Introduction

There is a growing policy discussion about how government should act in an environment in which personal information—about both children and adults—is widely collected, analyzed and shared as a new form of currency in the digital economy. Many details about the lives of online (and offline) Americans can be found using simple search queries and their traits and interests are often easily discovered through their social media posts and through the social networks they build. Unless they take specific measures to prevent certain information from being tracked, internet service providers track much of their online behavior and amass this information to deliver ads to them. Most of the free services available online involve a trade off: In return for being able to access services online for free, information is collected about users to deliver targeted advertising.5

In the U.S., websites that are collecting information about children under the age of 13 must comply with regulations established under the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act. In effect since 2000, these rules have required website operators to obtain parental consent before gathering information about children under the age of 13 or giving them access to “interactive” features of the site that may allow them to share personal information with others. Some of the most popular web properties, such as Facebook, have opted to avoid the parental consent framework and instead forbid all children under the age of 13 from creating accounts. Yet, previous studies from the Pew Internet Project and other media scholars have suggested that many underage children continue to use social media, many lie about their age, and in some cases, parents are helping their children circumvent restrictions to gain access to the sites they wish to use.6

The Federal Trade Commission recently proposed changes to COPPA that would address some of the radical technological changes that have occurred since the law was first written. The proposed modifications include a new requirement that third-party advertisers and other “plug-ins” will have to comply with COPPA, and the definition of “personal information” has been expanded to include persistent identifiers such as cookies and location information that includes a street, city or town name. With respect to age, websites that cater to a mixed-age audience (such as Disney.com) will now be allowed to “screen” a user’s age and only be required to provide COPPA protections for users age 13 and under. However, sites that are directed at users under 13 will still have to treat all users as children.7 Nearly 100 public comments have been filed in response to the FTC’s latest proposed changes to COPPA—some of them critical of the burdens these changes may place on small businesses such as app developers, while others filed in support of the updates, noting that new definitions and clarifications help strengthen the law’s original goal of helping to protect children’s privacy online.8 The Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project does not take positions on policy issues, and as such, does not endorse or oppose any of these proposed changes.

Over several years, the Pew Internet Project talked to teens and their parents about issues related to privacy, identity, and information sharing. This summer and early fall, the Pew Internet Project conducted a nationally representative survey of parents and their teenage children that focused on some of these issues. The results from the parents section of the survey are reported here.

In collaboration with the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard, this report also includes quotes gathered through a series of exploratory in-person focus group interviews about privacy and digital media, with a focus on social networking sites (in particular Facebook), conducted by the Berkman Center’s Youth and Media Project. Between May and December 2011, the team, led by the project’s Director Sandra Cortesi, conducted 16 focus group interviews with roughly 120 students. The focus groups included youth in grades 6-12 from diverse schools and varying socio-economic backgrounds, including Boston, Cambridge, Brookline and New York. This report includes selected quotes from participants that illustrate various youth perspectives toward parent participation in social media spaces. Future reports issued by the Pew Internet Project and the Berkman Center will include extensive reporting of the teen responses to the national survey, as well as additional qualitative research results.

Parental Concerns and Actions

Interaction with strangers worries parents. But they are also anxious about the data advertisers are collecting about their children’s online behavior and the broader impact that online activity might have on their child’s reputation.

Parents have consistent and relatively high-level concerns about a variety of problems their children face both online and offline. A 2011 Pew Internet & American Life Project survey found that 47% of parents were “very concerned” about their child’s exposure to inappropriate content through the internet or cell phones. Likewise, the same study showed 45% of parents expressing high levels of concern about the way “teens in general treat each other online or on their cell phones.” Of less concern was the worry that their child’s internet or cell phone use was taking time away from face-to-face interactions with friends and family; just 31% said they were “very concerned” about this. Yet, the internet and cell phones are hardly the only—and perhaps not the primary concern—on parents’ minds. For example, a recent analysis of the EU Kids Online survey noted that parental anxiety about internet-related risks tended to fall in the middle of the spectrum of concerns and did not outweigh other offline worries such as how their child was doing in school or the potential of physical harm due to a car accident.9

Strangers

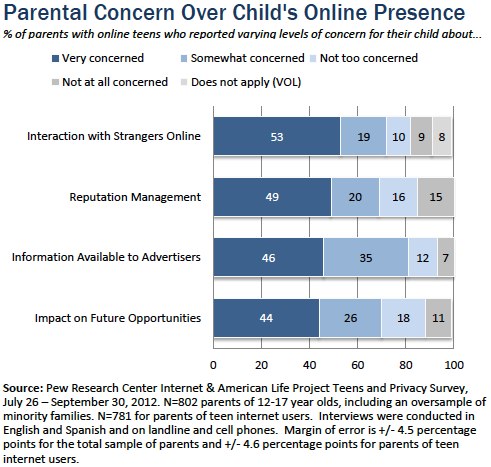

Parental concerns about their child’s interaction online with people they do not know are high. More than half of parents (53%) say they are “very concerned” about how their child interacts online with people they do not know, while another 19% say they are “somewhat concerned.” Even higher levels of concern about interaction with strangers online have been reported in similar studies when possible harm to the child is mentioned.10

Parental worries about online interaction with people their child does not know are fairly universal across various demographic groups, with a few notable exceptions.

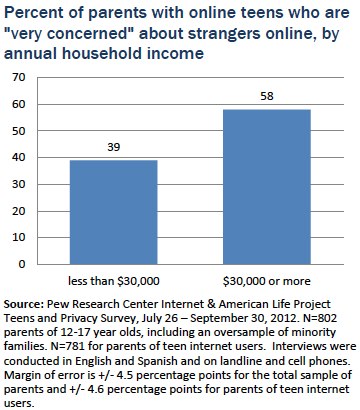

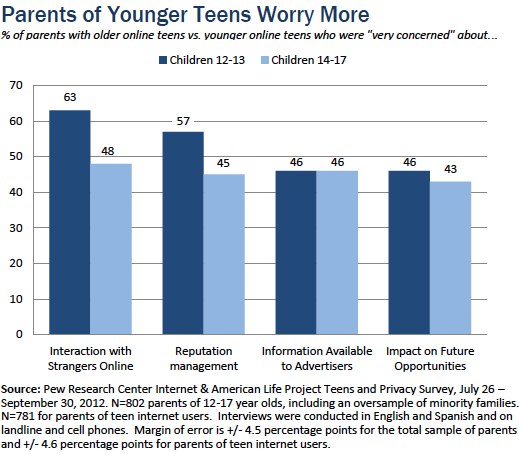

Parents of younger teens (ages 12-13) express greater levels of concern about this issue when compared with parents of older teens (14-17); 63% of parents of younger teens say they are very concerned about interactions with people they do not know online vs. 48% of parents of older teens. And parents living in low-income households (earning less than $30,000 per year) express significantly lower levels of concern about their children’s online interactions with people they do not know; just 39% say they are “very concerned” about this issue, compared with about six in ten parents in higher-earning households. Parents of teenage boys and girls express equal levels of concern about their child’s interaction with people they do not know online.

Advertiser practices

When asked about the information that advertisers can gather about their child’s online behavior, parents’ concern levels rival and sometimes even exceed worries about their child’s interaction with people they do not know online. While 46% of parents said they were “very concerned” about how much information advertisers can learn about their child’s online behavior, another 35% said they were “somewhat” concerned. Taken together, that represents 81% of all parents in our survey. By comparison, the combined levels of parental concern regarding their children’s interactions with people they do not know amounts to 72% of all parents.

Parents of younger teens are more likely than those with older teens to express some level of concern about the issue of advertisers tracking their child’s online behavior (87% vs. 77%). And parents in the lowest income households are less likely to express concern about advertisers when compared with those in middle-income households; 72% of parents earning less than $30,000 per year express some level of concern, compared with 87% of those with annual household incomes of $30,000 to just under $75,000 per year.

When looking more closely at those who express the highest degree of worry, again, African-American parents stand out; 62% say they are “very concerned” about the information advertisers can gather compared with 47% of white parents. Yet, when combining responses for those who are “very concerned” and “somewhat concerned,” there are no significant differences between African-American and white parents; about eight in ten parents in both groups express some level of concern about the information advertisers can learn about their child’s online behavior.

Reputation management

Reputation management is a complex affair for anyone online, and teenagers face especially daunting challenges as they navigate the rocky road of adolescent development and youthful blunders in an unforgiving digital environment. Parents are just as concerned about this aspect of online life as they are about their child’s interaction with strangers. Some 49% of teens’ parents said they were “very” concerned about how their child “manages their reputation online.” Another 20% said they were “somewhat” concerned.

Academic and professional opportunities

More specifically, parents were also asked how concerned they were about the way their child’s online activity “might affect their future academic or employment opportunities.” Some 44% of parents said they were very concerned about these future implications, while 26% said they were somewhat concerned.

African-American parents of teenaged children are considerably more likely to express high levels of concern about the way their child’s online activity might affect their future education or job opportunities; 59% said they were “very concerned” about this compared with 41% of white parents. Here again, parents living in lower-income households expressed lower levels of concern about this issue, but the same was true of those living in the highest-income households. Instead, those living in middle-income households (earning between $30,000 and $74,999 per year) are most likely to worry about the future implications of their child’s online behavior.

Parents’ use of social media grows

One of the major online places where parents and their teens encounter each other is on social networking sites. These are also places where there is concern about the way teens interact with others and where they share information about their lives.

In this survey, we find growing parental adoption of social networking sites (SNS) and growing conversation in families about what happens on those sites.

Among all parents who have a child between the ages of 12-17, 66% now say they use a social networking site, up from 58% in 2011.11

Mothers and fathers are equally likely to use social networking sites (69% vs. 63%), but there is great variation according to the parents’ ages. For parents under 40, 82% say they use social networking sites like Facebook or Twitter, while only 61% of parents over age 40 use the sites. Parents who are college-educated also exhibit higher levels of engagement with social media; 74% of parents who are college grads use social networking sites, compared with 59% of those who have not attended college. In contrast, parents across all income groups are relatively consistent in their adoption of social media.

Teens have mixed feelings about being friends with their parents on Facebook.

Previous research from the Pew Internet Project has shown that when both parents and teens use social networking sites, the vast majority friend each other; in 2011, 80% of parent social media users whose children were also users of social media have friended their child on the sites.12 However, Berkman’s focus group discussions with teens revealed that they have mixed feelings about being friends with their parents on sites like Facebook.

Many teens have a positive attitude about being friends with their parents. Some youth are friends with their parents or their parents’ friends on Facebook and don’t seem concerned about their parents seeing their posts. In fact, some like being Facebook friends with their parents:

Female (age 13): “I actually really love being friends with my parents because we have like our own group on Facebook, so it’s very good, like, to communicate. We don’t have to send emails and things like that, just quick links I want to send them or fun things, pictures, things like that you can just send it there. They’re so popular on Facebook, it’s funny.”

[friends with me on Facebook]

[mom]

Male (age 14): “We don’t have to worry much about what we put up, because what we put up we know that our family is going to see, so it’s like if there’s something that we don’t want—I remember like my mom told me don’t put anything you wouldn’t want your grandparents to see or something.”

Female (age 13): “I’m also friends with some of my parents’ friends. It’s cool.”

At the same time, some youth seem to prefer not to friend their parents. They friend them only because it’s expected of them:

Female (age 13): “My mom got a Facebook when I got a Facebook and she friended me so I guess kind of to keep an eye on me. I don’t want to friend her but she like friended me.”

[friends with her]

And some youth whose parents are not yet on Facebook seem to be grateful for that:

Female (age 13): “My parents don’t have a Facebook. Thank God.”

Female (age 14): “The day my father gets on Facebook is the day I’ll be out of Facebook.”

The reason for not wanting to be friends with their parents on Facebook is not necessarily that they want to hide something from their parents:

Female (age 12): “It’s not that you necessarily have anything to hide, it’s just everyone’s different around their family members than they are with their friends.”

Female (age 13): “I know for some of my friends on Facebook, some of their family members are really obnoxious. Someone will change their status update to “going to the park” and then you’ll see eighty family members saying, “Have fun at the park.”

Yet, some teens who have friended their parents on Facebook restrict their parents’ access to information or self-censor the content they post:

Interviewer: “How about on Facebook, are your family members your friends?” Female (age 13): “They are but I have them blocked from my page, so they can’t see my page or anything on it.”

[…]

Interviewer: “Whatever the reason, the result is you post less stuff to Facebook.” Female (age 13): “Yeah.” Interviewer: “And it’s because in part you don’t want people who are older looking at everything you’re posting.” Female (13): “My family members, yeah.” Interviewer: “Is that true for other people?” Other youth (ages 12-13): “Yeah.”

59% of the parents of teen social media users say they have talked with their child because they had concerns about something posted to their profile or account. And 39% have helped their child with privacy settings.

In our 2011 survey, we found that 87% of parents of online teens said they had talked with their teen about the things he or she had been doing online. Those discussions could have been positive, negative or neutral, and they could have referenced a wide array of online activity. In the latest survey, we wanted to ask more specifically about social media and the extent to which conversations were being prompted by concerns about something posted to the teen’s profile or account.

It turns out that considerable numbers of parents have actively intervened in their child’s social networking environment. Six in ten (59%) parents of teen social network users say they have talked with their teen because they had concerns about something that was posted to their child’s profile or account. What is most striking about the findings for this question is the lack of variation across groups; these conversations prompted by concerns over social media content are equally prevalent among a wide array of parents from different backgrounds. Less surprising is the fact that parents who use social media themselves are more likely than non-users to have these conversations with their children (65% vs. 45%).

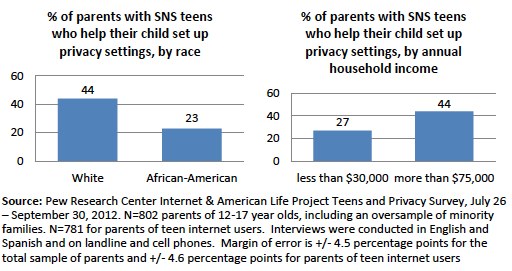

Another kind of intervention relates to privacy settings. Some 39% of parents who have a child that uses social network sites say they have helped their child set up privacy settings for their account. Parents of younger teens who use social media are far more engaged in helping with privacy settings; 49% of parents of younger teens have assisted with privacy settings for their child’s account, compared with 35% of parents of older teens. Most of this variation is due to parents of 12-year-olds. There are no significant differences according to the gender of the child.

White parents are almost twice as likely as African-American parents to help their child set up privacy settings (44% vs. 23%). Parents living in the highest-income households (earning $75,000 or more per year) are more likely than those in the lowest-income households (earning less than $30,000 per year) to say that they have helped their child with privacy settings on a social network site (44% vs. 27%).

Half of parents who are social media users have commented or responded directly to something posted on their child’s social network profile.

Whether driven by concerns or a desire to show approval or support, 50% of parents who use social media (and also have teens who use the sites) say they have commented or responded directly to something that was posted to their child’s profile or account. Mothers and fathers are equally likely to engage with their child’s profile in this way. Similarly, there are no clear variations by the age or gender of the child or across various socio-economic groups.

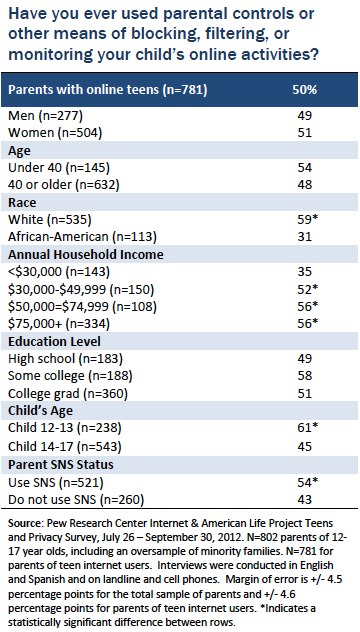

Half of parents of online teens say they use parental controls and other means of blocking, filtering or monitoring their child’s behavior

In the latest survey, 50% of parents with online teens said they use parental controls or some other means of blocking, filtering or monitoring their child’s online activity. That represents a statistically insignificant difference from the 54% who reported doing so in 2011. As we have noted in previous reports, overall, parents are more likely to favor less technical steps for monitoring their child’s online behavior, such as checking to see what websites their child has visited or what information is available online about their child.13

Use of parental controls is much higher among white parents, those who have attended college, and those living in households earning more than $30,000 per year. All of these trends are consistent with the previous survey, except for a notable decrease in usage among African-American parents. In 2011, African-American parents were just as likely as white parents to say they use parental controls (61% vs. 58%). In the 2012 survey, they were half as likely to report use of these controls (31% vs. 59%).

Parents of younger teens (12-13) are considerably more likely than parents of older teens (14-17) to use technical tools like blocking, filtering and monitoring (61% vs. 45%). Parents of younger teen girls are among the most likely to employ parental controls; fully 65% do so. These variations according to the age of the child also represent a shift from the previous survey; in 2011, parents of younger and older teens were equally likely to use controls.

Looking at the parent’s age, there are no notable differences in the likelihood that they will use parental controls. However, parents who are social media users are more likely than non-social media users to say they employ some form of parental controls (54% vs. 43%).

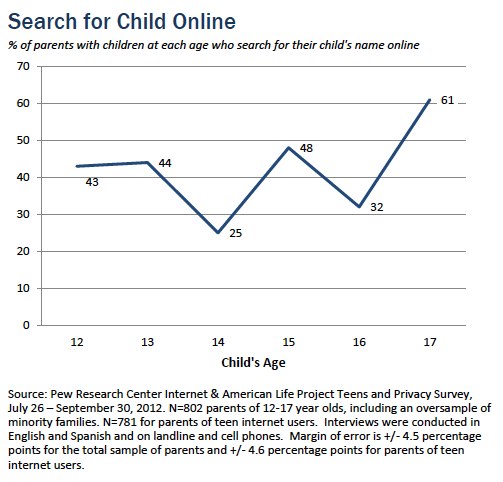

Four in ten parents of online teens have searched for their child’s name online to see what information is available about them.

Some 42% of parents of online teens say they have searched for their child’s name online to see what information is available about them. Previous surveys have indicated that a majority of parents have “checked to see what information is available online” about their child, but this could involve everything from viewing private websites associated with a child’s school to checking Facebook profiles. Those who have gone so far as to type their child’s name into a search engine to see what results may be available to a wider public represent a more modest segment of parents.14

Fathers and mothers are equally likely to have searched for their child’s name online, as are parents of different ages. However, when it comes to the age of the child, the most notable shift happens at age 17, when most teens (and parents) are negotiating the college admissions process. Among parents with a 17-year-old child, 61% say they have searched for their child’s name online to see what information is available about them.

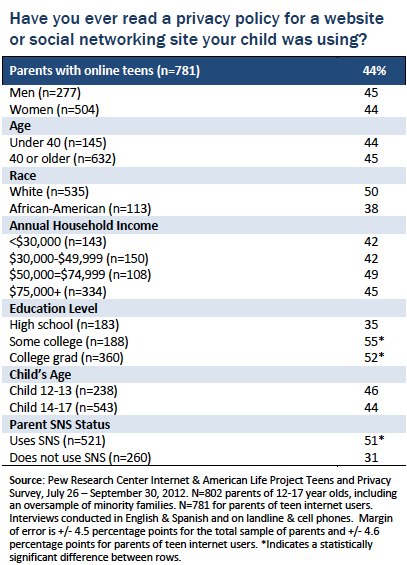

44% of parents of online teens say they have read a privacy policy for a website or social network their child was using

Almost half (44%) of parents of online teens say they have read a privacy policy for a site their child was using. Among parents of younger teens (ages 12-13), 46% say they have read a privacy policy for a site their child visited. Parents who have not attended college report lower levels of reading; just 33% of parents with a high school degree or less say they have read a policy for a site their child was using, compared with 53% of those with at least some college education. Parents who use social media themselves are also more likely than non-users to read privacy policies on the sites their children are using (51% vs. 31%). Parents who express some level of concern about how much information advertisers can learn about their child’s behavior online are more likely than those who are “not at all” or “not too” concerned to read privacy policies (47% vs. 33%).