As of Monday night, more than 100 million Americans had cast their ballots in the 2020 general election – by mailing them in, dropping them off or going to a designated early-voting location. That record number, already about three-quarters of the total ballots cast in 2016, all but guarantees that, for the first time, fewer than half of all votes will be cast on Election Day itself.

Much of that is due to the COVID-19 pandemic and how states have responded to it. Most states, fearful that long lines of voters could turn Election Day into a major “superspreader” event, have made it easier to vote elsewhere and at other times by expanding mail balloting and early in-person voting.

But votes cast on Election Day have grown steadily less significant over the past several election cycles as a share of total votes cast, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of two datasets.

Among its many impacts, the coronavirus pandemic has upended the tradition of going to the polls on Election Day. But even before this year, more Americans have chosen the options of voting early and using mail or absentee ballots.

To explore this trend, we analyzed the U.S. Census Bureau’s biennial supplement to the Current Population Survey on voting and registration, which includes data on overall self-reported turnout and method of voting by age, sex, race, Hispanic origin and other demographic categories. We also used data available in the Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS) Comprehensive Report, a biennial analysis of state-by-state data that covers various topics related to the administration of federal elections. Data on this fall’s early vote came from the United States Elections Project, headed by University of Florida political science professor Michael McDonald.

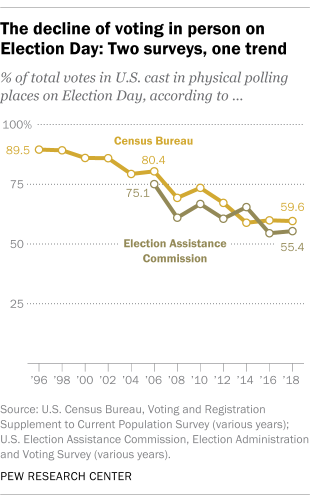

In 1996, 89.5% of voters reported voting in person on Election Day, according to the Census Bureau’s post-election surveys. As recently as 2006, that share was 80.4%. But then the in-person Election Day portion of the vote began to skid, falling to below 60% each election cycle since 2014.

The trend also is evident in the biennial Election Administration and Voting Survey (EAVS), conducted by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, a federal agency charged with helping states meet federal election rules. The survey, which gathers voting, registration and election-administration data from state and local officials, found that the share of votes cast at physical polling places on Election Day fell from 75.1% in 2006 to 55.4% in 2018.

Another way of tracking the erosion of Election Day voting: In 2010, votes cast on Election Day accounted for a majority of all votes in 42 states and the District of Columbia, according to that year’s EAVS. In 2018, that was true in just 34 states and D.C.

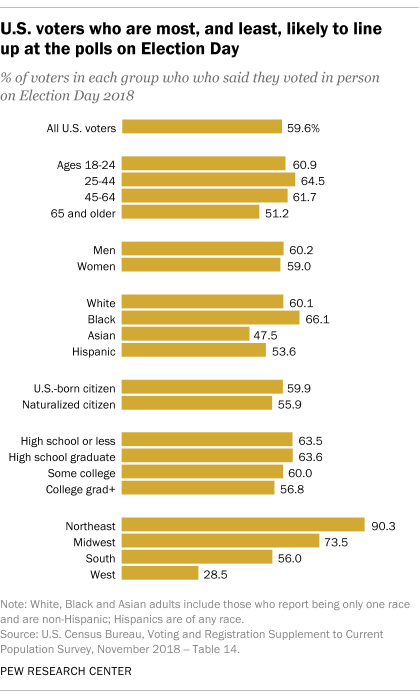

Historically, and perhaps counterintuitively, older voters have been the least likely to vote in person on Election Day, according to Census Bureau estimates. In 2018, for instance, 51.2% of voters ages 65 and older said they had cast their ballot in person, compared with 59.6% of all reported voters. The likeliest group to have queued up outside a school, firehouse or other polling place was 25- to 44-year-olds, 64.5% of whom cast their ballots in person on Election Day.

The main alternatives to casting a ballot in person on Election Day are voting in person during a designated early-voting period and voting by absentee or mail ballot (which typically can be either mailed back or dropped off at a secure location). Early in-person voting was relatively uncommon until fairly recently. In 1992, only three states had formal early-voting periods, but the number rose steadily throughout the 1990s and 2000s. By 2016, 22 states offered early voting.

Until this year, early in-person voting has tended to be most common in the South and West. In 2018, for instance, two-thirds of all Texas votes were cast in person before Election Day. But this year, under pandemic pressure, more states have jumped on board, with 41 states and the District of Columbia offering some form of organized early voting.

Mail voting, also called absentee voting, has been a feature of U.S. elections since the Civil War, and every state offers some form of it. Once limited to those who physically could not go to their precinct polling place on Election Day, mail voting accounted for roughly a quarter of all votes cast in the 2018 federal elections, the Census Bureau has found.

In five states – Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah and Washington – mail ballots are now the default method of voting for all elections. Four other states (California, Nevada, New Jersey and Vermont) and the District of Columbia have joined them for this year’s election, sending ballots to all registered voters. Many other states have changed their laws this year to expand access to mail voting. The result so far is that voters have returned more than 65 million mail ballots, nearly twice as many as were cast in all of 2016.