Teens take steps to shape their reputation, manage their networks, and mask information they don’t want others to know.

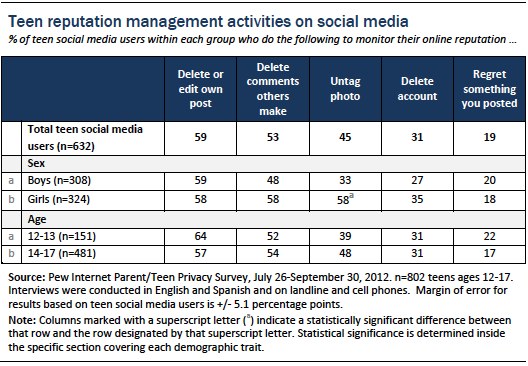

Teens are cognizant of their online reputations and take steps to curate the content and appearance of their social media presence. Teens’ management of their profiles can take a variety of forms—we asked teen social media users about five specific activities that relate to the content they post and found that:

- 59% have deleted or edited something that they posted in the past

- 53% have deleted comments from others on their profile or account

- 45% have removed their name from photos that have been tagged to identify them

- 31% have deleted or deactivated an entire profile or account

- 19% have posted updates, comments, photos, or videos that they later regretted sharing

Overall, there are relatively few demographic differences between groups around these kinds of reputation management behaviors—older and younger teens are for the most part equally likely to prune or edit their profiles in these ways, as are boys and girls (with some modest exceptions as will be discussed in more detail below).

Among teen social media users, nearly six in ten teens (59%) have deleted or edited something that they posted to their profile in the past. Children of college-educated parents are more likely to have cleaned up something posted in the past than youth whose parents have a high school diploma (66% vs. 51%).

About half of teen social media users (53%) have deleted comments that others have made on their profile or account. Older girls ages 14 to 17 are more likely to delete comments on their profile than boys of the same age. Six in ten (60%) older girls have deleted comments on their profiles, while 48% of boys ages 14 to 17 have done the same. Teens with Twitter accounts are more likely than non-Twitter users to delete comments (63% vs. 50%).43

Just under half (45%) of teen social media users have removed their name from photos that have been tagged to identify them. Girls are more likely than boys to untag themselves from photos posted on social media, with 58% of girls reporting engaging in this behavior compared with a third (33%) of boys. Teens with Twitter accounts are more likely than non-Twitter users to untag photos (59% vs. 41%).

About one in three (31%) teen social media users have deactivated or deleted a social media profile or account. African-American teens who are social media users are more likely to report deactivating or deleting a profile; 44% of African-American social media users have deactivated or deleted a social media profile, compared with 26% of white teens.44 Lower income teens from families earning less than $50,000 a year are more likely to have deactivated or deleted an account or profile than teens from wealthier households; 37% of lower income teens have deleted an account, compared with 26% of those living in households earning $50,000 or more per year. Urban youth are also more likely to have deleted a profile when compared with suburban teens; 38% of urban teens have deactivated or deleted a profile or account, compared with 27% of suburban youth. There are no differences in deletion or deactivation of a profile between boys and girls. However, teens with Twitter accounts are more likely than non-Twitter users to say they have deactivated or deleted a social media account (41% vs. 27%).

One in five teen social media users (19%) say they have posted an update, comment, photo or video to a social media site that they later regretted sharing. Younger boys are more likely to report regretting content they posted than older boys (30% vs. 16%).

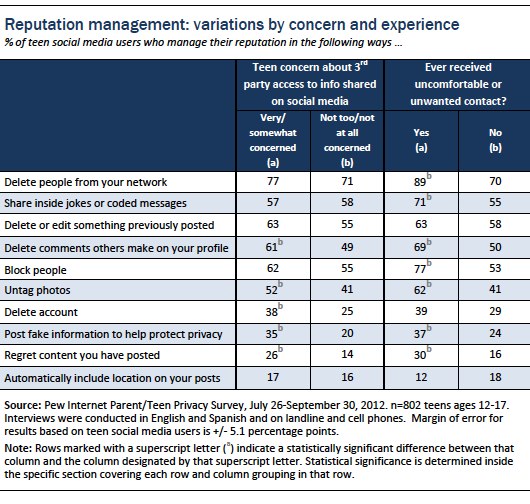

Teens who are concerned about third party access to their personal information are also more likely to engage in online reputation management.

Teens who are “somewhat” or “very” concerned that some of the information they share on social media sites might be accessed by third parties like advertisers or businesses without their knowledge are more likely to engage in various reputation management activities when compared with teens who do not share these concerns. Some 61% have deleted comments, while 49% of less concerned teens have done so. Similarly, 52% of teens who are very or somewhat concerned about third parties accessing their data without their knowledge have untagged themselves in photos, while 41% of less concerned teens say the same. And 38% of concerned teens have deleted or deactivated a profile or account, compared with 25% of less concerned or unconcerned teens. Teens worried about third party access to their personal information are also more likely than less concerned teens (26% vs. 14%) to say they have regretted something that they shared in the past on social media.

Teens who have been contacted online by someone they did not know in a way that made them feel scared or uncomfortable are substantially more likely to engage in many reputation managing behaviors on social media.

As will be discussed further in Part 4 of this report, 17% online teens say they have been contacted online by someone they did not know in a way that made them feel scared or uncomfortable. Teens who have experienced unwanted or uncomfortable contact are more likely to delete comments on their profile (69% vs. 50%), to untag themselves from photos (62% vs. 41%) and to say that they have posted photos or content that they later regretted sharing (30% vs. 16%).

Friend management and network curation

Network curation is also an important part of privacy and reputation management for social media-using teens

As noted above, most teens do not have public Facebook profiles. However, they typically maintain large networks of friends on sites like Facebook, and few take steps to limit what certain friends and parents can see. The practice of friending, unfriending, and blocking serve as yet another set of essential privacy management techniques for controlling who sees what and when.

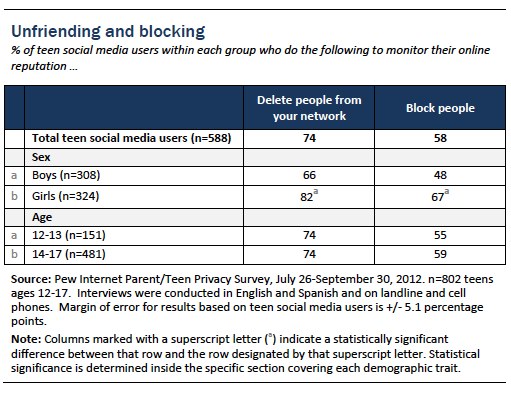

Three in four (74%) teen social media users have deleted people from their network or friends’ list. Network pruning is most common among girls; 82% of teen girls who are social media users delete friends from their network, compared with 66% of boys who do so. Unfriending is equally common among teens of all ages and socioeconomic groups.

In addition, nearly six in ten teen social media users (58%) have blocked people on these sites. Teen girls are once again more likely than boys who are social media users to say that they have blocked someone on the sites they use (67% vs. 48%). Teens of all ages and socioeconomic groups are equally likely to say that they block other people on social media sites. However, teens who use Twitter are more likely to report blocking, when compared with non-Twitter users (73% vs. 53%).

Teen social media users who have experienced unwanted or uncomfortable contact are also more likely than those who have not to report unfriending (89% vs. 70%) and blocking people (77% vs. 53%).

Other privacy protecting and obscuring behaviors

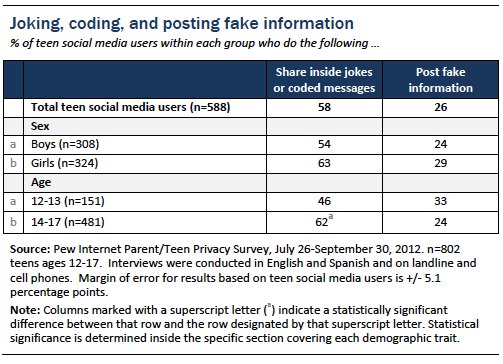

Many teen social media users will make the content they share more private by obscuring some of their updates and posts, sharing inside jokes and other coded messages that only certain friends will understand; 58% of teen social media users say they share inside jokes or cloak their messages in some way.45 Older teens are considerably more likely than younger teens to say that they share inside jokes and coded messages that only some of their friends understand (62% vs. 46%). Girls and boys are equally likely to post inside jokes and coded messages, as are teens across all socioeconomic groups.

In addition, one in four (26%) teen social media users say that they post fake information—such as a fake name, age or location—to help protect their privacy. Boys and girls and teens of all ages are equally likely to do this. However, African-American teens who use social media are more likely than white teens to say that they post fake information to their profiles (39% vs. 21%).

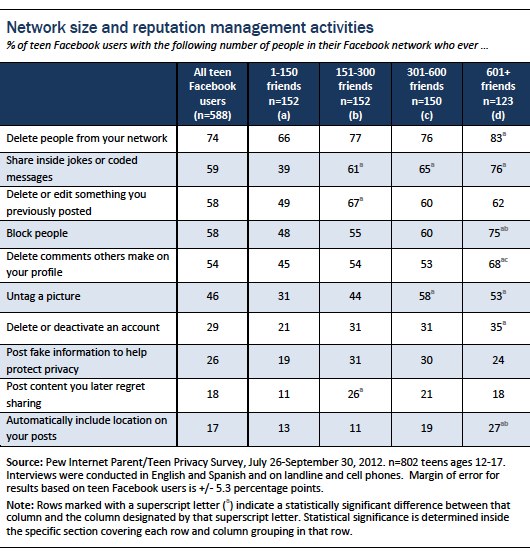

Teens with large friend networks are more active reputation managers on social media.

Teens with larger friend networks also tend to be more active when it comes to managing and maintaining their online personas.46 They are more likely than those with smaller networks to block other users, to delete people from their friend network entirely, to untag photos of themselves, and to delete comments others have made on their profile. They are also substantially more likely to automatically include their location in updates and share inside jokes or coded messages with others.

Interestingly, some of these reputation management activities exhibit spikes at different points in the network size spectrum. For example, blocking people, deleting comments, and automatically including one’s location sees a dramatic increase at around 600 Facebook friends. The act of sharing inside jokes or coded messages becomes more common among those with more than 150 friends, and untagging photos follows a similar pattern.

More than half of internet-using teens have decided not to post content online over reputation concerns.

Social media platforms are by no means the sole site of personal information sharing online, and there are many places where teens make daily decisions about what to share and who to share it with. Many teens have decided not to post something online out of concern that it will reflect poorly on them later. More than half of online teens (57%) say they have decided not to post something online because they were concerned it would reflect badly on them in the future.47 Teen social media users are more likely than other online teens who do not use social media to say they have refrained from sharing content due to the future impact it might have on their reputation (61% vs. 39%).

The oldest youth—online teens ages 16 and 17—are more likely than younger teens to say that they’ve decided not to post content online over concerns about how it will reflect on them; 67% of online teens ages 16-17 say they have withheld content, compared with 52% of 14-15 year-olds. In addition, white and African-American youth are more likely to decide not to post something over reputational concerns when compared with Hispanic youth.48 Just about two thirds of white and African-American youth (61% and 63% respectively) say they have decided not to share some content online, while 45% of Hispanic youth say the same.

Rural youth are more likely (67%) than urban youth (51%) to say that they have refrained from posting something over reputational concerns.

[five]

Some teens find themselves in the role of policing or advising their friends when they post sensitive or personal information online. One high school boy describes one such situation: “I had a friend that was always putting his personal info on Facebook, and I told him that certain info shouldn’t be shared with everyone.”

[and]

In our in-person focus groups, the influence of adults was also discussed:

How Adults Influence Teens’ Social Media Behavior

Much of teen social media behavior is driven by the ways in which they socialize with peers online. However, teens have a sense of the watchful and potentially judgmental eye of adults, and this is a key influencer of the choices they make online. There is a common attitude among focus group participants that as soon as something is posted online, there is a risk that it is no longer private.

[adult scrutiny]

Some focus group participants discussed the importance of creating a good presentation of themselves online in order to maintain positive in-person relationships with adults.

Male (age 18): “Yeah, I have some teachers who have connections that you might want to use in the future, so I feel like you always have an image to uphold. Whether I’m a person that likes to have fun and go crazy and go all out, but I don’t let people see that side of me because maybe it changes the judgment on me. So you post what you want people to think of you, basically.”

Most focus group participants are keenly aware that their online content is visible to the adults in their lives. This visibility raises multiple concerns. Certainly, many teens fear negative judgments and sometimes repercussions from adults in positions of authority.

[School Resource Officer]

Other worries for teens stem from adults seeing a different side of them than what they project, which teens feel adults would take out of context and not be able to be able to appropriately interpret. Thus, many focus group participants employ a variety of strategies to regulate their content, knowing that adults may be watching.

[s]

The pressures of college admission and employment, in particular, seem to have a big influence on online behavior.

[college admissions officers]

Others actively hide things, or employ complicated strategies for selectively displaying content – especially maintaining multiple accounts.

Female (age 15): “Yeah, I just hide things from my parents.” Female (age 15): “I have two accounts. One for my family, one for my friends…But it’s not like I have anything to hide, it’s just they’re so nosy and they judge everything I do.”

The vast majority of teen Facebook users say that their parents and other adults see the same content and updates that all of their friends see, suggesting that having multiple Facebook accounts is not a common practice. Still, focus groups show that in many cases, the effect of adults policing their teens’ social media use is indeed that teens are inspired to go to great lengths to maintain their reputation. Teens have a ‘reputation’ with their parents just as much as with the outside world, and they are careful to protect it because losing this reputation can have immediate negative consequences (whether mere embarrassment or getting in trouble).

The net effect of teens protecting the reputations they have with adults may still protect teens’ overall reputation: if a teen’s tactics are successful at not raising objections from his or her parents, the tactics may well also be effective at preventing other potentially judgmental adults from seeing parts of the teen’s private life and discriminating against him or her based on it.