Teens have become more likely to share certain kinds of information on social media sites.

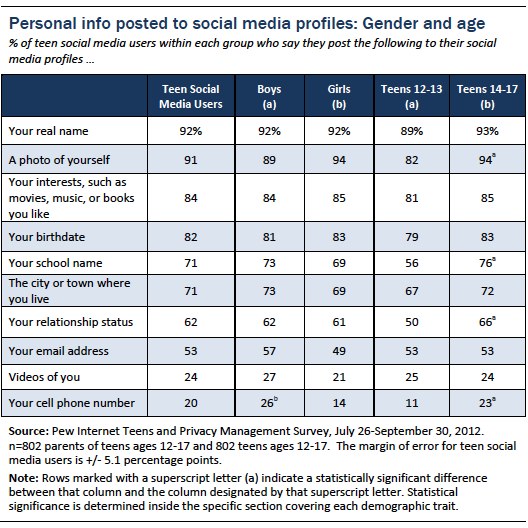

Teens share a wide range of information about themselves on social media sites; indeed the sites themselves are designed to encourage the sharing of information and the expansion of networks. However, few teens embrace a fully public approach to social media. In our 2012 survey, we asked about ten different categories of personal information that teen social media users might post on the profile they use most often and found that:

- 92% post their real name

- 91% post a photo of themselves

- 84% post their interests, such as movies, music, or books they like

- 82% post their birth date

- 71% post their school name

- 71% post the city or town where they live

- 62% post their relationship status

- 53% post their email address

- 24% post videos of themselves

- 20% post their cell phone number

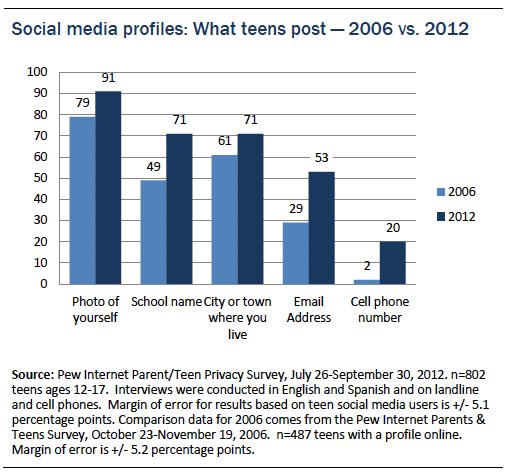

Since 2006, the act of sharing certain kinds of personal information on social media profiles19 has become much more common. For the five different types of personal information that we measured in both 2006 and 201220, each was significantly more likely to be shared by teen social media users in our most recent survey.

Generally speaking, older teens (those 14-17), are more likely to share certain types of information online than younger teens, ages 12-13. Older teens more frequently share a photo of themselves, their school name, their relationship status, and their cell phone number. While boys and girls generally share personal information on social media profiles at the same rates, cell phone numbers are the sole exception. Boys are significantly more likely to share their cell phone numbers than girls, a difference that is driven by older boys. Various differences between white and African-American social media-using teens are also significant, with the most notable being the lesser tendency for African-American teens to disclose their real names on a social media profile.21

Many factors could be influencing this increase in information sharing among teens. Shifts from one platform to another (e.g. MySpace to Facebook), dramatic changes in the devices teens use to connect to their networks, as well as near-constant changes to the interfaces teens engage with have all undoubtedly had some influence on the likelihood that teens will post certain kinds of information to their profile. The technological landscape has changed radically over the last six years, and many of these information sharing practices map to the evolution of the platforms that teens use. Certain pieces of information are required at signup while others are actively solicited through the interface design. At the same time, the adults in teens’ lives have also become much more likely to be social media users, further normalizing many of these sharing behaviors.

What follows next is a more detailed analysis of who shares what information on social networking sites.

Most teens use their real name on the profile they use most often.

More than nine-in-ten (92%) teens who use social networking sites or Twitter share their real name on the profile they use most often.22 Given that Facebook is now the dominant platform for teens, and a first and last name is required when creating an account, this is undoubtedly driving the nearly universal trend among teen social media users to say they post their real name to the profile they use most often. Fake accounts with fake names can still be created on Facebook, but the practice is explicitly forbidden in Facebook’s Terms of Service.23 However, Twitter and some other social network sites have no such restrictions.

Regardless of age or gender, teen social media users are equally likely to say that they post their real name to their profile. However, white teens who are social media users are more likely than African-American teens to say that they post their real name to their profile (95% vs. 77%).24

Nearly all teens post photos of themselves to their online profile, a feature that is integral to the design and functioning of the most popular social network sites.

Among teen social media users, 91% say that they have posted a photo of themselves on the profile or account they use most often, up from 79% in 2006. Photo sharing is a central function of social media engagement and expression for teens. As increasing numbers of teens acquire internet-connected smartphones with high-resolution cameras, the act of sharing photos has become a seamless part of shaping one’s online identity and sharing one’s offline experiences with friends.25

Older teens ages 14-17 are more likely than younger teens ages 12-13 to say that they include a photo of themselves on their profile (94% vs. 82%). Girls and boys are equally likely to include a photo of themselves, and there are no significant variations by race or ethnicity.

The sharing of interests is fundamental to social media participation and as such, more than eight in ten (84%) teen social media users share their personal interests on their profile, such as movies, music or books they like.26 There are no differences by age, gender, race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status for this question.

Another piece of information that is often required at signup is a teen’s birth date. Eight in ten (82%) teen social media users posted their birthdate to the profile or account they use most often.27 There are no differences by age, gender, race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status for this question.

Seven in ten (71%) social media-using teens say they have posted their school name to the profile they use most often, compared with just 49% who reported doing so in 2006. Older teens are more likely than younger teens to publish their school name on their profile (76% vs. 56%), which is the only significant demographic variation for this behavior.

Similarly, 71% of social media-using teens say they post the city or town where they live to their profile, up from 61% in 2006. One’s location is another basic piece of information that is asked of a user during the process of signing up for an account on Facebook.

The lack of variation by gender, age, or any other key demographic variables for many of these activities suggests a pattern of disclosure that maps to the design of the interface and the sites’ policies which teens encounter when creating their accounts.

Sharing a relationship status is slightly less common, although it is still posted by a majority of social networking teens. Six-in-ten (62%) share a relationship status.28 Older teen social media users are more likely than younger teens to disclose their relationship status (66% vs. 50%), but girls and boys do so at the same rate. White teen social media users are more likely than African-American teens to share their relationship status (65% vs. 44%).29

The practice of posting an email address has also become more common; 53% of teen social media users now report posting that information to their profile, while just 29% reported doing so in 2006. Teen social media users are equally likely to say that they post their email address to their profile, regardless of age or gender.

One in four social media-using teens (24%) post videos of themselves to the profile they use most often. Teens whose parents have higher levels of education and income are somewhat more likely than teens whose parents have lower levels of educational attainment or annual incomes to say they share videos of themselves on the social media profile they use most often—a finding that may be influenced by the tech assets of the family. However, there are no significant variations according to the age or gender of the teen.

Cell phone numbers, which were very rarely included on teen profiles in 2006 (only 2% of teens posted them at that time), are now shared by 20% of teen social media users. This increase is likely influenced by a concurrent rise in cell phone ownership among teens. Older teens, who have higher cell phone ownership when compared with younger teens, are also more likely to post their cell number to their social media profile (23% vs. 11%).

While boys and girls generally share personal information on social media profiles at the same rates, cell phone numbers are the sole exception. Boys are significantly more likely to share their numbers than girls (26% vs. 14%). This difference is driven entirely by older boys; 32% of boys ages 14-17 post their cell phone number to their profile, compared with 14% of older girls. This gap is notable, given that older boys and older girls have the same rate of cell phone ownership (83% vs. 82%).

16% of teen social media users have set up their profile to automatically include their location in posts.

Beyond basic profile information, some teens choose to enable updates that automatically include their location when they post; some 16% of teen social media users say they have done this. Boys and girls and teens of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds are equally likely to say that they have set up their profile to include their location when they post. Teens who have Twitter accounts are more likely than non-Twitter users to say they enable location updates (26% vs. 13%).30

[I don’t share my location]

Other teens don’t mind having their location broadcast to others—particularly when they want to send signals and information to friends and parents. “If I could I would sometimes share my location, just so my parents know where I am” said one high school boy. Another high school boy wrote “Yes, I do share my location. I share my location to show where I am if I’m somewhere special, I don’t share my location if I’m just out to eat or home.”

Trends in Teen Facebook Practices

Among focus group participants, Facebook was the social media site with the greatest number of users, and thus the main site to consider for social media practices. Even those focus group participants claiming they did not have a Facebook account made comments indicating familiarity with the site. Many said their friends were a primary motivation for creating a Facebook account, while others said they created one to find out about events for school or extracurricular activities through Facebook.

Female (age 15): “And so after school the day before, someone said ‘oh, the assembly’s sure going to be fun.’ And I’m like, ‘what assembly?’ And they’re like, ‘the assembly that we’re performing in.’ ‘What assembly that we’re performing in?’ No one had remembered to tell me, because they had only posted it on Facebook. So after that I just got a Facebook to know what’s going on.”

Teens don’t think of their Facebook use in terms of information sharing, friending or privacy: for them, what is most important about Facebook is how it is a major center of teenage social interactions, both with the positives of friendship and social support and the negatives of drama and social expectations. Thinking about social media use in terms of reputation management is closer to the teen experience.

Female (age 15): “I think something that really changed for me in high school with Facebook is Facebook is really about popularity. And the popularity you have on Facebook transmits into the popularity you have in life.”

For many, Facebook is an extension of offline social interactions, although the online interactions take on forms specific to the features of Facebook. Focus group participants described (mostly implicit) standards relating to photos, tagging, comments, and “likes.” “Likes” specifically seem to be a strong proxy for social status, such that some teen Facebook users will try to upload photos of themselves that garner the maximum number of “likes,” and remove photos with too few “likes.”

[on Facebook]

Profile pictures are particularly critical, with some focus group participants participating in elaborate rituals to maximize the visibility in others’ newsfeeds and hence number of “likes” of their profile picture. As one focus group participant described it, when pictures are posted, at first individuals do not tag themselves. Only when some time has elapsed, and the picture has already accumulated some “likes”, will a user tag themselves or friends. The new tagging causes the photo to once again show up in news feeds, with the renewed attention being another opportunity to gather more “likes.”

[on Facebook]

Even as teens engage in these practices, they may perceive them as inauthentic and be embarrassed by their participation.

Female (age 15): “And there’s something that we call ‘like whores’ because it’s like people who desperately need ‘likes’ so there are a couple of things they do. First is post a picture at a prime time. And I’m not going to lie, I do that, too.” Male (age 16): “It depends how deeply they take what they find on the Internet or what they find on your Facebook. Because a lot of people either glorify themselves on Facebook or post stuff that doesn’t show what they’re really about, or them in real life.” Female (age 15): “You need to pretend that you’re something that you’re not.”

There are other reasons besides not enough “likes” for taking down photos, however.

Male (age 16): “I had this picture of me and my ex-girlfriend. I deleted it because like we were done.” Male (age 16): “I’ve deleted old pictures, because when I was younger, I thought they were cool. But now that I’m a little older, I’ve noticed that they’re just completely ridiculous.”

When trying to regulate the photos of themselves posted by others, focus group participants cited a variety of strategies for communicating about unwanted content.

[I’ve taken down photos from my Facebook timeline]

Uploading photos is closely linked to tagging, and focus group participants described the social delicacy of tagging others:

Male (age 13): “And tagging – I do tag people. But I’ve definitely had people freak out about a picture. So then I just either untag them or take the picture down.”

Similar to “likes,” postings and tags are used to establish a social position. Consequently, attacks on social positions come in the form of trying to use those tools against people:

[Facebook]

The threat of such an attack is one motivation for regulating content. Another is potential consequences from authority, which for older focus group participants often includes parents, other family members, college admissions officers and employers.

[I’ve taken down from my timeline]

Overall, a picture emerges where Facebook is a reproduction, reflection, and extension of offline dynamics. While “drama” is the result of normal teenage dynamics rather than anything specific to Facebook, teens are sometimes resentful toward Facebook from this negative association. Leaving the site altogether is viewed by some as an effective way of distancing oneself from the drama.

[Facebook]

Composition of Teens’ Online Social Networks

Gradations of privacy and publicity arise from the numerous choices that teens make as they construct their networks. In addition to choosing privacy settings, they choose (and sometimes even feel pressure to add) different people to their friend network. The size and composition of an individual’s friend network has great bearing on how private a “friends only” setting can be on a social media site.

Older teens tend to be Facebook friends with a larger variety of people, while younger teens are less likely to friend certain groups, including those they have never met in person.

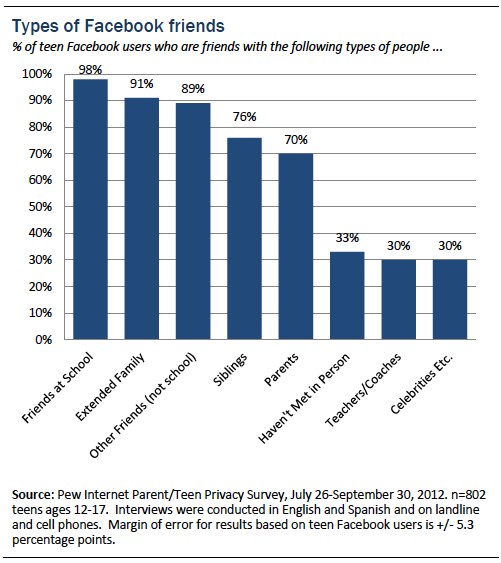

Teens, like other Facebook users, have a variety of different kinds of people in their online social networks, and how teens construct those networks has implications for who can see the material they share in those digital social spaces. School friends, friends from outside school and extended family members top the list of Facebook friends for teens:

- 98% of Facebook-using teens are friends with people they know from school.

- 91% of teen Facebook users are friends with members of their extended family.

- 89% are connected to friends who do not attend the same school.

- 76% are Facebook friends with brothers and sisters.

- 70% are Facebook friends with their parents.

- 33% are Facebook friends with other people they have not met in person.

- 30% have teachers or coaches as friends in their network.

- 30% have celebrities, musicians or athletes in their network.

Older teens are more likely than younger ones to have created broader friend networks on Facebook. Older teens are more likely to be friends with kids who go to different schools (92% compared with 82% of Facebook-using teens 12-13), to be friends with people they have never met in person (36% vs. 25%), and to be friends with teachers or coaches (34% vs. 19%). Girls are also more likely than boys (37% vs. 23%) to be friends with coaches or teachers, the only category of Facebook friends where boys and girls differ. African-American youth are nearly twice as likely as whites to be Facebook friends with celebrities, athletes or musicians (48% vs. 25%).31

Rural, suburban and urban youth also have somewhat different types of people in their Facebook networks. Suburban teens are more likely than urban or rural teens to be Facebook friends with their parents; 79% of suburban youth say their parents are part of their online social network, compared with 63% of rural youth and 60% of urban teens. Rural youth are more likely than all other teens to be Facebook friends with a brother or sister (90% of rural youth, compared with 75% of suburban and 70% of urban youth), and more likely than urban youth to be Facebook friends with members of their extended family (98% vs. 87%).

Teens with parents with lower levels of education (a high school diploma or less) are more likely than teens with college educated parents to be friends on Facebook with their siblings (81% vs. 69%).

Teens construct their social networks in a variety of different ways. In our online focus groups, we asked middle and high school students about who was in their online social network and how they decided who to friend (or not).

Many teens say they must “know” someone before they will accept a Facebook friend request from them, but teens expressed different thresholds for friending.

As one middle school girl noted “I know everyone on my friends list. My rules are that I have to know someone before I am friends with them on Facebook.” A middle school boy parsed it more specifically: “My friends on Facebook are about 90% all people I know, friends, family, and classmates. My rules are only people that I know can be my friends.”

But “knowing” someone can be defined a bit more broadly in social media. As one high school girl describes her network: “They are all people who I know, or who go to my school in my grade and therefore are people that I should know. Most of my close friends, my sister, and classmates. I don’t accept friend requests from people who I don’t know. I don’t friend people who just want it for Facebook apps and games, like Farmville.”

Parents are another challenging group for teens to manage on Facebook, and as such, youth have a number of different strategies.

Some are friends with their parents on Facebook and share their profiles fully with them. One high school boy describes his network: “My Facebook friends are close friends, family, and classmates. I do not add people I don’t really know. My parents can see everything I post and my whole profile.”

A middle school boy describes his tactics for managing his parents on Facebook: “My parents are my friends but they cannot see my full profile because I don’t want them to.”

And still other teens are not Facebook friends with their parents at all: “My parents aren’t my Facebook friends although my mom has a Facebook. If she was my friend, I wouldn’t let her see my profile because she comments on pretty much everything. It’s annoying.” As this participant indicates, many teens do not want to be friends with parents as much for netiquette reasons as for privacy protection.

[profile for friends]

A high school girl uses two profiles to manage her sharing in online vs. real world relationships: “I have two Facebooks: one for family/friends I know in person, and one for online friends. My “online friend” Facebook is less secure but also much less personal. My whole family isn’t able to see my full profile.”

Privacy Settings

Teens and adults have a variety of ways to make available or limit access to their personal information online. Within Facebook, the dominant social network among American youth, they can choose which people to friend and when to unfriend. They can choose to use default privacy settings or finely tune the privacy controls to limit who can see certain parts of their profile as well as restrict who can view individual posts. Retroactively, they can change the settings for content they have posted in the past or delete material from their timeline altogether. Among teen Facebook users, most restrict access to their profile in some way, but few place further limits on who can see the material they post. Twitter, by contrast, is a much more public platform for teens.

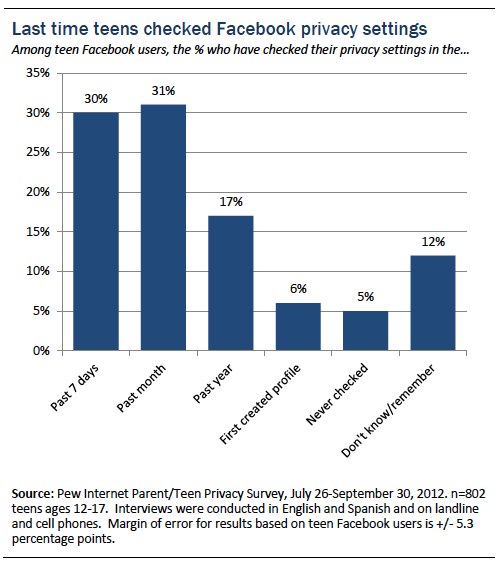

Most teens have checked their Facebook privacy settings relatively recently.

Three in ten (30%) Facebook-using teens have checked their Facebook privacy settings in the last seven days and close to another third (31%) have checked their privacy settings in the last month. A smaller percentage (17%) checked their Facebook privacy settings in the last year. About 6% said they checked them last when they created their profile and another 5% said they have never checked their Facebook privacy settings. And 12% said they could not remember or do not know the last time they checked their privacy settings.

Boys are slightly more likely than girls to say that they never check their settings (8% vs. 1%) or that they only check their settings when creating their profile (9% vs. 3%) Younger teens are also slightly more likely to say that they only checked their settings when establishing their profile (8% vs. 5%).

The bulk of teens keep their Facebook profile private. Girls are more likely than boys to restrict access to their profiles.

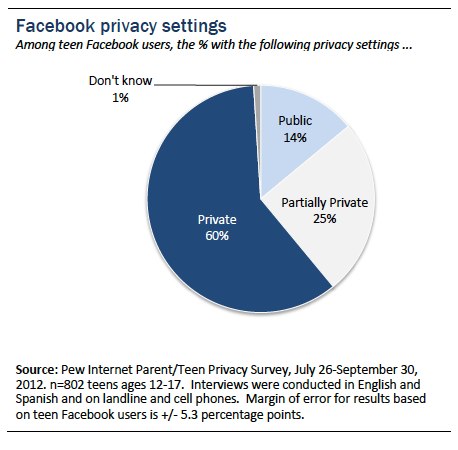

In findings virtually unchanged from when we first asked a similar question in 2011, 60% of teens ages 12-17 who use Facebook say they have their profile set to private, so that only their friends can see it. Another 25% have a partially private profile, set so that friends of their friends can see what they post. And 14% of teens say that their profile is completely public.32

Girls are substantially more likely to have a private profile than boys, while boys are more likely than girls to have a completely public profile. For private profiles, 70% of girls report Facebook profiles set to be visible to friends only, while 50% of boys say the same. On the flip side, 20% of boys say their profiles are public, while just 8% of girls report completely open Facebook profiles.

White teen Facebook users are just as likely as African-American teens to have public profiles. However, white teen Facebook users are more likely than African-American teens to have at least partially private Facebook profiles—29% of white youth, compared with 16% of African-American youth have profiles visible to friends of friends.33 Youth who live in urban areas are more likely than suburban dwellers (67% vs. 55%) have their profiles set to friends only.

Most teens express a high level of confidence in managing their Facebook privacy settings.

More than half (56%) of teen Facebook users say it’s “not difficult at all” to manage the privacy controls on their Facebook profile, while one in three (33%) say it’s “not too difficult.” Just 8% of teen Facebook users say that managing their privacy controls is “somewhat difficult,” while less than 1% described the process as “very difficult.”

Teens’ feelings of efficacy increase with age. While 41% of Facebook users ages 12-13 say it’s not difficult at all to manage their privacy controls, 61% of users ages 14-17 report that same level of confidence. Boys and girls report similar levels of confidence in managing the privacy controls on their Facebook profile.

Yet relatively few take steps to customize what certain friends can see. For most teen Facebook users, all friends see the same information and updates on their profile.

Beyond the general privacy settings on their profile, Facebook users can place further limits on who (within their network of friends) can see the information and updates they post. However, among teens who have a Facebook account, only 18% say that they limit what certain friends can see on their profile. The vast majority (81%) say that all of their friends see the same thing on their profile. This behavior is consistent, regardless of the general privacy settings on a teen’s profile. Boys and girls are also equally unlikely to restrict what certain friends can see on their profiles, and there are no significant differences between younger teens ages 12-13 and older teens ages 14-17.

[privacy settings]

This one-size-fits-all approach extends to parents; only 5% of teen Facebook users say they limit what their parents can see.

The vast majority of teen Facebook users (85%) say that their parents see the same content and updates that all of their other friends see. Just 5% say that they limit what their parents can see, while 9% volunteered that their parents do not use Facebook. Teens are equally unlikely to limit across all ages, racial and socio-economic groups.

In our online focus groups, teens were divided in their attitudes towards having their parents as Facebook friends and in the actions they did (or did not) take to limit their parents’ access to their postings. At one end of the spectrum are the open-book youth, who as this high school boy describes; “There isn’t any information that I would hide from my parents and not my friends, and vice versa.” Another high school boy distills it this way: “It’s all the same because I don’t have anything to hide.” Other youth are more concerned about having their parents see everything they post, with more worries around parents violating norms of communication: “My family isn’t able to see most of the things I post, mainly because they bother me,” said one high school girl. These teens shape what information is shared with their parents by limiting parental access to certain content.

Other teens observe that there are times when there is information that is fine for parents to know, but not friends. A high school girl explains: “I think that there are definitely some things that I would be fine with my parents knowing about that I wouldn’t want my friends to know.” Another high schooler couches the difference as one that revolves around trust: “Friends and parents each have different levels of trust associated with them for different things.”

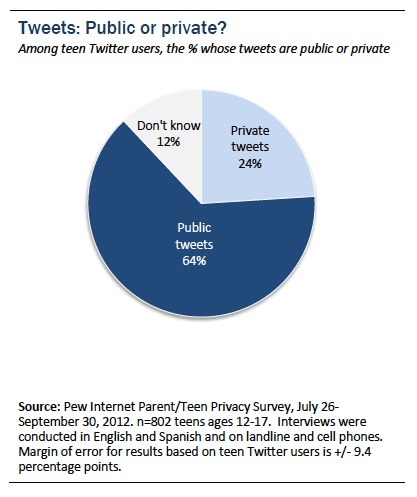

The majority of teen Twitter users have public accounts.

While there are many similarities in use of social media across platforms, each platform also has its own affordances that shape how youth use the technology and the types of privacy settings that are available to them. As noted in Part 1, Facebook is still the most popular social networking platform for American teens, but use of Twitter has grown rapidly in the last year. Today, one quarter (26%) of teen social media users say they have a Twitter account.34

Teens who have Twitter accounts generally report that their accounts are public; 64% of teen Twitter users say that their tweets are public, while 24% say their tweets are private. It is also notable that 12% of teens with Twitter accounts say that they “don’t know” if their tweets are public or private. The number of teen Twitter account owners is too small to report significant differences in privacy settings across various racial and socioeconomic groups. However, while boys and girls are equally likely to say their accounts are public, boys are significantly more likely than girls to say that they don’t know (21% of boys who have Twitter accounts report this, compared with 5% of girls).

Teens in our online focus groups reported a variety of practices around frequency of use and privacy on Twitter. Some teens check multiple times a day, like this middle school girl: “I use Twitter a couple times a day, just to see what other people are doing. My tweets are public.” Another middle schooler focuses his less frequent, more private use on following celebrities (a recurring theme among teen Twitter users): “I use my Twitter about twice a week to check out what celebrities are doing. My tweets are always private.” On the other end of the spectrum, there are more modest users of the service. Said one high school boy: “I have a Twitter account, but I rarely use it and it is not private.” Another high school boy reports, “I use Twitter about 3 times a month and I use it to make my followers laugh. My tweets are public.”

Teens’ Confidence in Their Own Privacy Regulation Online

Teens interviewed in focus groups overwhelmingly expressed confidence in their ability to manage and regulate their privacy online and feel their online disclosure of personal information is under control. However, much of this comes through regulating what content they post and not necessarily through their use of privacy settings, which some participants saw as irrelevant.

[profile or account]

Among those who did discuss their engagement with privacy settings, there was a great deal of variation. Some found them straightforward; others found them confusing.

[my account]

The source of many privacy and content concerns was indirect parental influence.

[parents]

In other cases, there was direct parental regulation, often through participants being friends with their parent(s) on Facebook. Much of this seemed to result in participants self-censoring, although we found one case of punishment for online actions. There were mixed opinions about explicit regulation, with some being appreciative, and others being resentful.

[I’ve gotten in trouble for something I posted]

In many cases, focus group participants understood, sympathized with, and respected their parents’ concerns. Sometimes focus group participants were even more worried than their parents about their online privacy. But sympathizing with parental concerns did not necessarily translate into agreeing with them. Some participants were confident they were more competent at regulating their content than their parents or other adults give them credit for.

[post something bad]

As mentioned earlier, what is most important to teens about social media sites is socializing with peers and those with shared interests. When they have bad experiences, they adjust their practices accordingly. While teens are influenced by parents and other adults to think about social media use in terms of information sharing and privacy, they do not always prioritize that perspective because it doesn’t account for and allow normal socializing. When teens do engage with privacy, it becomes a matter not just of engaging with privacy but also the world of adult expectations and responsibilities that is telling them the concept is important. Dealing with privacy, then, is more than just about privacy; it is about the process of being socialized into adult concerns and, ultimately, thereby becoming an adult.

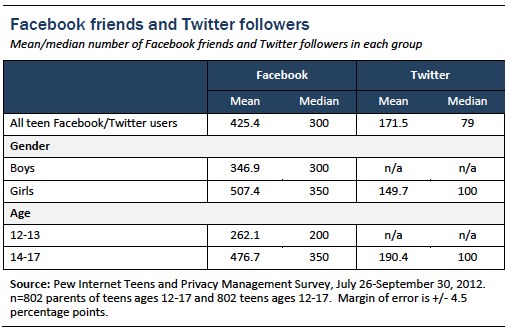

The typical (median) teen Twitter user has 79 followers.

Overall, teens have far fewer followers on Twitter when compared with Facebook friends; the typical (median) teen Twitter user has 79 followers.35 Looking at the data another way, 54% of teen Twitter users have more than 50 followers, while 44% have 50 or fewer followers. Just one in three (34%) say that they have more than 100 followers on Twitter. Also notable is the fact that only 2% say they don’t know how many followers they have. That compares to 12% who say that they don’t know if their tweets are public or private. In general, girls who are Twitter users are more likely to have a larger number of followers when compared with boys who are Twitter users; 68% of girls have more than 50 followers, compared with 36% of boys.36 However, the number of teen Twitter users is too small to report significant differences in followers across various racial and socioeconomic groups.

[follow me]

The online focus group data also sheds light on teens’ experiences of the differences between Facebook and Twitter. Some teens use the two sites in very similar ways. As one middle school girl describes, “I have a Twitter and I use it almost every day. I put the same things on it like I do for Facebook.” Some teens have their various social media accounts linked so that material posted to one account automatically cross posts to the other, while others more finely curate which images and posts go to which site.

[Twitter and Facebook]

And while many teens echoed that Twitter feels more public to them, others suggested that “Facebook is more public because I think more people use Facebook.” Another high school boy wrote: “I think Facebook is more public than Twitter because there is more information on Facebook than Twitter.”

On Facebook, network size goes hand in hand with network diversity, information sharing, and also personal information management

In order to fully understand the implications of the content that teens share on social media, it is vital to understand the size and composition of their online social networks. Sharing information about yourself with a select group of 100 in-person friends is very different from sharing the same information with 1000 people including adults and peers of varying degrees of closeness and real-world contact.

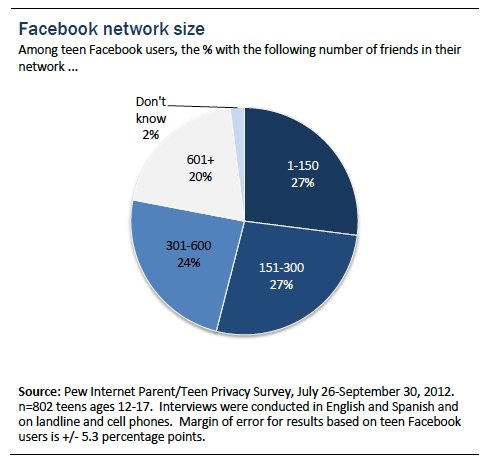

The typical (median) teen Facebook user has 300 friends. Among older teens and girls, the median increases to 350 friends.

Teen Facebook users have an average (mean number) of 425.4 friends, with the typical (median) teen Facebook user having 300 friends. As noted above, Twitter networks tend to be substantially more compact by comparison—teen Twitter users have an average of 171.5 followers, with the typical (median) teen user having 79 followers on Twitter. Girls and older teens tend to have substantially larger Facebook friend networks compared with boys and younger teens.37

In addition to being older and more heavily female, teens with larger Facebook networks also tend to have a greater diversity of people in their friend networks and to share a wider array of information on their profile. Yet even as they share more information with a wider range of people, they are also more actively engaged in maintaining their online profile or persona.

For the analysis that follows, we will divide the teen Facebook population into quartiles based on the number of friends they have on the site—those with 150 or fewer friends (this group makes up 25% of the teen Facebook user population), those with 151-300 friends (25%), those with 301-600 friends (23%) and those with more than 600 friends (19%).38

Teens with large Facebook friend networks are more frequent social media users and participate on a wide diversity of platforms in addition to Facebook

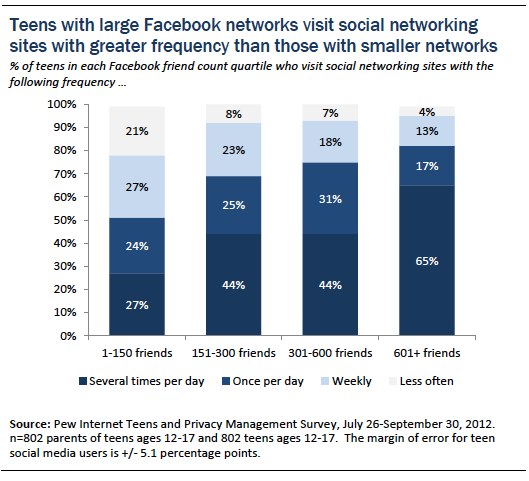

Teens with a large number of Facebook friends exhibit social networking site usage patterns that differ sharply from those of teens with smaller friend networks, starting with the fact that these teens spend more time using social networking sites in general. Some 65% of teens with more than 600 friends on Facebook say that they visit social networking sites several times a day. By comparison, just one quarter (27%) of teens with 150 or fewer Facebook friends visit social networking sites with similar frequency.

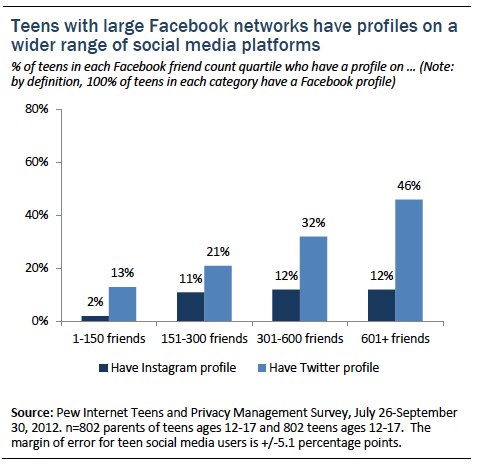

In addition to using social networking sites of any kind with greater frequency than teens with relatively small friend networks, teens with a larger number of Facebook friends also tend to maintain profiles on a wider range of platforms outside of Facebook itself.

This is especially true for Twitter use, as teens with more than 600 Facebook friends are more than three times as likely to also have a Twitter account as are those with 150 or fewer Facebook friends. Indeed, some 18% of teens with more than 600 friends on Facebook say that Twitter is the profile they use most often (although some 73% of these teens say that Facebook is their most-used social networking profile).

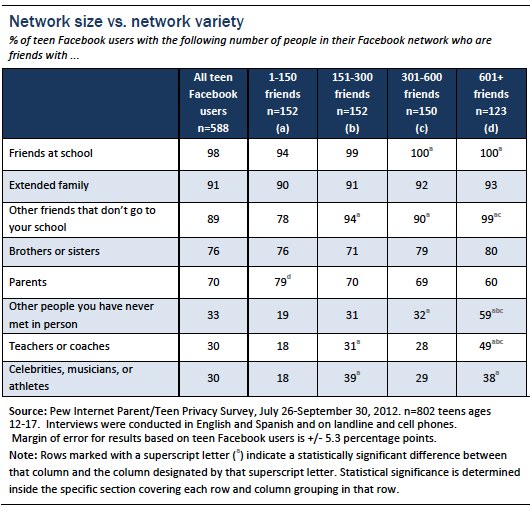

Teens with larger Facebook networks tend to have more variety within those networks.

Almost all teen Facebook users (regardless of whether they have a small or large number of friends) are friends with their schoolmates and extended family members. Regardless of network size, teen Facebook users are equally likely to say they have siblings as friends in their networks. With the exception of those with the smallest friend networks, most teens are also equally likely to be friends with public figures such as celebrities, musicians or athletes.

However, certain groups become more prominent as the size of teens’ networks expand. Teen Facebook users in the largest network size quartile (those with more than 600 friends in their network) are more likely to be friends on Facebook with peers who don’t attend their own school, with people they have never met in person (not including celebrities and other “public figures”), as well as with teachers or coaches. Most strikingly, teens with more than 600 Facebook friends are nearly twice as likely as the next quartile to have teachers or coaches, or other people they haven’t met in person in their friend networks.

On the other hand, teens with the largest friend networks are actually less likely to be friends with their parents on Facebook when compared with those with the smallest networks—although a majority of teens are friends with their parents on Facebook across all network size groupings.

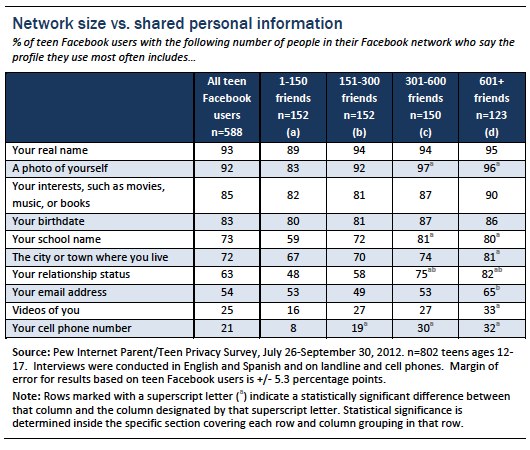

Teens with larger friend networks tend to share a wider variety of personal information on their Facebook profile.

Along with expanding their networks to include a greater variety of friends, teens with larger friend networks also tend to share a wider variety of personal information on their Facebook profile. Teens with an above-average number of friends are more likely to include a photo of themselves, their school name, their relationship status, and their cell phone number on their profile compared to teens with a below-average number of friends in their network.

Concerns about third party access on social media

Most teen social media users say they aren’t very concerned about third-party access to their data.

Social media sites are often designed to encourage sharing of information—both to keep users engaged and returning to find new content and also to gather more information to share with advertisers for better ad targeting and other forms of data mining. There is an ongoing debate over these practices—over how much users are aware that their information is being shared, whether minors should be the subject of data collection that is ultimately shared with and sold to third parties, and whether users appreciate that targeted ads and other forms of data collection allow them free access to certain websites and services. The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) even as it is thought of today as a law built to safeguard children’s physical well-being, began as an attempt to protect children under 13 from having their personal information collected for business purposes without their parent’s permission.

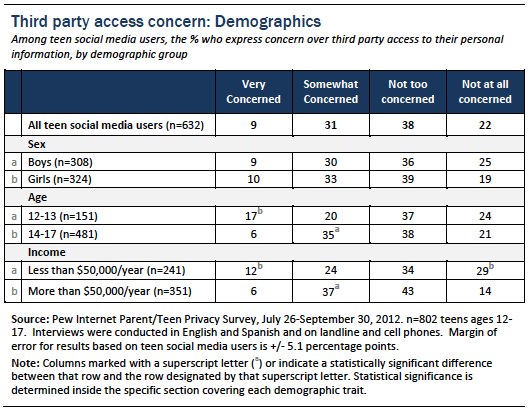

Overall, 40% of teen social media users say they are “very” or “somewhat” concerned that some of the information they share on social networking sites might be accessed by third parties like advertisers or businesses without their knowledge. However, few teens report a high level of concern; 31% say that they are “somewhat” concerned, while just 9% say that they are “very” concerned.39 Another 60% in total report that they are “not too” concerned (38%) or “not at all” concerned (22%). Younger teen social media users ages 12-13 are considerably more likely than older teens (14-17) to say that they are “very concerned” about third party access to the information they share (17% vs. 6%). Girls and boys report the same levels of concern.

Teens from lower income families are more likely to express strong views about third party access to data than teens living in higher income households. Teens living in lower income households (those with parents earning less than $50,000 annually in household income) are more likely than those living in higher-earning families (earning $50,000 or more per year) to say that they are very concerned (12% vs. 6%). However, teens living in lower income households are also more likely than those living in higher-income families to say they are “not at all” concerned about third parties accessing their personal information (29% vs. 14%). In contrast, teens from in higher income families are more likely than those in lower-earning households to say that they are “somewhat” concerned by third party access (37% vs. 24%). Teens’ concern levels follow a similar pattern of variation according to their parents’ education level.

As might be expected, teens who have public Facebook profiles are more likely to say they are not concerned about third parties accessing their personal information online, when compared with teens who have more locked down Facebook profiles. Among teens with public profiles, 41% are “not at all concerned” about third party access to their information, compared with 13% of teens with partially private profiles and 20% of teens with private profiles who are not at all concerned about third parties.40 Teens with partially private profiles are more likely to say they are “not too concerned” or “somewhat concerned” about third party access than teens with more public Facebook profiles.

Teen Twitter users are more likely than those who do not use Twitter to express at least some level of concern about third party access to their data; 49% of teen Twitter users say they are “somewhat” or “very” concerned about third party access, compared with just 37% of teens who do not use Twitter.

Looking at network size, there are no clear increases or decreases in concern level relative to the number of friends a teen has in his or her Facebook network.

Insights from our online focus groups suggest that some teens do not have a good sense of whether or not the information they share on a social media site is being used by third parties.

[Facebook]

“I don’t know if Facebook gives access to others. I hope not.”

[Facebook]

“It depends on what kind of profile information they’d share,” wrote a high school girl. “If it was only my age and gender, I wouldn’t mind. If they went into detail and shared personal things, I would mind!”

Another high school boy stated: “I don’t think it would be fair because it is my information and should not be shared with others, unless I decide to.”

Other teens were more knowledgeable about information sharing with third parties, and were often philosophical about the reasons why that information might be shared. Noted one high school boy: “I think that Facebook gives apps and ads info to try and give you ads that pertain to you.” Another middle school boy understood why a social media site might share his information, even if he wasn’t always happy about it: “I know that Facebook gives access to my info to other companies. I don’t like that they do it, but they have the right to so you cannot help it.”41

Similar findings were echoed in our in-person focus groups:

Advertisers and Third Party Access

Advertisements and online tracking by companies does not appear to be a major concern for most focus group participants, although a few find them annoying, and others see these company practices as inevitable.

[location tracking and access to content by companies]

Some teens even enjoy the benefits of “liking” certain companies and receiving advertisements, or allowing apps to access private information to use certain features. Those participants expressed the feeling that the risks are minimal, or that they have “privacy through obscurity.”

[on Facebook]

Without having experienced negative consequences or seeing what those negative consequences might be, teens do not seem to be overly concerned about advertisers and third parties having access to their information. If they see that they can get benefits from sharing information, they are often willing to do so.

81% of parents are concerned about how much information advertisers can learn about their child’s online behavior.

Even as teens report a relatively modest level of concern about third parties such as advertisers or businesses accessing the personal information they post online, parents show much greater levels of concern about advertisers accessing information about their child. Parents of the surveyed teens were asked a related question: “How concerned are you about how much information advertisers can learn about your child’s online behavior?” A full 81% of parents report being “very” or “somewhat” concerned, with 46% reporting that they are “very concerned.” Just under one in five parents (19%) report that they are “not too” or “not at all” concerned about how much advertisers could learn about their child’s online activities.