One distinguishing characteristic about the campaign conversation on Twitter is the sheer volume of opinions or assertions carried in the 140-character format.

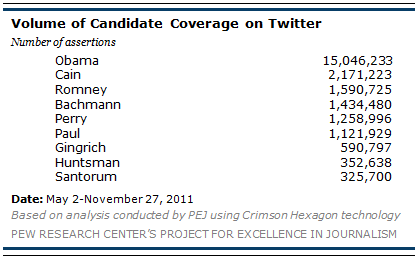

Consider that there were more than 15 million assessments offered about President Obama between May 2 and November 27, almost 2.2 million about Cain, and almost 1.6 million about Romney. Gingrich was the subject of far fewer, just under 600,000, which puts him ahead of only Huntsman and Rick Santorum.

Another characteristic of the conversation on Twitter is the intensity of the discourse. In most cases, whatever the tone of the conversation about a candidate was in blogs, it was amplified on Twitter-in both the negative and positive directions.

In the blogosphere, for instance, negative opinions about Bachmann outnumbered positive opinions by 26 percentage points. On Twitter, that gap leaped to 51 percentage points. The same pattern was equally clear in the case of Perry. The discourse on blogs was tough enough-negative assertions exceeded positive ones by 25 percentage points. But on Twitter, that margin grew to 40 points. Similarly, in varying degrees, three other candidates whose negatives outweighed their positives on blogs-Romney, Obama and Santorum-also saw that gap grow on Twitter.

For Paul, the converse was true. He enjoyed the most flattering conversation on blogs, where positive assertions outnumbered negative ones by 32 percentage points. But that gap stretched even further-to 40 percentage points-on Twitter.

That intensity gap was connected to another difference about Twitter. The data find that it is less neutral-far less so than news coverage, but even less neutral than blogs. Only two candidates, Romney and Gingrich, had a higher percentage of neutral assessments on Twitter (40% for Romney, 38% for Gingrich) than in blogs (32% for Romney, 37% for Gingrich).

For most candidates, however, the percentage of neutral statements was markedly smaller on Twitter than in blogs and much smaller than in the news coverage, where neutral assessments comprised the largest component of each candidate’s coverage.

There may be several explanations for why Twitter content is more voluminous, more intense and less neutral. One is brevity. Capped at 140 characters, there isn’t much room for qualification and nuance. Another is the ease with which a provocative statement can be passed on. One Tweet can be amplified and multiplied many times over by having Twitter users retweet the original message.

When it came to the volatility of a candidate’s coverage-how much the tone of that coverage varied from week to week-the news media produced the narrative that was most likely to change and bounce between positive and negative.

In blogs the narrative changed relatively little regardless of what was occurring in the campaign.

On Twitter, there was considerably more volatility within candidate narratives than in blogs.

Perry, for example, had negative opinions ranging from 27% one week to 70% in another. In blogs, the biggest weekly differential in his negative attention was 29 percentage points. On Twitter Romney saw his negatives vacillate from as low as 23% one week to as much as 53% in another. On blogs, the biggest weekly differential was nine percentage points.

Even Paul, who enjoyed a consistently positive narrative on Twitter, saw the percentage of positive assertions range from 43% one week to 64% in another-a difference of 21 points. On blogs the biggest spread in the percentage of positive assertions from one week to another was eight points.

Perhaps nobody had a wilder ride on Twitter than Gingrich, whose negative coverage ranged from 19% one week to 70% another-a differential of 51 points. In blogs, his negatives varied much less, 25 points.

Another characteristic of the campaign discourse on Twitter was its sometimes viral nature. Some weeks, traffic about a candidate was driven by pithy (and often pointed) quips-sometimes from celebrities with large followings on Twitter-that would rapidly spread and reach enormous volume. Late night talk host Conan O’Brien generated plenty of attention when he tweeted, in an unflattering reference to Newt Gingrich’s appearance, that the former Speaker “is the #1 candidate in the ‘Could be Related to Bilbo Baggins’ category.” (Baggins was a character in J.R.R. Tolkien’s book, The Hobbit). That week, 59% of the Twitter opinions about Gingrich were negative compared with only 17% positive.

In that same vein, Perry’s reference to Social Security as a Ponzi scheme during a September 7 presidential debate generated a pun-ish response comparing the candidate’s coiffure to that of a 1970’s sitcom character: “Rick Perry’s hair is a Fonzi scheme.” That week, Perry had a tough narrative on Twitter, with negative assertions exceeding positive ones by 44 percentage points.

Pop culture references were popular in the Twitter campaign discourse, as well. After one Obama critic tweeted that he wouldn’t mind if this administration had an “it was all a dream” ending-a reference to the famous final episode of the 1980’s sitcom “Newhart”-it triggered this tweet from conservative commentator Jonah Goldberg:

“I prefer a Scooby Doo ending where Obama’s mask is torn off and he blames those meddling kids.”

One other characteristic of the social media platform is that comments were sometimes very personal and pungent and even profane in nature, using language and leveling allegations that would be off limits in more traditional news coverage and considerably less likely to show up in the blogosphere.