The majority of U.S. adults have internet access, including those who are living with chronic disease.

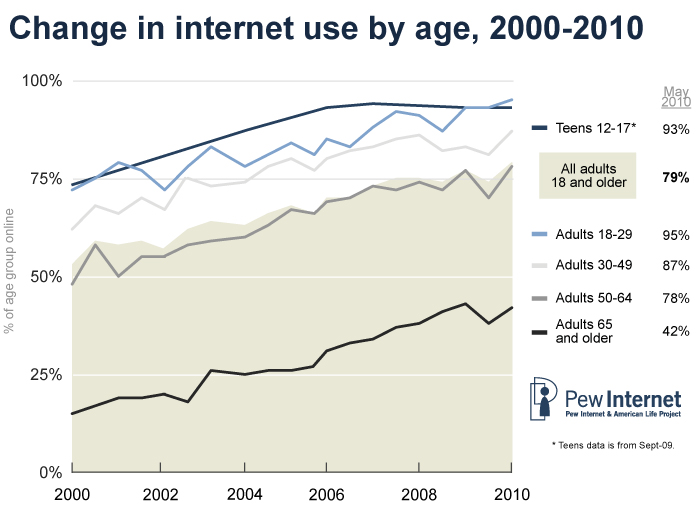

In 1995 only about 1 in 10 American adults had access to the internet. In 2000, it was up to nearly half of adults. Now, about 75% of adults and 95% teenagers in the U.S. have internet access.1

Survey data from the Pew Internet Project and the California HealthCare Foundation show that while internet access is the norm, adults living with chronic disease are significantly less likely than healthy adults to go online:2

- 81% of adults reporting no chronic diseases go online.

- 62% of adults living with one or more chronic disease go online.

It is important to note that 80% of adults who provide care to their parents or another loved one have internet access. So while internet access is unevenly distributed, especially among age groups, many people have “second degree” access.

Broadband changed us as internet users; mobile is the new game-changer.

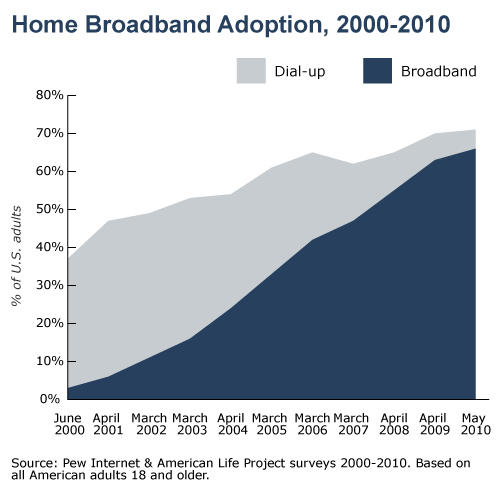

In the year 2000 only 5% of households had broadband access. Now, two-thirds of Americans have broadband at home. One Pew Internet study found that dial-up users take part in an average of 3 activities per day while broadband users take part in 7.1

85% of American adults have a cell phone. Six in 10 American adults go online wirelessly with a laptop or mobile device. Mobile access has erased the digital divide. A mobile device is the internet for many people. Information has become portable, personalized, and participatory.2

Cancer patients are likely to be engaged in their care.

The Center for Studying Health System Change has found that people living with cancer are more likely than other chronic-disease groups to be actively engaged in their care, which has significant implications for health outcomes:

Individuals identified as highly activated according to the measure are more likely to obtain preventive care, such as health screenings and immunizations, and to exhibit other behaviors known to be beneficial to health. These include maintaining good diet and exercise practices; self-management behaviors, such as monitoring their condition and adherence to treatment protocols; and health information seeking behaviors, such as asking questions in the medical encounter and using quality information to select a provider. 3

Pew Internet’s research adds to this picture of an activated patient population by showing that the internet, particularly social media, enables people to engage with each other and with health care in ways that were almost unimaginable a decade ago.

Health professionals dominate the information mix.

More than any other group, people living with chronic disease remain strongly connected to offline sources of medical assistance and advice:

- 93% of adults living with chronic disease ask a health professional for information or assistance in dealing with health or medical issues.

- 60% ask a friend or family member.

- 56% use books or other printed reference material.

- 44% use the internet.

- 38% contact their insurance provider.

- 6% use another source not mentioned in the list.

By comparison, adults who report no chronic conditions are significantly more likely to turn to the internet as a source of health information and less likely to contact their insurance provider.4

This comports with the findings of the National Cancer Institute’s own Health Information National Trends Survey, which finds that people’s “trust in information from healthcare professionals had increased while their trust in health information from the Internet had waned” between 2002 and 2008.5

People learn from each other, not just from institutions and health professionals.

An upcoming report from the Pew Internet Project and the California HealthCare Foundation shows, however, that people turn to health professionals for some types of information and to fellow patients, family, and friends for other types.

Professionals, such as doctors and nurses, are the most likely source for people who want to get an accurate medical diagnosis, information about alternative treatments, a recommendation for a doctor or specialist, and a recommendation for a hospital or other medical facility.

Peers, such as fellow patients, family, and friends, are the most likely source for people who want emotional support in dealing with a health issue or a quick remedy for an everyday health issue.

When it comes to practical advice for coping with day-to-day health situations, people are as likely to turn to peers as they are to turn to professionals.

Most of these conversations happen offline, but the upcoming report also shows that about one in five internet users has gone online to find others who might have health concerns similar to theirs. The internet connects people across geographical boundaries, which is especially important for people living with rare cancers.

The social life of health information is robust.

Eight in ten internet users go online to look for health information, no matter their health status. Searching online for certain topics is almost universally popular: specific disease information, treatment options, and prescription drug information, for example.

Social network sites are important information hubs for many Americans, including a growing group of older adults.6 The internet is not just an information vending machine. It is a social, mobile communications device that can fit in someone’s pocket, helping them wherever they are to connect with just-in-time information and support.

Interestingly, there are two online activities which stand out among people living with chronic disease: blogging and online health discussions. When other demographic factors are held constant, having a chronic disease significantly increases an internet user’s likelihood to say they work on a blog or contribute to an online discussion, a listserv, or other online group forum that helps people with personal issues or health problems.

Living with chronic disease is also associated, once someone is online, with a greater likelihood to access user-generated health content such as blog posts, hospital reviews, doctor reviews, and podcasts. These resources allow an internet user to dive deeply into a health topic, using the internet as a communications tool, not simply an information vending machine.

The online conversation cannot be controlled, but trusted sources can contribute by making it easy for internet users to find and share up-to-date information. For example, instead of publishing only in PDF, organizations can publish in a way that allows someone to grab a chart, a data point, or an image and link back to specific part of a document. Publicly-available data sets can also be posted in computable formats.

The internet is like a secret weapon – if someone has access to it.

The deck is stacked against people living with chronic disease. They are disproportionately offline. They often have complicated health issues, not easily solved by the addition of even the best, most reliable, medical advice.

And yet, those who are online have a trump card. They have each other. Pew Internet’s research finds that having a chronic disease increases the probability that an internet user will share what they know and learn from their peers. They unearth nuggets of information. They blog. They participate in online discussions. And they just keep going.

Broadband + mobile + chronic disease = our future.

Broadband and mobile internet access is spreading to more Americans, making them more likely to access health information whenever and wherever they need it. The always-on, always-with-you internet enhances people’s online experience and creates a positive feedback loop, reinforcing their interest in using the internet to gather and share information. Two waves are crashing together – an increase in technology and an increase in chronic disease – and both are driving us forward toward engagement in online health resources.