Discussions of the current generation of workforce automation technologies often focus on their impact on manufacturing employment and productivity. But the coming wave of advances in automation offers the potential for even greater disruption of traditional modes of work. Developments in sensors and robotics may potentially reduce the need for humans in a variety of physical applications – from taxi and truck drivers to retail store employees. Simultaneously, multipurpose artificial intelligence and machine learning technology may dramatically alter or make redundant a wide range of white collar jobs.

Scenario: A future in which machines are able to do many jobs currently performed by humans

Survey respondents were asked to read and respond to the following scenario: “New developments in robotics and computing are changing the nature of many jobs. Today, these technologies are mostly being used in certain settings to perform routine tasks that are repeated throughout the day. But in the future, robots and computers with advanced capabilities may be able to do most of the jobs that are currently done by humans today.”

A number of researchers have attempted to quantify the extent to which these new advancements might impact the future of work. A 2013 study by researchers at Oxford University estimated that nearly half (47%) of total U.S. employment is at some risk of “computerization,” while a recent report from the McKinsey Global Institute estimated that up to half of the activities people are currently paid to perform could be automated simply by adapting technologies that already have been proven to work. Meanwhile, a survey of experts in the field of artificial intelligence found that on average these experts anticipate a 50% probability that “high level machine intelligence” – that is, unaided machines that can accomplish any given task better and more cheaply than humans – will be developed within the next 45 years. On the other hand, others have argued that the risk these technologies pose to human employment is overblown and that they will not impact jobs in large numbers for many years, if ever.

The Pew Research Center survey seeks to add to this existing body of research by gauging Americans’ expectations and attitudes toward a world in which advanced robots and computer applications are competitive with human workers on a widespread scale. Specifically, respondents were asked to consider and answer questions about a scenario (highlighted in the accompanying sidebar) in which robots and computers have moved beyond performing repeated or routine tasks and are now capable of performing most of the jobs that are currently done by humans.

For the most part, Americans consider this scenario to be plausible; express more worry than enthusiasm about the prospect of machines performing many human jobs; and anticipate more negative than positive outcomes from this development. They strongly favor the notion that machines might be limited to jobs that are dangerous or unhealthy for humans, and they offer somewhat more measured support for other types of interventions to limit the impact of widespread automation, such as the enactment of a universal basic income or national service program for displaced workers. And although they view certain jobs as being more at risk than others, a significant majority of today’s workers express little concern that their own jobs or careers might be performed by machines in their lifetimes.

Broad awareness, more worry than enthusiasm about a world in which machines can perform many jobs currently done by humans

A majority of Americans are broadly familiar with the notion that automation may impact a wide range of human employment, and most consider the concept to be generally realistic. Fully 85% of the public has heard or read about this concept before, with 24% indicating they have heard or read “a lot” about it. A roughly comparable share (77%) thinks this idea is at least somewhat realistic, and one-in-five indicate that the concept seems extremely realistic to them.

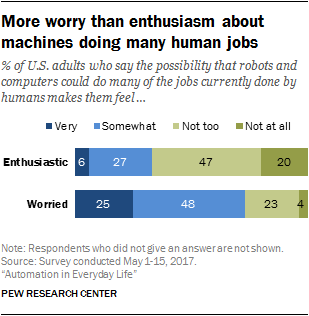

More Americans are worried than enthusiastic about the notion that machines might do many of the jobs currently done by humans. Just 33% in total are enthusiastic about this concept, and only 6% describe themselves as being very enthusiastic about it. By contrast, 72% express some level of worry about this concept – with 25% describing themselves as very worried.

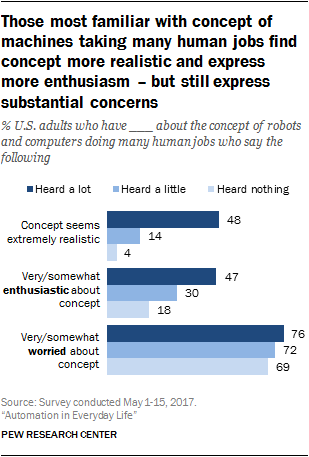

Those Americans who have heard the most about this concept find it to be much more realistic – and express substantially higher levels of enthusiasm – than do those with lower levels of awareness. Nearly half (48%) of Americans who have heard a lot about this concept find it extremely realistic that machines might one day do many of the jobs currently done by humans; that share falls to 14% among those who have heard a little about this concept and to just 4% among those who have not heard anything about it before. A similar share of these high-awareness Americans (47%) express some level of enthusiasm about the notion that machines might one day do many of the jobs currently done by humans, a figure that is also substantially higher than among those with lower levels of familiarity with this concept.

But even as those with high levels of awareness are more enthusiastic about the idea of robots and computers someday doing many human jobs, they simultaneously express just as much worry as Americans with lower levels of awareness.

Roughly three-quarters of Americans who have heard a lot about this concept (76%) express some level of worry about a future in which machines do many jobs currently done by humans. That is comparable to the share among those who have heard a little about this concept (72% of whom are worried about it) as well as those who have not heard anything about it before (69%).

Around three-quarters of Americans expect increased inequality between rich and poor if machines can do many human jobs; just one-quarter think the economy would create many new, better-paying jobs for humans

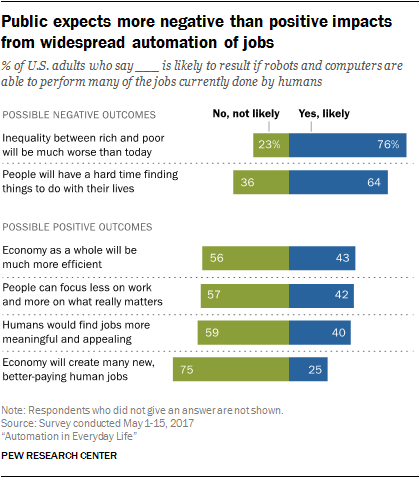

When asked about a number of possible outcomes from a world in which machines can do many of the jobs currently done by humans, the public generally expects more negative than positive outcomes. Roughly three-quarters of Americans (76%) expect that widespread automation will lead to much greater levels of economic inequality than exist today, while nearly two-thirds (64%) expect that people will have a hard time finding things to do with their lives.

Smaller shares of Americans anticipate a variety of positive outcomes from this scenario. Most prominently, just 25% of Americans expect that the economy will create many new, well-paying jobs for humans in the event that workforce automation capabilities become much more advanced than they are today; three-quarters (75%) think this is not likely to happen. Larger shares expect that this development would make the economy more efficient, let people focus on the most fulfilling aspects of their jobs, or allow them to focus less on work and more on what really matters to them in life. But in each instance, a majority of the public views these outcomes as unlikely to come to fruition.

Public is strongly supportive of limiting robots and computers to “dangerous and dirty” jobs, responds favorably to policy solutions such as a universal basic income or national service program for displaced workers

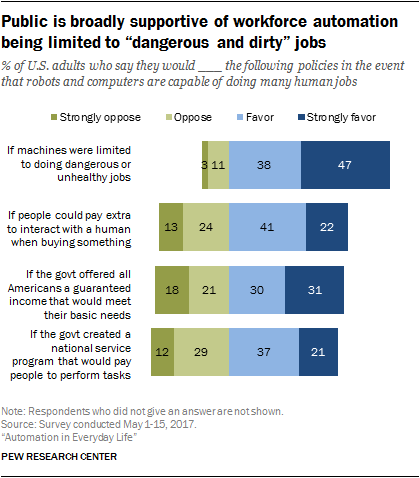

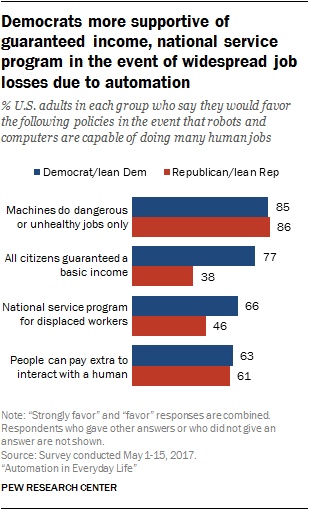

When asked about four different policies that might blunt or minimize the impact of widespread automation on human workers, the public responds especially strongly to one in particular: the idea that robots and computers be mostly limited to doing jobs that are dangerous or unhealthy for humans. Fully 85% of Americans favor this type of policy, with nearly half (47%) saying they favor it strongly.

Smaller shares of Americans – though in each instance still a majority – respond favorably to the other policies measured in the survey. These include giving people the option to pay extra to interact with a human worker instead of a machine when buying a product or service (62% of Americans are in favor of this); having the federal government provide all Americans with a guaranteed income that would allow them to meet their basic needs (60% in favor); and creating a government-run national service program that would pay people to perform tasks even if machines could do those jobs faster or cheaper (58% in favor).

Further, opposition to government job- and income-supporting programs is stronger than opposition to the idea that robots should mostly be limited to doing dangerous or unhealthy jobs. For instance, 18% of Americans are strongly opposed to a guaranteed minimum income in the event that machines take substantial numbers of jobs from humans, six times the share (3%) that is strongly opposed to limiting machines to doing only dangerous or unhealthy jobs.

The most prominent differences in Americans’ views of these concepts relate to political affiliation. Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are much more supportive than Republicans and Republican-leaning independents of both a universal basic income (77% of Democrats favor this idea, compared with just 38% of Republicans) as well as a national service program (66% vs. 46%) in the event that machines replace a large share of human jobs. On the other hand, there are no major partisan differences in support for limiting machines to dangerous and dirty jobs, or for giving people the option to pay extra to interact with a human rather than a robot in commercial transactions.

There is also some variation on this question based on educational attainment, especially in the case of a national service program that would pay displaced humans to perform jobs. Some 69% of Americans with high school diplomas or less – and 58% of those who have attended but not graduated from college – support this type of policy. But that share falls to 45% among those with four-year college degrees. Workers with lower levels of education are also more likely to favor a universal basic income in the event that machines take many human jobs, although by a smaller margin: This policy is favored by 65% of Americans with high school diplomas or less and 62% of those with some college experience, compared with 52% of those with four-year degrees or more.

The public is evenly divided on whether government or individuals should be responsible for providing for displaced workers, but is more supportive of limits on how many human jobs businesses can replace with machines

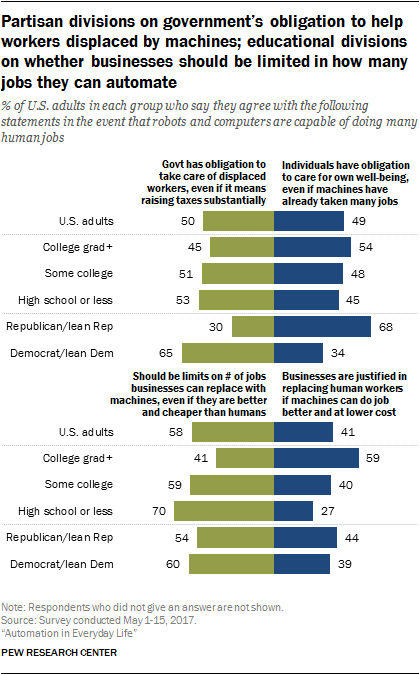

When asked whether the government or individuals themselves are most responsible for taking care of people whose jobs are displaced by robots or computers, the public is evenly split. Exactly half feel that the government would have an obligation to care for those displaced workers, even if that required raising taxes substantially. Meanwhile, a nearly identical share (49%) feels that individuals would have an obligation to care for their own financial well-beings, even if machines had already taken many of the jobs they might otherwise be qualified for.

Americans are somewhat less divided on a question about whether or not there should be limits placed on how many jobs businesses can automate. Nearly six-in-ten Americans (58%) feel there should indeed be limits on how many jobs businesses can replace with machines, while 41% take the view that businesses are justified in replacing humans with machines if they can receive better work at lower cost.

Attitudes towards the government’s obligation to take care of workers who are displaced by automation vary strongly by partisan affiliation. Some 65% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents feel that the government would have an obligation to take care of workers who are displaced by automation, even if that means higher taxes for others. Meanwhile, a nearly identical share of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (68%) feel that individuals should be responsible for their own financial well-beings even if jobs are automated on a wide scale.

But despite these pronounced differences toward this aspect of the workforce automation debate, partisan opinions are much more aligned on the question of whether or not businesses should be limited in the number of human jobs they can replace with machines. Just over half of Republicans (54%) feel that there should be limits to how many human jobs businesses can replace with machines, only slightly less than the 60% of Democrats who hold this view.

Educational differences follow the opposite pattern on this question. Americans with varying levels of educational attainment respond in broadly comparable ways on the question of whether the government has an obligation to take care of workers who have been displaced by widespread automation of jobs. But those with lower levels of educational attainment are far more supportive of limiting the number of jobs that businesses can replace with machines. Among those with high school diplomas or less, fully 70% say there should be limits on the number of human jobs that businesses can automate. That share falls to 41% among those with four-year college degrees.

Public sees different jobs as having varying degrees of automation risk – but most view their own jobs or professions as relatively safe

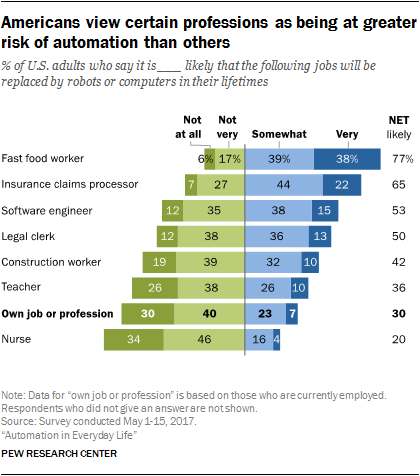

Regardless of whether major or minor impacts are expected on human employment as a whole, most studies of workforce automation anticipate that certain types or categories of jobs will be more vulnerable to this trend than others. In an effort to examine the views and expectations of the public on this question, the survey presented respondents with seven different occupations and asked them to estimate how likely they think it is that each will be mostly replaced with robots or computers during their lifetimes. These jobs include a mixture of physical and mental or cognitive work, as well as a mixture of routine and non-routine tasks. The findings indicate that Americans view some occupations as being more insulated from automation than others – but that few of today’s workers consider their own jobs or professions to be vulnerable to this trend to any significant degree.

In terms of the specific jobs evaluated in the survey, a sizable majority of Americans think it likely that jobs such as fast food workers (77%) or insurance claims processors (65%) will be done by machines during their lifetimes. The public is more evenly split on whether or not software engineers and legal clerks will follow suit, while other jobs are viewed as more insulated from being replaced by machines. Nursing is the most prominent of these: Just 4% of Americans think it very likely that nurses will be replaced by robots or computers over the span of their lifetimes, while 34% think this outcome is not at all likely.

In a previous Pew Research Center survey on workforce automation, workers have expressed a high level of confidence that their own jobs or professions will be performed by humans for the foreseeable future – and this survey finds continuing evidence of this long-standing trend. Just 30% of workers think it likely that their own jobs or professions will be replaced by robots or computers during their lifetimes, and only 7% describe this scenario as very likely. Put differently, Americans view their own jobs or professions” as the second-most safe job from the perspective of automation risk: only nursing is viewed as a safer option.

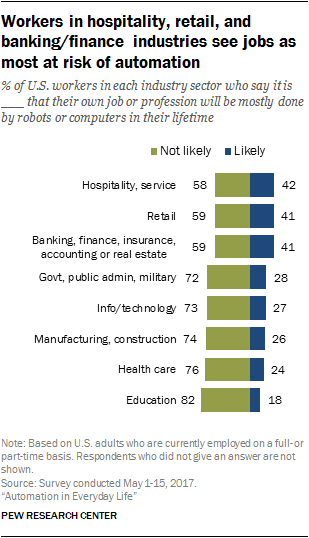

Majorities of workers across various industry sectors feel it is not likely that their jobs will be automated over the course of their own lifetimes, but workers in certain industries feel that their jobs are more at risk than in others. Specifically, roughly two-in-five workers who work in hospitality and service (42%), retail (41%), or banking, finance, insurance, accounting or real estate (41%) feel that their job is at least somewhat at risk of being automated in the future. Meanwhile, relatively few workers in the education sector consider their jobs to be at risk of automation: just 18% of these workers consider it likely that their jobs will be done by machines in their lifetimes.

By the same token, workers with high levels of educational attainment are more likely to feel that their jobs are safe from automation relative to workers with lower education levels. Just 22% of workers with at least four-year college degrees expect that their jobs will eventually be done by robots or computers, compared with 33% of those with some college experience and 36% of those with high school diplomas or less.

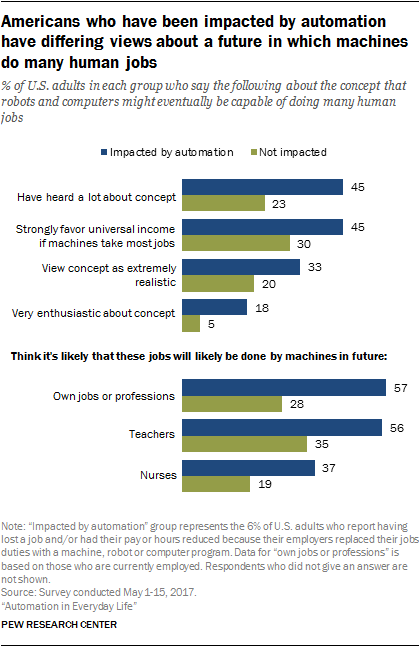

Americans who have been personally impacted by workforce automation have unique attitudes toward a future in which machines do many human jobs

The 6% of Americans who have already been impacted by automation in their own careers (and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 1 of this report) respond to this concept in ways that are notably different from the rest of the population. Compared with other Americans, this group is around twice as likely to have heard a lot about this concept and is also more likely to find it extremely realistic that machines might one day perform many human jobs. They see greater automation risk to jobs that other Americans consider to be relatively safe (such as teachers and nurses) and express greater support for a universal basic income in the event of widespread automation of jobs.

They are also one of the few groups who think it is more likely than not that their own jobs or professions will likely be done by computers or robots within their lifetimes: 57% of these workers think it’s very or somewhat likely that this will be the case, compared with 28% of employed adults who have not been personally impacted by automation in their own jobs.

Yet even as they see greater risks to human employment, the views of this group are far from universally negative. They are around three times as likely as other Americans to describe themselves as very enthusiastic about this concept. And larger shares think it’s likely that the economy will become more efficient as a result of widespread automation of jobs (55% vs. 42%) or that many new, well-paying jobs for humans will result from this development (37% vs. 24%).

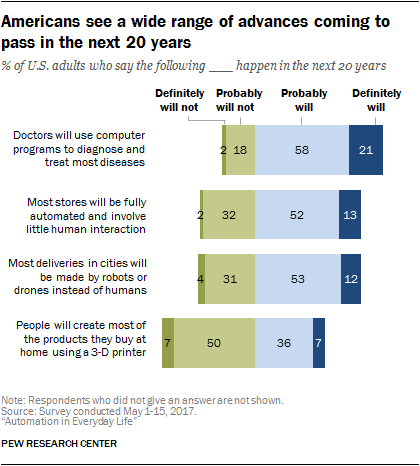

The public views other types of automation as likely within the coming decades

Roughly eight-in-ten Americans (79%) think it’s likely that within 20 years doctors will use computer programs to diagnose and treat most diseases, with 21% expecting that this will definitely happen. Smaller majorities of Americans expect that most stores will be fully automated and involve little interaction between customers and employees, or that most deliveries in major cities will be made by robots or drones rather than humans (65% in each case). Conversely, fewer Americans (43%) anticipate that people will buy most common products simply by creating them at home using a 3-D printer.