Among Indians overall, sex selection during pregnancy is at least in part a result of a cultural preference for sons over daughters, which may be thought of as “son preference” or “daughter aversion,” or both.

A preference for sons seems to be implied in the ancient Hindu epic “Mahabharata,” in which Gandhari is blessed to be a mother of a hundred sons and one daughter.14 Sex selection may not be entirely new, either. Studies have documented female infanticide for decades well before prenatal testing was introduced in the 1970s.15

Because “son preference” is a sensitive topic, measuring it in surveys can be challenging.16 One common approach is to ask parents how many boys and how many girls they would like to have, if given the choice. In the 2019-21 National Family Health Survey (NFHS), 15% of Indian women ages 15 to 49 reported wanting to have more sons than daughters, while just 3% said they wanted more daughters than sons. (The NFHS asks this question of women ages 15 to 49, which covers the birthing span for the vast majority of Indian women. For Pew Research Center survey data on Indian gender attitudes, see “How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society.”)

Rather than attributing the imbalance in sex ratios at birth to “son preference,” some scholars ascribe it to “daughter aversion.”17 Both perspectives are valuable, and they may be subtly, but importantly, different. For example, if a woman has an unplanned pregnancy and chooses to have an abortion after learning that the fetus is female – though she would have continued the pregnancy if it had been male – her choice would be better understood as an actual aversion to bearing a daughter, rather than as a hypothetical preference for bearing a son.

Moreover, son preference and daughter aversion may affect fertility differently: Parents desiring sons may want to continue having children until they reach an ideal number of sons, while those avoiding daughters may only allow male births, resulting in fewer children overall.

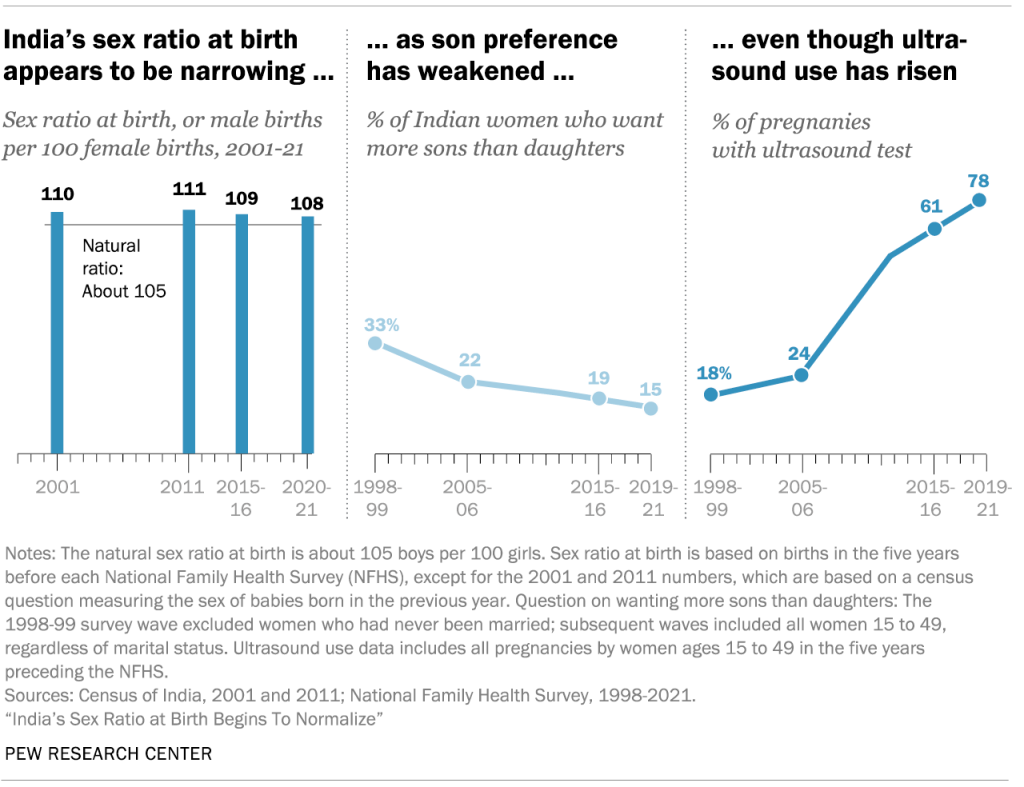

Mathematically, too, sex ratios at birth can be presented in either of two directions: as the number of boys per 100 girls, or as the number of girls per 100 boys. For example, India’s current overall ratio of 108 boys per 100 girls is the same as 93 girls per 100 boys (after rounding to the nearest integer).

The Indian government typically expresses sex ratios as the number of female births per 1,000 male births, reversing the ratio used in most other countries and increasing the base by a factor of 10. By this convention, the current sex ratio at birth in India is 925 girls per 1,000 boys, according to the 2019-21 NFHS.18

Although both ratios are correct, it could be confusing to provide statistics in two different formats. It would also be difficult to disentangle whether large-scale childbearing patterns result primarily from son preference or daughter aversion. For these practical reasons, this report follows the international convention of presenting the ratio of boys per 100 girls and uses “son preference” more or less interchangeably with “daughter aversion.”

To counter the widespread aversion to having daughters in Indian society, the government in 2015 launched a campaign to “Save the girl child, educate the girl child” (Beti Bachao Beti Padhao). Advertisements bearing that slogan often appear on radio and television, as well as on the sides of buses and trucks, especially in Northern India.

While a stated preference for sons (or aversion to daughters) is the main theoretical cause of India’s skewed sex ratio, it is not an exact predictor of actual birth patterns. Instead, the use of prenatal sex screenings, and a subsequent decision to abort female fetuses, more directly result in an elimination of girls from the population.

Prenatal diagnostic technology was first introduced to India in the 1970s in the form of amniocentesis, though that service was prohibitively expensive for all but the most affluent families. Around the early 1980s, a cheaper alternative – ultrasound – was introduced to India as a method of detecting fetal anomalies.19 Ultrasound technology was soon being used for prenatal sex detection in the wealthier parts of the country, but it did not become widely available and affordable outside major cities until the 1990s and even the 2000s.20

Meanwhile, abortion was legalized in 1971. Starting in the 1970s and accelerating in the 1980s, the use of prenatal testing to detect the sex of a fetus, and the use of abortion to prevent the birth of girls and ensure the birth of boys, became increasingly common throughout India.

The practice became so widespread that in 1994, India passed the Prenatal Diagnostic Techniques Act, making it illegal for doctors and other medical service providers to reveal the sex of the fetus to parents. The act threatens violators, including family members who seek information about a fetus’s sex and medical personnel who provide this detail, with fines and even imprisonment.21

Today, ultrasound services for legal health screenings are common throughout India, although they can still be prohibitively expensive for women from low-income families.

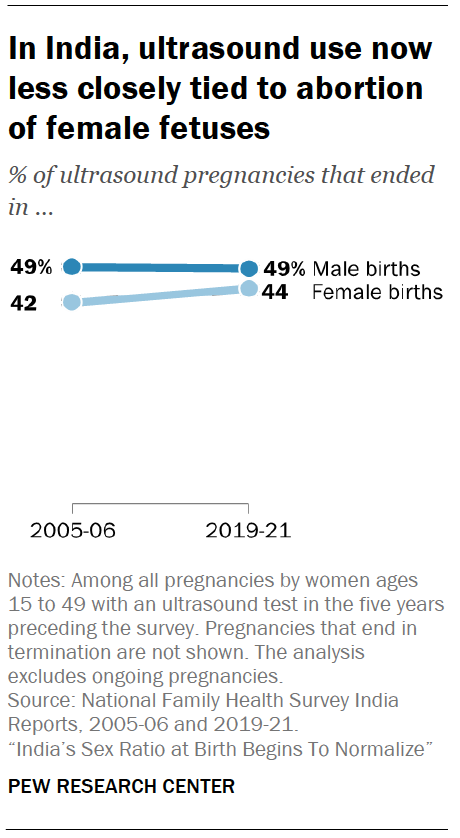

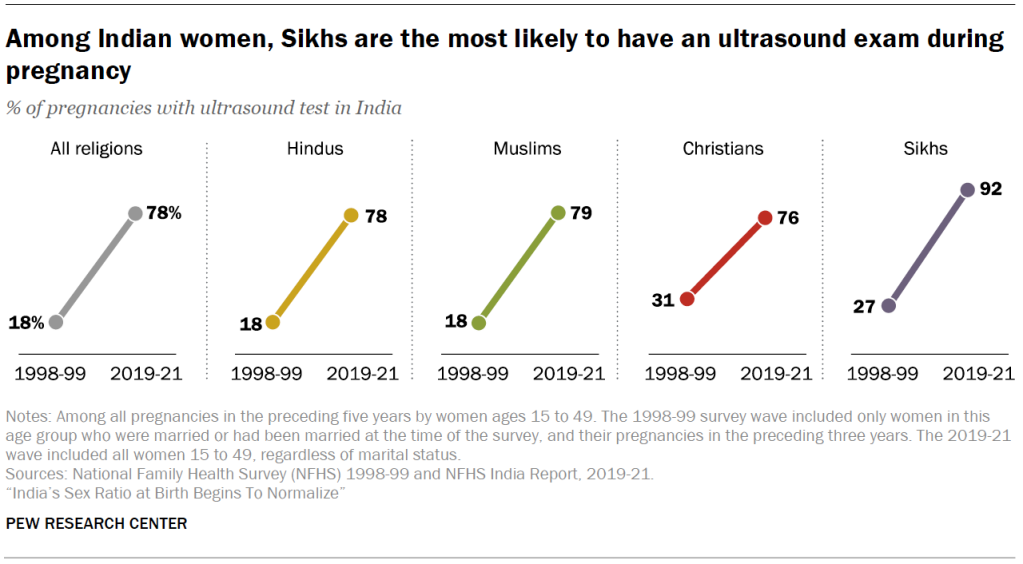

The 2019-21 NFHS found that an ultrasound test was performed on nearly eight-in-ten Indian pregnancies (78%) in the five years leading up to the survey, compared with just one-quarter 0f pregnancies in a similar period before the 2005-06 survey.

Meanwhile, Indian women seem to have become more likely to use ultrasound tests exclusively for medical purposes rather than to facilitate sex selection. Of course, researchers cannot know for sure what a woman’s intention is when she obtains an ultrasound, but an analysis of pregnancy outcomes reveals that the share of male versus female births among “ultrasound pregnancies” (those that involve prenatal testing) is moving toward balance, from 49% male versus 42% female in 2005-06 to 49% versus 44% in 2019-21. (These percentages do not add up to 100%, as some remaining pregnancies ended in abortion, miscarriage, or stillbirth.) Put another way, the sex ratio at birth following ultrasound use during pregnancy is now 109 boys per 100 girls. In the 2005-06 NFHS, it was 118.

There is also evidence that over the past two decades, the underlying preference for sons (or aversion to daughters) in Indian society has weakened. In the 2019-21 NFHS survey, 15% of Indian women of reproductive age reported wanting to have more boys than girls, less than half the share who expressed that desire in the 1998-99 NFHS (33%). Meanwhile, the share of Indian women wanting more daughters than sons remained steady over the same period, at around 3%.

Indeed, a 2019-20 Pew Research Center survey of 29,999 adults across India found that 94% of Indians say it is “very important” for a family to have at least one son, while 90% separately say it is very important for a family to have at least one daughter. This indicates that the vast majority of Indian adults view both sons and daughters as key parts of a family, and only a slightly greater share feel it is imperative to have at least one son. (For more on India’s changing gender norms, see the Center’s report, “How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society.”)

These changes in ultrasound use and son preference also have coincided with socioeconomic advances for women, and better educational opportunities. Currently, fewer than three-in-ten women ages 15 to 49 (28%) have no formal schooling, compared with four-in-ten women in that age group in 2005-06, according to the NFHS.

And, finally, the changes have been underpinned by extensive government efforts to stop sex-selective abortions – not just in the form of advertisements on billboards and buses, but also with stiffer penalties for the illegal use of ultrasound tests for sex screenings and sting operations that have resulted in high-profile arrests of doctors. (Although critics say the government’s attempts to curb sex selection practices have been ineffective or insufficient.)

On the other hand, changes in fertility patterns may be pulling in the opposite direction, helping to perpetuate unnatural sex ratios at birth.

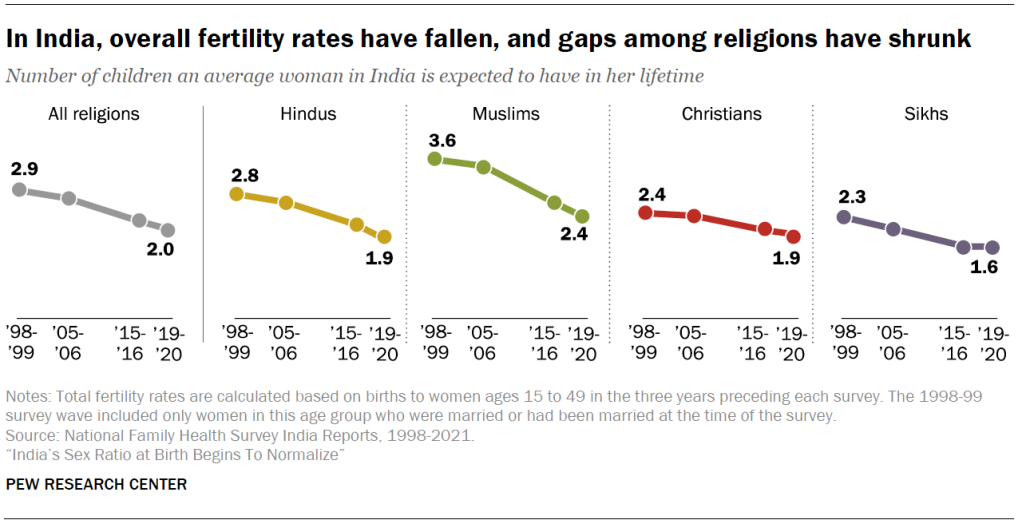

In India and elsewhere around the world, a desire for smaller families is often tied to wider sex ratios: When parents plan to have more than one child, they may accept the birth of a daughter while they wait for a son to be born. But when their ideal family size shrinks to just one child, they might be more motivated to turn to sex selection to ensure the birth of a boy.22 India’s total fertility rate has fallen sharply in the past two decades; in 2019-21, the average Indian woman was expected to have 2.0 children in her lifetime, nearly one child fewer than in 1998-99 (2.9).

Sikhs have seen biggest change in sex ratios, son preference

All of these underlying dynamics have moved at different speeds for different religious groups, and in the past two decades, trends in sex ratios at birth have differed considerably by religion. Sikhs, who had the widest gap in the sex ratio at birth in the early 2000s, have seen the fastest narrowing in the past two decades.

Sikhs are on average the wealthiest of India’s major religious groups, and they are geographically concentrated in the economically advanced northwestern states of Punjab and Haryana, where ultrasound services were more common than in other parts of India as early as the 1990s. By the time the Sikh sex ratio peaked (at 130) in the early 2000s, Sikh women were obtaining ultrasounds at about twice the rate of Indian women overall.

Hindus tend to receive less education than Sikhs and are poorer, on average. Even today, ultrasound use among Hindus lags far behind Sikhs. Hindus and Muslims experienced a slight increase in the share of male births between the 2001 and 2011 censuses, but in recent years they, too, have seen a decline. In particular, Muslims’ sex ratio now is close to the natural level. Meanwhile, Christians have long had the least male-biased ratio.

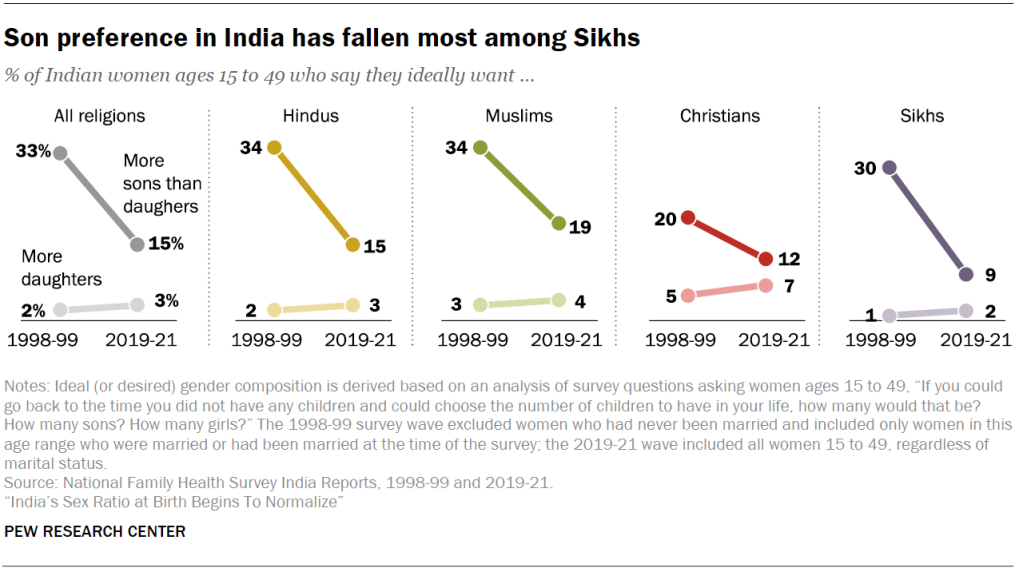

Over the past two decades, all of India’s major religious groups experienced a waning preference for sons. The change among Sikhs is the most pronounced. In the most recent NFHS, just 9% of Sikh women said they wanted more sons than daughters, compared with three-in-ten in the 1998-99 survey.

By this measure, Sikh women now are close to Christians in their low levels of expressed preference for having more boys than girls. Christians have consistently shown a relatively weak preference for sons. In the 2019-21 NFHS, 12% said they would prefer to have more sons than daughters, compared with 20% in 1998-99.

Muslims and Hindus, who together started out with India’s highest levels of son preference – as measured in surveys – have seen a moderate decline, though Muslims now have the greatest share of women saying they would prefer more sons than daughters (19% in 2019-21 vs. 34% in 1998-99), followed by Hindus (15% vs. 34%).

When it comes to the question of preferring daughters over sons, the change over the past two decades has been modest. Among Christians in India, 7% now say they would prefer to have more daughters than sons, compared with smaller shares of Muslims (4%), Hindus (3%) and Sikhs (2%).

Ultrasound use is becoming more common across India’s religious groups

Meanwhile, as ultrasound tests have become more affordable and accessible, the gaps in use of ultrasounds among religious groups have narrowed significantly.

In 2019-21, an ultrasound test was performed among approximately eight-in-ten pregnancies by Muslim women in the prior five years preceding the survey, which is 12 percentage points lower than the figure for Sikh women. Roughly 15 years earlier, in the 2005-06 NFHS, Sikh women were more than twice as likely as Muslims to have had an ultrasound test during pregnancy (47% vs. 20%).

Still, ultrasound use remains most common among Sikhs, while other religious groups lag far behind. The religious gaps are partly due to geographic distributions. Most Sikhs reside in India’s relatively affluent North, where the vast majority of all women (88%) have an ultrasound during pregnancy.

A woman’s wealth and education are robust predictors of ultrasound use: Indian women from the wealthiest households are 35 points more likely than those from the poorest households to have an ultrasound during pregnancy (92% vs. 57%).23 Ultrasound use is much more common among women with 12 or more years of formal schooling than among women who have no formal education (89% vs. 60%). There is also a significant urban versus rural gap in ultrasound use during pregnancy (87% vs. 75%).

Fertility tied to variations in sex imbalance at birth among religious groups

Aside from wealth and education, fertility also may play a role, because parents who plan to have fewer children may be more motivated to have an abortion to ensure having a boy. In India, fertility has declined across all groups in recent decades, though Sikhs have consistently been the religious group with the lowest rates, and Muslims the highest. The fertility rate among Sikhs has fallen from an average of 2.3 children per woman in 1998-99 to 1.6 in 2019-21; among Muslims, it has dropped from 3.6 children to 2.4 over the same period.

In societies with son preference but no prenatal sex selection, families often keep having children to achieve the ideal number of boys. For example, they may continue childbearing if their first child is a girl, though they might stop having children if their first child is a boy. In those communities, the overall gender composition of births is balanced, though boys are overrepresented in smaller families, while girls tend to grow up in larger families as their parents continued to try having a son.

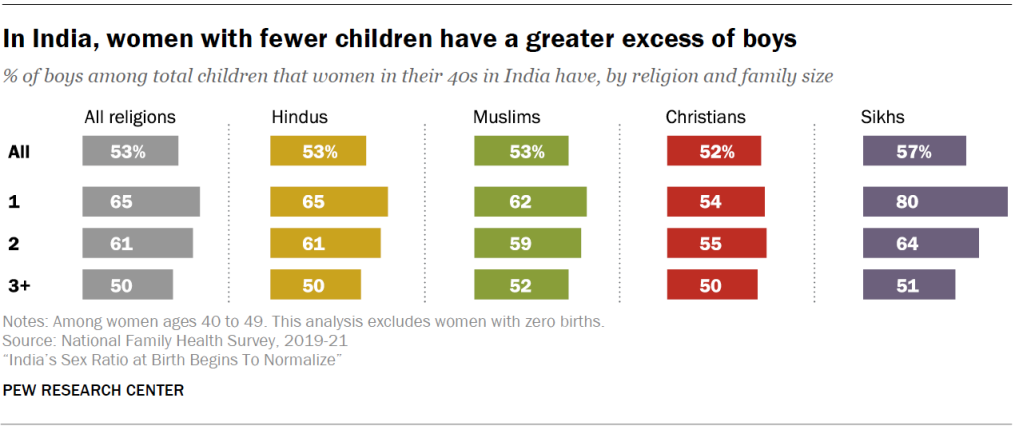

Christians in India are an example: The gender composition of children born to Christian women varies depending on the mother’s fertility – ranging from 55% of boys among women who had only two births to 50% among women with three or more births. (This data is based on women in their 40s, who have typically completed their childbearing.) The average gender composition of Christian children is largely balanced, with roughly 52% boys.

The overall gender balance becomes skewed when sex-selective abortion – which allows parents to prevent the birth of a child whose sex is not wanted – is common. In such communities, male births are even more overrepresented among women with fewer children than they would be if there was no prenatal sex selection, because sex selection makes it possible to achieve a desired number of boys within a limited number of total births.

Among India’s major religious groups, Sikhs have the most skewed gender composition of children in small nuclear families. Among Sikh women in their 40s who have given birth only once, 80% had a male child. The same is true of 65% of Hindus and 62% of Muslims. By contrast, the share of boys born to Christian women with just one child is closer to normal, at 54%.

Meanwhile, the overall gender composition of children tends to skew less in communities with a greater number of large families. Theoretically, if women did not practice sex selection and instead kept having children until their ideal number of sons were born, their gender composition would be more balanced. Indeed, Muslim women in their 40s have, on average, given birth to more boys (1.9) than Sikh women have (1.4). The gender composition of children in Muslim families is less skewed: 53% boys, compared with 57% among Sikhs. In other words, high fertility rates tend to help reduce sex imbalances. (Inversely, Muslim women having more children may be a result of their tendency to continue trying for sons, instead of turning to sex-selective abortions.)

The relatively moderate bias toward males in the gender composition of Muslim children in India also may reflect an acceptance of having daughters. Muslim women in their 40s have had an average of 1.7 girls, compared with 1.4 among Hindus and 1.2 among Christians. Sikhs seem to hold a relatively strong aversion to daughters, because their families are relatively small and have a disproportionately high number of boys: The average Sikh woman in her 40s has 1.4 boys and 1.1 girls.

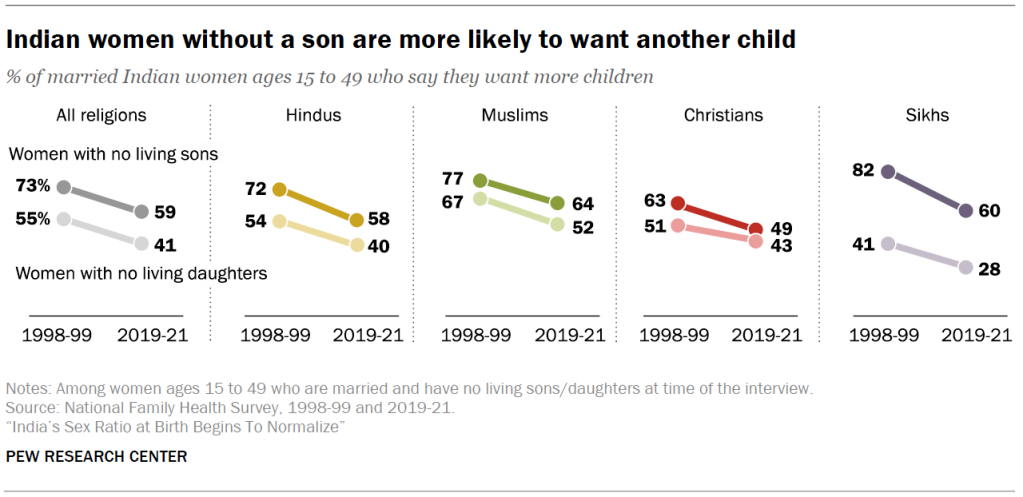

A closer look at NFHS data reveals yet another indicator of widespread son preference: In India, married women with no living sons are much more likely than those with no living daughters to say they want to have more children(59% vs. 41%). Such gender bias in fertility desire is most striking among Sikhs. In the 2019-21 survey, six-in-ten married Sikh women with no living sons said they want to have more children, double the share of Sikhs with no living daughters who voiced the same desire (28%).

While Muslim women (ages 15 to 49) with no living sons tend to express a strong intention of continued childbearing, Muslims with no living daughters are also the most likely of women in all major Indian religious groups to say they want more children. Christians continue to stand out for comparatively weak gender discrimination in decisions about childbearing. About half of Christian women with no living sons want more children, only 6 points greater than those with no living daughters.

Moreover, whether Indian women have a living son at the time of their pregnancy strongly predicts sex selection: Among women with no living sons, the sex ratio at birth after ultrasound use is heavily male-biased, at 118 boys per 100 girls, compared with a naturally balanced ratio among women with sons (105).

Wealth, education and regional distribution tied to differences among religious groups

These differences in fertility notwithstanding, it is difficult to say with certainty why religious groups have followed such different paths when it comes to sex selection more broadly. The dynamic may be tied to the country’s overall rise in education and wealth, which does not always have the same effect across socioeconomic levels.

Among Hindus and Muslims, who have relatively low educational attainment and wealth, it seems that socioeconomic advancement in the 2000s facilitated abortions by making ultrasound testing more affordable and accessible. But among Sikhs, who were wealthier and have more education to begin with, socioeconomic advancement seems to have reduced abortions by dampening the desire to have sons or avoid daughters.24

This diverging trend in sex ratios across socioeconomic levels has been observed elsewhere. Studies in South Korea, for example, show that the most educated groups were the first to experience a widening in the ratio, in the 1980s, before the same trend spread to others. Later, South Korea’s most educated groups also were the first to experience a shift back toward the natural ratio.25 Demographers including Christophe Z. Guilmoto refer to such groups as “pioneers” in the sex ratio transition.26

Another major factor that underlies differences among religious groups is their regional distribution. With roughly 1.4 billion people spread across 28 states and eight union territories, Indians are dispersed across widely differing economies, with a range of histories, education levels and family norms. Members of one religious group in the North may have more in common with other Northern Indians than they do with members of their own religion in the South.

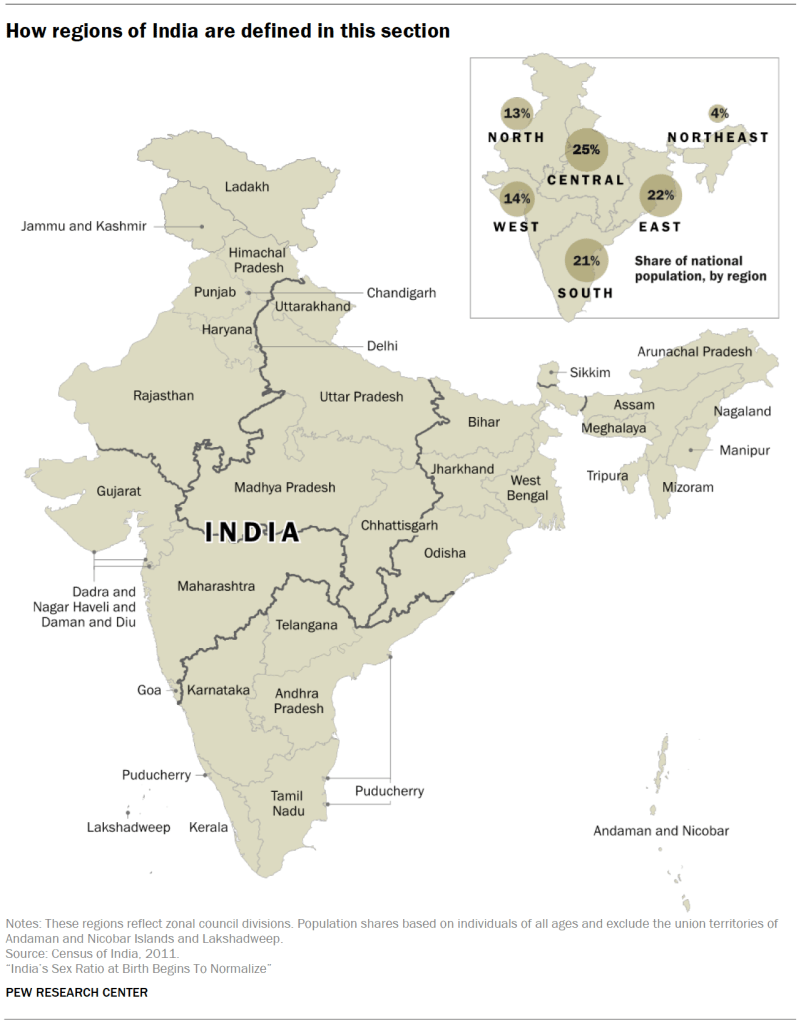

There are several possible ways to examine the regional distribution of religious groups in India. This report focuses on the regions of India’s six administrative zones – North, Northeast, Central, East, South and West – with a brief mention of some noteworthy states.

Hindus are a majority in most of India’s states and union territories. Most Muslims reside as religious minorities in the Central and Eastern states. Muslims make up a majority in Jammu and Kashmir, a union territory adjacent to Pakistan, and in the sparsely populated archipelago of Lakshadweep.

The largest numbers of Christians live as religious minorities in the Southern states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Their biggest population shares are in the smaller Northeastern states that border China, Bhutan, Myanmar or Bangladesh, such as Mizoram, Nagaland and Meghalaya. Sikhs mostly reside in the northwestern state of Punjab, where they make up a majority (58%). (See Pew Research Center’s report, “Religious Composition of India.”)

Northern, Western and Southern India are the wealthiest regions, with higher levels of education and earlier access to advanced health care systems such as ultrasound screenings. The Central, Eastern and Northeastern states tend to be poorer, with lower levels of urbanization and economic development.

Historically, cultural norms on family and marriage also vary considerably by region. Generally speaking, Northern Indian family norms have been strictly patrilineal: Sons inherit property, while daughters move into their husband’s home after marriage and usually do not inherit or own property. Even beyond the nuclear household, money, gifts and other resources in the form of dowry flow in one direction – from the woman’s natal family to her husband’s family.27

Indians in the South and the Northeast practice less stringent patrilineal norms. Parents expect their daughters as well as their sons to help in old age, and it is socially acceptable for married daughters to inherit property and help their birth family financially. Women in the South also face fewer restrictions on their mobility and job opportunities than those who live in the North and Western states.28

To be sure, gender norms are not uniform within regions – or even within families – and cultures everywhere are always undergoing change. A 2019-20 Pew Research Center survey finds that while women in India’s Southern states generally fare better on education and health measures than women in other parts of the country, some Southern Indians may still espouse traditional, patriarchal values. For example, while Kerala tends to be most consistently egalitarian in gender attitudes, neighboring Tamil Nadu sometimes stands out with more male-biased views. Tamil Nadu residents are about twice as likely as people in Kerala to agree sons should have the primary responsibility for their parents’ last rites or burial rituals (56% vs. 30%). They are also more likely to say sons should have greater rights to inheritance (27% vs. 12%). (See Pew Research Center’s survey report, “How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society.”)

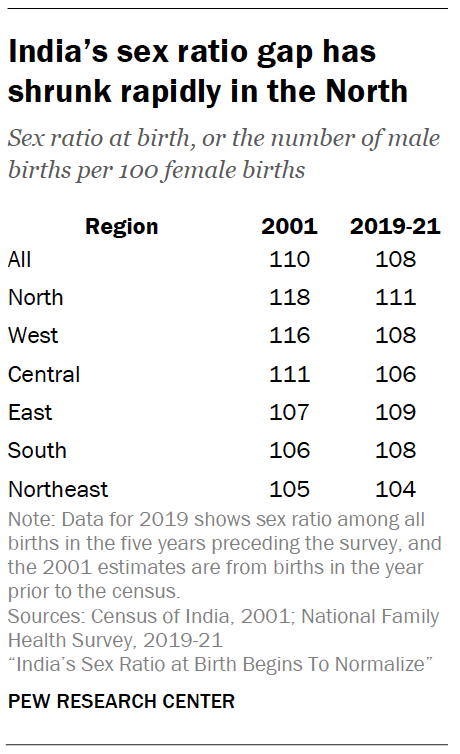

India’s sex ratio at birth is slightly more skewed in the North (111) than in the South (108), according to the 2019-21 NFHS. The North-South divide was more pronounced in the past. In the 2001 census, for example, the sex ratio at birth was most heavily skewed in the North (118) and almost balanced in the South (106).

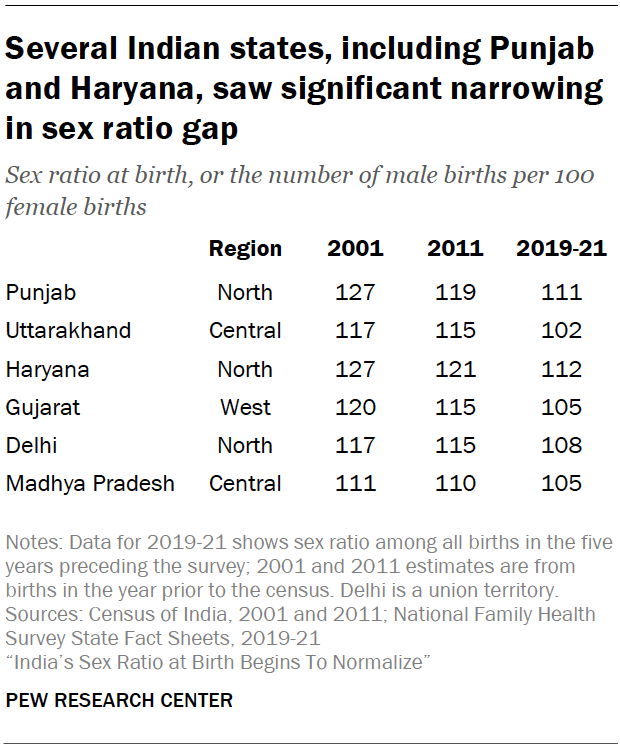

Over the past two decades, the sex ratio gap has fallen most in India’s North region, driven by states such as Punjab, Haryana and Delhi. Today, the sex ratio gap in the North is 111 boys per 100 girls, close to the Indian average, according to NFHS data.

India’s Southern and Northeastern regions have consistently had sex ratios close to the natural balance, although the sex ratio in the South has recently started to skew toward males. In the relatively affluent South, the sex ratio at birth now is 108.

The Central and Eastern states have a moderate skew, ranging between 106 and 111 in the past two decades. These two regions are characterized by dense populations, low economic development and educational attainment, and a concentration of Muslims. Women in this area are more likely to prefer sons than women in any other region, with 20% of women who would want more sons than daughters in 2019. Central India’s moderate sex imbalance over the past two decades is likely due to limited access to ultrasounds and their higher fertility rate.

Spotlight on Sikhs: Rapid changes in recent decades

Sikhs’ concentration in northwestern India is often cited as a key factor in their male biased ratio, and Sikhs’ unique caste composition also seems to play a critical role.

The vast majority of India’s Sikhs live in the northwestern states of Punjab (where they account for 58% of the population) and Haryana (where they are a minority). For many years, Punjab and Haryana had heavily skewed sex ratios, at 127 boys per 100 girls in 2001 and about 120 in 2011, according to the census. Traditionally, Indians – not just Sikhs – who live in this region have tended to follow strict patrilineal norms, such as giving sons greater access to inheritances.

Sex ratios at birth have been strongly male-biased among both Sikhs and Hindus in Punjab, which has a Sikh majority, and Haryana, where Sikhs are about 5% of the population. In the 2011 census, Hindus living as a minority in Punjab had a sex ratio of 116 boys per 100 girls. In Haryana, where Hindus are the majority of the population, there were 123 boys per 100 girls at birth. However, in each state the sex ratio was even more male-biased among Sikhs (121 in Punjab and 127 in Haryana).

In addition, many Sikhs in Punjab and Haryana belong to the land-owning Jat caste that passes ancestral properties down through male lines. Today, Sikhs’ sex ratio at birth (110) is not very different from the national average (108), neither are the overall ratios in Punjab (111) and Haryana (112), according to births in the five years prior to the 2019-21 NFHS.

Much of the movement in Sikhs’ sex ratio in recent decades can be attributed to upper-caste families – who are generally more educated, affluent and likely to own land.29 The sex ratio among upper-caste Sikhs was far more skewed than among lower-caste Sikhs in the 1990s and early 2000s. Over the past two decades, the ratio has narrowed sharply among upper-caste Sikhs. For instance, Sikh women in the higher “General Category” caste saw a 30-point change between the 2005-06 and 2019-21 waves of the NFHS (151 vs. 121, respectively), compared with a 5-point change among Sikhs in the lower “Scheduled Caste” category (107 vs. 102).30 As upper-caste families account for about 40% of all Sikhs, they play an important role in shaping Sikhs’ overall sex ratio at birth. (For a deeper analysis of the connections between caste and sex selection among Indians overall and within religious groups, see “What role does caste play?”)

If the 2019-21 NFHS is accurate, the Sikh “correction” toward a more natural ratio in the past decade means that Sikhs (with a sex ratio at birth of 110) are no longer very different from Hindus (109) on this measure.

Spotlight on Christians: Low rates of sex selection

Among Christians, the sex ratio at birth has consistently stayed between 103 and 105 in each of the datasets in this analysis. Partially due to their concentration in the South, Christian women ages 15 to 49 are less likely than the average Indian woman in this age group to say they would prefer to have more sons than daughters (12% vs. 15% for all Indian women ages 15 to 49) and more likely to say they would prefer to have more daughters than sons (7% vs. 3%, respectively).

Some scholars suggest Christians’ balanced sex ratio at birth is due in part to the religion’s history in India, and the prevalence of Christian social programs and cultural practices that focus on girls and women.

Many of India’s Christians are descendants of Dalit Hindus who converted to Christianity in part to escape caste-based discrimination. Large-scale conversions are reported to have taken place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in connection with famines, natural disasters, epidemics and other crises that resulted in economic hardship.31 After conversion, missionary organizations often provided low-caste Christians with educational opportunities, and converts could take jobs that previously had been denied to them based on caste status.

Some scholars suggest that low-caste Hindus who converted to Christianity gained more than just material benefits. Converting may have given former Dalit Hindus a new self-image, eased the transition away from their traditional, “unclean” occupations and made new educational opportunities possible for their children.32

Women, in particular, may have benefited from these types of changes. Christian missions in India have emphasized evangelical work among women since the 19th century, operating schools for girls as well as for boys. There were also missionary programs dedicated to educating women and training them for employment, such as the Mukti (Salvation) Mission.33 In addition, many Christian organizations prioritize maternal and child health by improving women’s access to health care facilities. Some scholars trace Christian missionary work to long-lasting benefits for Christians and cite the Christian emphasis on empowering women as a partial explanation for Christian girls’ better health outcomes.34

This history may help explain why Christians are the least likely of India’s religious groups to engage in sex-selective abortions, and why the share of Christians who would prefer to have more daughters than sons (7%) is several percentage points greater than other religious groups. Nevertheless, Pew Research Center estimates that Christians have practiced sex selection at least to some extent, given the roughly 53,000 female births missing among Christians in India between 2000-19. To some degree, the estimate reflects the pervasive influence of son preference throughout Indian society. Christians, especially those who live in the North and West, may not be immune to this bias and the practice of sex selection. For instance, in the most recent census, the sex ratio at birth among Christians in these two regions was around 110 boys per 100 girls.