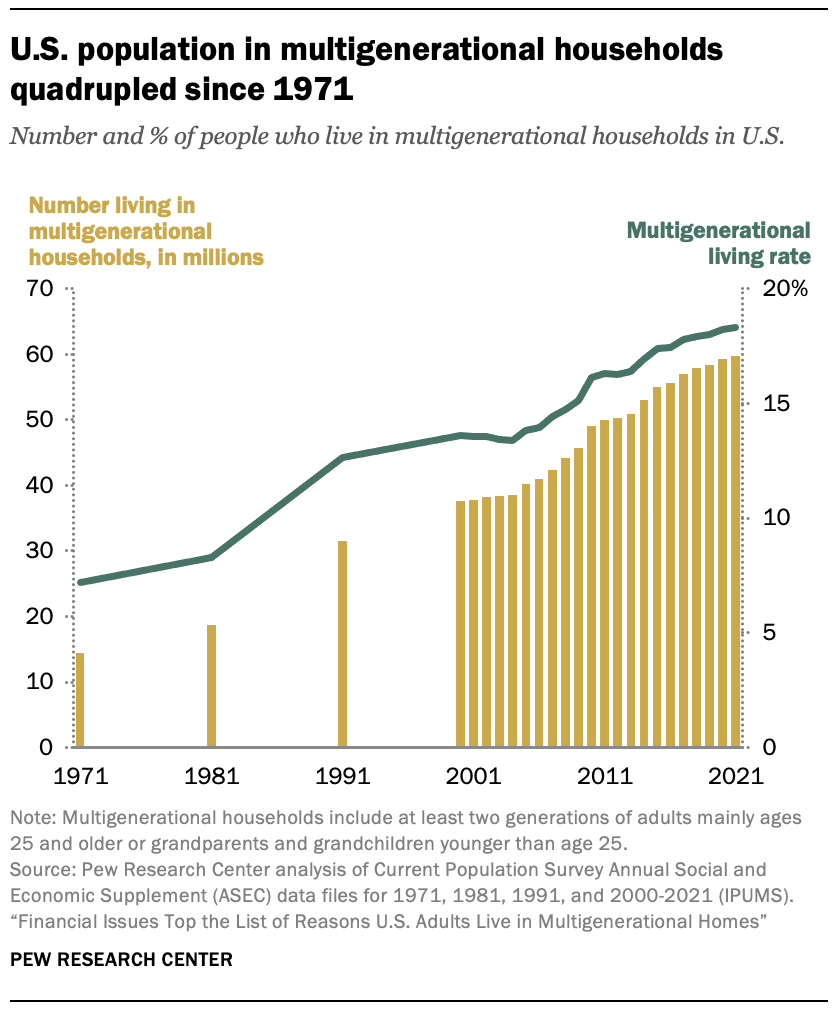

The number of Americans who live in multigenerational family households is about four times larger than it was in the 1970s, while the number in other types of homes grew by far less. The share of the U.S. population living in multigenerational homes more than doubled over the past five decades.

In March 2021, there were 59.7 million U.S. residents who lived with multiple generations under one roof, compared with 58.4 million in 2019, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of census data. The share of the U.S. population living in multigenerational households in 2021 was 18%.

After declining in earlier decades, multigenerational living has grown steadily in the U.S. since the 1970s. From 1971 to 2021, the number of people living in multigenerational households quadrupled, while the number in other types of living situations is less than double what it was. The share of the U.S. population in multigenerational homes has more than doubled, from 7% in 1971 to 18% in 2021.

Multigenerational living is growing in part because groups that account for most recent overall population growth in the U.S., including foreign-born, Asian2, Black and Hispanic Americans, are more likely to live with multiple generations under one roof. Thus, the rise in the multigenerational family household population is linked to the changing makeup of the overall U.S. population. However, multigenerational living also is rising among non-Hispanic White Americans, who accounted for a higher share of the multigenerational household population growth from 2000 to 2021 (28%) than of total population growth (9%).

Multigenerational households are defined as including two or more adult generations (with adults mainly ages 25 or older) or a “skipped generation,” which consists of grandparents and their grandchildren younger than 25. Most consist of at least two adult generations – for example, young adults living with their parents, parents residing in their adult children’s homes, or a grandparent, adult child and adult grandchild under one roof. About 5% of multigenerational households consist of grandparents and grandchildren younger than 25.

The numbers for this analysis come from the Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, which reports data for the civilian population except those living in institutions such as prisons or mental hospitals. The trends and patterns here are similar to previous Pew Research Center reports based on the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, although the Current Population Survey numbers tend to be lower. See Methodology for more detail.

Who lives in multigenerational households?

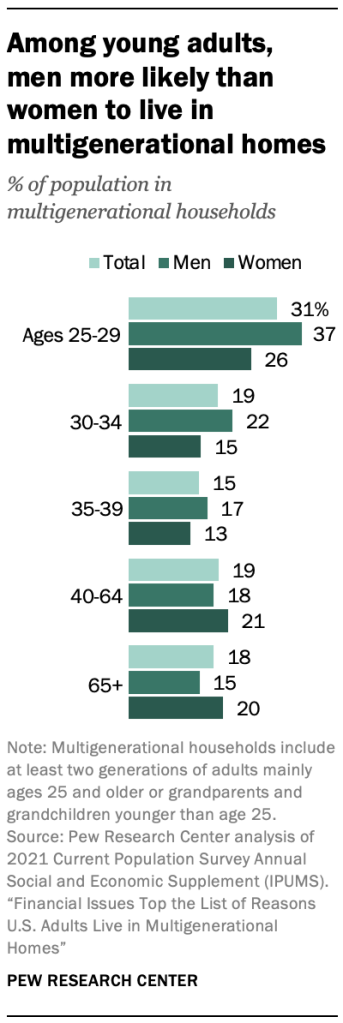

The likelihood of living in a multigenerational household varies notably by age, race, and nativity, and there are differences by geographic location as well. Among the greatest variations is gender disparity among young adults, the age group most likely to live in multigenerational homes.

Men and women overall are equally likely to live in multigenerational households, but men are more likely to do so among those younger than 40 and women are more likely to do so among those ages 40 and older. For example, among the 25- to 29-year-old group, young men (37%) are notably more likely to be in a multigenerational living arrangement than young women (26%). Among a broader age group of young adults than in this report – 18- to 34-year-olds – living with parents has been the dominant living arrangement for young men for more than a decade.

But among the oldest Americans – ages 65 and up – 20% of women live in multigenerational households, compared with 15% of men. Older Americans are less likely to live alone than they were several decades ago, a change linked to the growing share of older women who live with their spouse or children.

By broad age group, Americans ages 25 to 39 and those ages 55 to 64 are about equally likely to live in multigenerational family households (each 22%). But within the younger group, those ages 25 to 29 (31%) are far more likely to live with multiple generations under one roof than those ages 30 to 34 (19%) or 35 to 39 (15%). Previous analysis has found that today’s young adults are more likely to be living in their parents’ home (and for longer stretches) than previous generations, and this is especially prevalent among those with a high school education compared with those with a bachelor’s degree or more education.

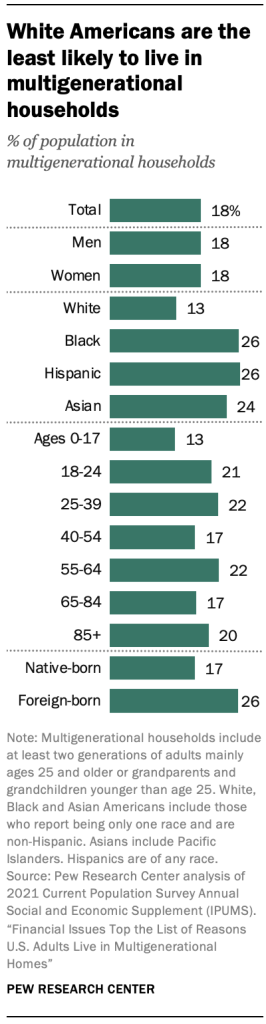

Among major racial and ethnic groups, Americans who are Asian, Black or Hispanic are more likely than those who are White to live in a multigenerational family household.

About a quarter of Asian (24%), Black (26%) and Hispanic (26%) Americans lived in multigenerational households in 2021, compared with 13% of those who are White.

Immigrant status also is linked to the likelihood of multigenerational living. A higher share of foreign-born Americans (26%) than U.S.-born Americans (17%) live in a multigenerational family home. The greater propensity of immigrants to live in multigenerational households is true even after factoring in the racial and ethnic makeup of foreign-born Americans, who are less likely than the U.S. born to be non-Hispanic White.

Geography also factors into how likely people are to live in multigenerational homes. Americans living in Western states (21%) are more likely than those in the Midwest (14%), South (19%) or Northeast (19%) to reside with multiple generations under one roof. Those in the Midwest are less likely than those in other regions to be in multigenerational arrangements. Americans in metropolitan areas (19%) are somewhat more likely than those in rural communities (16%) to live in multigenerational family homes.

Drivers of growth in multigenerational households

Both the share and number of Americans living in multigenerational households have risen steadily since 1971, when this group numbered 14.5 million compared with 2021’s 59.7 million. Growth accelerated during the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and has continued at a slower pace since then, but there is no sign that the multigenerational household population total has peaked.

The slackened growth of the multigenerational household population echoes broader sluggish trends. U.S. population growth from 2010-2020 was the smallest for any decade since the 1930s, and growth in the number of households was at the lowest pace in U.S. history. The number of new immigrants, already slowing in recent years, slumped during the pandemic.

Since 2000, the multigenerational household population has grown by 22.1 million people, but some groups played a larger role than others in driving that change. Americans younger than 40 accounted for almost half (49%) of the increase in the multigenerational household population but only 17% of overall population growth. In general, young adults are marrying later and staying in school longer than previous generations, which may contribute to their rising inclination to live with other family members under one roof.

Americans in multigenerational households less likely to live in poverty

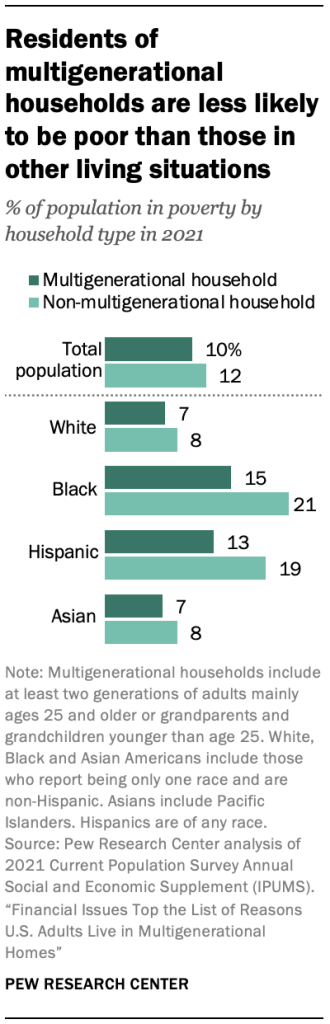

Multigenerational households can have financial advantages. Pooling financial resources means that family helps out in hard times. Some of these households have more earners than non-multigenerational arrangements, providing a safety net if one person loses a job. However, multigenerational households are larger than other types, so any money brought in may need to cover more people.

Living in a multigenerational household appears to offer protection against falling into poverty, according to census data. Poverty levels are lower for Americans living in multigenerational households (10%) than other types of households (12%). In 2021 data, the share of people in poverty during the previous year was lower in multigenerational households for White, Black and Hispanic Americans.

The sharpest difference was for adults ages 85 and older. Among this group, 8% in multigenerational households lived in poverty, compared with 13% of those in other types of homes. (The data source does not include elderly living in nursing homes.)

Groups that are more economically vulnerable had even more benefit from living in multigenerational households. For those who are Hispanic, 13% of those in multigenerational households lived in poverty, compared with 19% of those in other living situations. For Black Americans, the difference was 15% in multigenerational homes compared with 21% in other households. For those who are White, who as a group have higher median household incomes, the advantages were more modest.

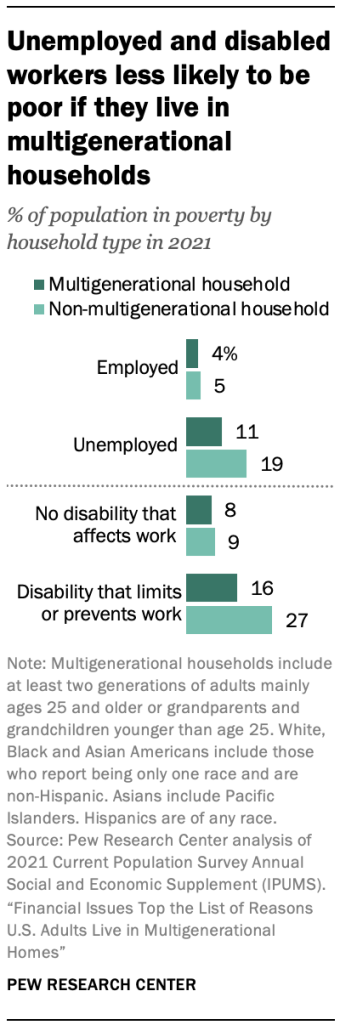

Among the unemployed, 11% of those living in multigenerational households were below the poverty line, compared with 19% of those in other living arrangements. Unemployed Americans were more likely than others to live in multigenerational households (28% did in 2021 vs. 18% of those who are employed).

Those with a disability that limits or prevents them from working, another group of Americansat risk of poverty, also appear to benefit from being in a multigenerational household. This group is more likely to live in a multigenerational home than people without a work disability (24% compared with 19%). Those with a work disability who live in a multigenerational household are less likely to be poor (16%) than their counterparts who live in another type of home (27%).

The current analysis did not include household income data, but a previous analysis found that median adjusted household income was slightly lower in multigenerational households than other types. However, the reverse was true for homes headed by Black, Hispanic, and foreign-born householders: Incomes were higher in multigenerational homes for those groups. Even multigenerational households with unemployed residents had higher adjusted median incomes than other types of households where unemployed residents lived.