When people consider engaging with facts and information any number of factors come into play. How interested are they in the subject? How much do they trust the sources of information that relate to the subject? How eager are they to learn something more? What other aspects of their lives might be competing for their attention and their ability to pursue information? How much access do they have to the information in the first place?

A new Pew Research Center survey explores these five broad dimensions of people’s engagement with information and finds that a couple of elements particularly stand out when it comes to their enthusiasm: their level of trust in information sources and their interest in learning, particularly about digital skills. It turns out there are times when these factors align – that is, when people trust information sources and they are eager to learn, or when they distrust sources and have less interest in learning. There are other times when these factors push in opposite directions: people are leery of information sources but enthusiastic about learning.

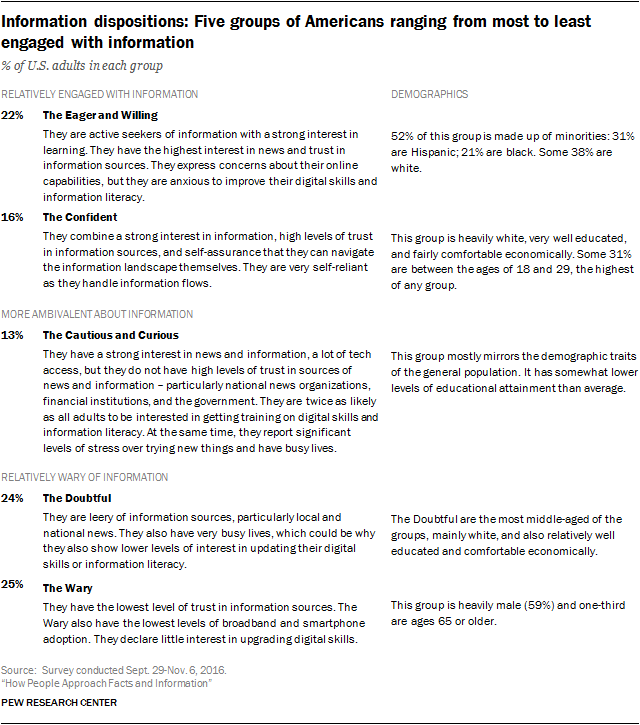

Combining people’s views toward new information – and their appetites for it – allows us to create an “information-engagement typology” that highlights the differing ways that Americans deal with these cross pressures. The typology has five groups that fall along a spectrum ranging from fairly high engagement with information to wariness of it. Roughly four-in-ten adults (38%) are in groups that have relatively strong interest and trust in information sources and learning. About half (49%) fall into groups that are relatively disengaged and not very enthusiastic about information or about gaining more training, especially when it comes to navigating digital information. Another 13% occupy a middle space: They are not particularly trusting of information sources, but they show higher interest in learning than those in the more information-wary groups.

Here are the groups:

The Eager and Willing – 22% of U.S. adults

At one end of the information-engagement spectrum is a group we call the Eager and Willing. Compared with all the other groups on this spectrum, they exhibit the highest levels of interest in news and trust in key information sources, as well as strong interest in learning when it comes to their own digital skills and literacy. They are not necessarily confident of their digital abilities, but they are anxious to learn. One striking thing about this group is its demographic profile: More than half the members of this group are minorities: 31% are Hispanic; 21% are black and 38% are white, while the remainder are in other racial and ethnic groups.

The Confident – 16% of adults

Alongside the Eager and Willing are the Confident, who are made up of the one-in-six Americans and combine a strong interest in information, high levels of trust in information sources, and self-assurance that they can navigate the information landscape on their own. Few feel they need to update their digital skills and they are very self-reliant as they handle information flows. This group is disproportionately white, quite well educated and fairly comfortable economically. And one-third of the Confident (31%) are between the ages of 18 and 29, the highest share in this age range of any group.

The Cautious and Curious – 13% of adults

The Cautious and Curious have a strong interest in news and information, even though they do not have high levels of trust in the sources of news and information – particularly national news organizations, financial institutions and the government. But they are interested in growth, with a great deal of interest in improving digital skills and literacy. This group differs very little from the general population’s average, although its members have somewhat lower levels of educational attainment than the mean.

The Doubtful – 24% of adults

The Doubtful are less interested in news and information than those in the previous groups. They are leery of news and information sources, particularly local and national news. They also have very busy lives, which could be why they also show little interest in updating their digital skills or information literacy. The Doubtful are the most middle-aged of the groups. They tilt towards being white and they are also relatively well-educated and above average in their economic status.

The Wary – 25% of adults

At the edge of the spectrum are the Wary. They are the least engaged with information. They have very low interest in news and information, low trust in sources of news and information and little interest in acquiring information skills or literacies. That places them at a distance from other Americans in terms of engagement with information. This group is heavily male (59%) and one-third are ages 65 or older.

What are the implications of the typology, especially for issues tied to digital divides and information literacy?

Typologies are useful because they add to the insights that can be gained by doing traditional analysis by demographics – such as gender, race, class, age and educational attainment.

One key takeaway from these typology findings is that there is not a “typical,” archetypal information consumer. A variety of factors shape people’s engagement with information. There is clear variation among citizens about their interest in information, trust in various sources and their eagerness to gain further skills dealing with information.

This typology suggests that one size does not fit all when it comes to information outreach. For instance, information purveyors might need to use very different methods to get material to the Eager and Willing, who are relatively trusting of institutional information and eager to learn, compared with the tactics they might consider in trying to get the attention of the Cautious and Curious, who are open to learning but relatively distrusting of institutional information. Similarly, groups with messages might want to plan wholly different processes to reach the Confident (who are basically information omnivores), compared with the Wary (who are quite reluctant to engage with new material).

Secondly, the typology highlights the challenges faced by those focusing on digital divides and information literacy as they try to help people improve their access to information and find trustworthy material. On the one hand, significant numbers of people are interested in building digital skills and information literacy. On the other hand, about half of adults fall into the groups we call the Doubtful and the Wary, who have lower interest in getting assistance to help them get to more trustworthy material.

And a third takeaway from the typology highlights how useful it would be if there were trusted institutions helping people gain confidence in their digital- and information-literacy skills. Libraries might be relevant here. Library users stand out in their information engagement. Overall, about half (52%) of adults have visited a public library or connected with it online in the past year. Those library users are overrepresented in the two most information-engaged groups. Some 63% of the Eager and Willing were library users in the past year, while this is true for 58% of the Confident. Additionally, both groups are much more likely than others to say they trust librarians and libraries as information sources.

At the same time, some words of caution are warranted. First, as broad as they were, the questions in this survey did not cover the vast range of people’s connection to information and use of it. Nor did they comprehensively probe people’s attitudes about learning and personal growth. The poll covered particular contexts and it focused on digital access to information. Thus, the results are not projectable to all aspects of people’s vast experiences with media and information.

Another caution: While there are numerical descriptions of the groups, there is some fluidity in the boundaries of the groups. Unlike many other statistical techniques, cluster analysis does not require a single “correct” result. Instead, researchers run numerous versions of it (e.g., asking it to produce different numbers of clusters) and judge each result by how analytically practical and substantively meaningful it is. Fortunately, nearly every version produced had a great deal in common with the others, giving us confidence that the pattern of divisions was genuine and that the comparative shares of those who are relatively engaged and relatively wary of information are generally accurate.

A third caution is that the findings represent a snapshot of where adults are today in a changing information ecosystem. The groupings reported here may well change in the coming years as people’s comfort and confidence with accessing information digitally evolve and as technologists offer new ways for people to encounter and create information.

Even allowing for those caveats, these findings add insight to swirling debates about how people think about and use information.