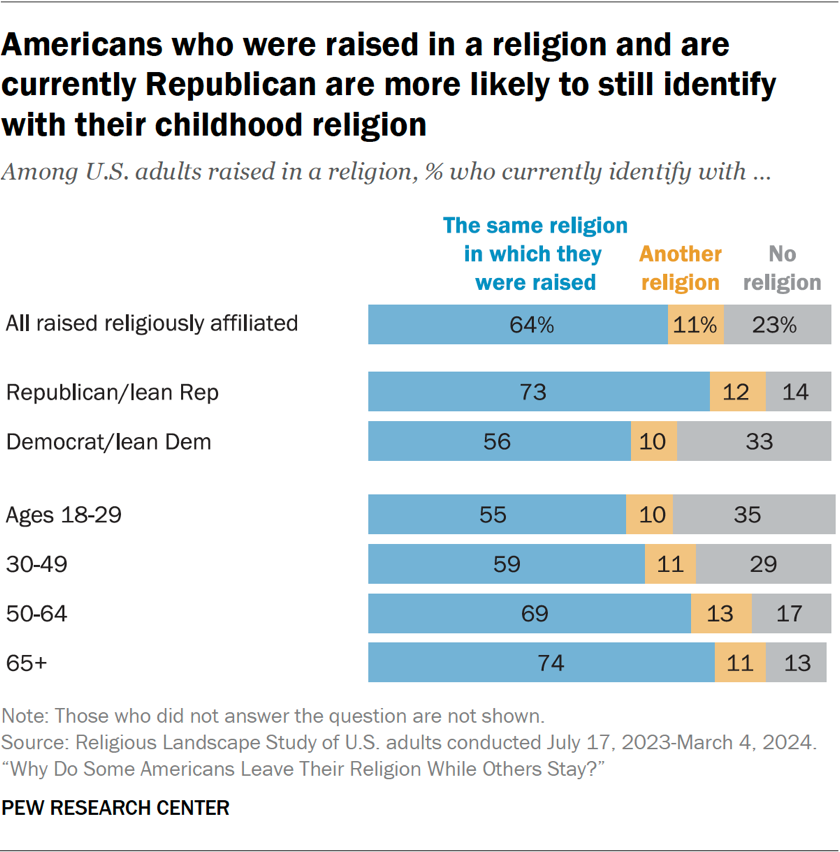

Among U.S. adults who were raised in a religion, 73% of Republicans and independents who lean toward the Republican Party still identify with the religion in which they were raised, compared with 56% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

Meanwhile, Democrats who were raised in a religion are more likely to be religious “nones” today compared with Republicans who were raised in a religion.

These patterns also differ by age. Among adults ages 65 and older who were raised in a religion, 74% still identify with that religion, while 11% identify with a different religion than the one they were raised in, and 13% do not identify with any religion. On the other hand, among adults under 30, 55% still identify with their childhood religion, while 10% now identify with another religion, and 35% are not affiliated with any religion.

Retention rates by religious group

When it comes to retention rates, Americans who were raised as Hindus (82%), Muslims (77%) and Jews (76%) are among the most likely to have remained in their childhood religion. Additionally, 73% of those raised without a religious affiliation have remained unaffiliated as adults, and 70% of people who were raised as Protestants still identify that way today. By comparison, retention rates are much lower among Catholics (57%), Latter-day Saints (54%) and Buddhists (45%).

Many U.S. adults who have left their childhood religion have become “nones.” But 14% of Americans raised Catholic are now Protestant. And 11% of those raised as Buddhists or as Latter-day Saints now identify as Protestants. (For more detail, read the chapter on religious switching in our 2023-24 Religious Landscape Study report.)

People not raised in a religion: Factors in whether they have joined one

Overall, 13% of all U.S. adults say they were raised with no religious affiliation. Most of them – 9% of all U.S. adults – were raised as “nones” and are still “nones.” But 3% of American adults were raised as “nones” and now identify with a religion.

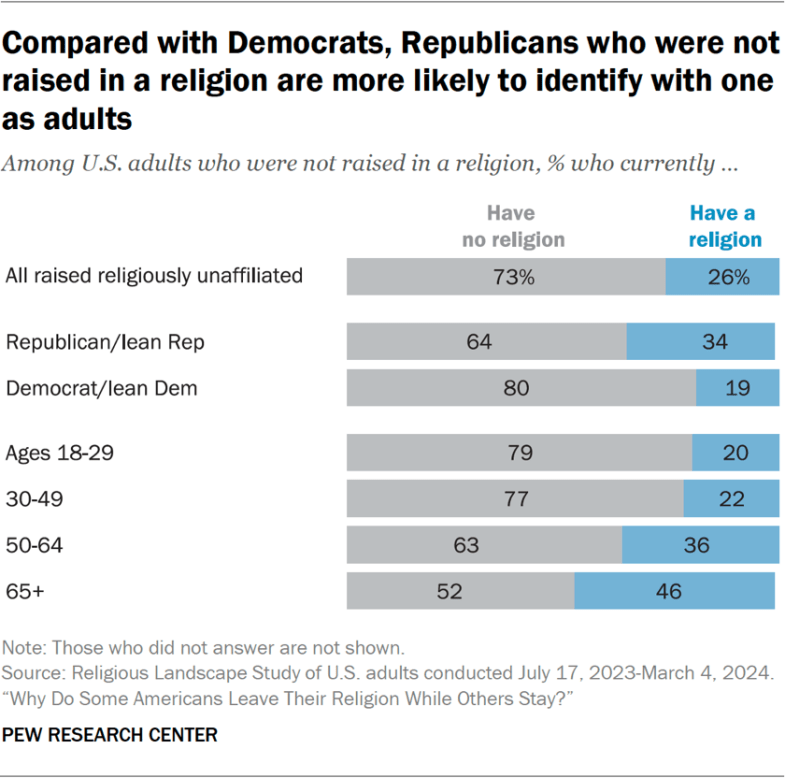

About three-quarters (73%) of people who grew up as “nones” remain religiously unaffiliated as adults, while 26% identify with a religion today.

In general, we find that Republicans who were raised as “nones” are more likely than Democrats who were raised as “nones” to identify with a religion as adults. That said, a majority of Republicans who grew up as “nones” have retained this identity (64%).

We also find that older people who were raised as “nones” are more likely than younger people who were raised that way to say they now identify with a religion. For example, 46% of adults ages 65 and older who were raised with no religious affiliation now identify with a religion, compared with 20% of adults under 30 who were raised as “nones.” (It’s also true, of course, that older “nones” have lived longer than younger “nones,” so they’ve had more time to change their religious identities.)

The timing of religious switching

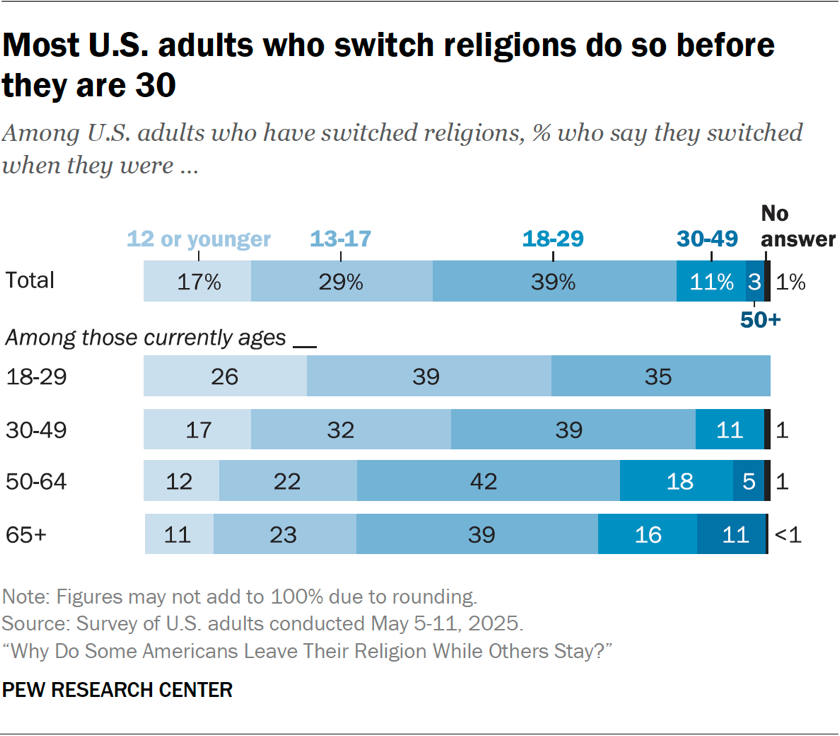

Americans who switch religions tend to do so early in life: 85% who have switched say they did so by the age of 30. This includes 46% who switched as children or teenagers.

Even the oldest adults in our survey, Americans ages 65 and older, are far more likely to say they switched religions before turning 30 than afterward.

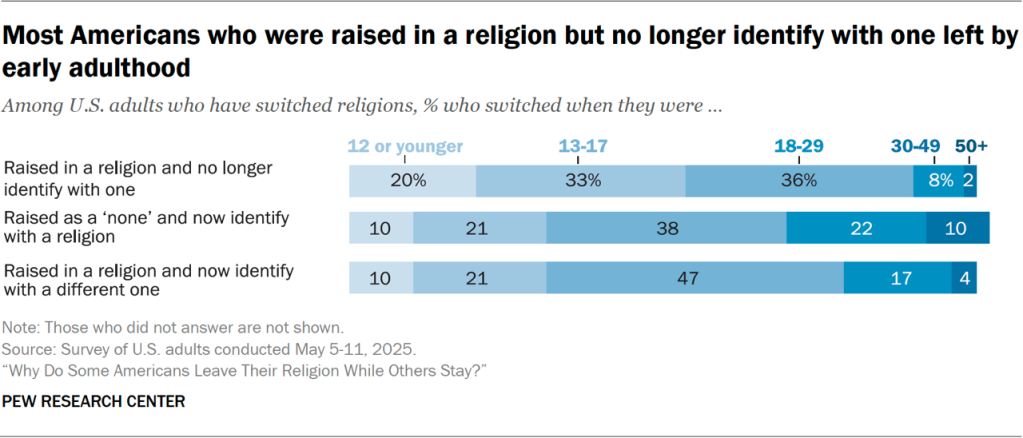

People who have switched from a childhood religion to having no religion tend to have made that change earlier in life than people who have switched from one religion to another, or from having no religion to having a religion.

For example, 53% of people who were raised in a religion but are now religious “nones” say they left their childhood religion before turning 18, and another 36% left prior to turning 30.

By comparison, about three-in-ten people who have switched from one religion to another, or who went from not having a religion to having one, made those moves before age 18.

For more, jump to the following chapters: