For many years concerns about “digital divides” centered primarily on whether people had access to digital technologies. Now, those worried about these issues also focus on the degree to which people succeed or struggle when they use technology to try to navigate their environments, solve problems, and make decisions. A recent Pew Research Center report showed that adoption of technology for adult learning in both personal and job-related activities varies by people’s socio-economic status, their race and ethnicity, and their level of access to home broadband and smartphones. Another report showed that some users are unable to make the internet and mobile devices function adequately for key activities such as looking for jobs.

In this report, we use newly released Pew Research Center survey findings to address a related issue: digital readiness. The new analysis explores the attitudes and behaviors that underpin people’s preparedness and comfort in using digital tools for learning as we measured it in a survey about people’s activities for personal learning.

Specifically, we assess American adults according to five main factors: their confidence in using computers, their facility with getting new technology to work, their use of digital tools for learning, their ability to determine the trustworthiness of online information, and their familiarity with contemporary “education tech” terms. It is important to note that the findings here just cover people’s learning activities in digital spaces and do not address the full range of important things that people can do online or their “readiness” to perform them.

To better understand the way in which different groups of Americans line up when it comes to digital readiness, researchers used a statistical technique called cluster analysis that places people into groups based on similarities in their answers to key questions.

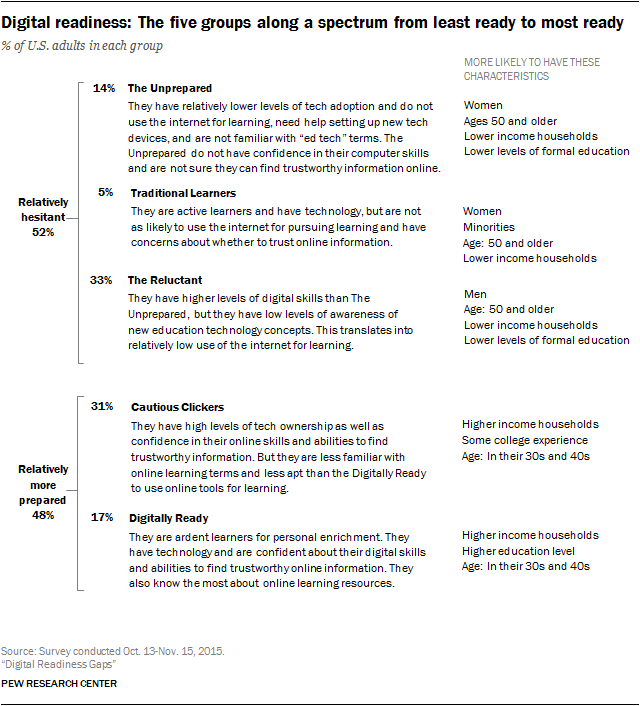

The analysis shows there are several distinct groups of Americans who fall along a spectrum of digital readiness from relatively more prepared to relatively hesitant. Those who tend to be hesitant about embracing technology in learning are below average on the measures of readiness, such as needing help with new electronic gadgets or having difficulty determining whether online information is trustworthy. Those whose profiles indicate a higher level of preparedness for using tech in learning are collectively above average on measures of digital readiness.

Relatively Hesitant – 52% of adults in three distinct groups. This overall cohort is made up of three different clusters of people who are less likely to use digital tools in their learning. This has to do, in part, with the fact that these groups have generally lower levels of involvement with personal learning activities. It is also tied to their professed lower level of digital skills and trust in the online environment.

- A group of 14% of adults make up The Unprepared. This group has both low levels of digital skills and limited trust in online information. The Unprepared rank at the bottom of those who use the internet to pursue learning, and they are the least digitally ready of all the groups.

- We call one small group Traditional Learners, and they make up of 5% of Americans. They are active learners, but use traditional means to pursue their interests. They are less likely to fully engage with digital tools, because they have concerns about the trustworthiness of online information.

- A larger group, The Reluctant, make up 33% of all adults. They have higher levels of digital skills than The Unprepared, but very low levels of awareness of new “education tech” concepts and relatively lower levels of performing personal learning activities of any kind. This is correlated with their general lack of use of the internet in learning.

Relatively more prepared – 48% of adults in two distinct groups. This cohort is made up of two groups who are above average in their likeliness to use online tools for learning.

- A group we call Cautious Clickers comprises 31% of adults. They have tech resources at their disposal, trust and confidence in using the internet, and the educational underpinnings to put digital resources to use for their learning pursuits. But they have not waded into e-learning to the extent the Digitally Ready have and are not as likely to have used the internet for some or all of their learning.

- Finally, there are the Digitally Ready. They make up 17% of adults, and they are active learners and confident in their ability to use digital tools to pursue learning. They are aware of the latest “ed tech” tools and are, relative to others, more likely to use them in the course of their personal learning. The Digitally Ready, in other words, have high demand for learning and use a range of tools to pursue it – including, to an extent significantly greater than the rest of the population, digital outlets such as online courses or extensive online research.

There are several important qualifying notes to sound about this analysis. First, the research focuses on a particular activity – online learning. The findings are not necessarily projectable to people’s capacity (or lack of capacity) to perform health-related web searches, use mobile apps for civic activities, or use smartphones to apply for a job.

Second, while there are numerical descriptions of the groups, there is some fluidity in the boundaries of the groups. Unlike many other statistical techniques, cluster analysis does not require a single “correct” result. Instead, researchers run numerous versions of it (e.g., asking it to produce different numbers of clusters) and judge each result by how analytically practical and substantively meaningful it is. Fortunately, nearly every version produced had a great deal in common with the others, giving us confidence that the pattern of divisions were genuine and that the comparative shares of those who were relatively ready and not ready each constituted about half of Americans.

Third, it is important to note that the findings represent a snapshot of where adults are today in a fairly nascent stage of e-learning in society. The groupings reported here may well change in the coming years as people’s understanding of e-tools grows and as the creators of technology related to e-learning evolve it and attempt to make it more user friendly.

Even allowing for those caveats, the findings add additional context to insights about those who pursue personal learning activities. Although factors such as educational attainment or age might influence whether people use digital tools in learning, other things such as people’s digital skills and their trust in online information may also loom large. These “readiness” factors, separate and apart from demographic ones, are the focus in this report.

The results are also significant in light of Americans’ expressed interest in learning and personal growth. Most Americans said in the Center survey that they like to look for opportunities to grow as people: 58% said this applies to them “very well” and another 31% said it applies to them “somewhat well.” Additionally, as they age, many Americans say they hope to stay active and engaged with the world.