Predictions and Reactions

Prediction: By the year 2020, virtual reality on the internet will come to allow more productivity from most people in technologically- communities than working in the ‘real world.’ But the attractive nature of virtual-reality worlds will also lead to serious addiction problems for many, as we lose people to alternate realities.

An extended collection hundreds of written answers to this question can be found at:

http://www.elon.edu/e-web/predictions/expertsurveys/2006survey/virtualreality.xhtml

Overview of Respondents’ Reactions

Those who have technology available to them will spend more time immersing themselves in increasingly-sophisticated, networked synthetic worlds for work and entertainment. They will be experiencing “virtual” reality more. “Addiction” is a word that bothered some respondents, but others thought it is a likely consequence for some people.

What is virtual reality? Professionals in the field of VR research today say it is the immersion of human sensory channels within a computer-generated experience.34 This can also be explained by saying VR allows one to be in a place without really being in that place. Others consider people who “lose” themselves in today’s online role-playing games and even in online chats to be experiencing virtual reality and even “full-immersion VR” because it envelopes their minds to the point where they are not conscious of anything else; still, some don’t see this as true VR.

In this survey, respondents’ replies reflect the full range of current popular definitions of VR – from the point of view that “it’s already happening” (mostly in people’s full-scale immersion in today’s massively multi-player online role-playing games – MMORPGs) to the idea that the only true VR includes a full-scale 3-D touch-sight-sound experience, generally using highly specialized equipment to shut out “reality” and give one a virtual “presence” in another place.

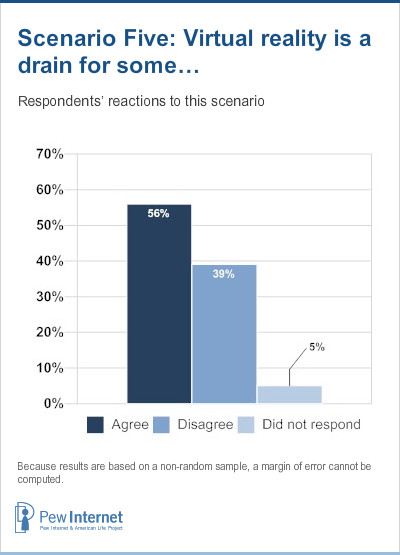

A majority of survey participants agreed with the proposed 2020 scenario, with many declaring it is already a reality. Most who disagreed with the projection defined “virtual reality” in a more formalized, 3D, all-senses format that has yet to be perfected. Some respondents also took issue in various forms with the use of the terms “reality” and “addiction.”

Only a few respondents chose to focus their elaborations on the idea that VR work will allow more productivity than work in the “real” world. Richard Yee, competitive intelligence analyst for AT&T,35 wrote, “By 2020, the term ‘virtual reality’ will be outdated. The Internet will become more sensory, attracting more applications that will appeal to end-users. The Internet will be surrounded by more applications, where it will become more stimulating. In turn, more productivity will be driven from the new ideas originating from such stimulation.”

Ben Detenber, an associate professor at Nanyang Technological University, responded, “VR will only increase productivity for some people. For most, it will make no difference in productivity (i.e., how much output); VR will only change what type of work people do and how it is done.”

Glenn Ricart, a member of the board of trustees of the Internet Society, wrote, “Various kinds of computer-mediated business models/productivity models/configurable electronic workspaces will be key productivity enhancers.” However, he also added, “There will be an increasing problem with people ‘disconnecting’ during their so-called leisure time and immersing themselves in purely virtual realities for entertainment purposes. We’ve already seen how these can be addictive, and, by 2020, the technological capability for them might be near ubiquitous – leading to perhaps an entire generation ‘opting-out’ of the real world and a paradoxical decrease in productivity as the people who provide the motive economic power no longer are in touch with the realities of the real world.”

Respondents were sensitive to the word “addiction.”

The use of the word “addiction” influenced most respondents to address this angle of the scenario exclusively in their responses. As author and sociologist Howard Rheingold noted, “The way the question is worded embeds some assumptions. I have a serious addiction to reading; is that a social problem? Has the world ‘lost’ me?”

Writer Fred Hapgood responded, “Of course it is totally arbitrary as to who gets to call whom an addict.” And Toby Miller of the UC-Riverside wrote, “Addiction is a bizarre metaphor to apply to forms of labor and leisure other than drugs. It buys into the medical model’s attacks into popular culture.”

Respondents predicting that addiction will be evident in 2020 were pretty much divided into two camps: those who imply that an addiction to VR can simply be classed with other addictions such as alcohol, drugs and gambling; and those who see VR in a different light as a new concern.

“There are lots of ways to get addicted, and the list changes with time,” wrote Roger Cutler of the Worldwide Web Consortium and Chevron’s Information Technology Division. “It is very unlikely that this source of addiction will have any magic power that others don’t.” Robin Gross, executive director of IP Justice, responded, “VR is no different than offline temptations.” Joe Bishop, a vice president with Marratech, wrote, “We lose some folks to gambling and drugs now. And if drug addiction isn’t an alternative reality I doubt I know what is. I doubt that this will be a serious problem.”

“We won’t ‘lose’ people,” argued Randy Kluver, director of the Institute for Pacific Asia at Texas A&M University and former executive director of the Singapore Internet Research Centre at Nanyang Technological University. “But people will likely find virtual reality more interesting than the offline world. There will be a few people who don’t interact much with the outside world, but there is something in human nature that craves real, physical closeness.”

Scott Moore has been working with virtual worlds for 10 years as the online community manager for the Helen and Charles Schwab Foundation. He wrote, “I disagree with any large-scale doom prediction surrounding virtual-reality addiction. However, such addiction will progress very much as addictive drugs do. Right now, we see this with the large corporate-based virtual worlds which are like cocaine for some – expensive to produce and to consume. As the tools for creating such places become cheaper and easier to access, we will see lower-quality virtual worlds that will have a wider reach to people with less disposable income (starting with the middle-middle classes and working down). We can see the very beginnings of this progression with the many free social-networking services. Some people will be completely sucked in and their lives ruined, much as what happens for drugs now. However, the toll will still be far less than the damage to lives and communities that chemical drugs can do.”

Torill Mortensen of Volda University College in Norway wrote, “First, there is nothing virtual about digitalised space. It has real-life effects, rewards, and problems. Second, what do we lose people to today? Is it better to go jump off a mountainside for your kicks or do drugs than to spend it in some digital version of reality that feels better and more rewarding? The main problem isn’t that ‘virtual worlds’ are addictive; it is that the physical world is not sufficiently challenging and rewarding. Blaming the media should not be a way out of fixing the very real social problems the world faces.”

Bryan Trogdon, president of First Semantic – a company working on a realization of the Semantic Web – responded, “Wall-sized monitors in conjunction with speech recognition, artificial intelligence, wireless broadband and computer power will take us from television to teleliving, a term defined by Professor William E. Halal as ‘a conversational human-machine dialogue that allows a more comfortable and convenient way to shop, work, educate, and conduct most other social relationships.’ I agree with his assessment that people will still crave real social relationships.”

Some define the issues differently; they envision a threat.

Among those expressing concern over the future use of alternate realities is Robert Shaw, an internet strategy and policy adviser for the International Telecommunication Union, who wrote, “This is already the case in immersive gaming environments and virtual reality will be even more addictive. Policy and regulation will move increasingly from physical space into virtual space with analogous rules.” Fredric Litto, a professor at the University of Sao Paulo, wrote, “Good legislation will make it obligatory to identify virtual objects and environments to users so that there can be no confusion between the real and the apparently-real.”

Sean Mead, a technology consultant, wrote, “Simulations will develop to where some players’ experiences so closely mimic reality that the players will be stimulated with the same neurotransmitters that drive feelings of love and pleasure in the real world. There will be simulations as addictive as nicotine and cocaine, but without same degree of societal antipathy.” Consultant Thomas Lenzo agreed, writing, “as the quality of virtual reality increases, it will attract more users and the numbers of cyber-addicts will increase.”

Tiffany Shlain, founder of the Webby Awards, wrote, “I already see many internet junkies who need a fix more than they can be present in the moment.” Denzil Meyers, founder and president of Widgetwonder, expressed concern over a self-selected social stratification, writing, “These technologies allow us to find cohorts which eventually will serve to decrease mass shared values and experiences. More than cultural fragmentation, it will aid a fragmentation of deeper levels of shared reality.”

Technology consultant Robert Eller responded, “A human’s desire to reinvent himself, live out his fantasies, overindulge, addiction will definitely increase. Whole communities/subcultures, which even today are a growing faction, will materialise. We may see a vast blurring of virtual/real reality with many participants living an in-effect secluded lifestyle. Only in the online world will they participate in any form of human interaction. The gin holes of 19th century London or the opium dens of Shanghai are very likely outcomes.”

Nick Carr, an independent writer and consultant, wrote, “I’m not sure if addiction is the right word, but the shift of people’s attention to online information, media, entertainment and communities will erode culture and bring into being a colder if more efficient world.” And Hal Varian, a professor at the UC-Berkeley and consultant for Google, responded, “I think we can see this happening now. The question is whether this is really a bad thing. Personally, I think it is, but I’m not sure I could defend that view philosophically.”

Addiction expert Walter J. Broadbent of The Broadbent Group offered a solution to VR addiction in his response. “I have studied addiction for 36 years. We already have tons of addicts in the world who STERB. That is, they use Short-Term Energy-Releasing Behaviors to feel better. We already have millions who are addicts. The issue is not to regulate them but to offer a life in which such behavior is not needed, and that, too, can be accomplished on the internet. We need to create valuable and helpful communities on the Web that will allow millions to connect.”

Some specifically address concerns toward youth culture.

Ed Lyell, a pioneer in education and the internet who now works at Adams State College, proposes that we take a close look at finding ways to provide guidance to young people as they create their alternate, online personalities. “This is already the new reality for many youth,” he wrote. “Instead of dealing with the challenges and fears of teen identity definition more and more youth are creating multiple ‘virtual’ personalities and losing themselves to each of those game scenarios. Who the ‘actual’ individual becomes or emerges as from such vivid role-playing is unclear to me. Do we end up with much more mature, experientially compassionate people, or even more anxious, fearful, and disassociative personalities? It seems that even minimal intervention at appropriate stages of virtual personality creations could dramatically improve positive over negative long-term outcomes.”

Michael Cann Jr., CEO of Affinio Corporation, responded, “It will be possible for computer users to build ‘alternate realities’ around themselves, and some will find this environment to be so much more appealing and comfortable than the ‘real world’ that they will prefer it. I see a future epidemic, especially among children and teens.” Paul Craven of the U.S. Department of Labor wrote, “Anyone with a teenager can tell you this is already a problem.”

Heath Gibson, competitive intelligence analyst for BigPond in Australia, wrote, “Addiction to chat rooms and online gaming worlds is already emerging as an issue. Recent research has highlighted for example, how teenagers’ ability to learn during school hours is being impacted by a lack of sleep – caused by late-night SMS/chat sessions. There is a real risk that some people will become ‘lost’ to virtual worlds.”

Gordon Bell, senior researcher at Microsoft, assessed the prediction this way: “VR, like email, IM, blogging, gaming, is a new and interesting technology that competes for time and like the others, may become addictive. It will still be up to the individual.”

A number of respondents simply classify VR with books, TV and other communications advances.

Some respondents drew comparisons with earlier communications innovations, including books, television and films. “We will survive to discover new horrors beyond VR,” wrote Paul Saffo. “The history of media is a history of addiction for some, and moral hazard for others. Remember that half a millennium ago, Cervantes’ Don Quixote was driven to windmill-tilting madness because he read too many books. Flaubert’s Emma in ‘Madam Bovary’ got into a jam for the same reason. A century ago, parents lamented that kids were spending too much time inside reading. In mid-century the same fears were transferred to paperbacks, movies and then TV. Now it is videogames and the Web. VR is clearly next, and its seductive hyper-realism will be seductive indeed. But one generation’s outrage is the next generation’s mainstream tool. I will bet that in 2020, parents will be lecturing their children that they can’t go out and play until they finish their VR-based simulation games.”

Douglas Rushkoff, author and teacher, agrees: “As virtual reality gets better, people’s ability to see through it gets better. Novels were the dangerous VR of their own day, just as TV was for us kids, and computer-simulated realities will be for our own kids.”

As worlds converge, how do you define “reality”?

With many going online to participate in IM chat, emails, video conferencing, gaming, shopping, surfing and work, some respondents said it is already difficult to draw a line between what we once called “reality” and the virtual world.

Ted Coopman of the University of Washington wrote, “’Virtual reality’ is a pointless and dated term that has no meaning other than the technical (computer science) definition. We live in a pervasive communication environment and this will only increase. The demarcation of virtual and real and mediated and non-mediated will have no meaning for most people and is an artifact of older generations. Reality will be one seamless world that spans face-to-face and digital areas of action. If anything, the ability to physically take a class or travel to meet with someone will be considered an elite privilege.”

“The real and virtual are converging, and anyway, addiction is a disease for which we will soon find the cure; just a matter of suppressing the expression of a few genes here and there,” wrote Bob Metcalfe, Ethernet inventor, founder of 3Com Corporation, and former CEO of InfoWorld.

Daniel Wang, principal partner with Roadmap Associates, wrote, “While area codes might still define geographic locations in 2020, reality codes may define virtual locations. Multiple personalities will become commonplace, and cyberpsychiatry will proliferate.”

Martin Kwapinski, senior content manager for FirstGov, the U.S. Government’s official Web portal, responded, “The distinction between ‘real’ and ‘virtual’ realities will continue to blur … Our definitions of what is ‘real’ will be tested and changed.” Raul Trejo-Delarbre of Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico wrote, “’Virtual reality’ doesn’t constitute a different reality. It is part of the reality that surrounds us.”

“The internet is becoming increasingly transparent – just as the air is,” argued María Laura Ferreyra, Instituto Universitario Aeronautico. “We will use it all the time as part of our daily life, just as we constantly breathe air. Therefore, we cannot become addicts to internet anymore than we can become addicts to air.”

Charles Hendricksen, a research collaboration architect for Cedar Collaboration, wrote, “For professional communities, ‘virtual reality’ is a meaningless term. Transactions made on the Internet are completely and totally real.”

Clement Chau, of Tufts University’s Developmental Technologies Research Group, responded, “Virtual reality will merge with ‘real reality’ in that some activities will be predominantly virtual, while others will be real. A new term will probably be coined to describe real reality. When this merging of the two realities happens, addiction problems will not be a concern because, a) the novelty wears off, b) virtual reality REQUIRES participation in real reality, and c) virtual reality will become part of the daily lives, as much as the telephone or emails has become part of our everyday routines.”

Patrick O’Sullivan of Illinois State University wrote: “What people refer to as ‘virtual reality’ is still an aspect of all of our reality – it’s not a separate reality any more than books, movies, video games, or our imagination is a separate reality. Saying someone is addicted to virtual reality will one day sound as ridiculous as saying some people today are addicted to books.” And Alex Halavais an assistant professor at Quinnipiac University, responded, “Alternate to what realities? Phone realities? The most recent Pew study seems to belie this: those with stronger virtual social ties have stronger ties generally.”

Defining virtual reality today has to do with defining “presence.”

Thousands of years ago, Roman naturalist Pliny expressed one of the earliest interests in perceptual illusion when he wrote about an artist who had “produced a picture of grapes so dexterously represented that birds began to fly down to eat from the painted vine.”36 Computer graphics and VR scientist Ivan Sutherland wrote in 1965: “The ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter.”37

Most researchers say virtual reality can be defined as a particular type of experience. It goes beyond the “goggles and gloves” systems first emerging in a useable form in the 1990s. Hardware, they say, should not be the focus in defining VR in terms of human experience. The ultimate goals of VR have been defined over time as the amplification of human cognition, perception, and intelligence. They say it has to do with one’s “presence.”

When perception/presence/cognition is not mediated by a communication technology, it reflects only immediate physical surroundings. A mediated environment can be considered an alternate reality or a virtual reality. VR is an experience in an alternate perception. VR researcher Jonathan Steuer of Stanford University has found that different individuals reach this state at different levels in differing ways. He says VR is distinguished from dreams and hallucinations because it requires perceptual input introduced through a communications medium. He also says participation in RPGs, MUDs and online discussion groups can be the construction of a virtual reality in a virtual space.38

As the levels of vividness and interactivity intensify the VR experience in the future, more users are likely to be spending more hours in virtual reality. Steuer warned in a 1995 research article that as VR is perfected it may present dangers: “Rapid advances in both multimedia computer technologies and high-speed data networks hasten the development of a truly global village, in which our ability to interact with friends, family and others who share interests similar to our own will no longer be limited … These new developments are also certain to enhance the possibility of using the media to manipulate and control beliefs and opinions … As an increasing proportion of most individuals’ experiences come via mediated rather than direct sources, the potentially detrimental effects of such manipulation increases exponentially.”

Users are already “migrating” to synthetic online worlds.

VR pioneer Jaron Lanier (the man who coined the term “virtual reality” in 1987) and researcher Frank Biocca predicted in 1992 that the market for VR entertainment would be fairly advanced by 2000, with VR “theaters” in malls, enabling people to watch VR “performances.”39 There are no such elaborate theaters in 2006, although one might argue that productions shown in the best Imax theaters might approximate a feeling of VR. While Mattel introduced the PowerGlove in 1989 (for $89) for use with Nintendo video games, and gamemaker Sega Genesis introduced a headset with VR goggles and earphones in the fall of 1993 for $150, the goggles-and-gloves VR idea has not been mainstreamed. Most “totally-immersive” VR technologies have remained too expensive for use outside major industries such as medicine, the military, and flight-training services.

But millions of people are finding in 2006 that they become so immersed mentally in massively multi-player online role-playing games that they feel themselves to be physically living and moving about in these limited but effective synthetic worlds. They say they are already experiencing VR. This phenomenon is most overwhelmingly in evidence in Korea, where broadband is nearly universally available and where a majority of people spend at least some time most days populating online worlds of one type or another.

In his 2005 book Synthetic Worlds, Edward Castronova wrote that “a virtual reality brought about by games rather than devices” is gaining users at the rate of Moore’s Law (i.e. doubling every two years), and the current number of “hard-core” users numbers at between 10 million and 27 million people. He estimated the commerce conducted between people who spend time in synthetic worlds amounts to at least $30 million annually in the U.S. and $100 million globally, and the collective volume of annual trade within synthetic worlds is above $1 billion.40

The currencies of online worlds have begun to be traded against the dollar, and many of them trade at a higher rate of exchange than real Earth currencies. Some of the most popular of these games in 2006 include World of Warcraft, Second Life, Ultima Online, EverQuest, Lineage, Star Wars Galaxies, Legend of Mir, Eve, There, Mu and Dark Age of Camelot.

Second Life co-founder Philip Rosedale told Wired magazine that the monthly trade in his synthetic world is about $8 million and trending upward, and he added, “I’m not building a game; I’m building a new country.” ICANN member Joi Ito testified in the same issue that he is a World of Warcraft “addict,” adding, “It represents the future of real-time collaborative teams and leadership in an always-on, diversity-intensive, real-time environment – World of Warcraft is a glimpse into our future.”41

In his book, Castronova predicted what he calls the “migration” of more and more people to computer-rendered internet communities and added, “Synthetic worlds are simply intermediate environments: the first settlements in the vast, uncharted territory that lies between humans and their machines … Add immense computing power to a game and … the place that I call ‘game world’ today may develop into much more than a game in the near future. It may become just another place for the mind to be, a new and different Earth … Ensuring that the technology serves such a marvelous end, rather than a less-happy one, is the real challenge for the next few decades. We will be less likely to meet that challenge the longer we treat video games as mere child’s play.” Castronova added, “There is a huge throng of people just waiting at their terminals for a fantasy world to come along, one that is just immersive enough, under the technology they can afford, to induce them to take the plunge and head off into the frontier forever.”42

Researchers warn about “toxic immersion” and other threats.

People are already using synthetic worlds like Second Life to host parties, offer schools, fight wars, exhibit art, conduct business, present theatrical stagings, exhibit political structuring and strife, and experience friendship, sex and marriage. As humans begin to spend many hours in these alternate worlds, they invest time and money, building personal assets. Security in synthetic worlds is a question, just as it is in the “real” online world, and researchers say there is a possibility of “toxic immersion.”

Michael Shapiro and Daniel McDonald of Cornell University wrote in a 1995 research piece, “As the distinction blurs between the physical and computer environments, people will need to make increasingly sophisticated judgments about what is ‘real’ and what is not … we expect that aspect of communication research to become increasingly important as technologies like virtual reality make it possible to both mimic and to modify our perceptual bases of understanding in increasingly complex ways.” They pointed out that whenever a new communications medium evolves and emerges people have a tendency to apply their already-established judgment processes to the new mode of delivery. This often leads to errors and problems (i.e. the 1938 CBS radio theater production of “War of the Worlds” leads to a panic). It takes a period of adjustment for people to become sophisticated in their reception and perception of information delivered in a different way.43

In his book, Castronova predicted three major threats presented by networked VR: 1) a sociopath might create an addictive world; 2) an unethical corporation might build a world that is a threat in some way; 3) an irresponsible government agency might seduce people into an addictive world or regulate other worlds in a way that endangers or causes injury or restrictions to users.44 He warned: “We are unprepared for the emergence of a peer-to-peer world that might expose us to risks that we would rather not face. We can see countless opportunities for research, education and innovation, but only a small cadre of for-profit builders have mastered the craft of building worlds, and there are no training programs that teach it. In view of this general ignorance of synthetic world technology and all it might mean, perhaps the wisest policy of all at this point would be simply to support more research.”45

In 1991, VR pioneer Tom Furness predicted before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Science, Space and Technology that “televirtuality promises to subsume the existing media of communications.” He explained that both humans and computers are growing more intelligent and as they do so they are collapsing their differences and merging.46

In responding to the 2006 survey scenario, Marilyn Cade, a technology consultant and policy expert, wrote, “We should acknowledge and embrace this as a challenge and look for solutions and remedies, and safeguards … We should not deny the value of the advances of technology because of the harm; we should embrace the technology and study and seek to provide any appropriate awareness and safeguards, harnessing technology/and managing it effectively. To benefit, and not to harm humankind is the next frontier, isn’t it?”