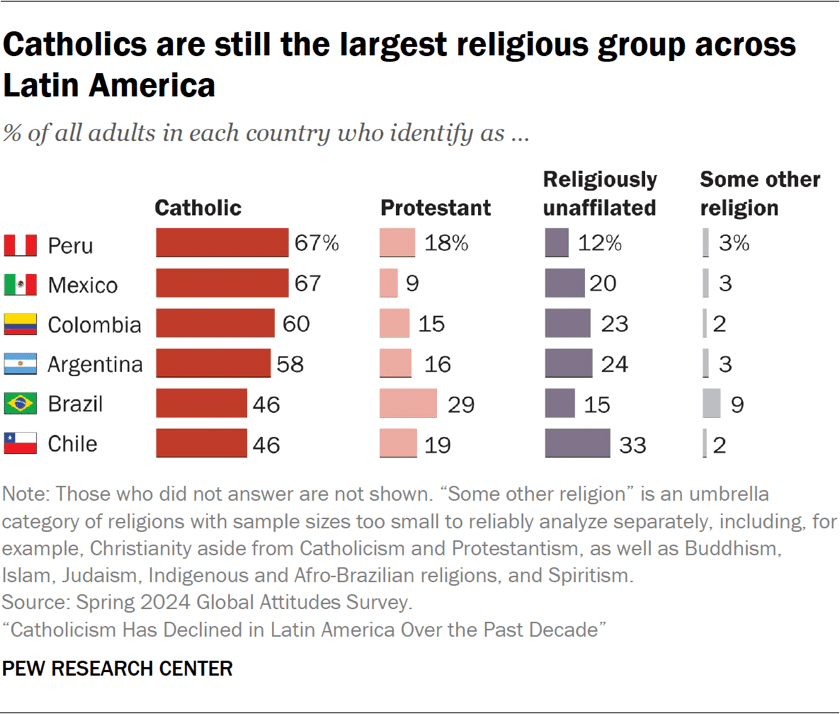

Catholics continue to be the largest religious group in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru – despite declining as a share of these countries’ adult populations over the past decade. Today, Catholics make up between 46% and 67% of adults in the six Latin American countries surveyed.4

Religiously unaffiliated adults are the second-largest group in four of the countries: Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Mexico. (The religiously unaffiliated population, sometimes called religious “nones,” is comprised of people who answer a question about their religion by saying they are atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.”)

In Brazil and Peru, Protestants are the second-largest group. Pew Research Center’s 2024 survey of six Latin American countries also finds that:

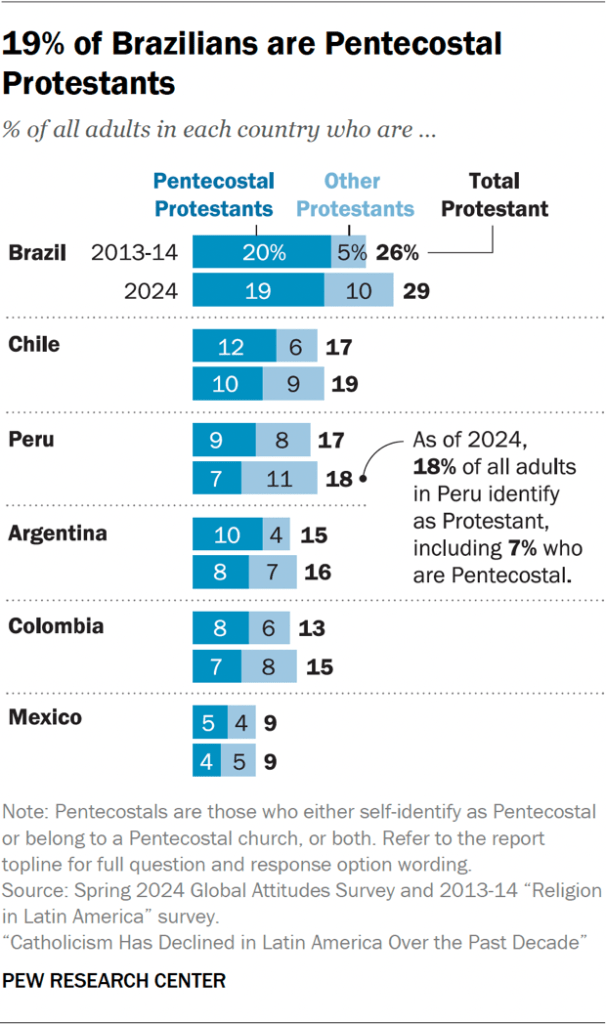

- One-in-five or fewer adults in each country are Pentecostal Protestants.

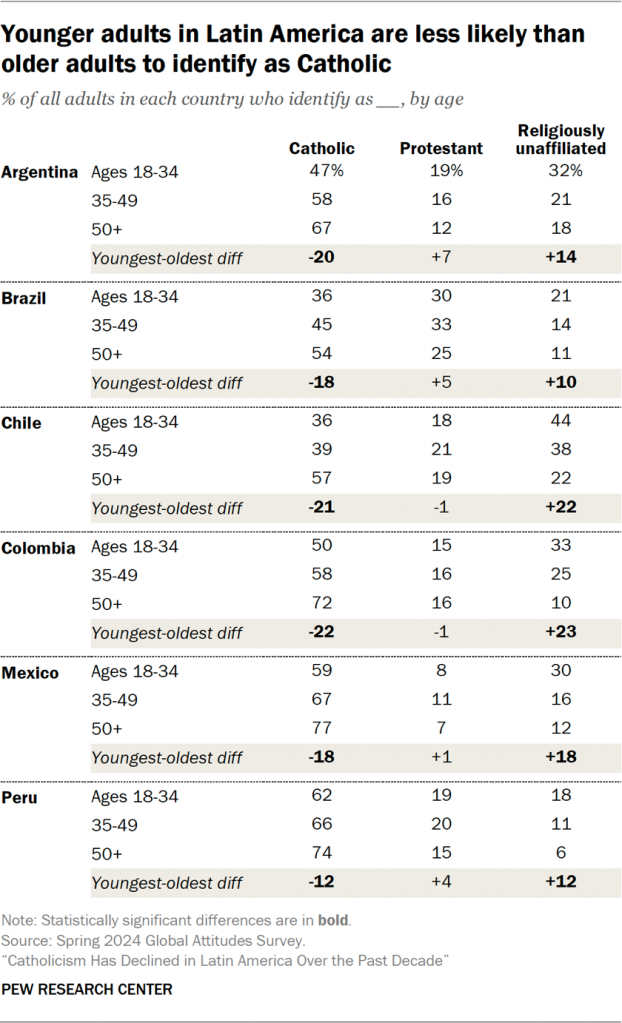

- Religious identity differs by age and education. For example, younger adults are less likely than older adults to identify as Catholic and more likely to be “nones.”

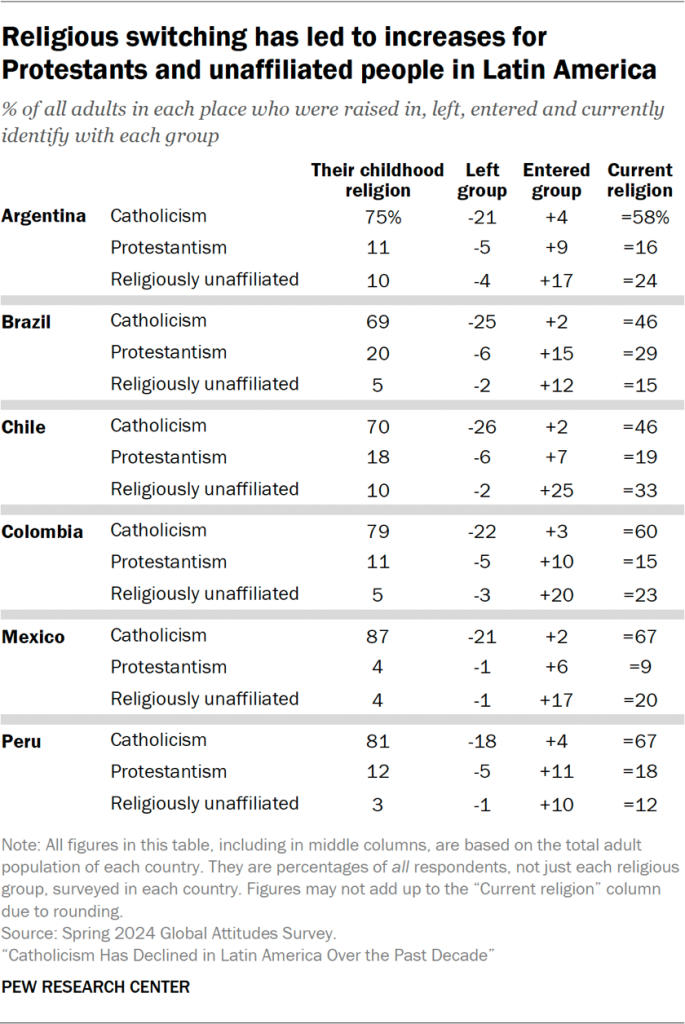

- Religious switching – changing from one’s childhood religion to a different religious identity in adulthood – has led to a net loss for Catholics in every country surveyed, but to net gains for the religiously unaffiliated and Protestants.

- Catholics who have left their religion are now mostly Protestants or religiously unaffiliated, while former Protestants tend to have become religiously unaffiliated.

Religious composition of each country

Majorities of adults in Mexico (67%), Peru (67%), Colombia (60%) and Argentina (58%) identify as Catholic. In Brazil and Chile, 46% of adults are Catholic.

Protestants make up smaller shares of the adult population in Latin America, ranging from 9% in Mexico to 29% in Brazil.

Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Mexico have larger shares of religiously unaffiliated people than of Protestants. For instance, 33% of Chilean adults identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” while 19% identify as Protestant.

Pentecostalism

Pew Research Center estimated the share of Pentecostals in this survey using two questions. We asked all Christians whether they describe themselves as Pentecostal, or not.5 We also asked all Protestants what kind of church they belong to, with one option being “a Pentecostal church, for example, Assemblies of God or the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God.”6 If respondents who identified as Protestant said “yes” to the first question (they consider themselves Pentecostal), or they indicated they belong to a Pentecostal church in the second question – or both – they were categorized as Pentecostal.

As of 2024, Pentecostal Protestants make up small percentages of the overall populations in the six countries surveyed, ranging from 4% of all adults in Mexico to 19% in Brazil. This group’s relative size has remained fairly stable in the broader landscape since 2013-14.

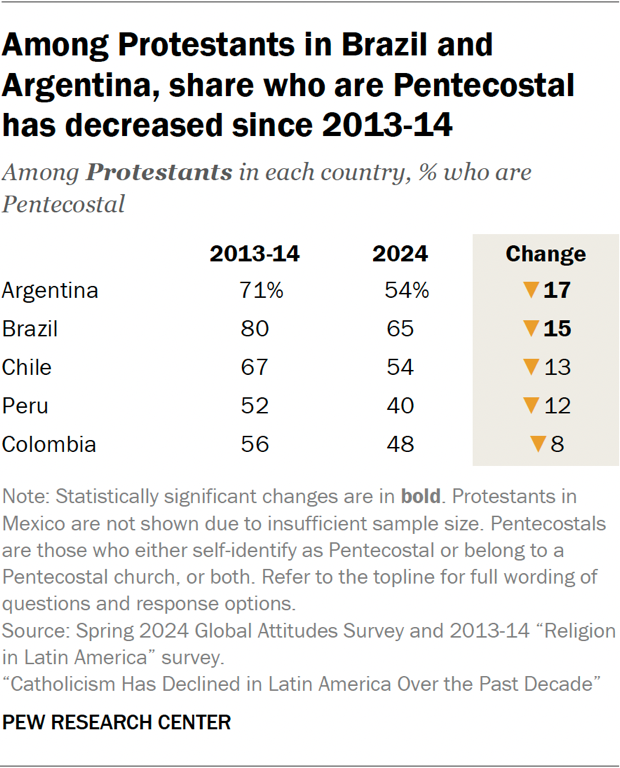

Yet, over the past decade, Pentecostalism appears to have lost some ground within Protestantism.

In 2013-14, majorities of Protestant adults in several of the six countries surveyed were Pentecostal. For instance, 71% of Argentine Protestants identified as Pentecostal in 2013-14.

Today, Brazil is the only Latin American country surveyed where a majority of Protestants are Pentecostal (65%).7

While the decline in the share of Protestants who are Pentecostal is statistically significant in two countries (Argentina and Brazil), the sample sizes of Protestants are relatively small, so there are large margins of error 8

How religious identity differs by age, gender and education

In all six Latin American countries surveyed, younger adults are much less likely than older adults to identify as Catholic. For example, 59% of Mexican adults ages 18 to 34 say they are Catholic, compared with 77% of Mexicans ages 50 and older.

Younger adults are more likely than older adults to identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.” For instance, 33% of Colombian adults under 35 say they are religiously unaffiliated, compared with 10% of Colombians 50 and older.

There are no significant differences by age in the shares of adults who identify as Protestant in each country, or who identify as Pentecostal Protestants.

In general, there are no significant differences in the shares of Latin American men and women who identify as Catholic, Protestant or religiously unaffiliated.

In Argentina, Chile and Peru, people with more education are less likely to be Protestant. Just 12% of Argentine adults with higher levels of education (i.e., those who have completed secondary school) are Protestant, versus 20% of Argentines with lower levels of education.9

By the same token, adults with higher levels of education are more likely than those with lower levels to be religiously unaffiliated in five of the six countries. In Argentina, 28% of adults with more education are “nones,” compared with 18% of Argentines who have less education.

There are no differences by education level in the shares of adults who identify as Catholic in any of the countries surveyed.

(Refer to the detailed tables for more information about how religious affiliation varies by frequency of prayer and across demographic groups.)

Religious switching

Change in a country’s religious landscape is a result of many factors, including people moving from one religion to another, or from one religion to no religion. The analysis of “religious switching” in this report focuses on the change between the religious group in which a person says they were raised (during their childhood) and their religious identity now (in adulthood).10

Across the six Latin American countries surveyed, more people have left Catholicism since childhood than joined. As a result, Catholicism has experienced an overall (or “net”) loss of adherents due to religious switching.

In Chile, for instance, more people have left Catholicism (26% of all Chilean adults) than have entered the faith (2%), a net loss for Catholics that is equivalent to 24% of Chile’s total adult population.

On the flip side, Protestants and the religiously unaffiliated have experienced a net gain in most Latin American countries surveyed because of religious switching.

For example, in Brazil, 6% of all adults say they were raised Protestant but no longer identify as such, while 15% of all Brazilian adults say they were not raised Protestant but are now Protestants.

Similarly, the religiously unaffiliated category has grown because of religious switching: 4% of Mexican adults say they were raised atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” compared with 20% who are religiously unaffiliated today.

Related: Around the World, Many People Are Leaving Their Childhood Religions

How do former Catholics and Protestants identify now?

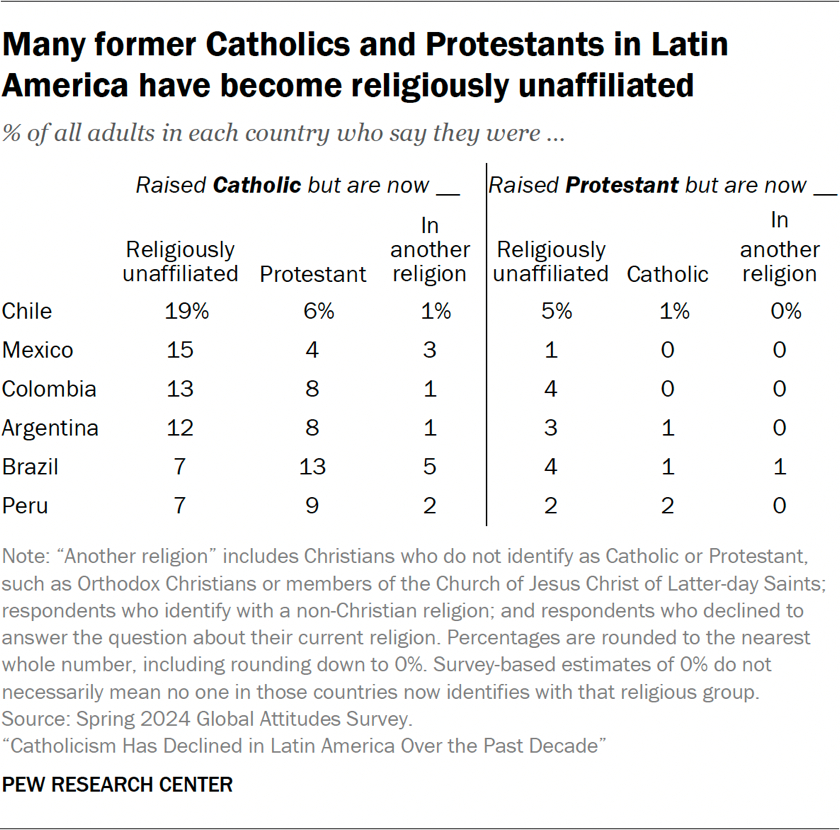

Former Catholics in Latin America tend to identify as either religiously unaffiliated or Protestant, while former Protestants tend to have become “nones.”

Specifically, in four of the Latin American countries, more former Catholics have disaffiliated – meaning they left the religion of their childhood and are now religiously unaffiliated – than have switched to Protestantism or another religion.

For example, 15% of all Mexican adults say they were raised Catholic and are now religiously unaffiliated, while just 4% of Mexicans say they were raised Catholic but are now Protestant.

Brazil is the only country where significantly more former Catholics have become Protestant (13% of all Brazilian adults) than have become religiously unaffiliated (7%). In Peru, former Catholics are about as likely to be Protestant (9% of all Peruvian adults) as to be “nones” (7%).

Meanwhile, former Protestants in Latin America are generally more likely to have disaffiliated than to have become Catholic. For instance, 5% of all Chileans say they were raised Protestant and are now atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” compared with 1% of former Protestants in Chile who now identify as Catholic.

Retention rates

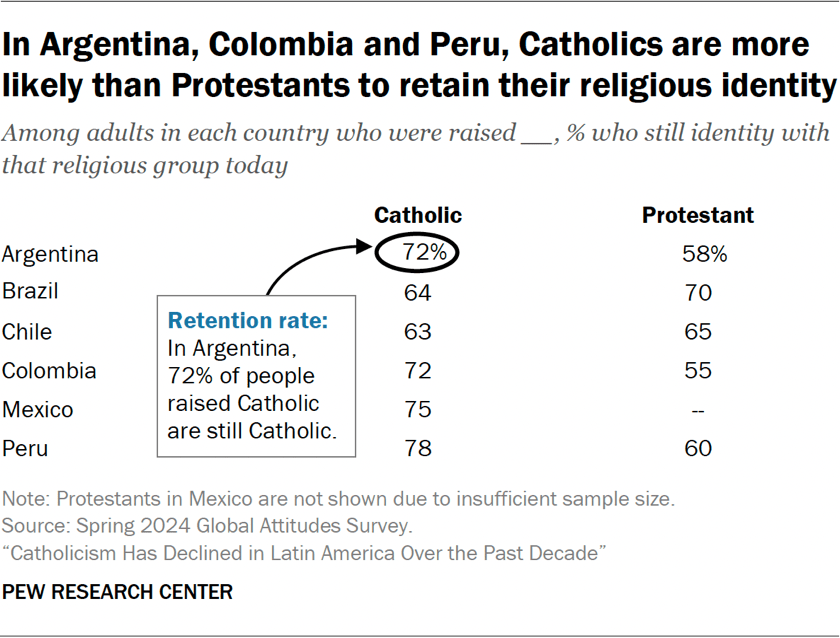

Another way of measuring religious change is to calculate retention rates: Among all the people who say they were raised in a particular religious group, what percentage still describe themselves as belonging to that group today?

Across the region, most people who were brought up Catholic or Protestant have retained the same religious identity as adults.11

In the countries surveyed, between 63% and 78% of people who were raised Catholic still identify as Catholic today. Similarly, between 55% and 70% of those who say they were raised Protestant still describe themselves as Protestant.