Americans’ levels of social trust are linked to the emotions they are experiencing during the coronavirus outbreak and their judgments about how different groups are responding to the pandemic, according to a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults conducted March 19-24.

Other factors are at play, too. Recent Center reports have shown that older people, white adults and those with higher household incomes or more education are more likely than others to have had less negative emotional reactions to the outbreak, and they are judging the performance of others more positively. Those earlier reports can be found here, here, here, here and here.

How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted this study as part of its continuing exploration of people’s trust in each other and in the country’s institutions and to understand how the new coronavirus outbreak has affected this. For this analysis, we surveyed 11,537 U.S. adults from March 19-24, 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling). This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

The questions used to measure the levels of psychological distress were developed with the help of the COVID-19 and mental health measurement group from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (JHSPH): M. Daniele Fallin (Johns Hopkins School of Public Health), Calliope Holingue (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH), Renee Johnson (JHSPH), Luke Kalb (Kennedy Krieger Institute, JHSPH), Frauke Kreuter (University of Maryland, University of Mannheim), Elizabeth Stuart (JHSPH), Johannes Thrul (JHSPH) and Cindy Veldhuis (Columbia University).

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

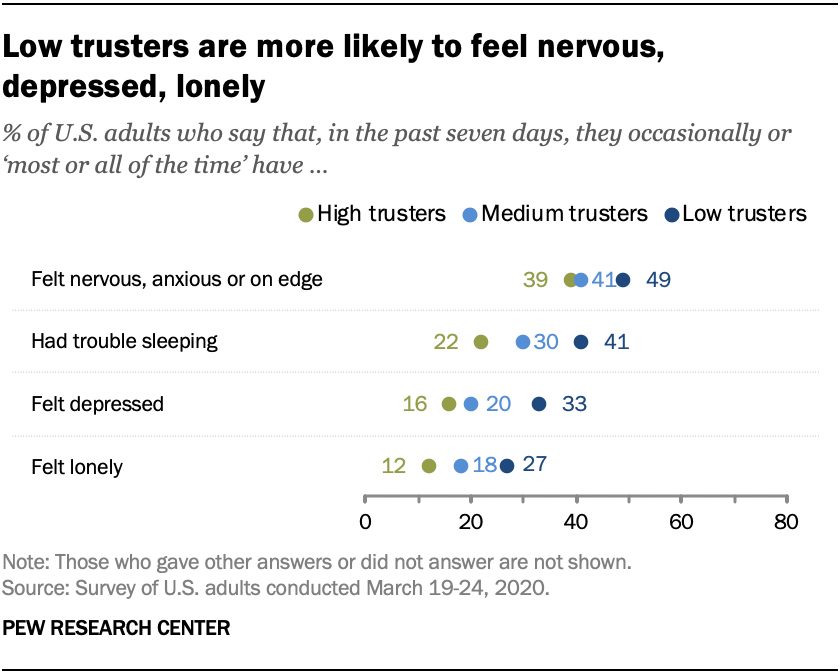

The three-part classification system shows that the less interpersonal trust people have, the more frequently they experience bouts of anxiety, depression and loneliness.

Those with lower trust also report more frequent struggles with sleeping and fewer moments of hope. Additionally, “low trusters” are less likely to feel positively about how ordinary people in their communities are reacting to the crisis, according to the survey of 11,537 adults who are members of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel.

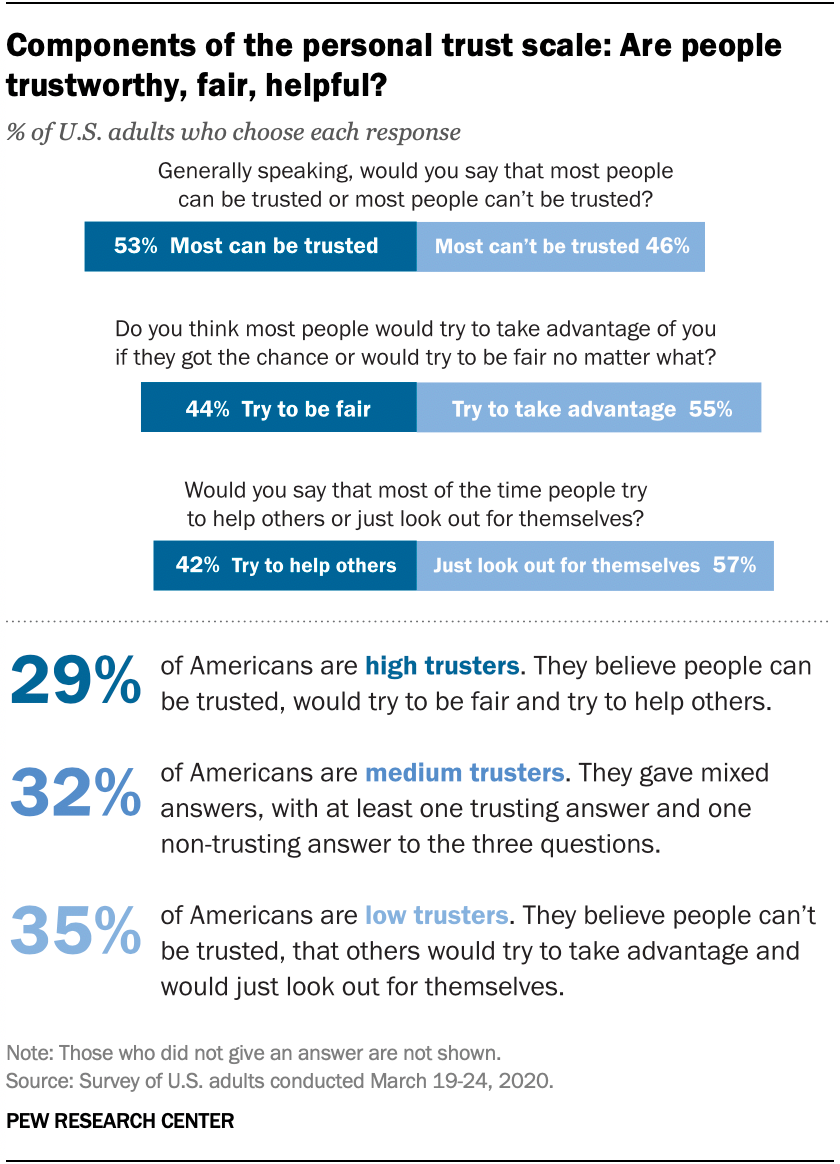

This analysis updates research the Center did in 2018 about trust and distrust in America. As part of that effort, the Center divided American adults into the three trust categories based on their responses to questions about others. Those who answered all three questions with trustful answers were slotted as high trusters; those who answered all three with non-trust answers were categorized as low trusters. And those who gave mixed answers to the three questions, with at least one trusting answer and one non-trusting answer, were listed as medium trusters.

The new mid-March survey in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis shows there has been a modest but statistically noticeable improvement in people’s views about others’ altruism. In 2018, 37% of Americans believed that most of the time people will try to help others. The new survey shows that share has increased to 42%. A majority (57%) still believes most of the time people would just look out for themselves, but that is a slight drop from 62% who agreed with that statement in the 2018 poll.

These changes since 2018 and small shifts in people’s responses to the other questions reshuffle the trust landscape of Americans a bit. The share of adults who are “high trusters” has risen from 22% in 2018 to 29% now, and the share of “medium trusters” has fallen from 41% then to 32% now. The number of low trusters remains steady (35%).

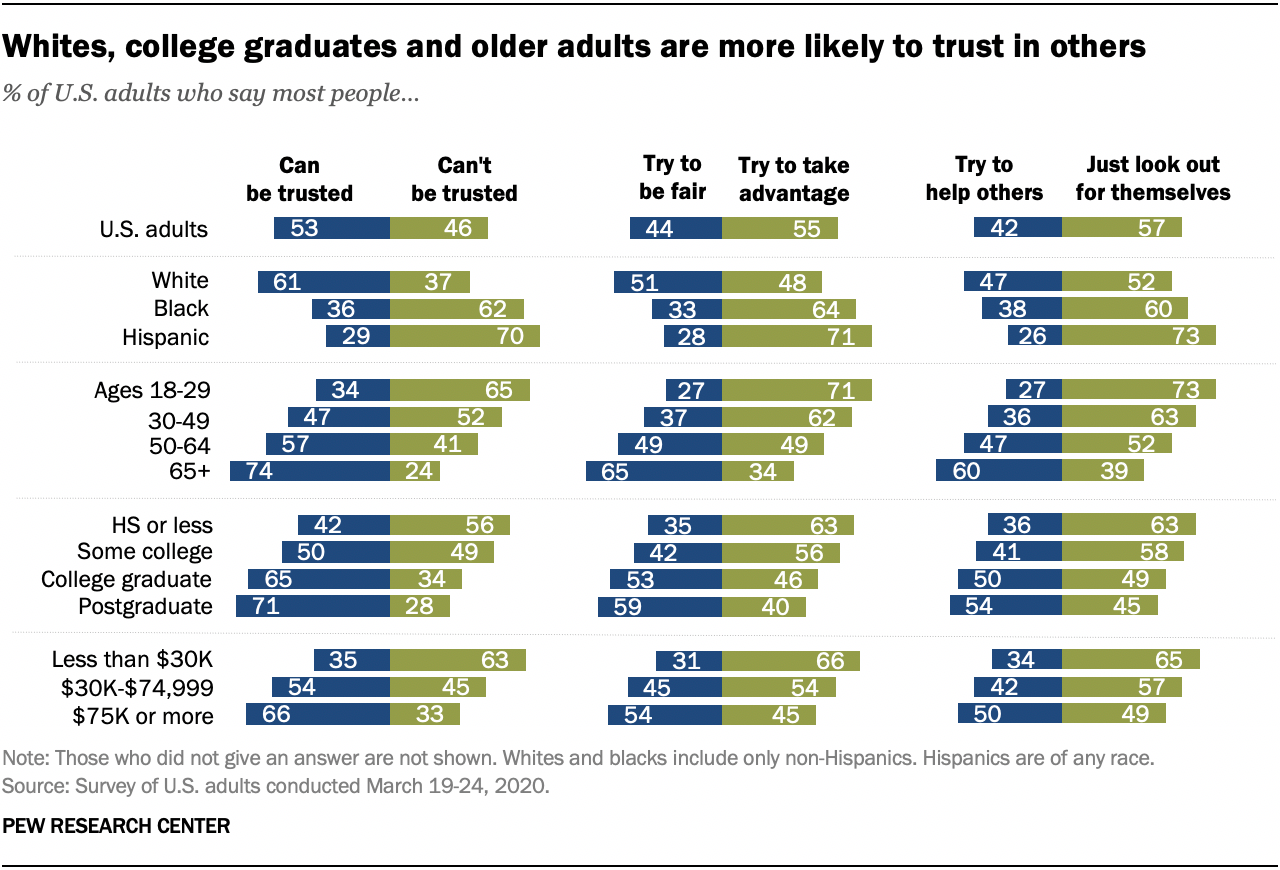

A number of personal characteristics play a role in people’s levels of social trust. Older people, whites and those with higher household incomes or higher levels of education are more likely than others to give trusting answers. These patterns mirror those found in 2018. Statistical modeling shows that people’s overall level of social trust is an independent predictor, above and beyond preexisting demographic differences, of how they are reacting to the pandemic.

While the association between social trust and personal emotions is striking, it is important to note that there is no way to be certain whether variations in people’s emotions are reactions to the COVID-19 outbreak or if they primarily reflect underlying differences between people that already existed. The answer may be both.

To better understand Americans’ emotions and feelings during the pandemic, the March 19-24 survey asked people to describe how frequently in the most recent seven days they had felt “nervous, anxious or on edge,” depressed, lonely, or hopeful, as well as whether they had had trouble sleeping. The answer options were: “rarely or none of the time (less than one day)” out of the past seven days; “some or a little of the time (1-2 days)”; “occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3-4 days)”; or “most or all of the time (5-7 days).”

Some 49% of low trusters say they occasionally or more often have felt nervous, anxious or on edge in the past seven days, compared with 39% of high trusters and 41% of medium trusters. Additionally, low trusters are roughly twice as likely as high trusters to report that they have had frequent trouble sleeping (41% vs. 22%) or have experienced feelings of depression (33% vs. 16%) at least occasionally during this time. A quarter of low trusters (27%) say they have somewhat frequently or more often felt lonely, in contrast to 12% of high trusters who have felt lonely at that rate during the past seven days. Finally, six-in-ten low trusters (59%) say they have rarely or only some of the time felt hopeful, compared with 39% of high trusters who have felt hope that rarely.

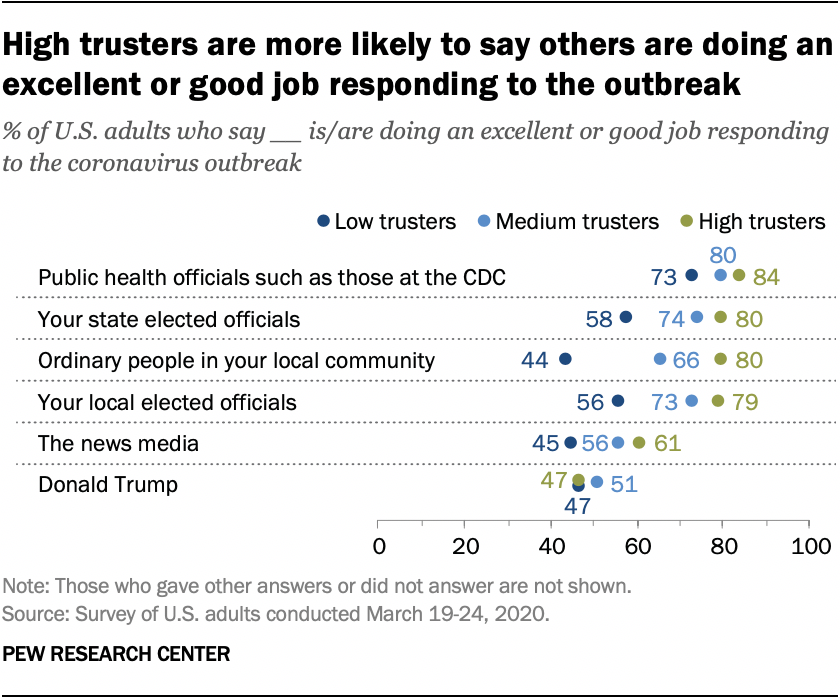

When it comes to the way Americans view the behavior of various groups in the crisis, low and high trusters have strikingly divergent opinions, starting with the way they feel ordinary people are responding to the outbreak. Fully 80% of high trusters think ordinary people in their own communities are doing an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak, compared with 44% of low trusters who feel that way.

There are also differences among the trust groups when it comes to their judgments about the job the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is doing: 84% of high trusters rate the job as excellent or good, contrasted with 73% of low trusters. There are even wider gaps when the question is how state and local elected officials and the news media are performing in the crisis. The only place in this survey where low and high trusters are similar is on their thinking about President Donald Trump’s performance in handling the crisis: Just under half (47%) of both groups say they think he is doing an excellent or good job.

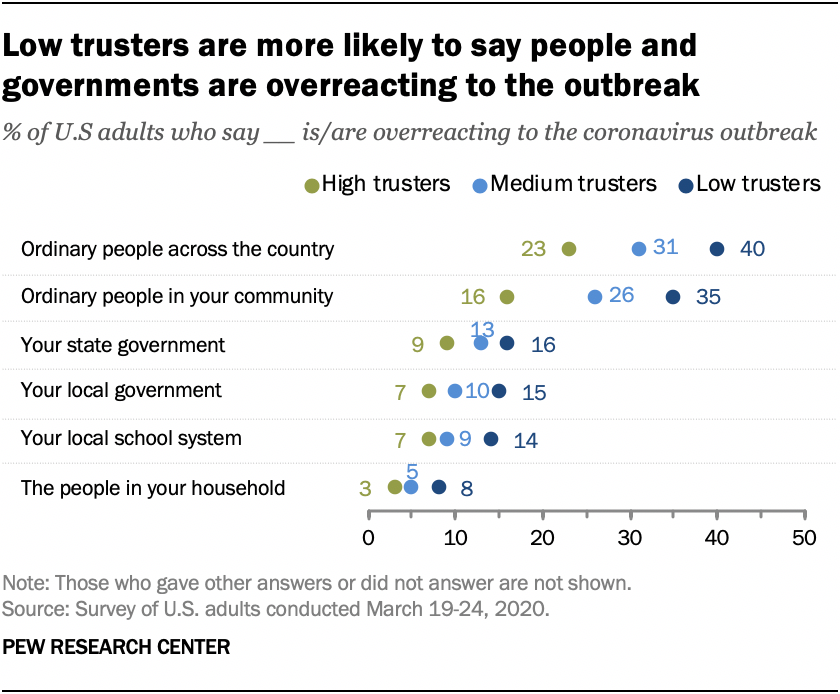

In another series of questions seeking people’s assessments in the middle of March of how different groups are responding to the crisis, low trusters are the most likely to believe that others are overreacting. Four-in-ten low trusters (40%) believe other Americans across the country are overreacting to the crisis and 35% think ordinary people in their communities are likewise overreacting. For high trusters, those figures are 23% and 16%, respectively. Low trusters are also more likely to believe that state and local government elected officials and local school systems are overreacting. Still, the overall picture among all the trust groups is that state and local officials and school systems are reacting “about right” to the pandemic.

Here are some other findings related to interpersonal trust and how it is tied to people’s experiences, behaviors and attitudes about the COVID-19 outbreak:

- High trusters are more likely than other groups to believe the coronavirus outbreak is a significant crisis: 72% of high trusters believe that, compared with 67% of medium trusters and 63% of low trusters. Moreover, high trusters are more likely to say their personal life has changed in a major way as a result of the crisis: 48% say that versus 41% of low trusters.

- Yet, high trusters are less likely than low trusters to think that the coronavirus poses a major threat to their personal finances (40% vs. 58%) and to their personal health (32% vs. 40%). This may in part be a function of the fact that high trusters are more likely to be better off financially than low trusters.

- Low trusters are more likely than high trusters to say they are not too or not at all confident that local hospitals and medical centers will be able to handle the medical needs of people who are seriously ill during the coronavirus outbreak (34% vs. 25%).

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.