For Americans, the sight of Greeks lined up outside shuttered banks evokes images from the Great Depression – the last time all banks in the U.S. were closed on government orders. In fact, while banking crises are depressingly common around the world, governments typically only impose such “bank holidays” as a last resort, to keep funds from fleeing the banking system and sending it crashing down.

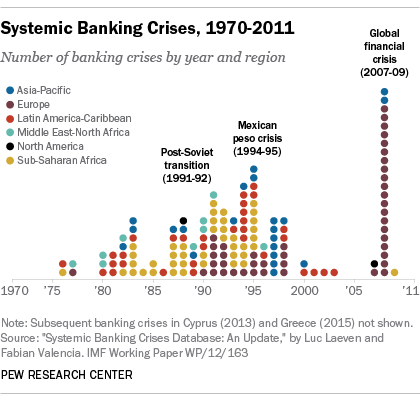

We examined a comprehensive database of financial crises from 1970 through 2012 compiled and maintained by two economists for the International Monetary Fund to see just how unusual the current situation in Greece is. The IMF economists defined “systemic banking crises” as those with both “significant signs of financial distress in the banking system,” such as major bank runs, losses and liquidations, and significant policy interventions in response, such as deposit guarantees, nationalizations, recapitalizations, deposit freezes and bank holidays.

Of the 147 banking crises listed, in only seven cases did national governments freeze deposits and/or order bank holidays. Most of those cases were in Latin America: Argentina (in 1989 and again in 2001-02), Brazil (1990), Ecuador (1999), Panama (1988) and Uruguay (2002). In Africa, there was Chad (1983). The most recent major incident occurred in 2013 in Cyprus, as part of a bailout deal with the European Union and the IMF.

In the past, bank holidays usually lasted a week or less, according to the database. However, Cypriot banks were closed for two weeks in 2013, and Greek banks have been shut since June 28.

History shows that even after the shuttered banks reopen, restrictions on accessing deposits and transferring funds – especially those held by foreigners or denominated in foreign currency – can last for months or even years. Uruguay, for example, restructured $2.2 billion in dollar-denominated time deposits, stretching out their maturities over a three-year period. This past April, Cyprus lifted the last of the capital controls imposed in 2013.

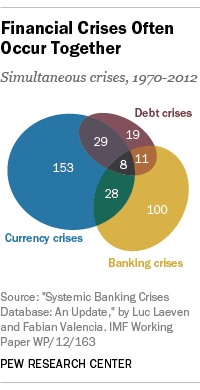

The IMF researchers found that nearly a third (32%) of banking crises since the 1970s were accompanied by sovereign-debt crises (i.e., a government being unable or unwilling to repay its bondholders), currency crises (when the nation’s currency rapidly loses value), or both. Greece’s banking crisis, in fact, began in 2009-10 as a debt crisis. To keep the Greek government from defaulting on massive bank loans it had taken out before the global financial crisis, the European Commission, European Central Bank and IMF agreed to two bailout loans totaling more than 240 billion euros in exchange for a series of austerity measures.

Greece was supposed to repay 1.55 billion euros ($1.73 billion) to the IMF last month, but instead became the first developed nation ever to miss an IMF payment. The country has 29.15 billion euros (nearly $32 billion) in debt coming due in the next three years, including a repayment of 3.5 billion euros ($3.8 billion) to the European Central Bank on July 20.

Failure to reach agreement on a third bailout package could result in Greece’s abandoning the euro entirely in favor of a new national currency, which analysts generally expect would rapidly lose value relative to the euro. That would mean Greece could face simultaneous banking, debt and currency crises – something that’s happened fewer than a dozen times since 1970, according to the database.