Text messaging explodes as teens embrace it as the centerpiece of their communication strategies with friends.

The mobile phone has become the favored communication hub for the majority of American teens.1

Cell-phone texting has become the preferred channel of basic communication between teens and their friends, and cell calling is a close second. Some 75% of 12-17 year-olds now own cell phones, up from 45% in 2004. Those phones have become indispensable tools in teen communication patterns. Fully 72% of all teens2 – or 88% of teen cell phone users — are text-messagers. That is a sharp rise from the 51% of teens who were texters in 2006. More than half of teens (54%) are daily texters.

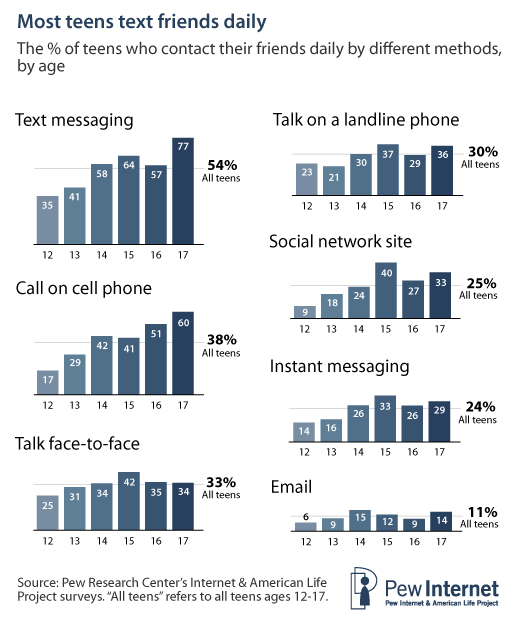

Among all teens, their frequency of use of texting has now overtaken the frequency of every other common form of interaction with their friends (see chart below).

Fully two-thirds of teen texters say they are more likely to use their cell phones to text their friends than talk to them to them by cell phone.

One in three teens sends more than 100 text messages a day, or 3000 texts a month.

Daily text messaging by teens to friends has increased rapidly since early 2008. Some 38% of teens were daily texters in February 2008, and that has risen to 54% of teens who use text daily in September 2009. Of the 75% of teens who own cell phones, 87% use text messaging at least occasionally. Among those texters:

- Half of teens send 50 or more text messages a day, or 1,500 texts a month, and one in three send more than 100 texts a day, or more than 3,000 texts a month.

- 15% of teens who are texters send more than 200 texts a day, or more than 6,000 texts a month.

- Boys typically send and receive 30 texts a day; girls typically send and receive 80 messages per day.

- Teen texters ages 12-13 typically send and receive 20 texts a day.

- 14-17 year-old texters typically send and receive 60 text messages a day.

- Older girls who text are the most active, with 14-17 year-old girls typically sending 100 or more messages a day or more than 3,000 texts a month.

- However, while many teens are avid texters, a substantial minority are not. One-fifth of teen texters (22%) send and receive just 1-10 texts a day or 30-300 a month.

Calling is still a central function of the cell phone for teens and for many teens, voice is the primary mode of conversing with parents.

Among cell-owning teens, using the phone for calling is a critically important function, especially when it comes to connecting with their parents. But teens make and receive far fewer phone calls than text messages on their cell phones.

Teens typically make or receive 5 calls a day. White teens typically make or receive 4 calls a day, or around 120 calls a month, while black teens exchange 7 calls a day or about 210 calls a month and Hispanic teens typically make and receive 5 calls a day or about 150 calls a month.

Girls more fully embrace most aspects of cell phone-based communication.

As we see with other communicative technologies and applications, girls are more likely than boys to use both text messaging and voice calling and are likely to do each more frequently.

- Girls typically send and receive 80 texts a day; boys send and receive 30.

- 86% of girls text message friends several times a day; 64% of boys do the same.

- 59% of girls call friends on their cell phone every day; 42% of boys call friends daily on their cell phone.

Girls are also more likely than boys to text for social reasons, to text privately, and to text about school work.

- 59% of girls text several times a day to “just say hello and chat”; 42% of boys do so.

- 84% of girls have long text exchanges on personal matters; 67% of boys have similar exchanges.

- 76% of girls text about school work, while 64% of boys text about school.

For parents, teens’ attachment to their phones is an area of conflict and regulation.

Parents exert some measure of control over their child’s mobile phone – limiting its uses, checking its contents and using it to monitor the whereabouts of their offspring. In fact, the latter is one of the primary reasons many parents acquire a cell phone for their child. However, with a few notable exceptions, these activities by parents do not seem to impact patterns of cell phone use by teens.

- 64% of parents look at the contents of their child’s cell phone and 62% of parents have taken away their child’s phone as punishment.

- 46% of parents limit the number of minutes their children may talk and 52% limit the times of day they may use the phone.

- 48% of parents use the phone to monitor their child’s location.3

- Parents of 12-13 year-old girls are more likely to report most monitoring behavior.

- Limiting a child’s text messaging does relate to lower levels of various texting behaviors among teens – these teens are less likely to report regretting a text they sent, or to report sending sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude images by text (also known as “sexting”).

- Teens whose parents limit their texting are also less likely to report being passengers in cars where the driver texted behind the wheel or used the phone in a dangerous manner while driving.

Most schools treat the phone as a disruptive force that must be managed and often excluded from the school and the classroom.

Even though most schools treat the phone as something to be contained and regulated, teens are nevertheless still texting frequently in class.

- 12% of all students say they can have their phone at school at any time.

- 62% of all students say they can have their phone in school, just not in class.

- 24% of teens attend schools that ban all cell phones from school grounds.

- Still, 65% of cell-owning teens at schools that completely ban phones bring their phones to school every day.

- 58% of cell-owning teens at schools that ban phones have sent a text message during class.

- 43% of all teens who take their phones to school say they text in class at least once a day or more.

- 64% of teens with cell phones have texted in class; 25% have made or received a call during class time.

Cell phones help bridge the digital divide by providing internet access to less privileged teens. Still, for some teens, using the internet from their mobile phone is “too expensive.”

Teens from low-income households, particularly African-Americans, are much more likely than other teens to go online using a cell phone. This is a pattern that mirrors Pew Internet Project findings about adults and their cell phones.

- 21% of teens who do not otherwise go online say they access the internet on their cell phone.

- 41% of teens from households earning less than $30,000 annually say they go online with their cell phone. Only 70% of teens in this income category have a computer in the home, compared with 92% of families from households that earn more.

- 44% of black teens and 35% of Hispanic teens use their cell phones to go online, compared with 21% of white teens.

Cell phones are seen as a mixed blessing. Parents and teens say phones make their lives safer and more convenient. Yet both also cite new tensions connected to cell phone use.

Parents and their teenage children say they appreciate the mobile phone’s enhancement of safety and its ability to keep teens connected to family and friends. For many teens, the phone gives them a new measure of freedom. However, some teens chafe at the electronic tether to their parents that the phone represents. And a notable number of teens and their parents express conflicting emotions about the constant connectivity the phone brings to their lives; on the one hand, it can be a boon, but on the other hand, it can result in irritating interruptions.

- 98% of parents of cell-owning teens say a major reason their child has the phone is that they can be in touch no matter where the teen is.

- 94% of parents and 93% of teens ages 12-17 with cell phones agreed with the statement: “I feel safer because I can always use my cell phone to get help.” Girls and mothers especially appreciate the safety aspects of cell ownership.

- 94% of cell users ages 12-17 agree that cell phones give them more freedom because they can reach their parents no matter where they are.

- 84% of 12-17 year-old cell owners agree that they like the fact that their phone makes it easy to change plans quickly, compared with 75% of their parents who agree with that sentiment.

- 48% of cell-owning teens get irritated when a call or a text message interrupts what they are doing, compared with 38% of the cell-owning parents.

- 69% of cell-owning teens say their phone helps them entertain themselves when they are bored.

- 54% of text-using teens have received spam or other unwanted texts.

- 26% have been bullied or harassed through text messages and phone calls.

Cell phones are not just about calling or texting – with expanding functionality, phones have become multimedia recording devices and pocket-sized internet connected computers. Among teen cell phone owners:

Teens who have multi-purpose phones are avid users of those extra features. The most popular are taking and sharing pictures and playing music:

- 83% use their phones to take pictures.

- 64% share pictures with others.

- 60% play music on their phones.

- 46% play games on their phones.

- 32% exchange videos on their phones.

- 31% exchange instant messages on their phones.

- 27% go online for general purposes on their phones.

- 23% access social network sites on their phones.

- 21% use email on their phones.

- 11% purchase things via their phones.

The majority of teens are on family plans where someone else foots the bill.

There are a variety of payment plans for cell phones, as well as bundling plans for how phone minutes and texts are packaged, and a variety of strategies families use to pay for cell phones. Teens’ use of cell phones is strongly associated with the type of plan they have and who pays the phone bills.

- 69% of teen cell phone users have a phone that is part of a contract covering all of their family’s cell phones.

- 18% of teen cell phone users are part of a prepaid or pay-as-you-go plan.

- 10% of teen cell phone users have their own individual contract.

When one combines type of plan with voice minutes, the most common combination is a family plan with limited voice minutes – one in three teen cell phone users (34%) are on this type of plan. One in four teen cell phone users (25%) are on a family plan with unlimited minutes.

Over half of all teen cell phone users are on family plans that someone else (almost always a parent) pays for entirely—this figure jumps to two-thirds among teens living in households with incomes of $50,000 or more. At the same time, low income teens are much less likely to be on family plans. Among teens living in households with incomes below $30,000, only 31% are on a family plan that someone else pays for. In this group, 15% have prepaid plans that someone else pays for, and 12% have prepaid plans that they pay for entirely themselves. Black teens living in low income households are the most likely to have prepaid plans that they pay for themselves.

Unlimited plans are tied to increases in use of the phone, while teens on “metered” plans are much more circumspect in their use of the phone.

Fully three-quarters of teen cell phone users (75%) have unlimited texting. Just 13 percent of teen cell phone users pay per message. Those with unlimited voice and texting plans are more likely to call others daily or more often for almost every reason we queried – to call and check in with someone, to coordinate meeting, to talk about school work or have long personal conversations. Teens with unlimited texting typically send and receive 70 texts per day, compared with 10 texts a day for teens on limited plans and 5 texts a day for teens who pay per message.

4% of teens say they have sent a sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude image of themselves to someone via text message

A relatively small number of teens have sent and received sexually suggestive images by text:

- 15% of teens say they have received a sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude image of someone they know by text.

- Older teens are more likely to receive “sexts,” than younger teens

- The teens who pay their own phone bills are more likely to send “sexts”: 17% of teens who pay for all of the costs associated with their cell phones send sexually suggestive images via text; just 3% of teens who do not pay for, or only pay for a portion of the cost of the cell phone send these images.

Further details about “sexting” via cell phones may be found in our recent Teens and Sexting Report.4

One in three (34%) texting teens ages 16-17 say they have texted while driving. That translates into 26% of all American teens ages 16-17.

- Half (52%) of cell-owning teens ages 16-17 say they have talked on a cell phone while driving. That translates into 43% of all American teens ages 16-17.

- 48% of all teens ages 12-17 say they have been in a car when the driver was texting.

- 40% say they have been in a car when the driver used a cell phone in a way that put themselves or others in danger.

More details about cell phone use among teens and distracted driving maybe found in our earlier report Teens and Distracted Driving.5

New data forthcoming on Latino youth and their communication choices

Forthcoming from the Pew Hispanic Center, a sister project to the Pew Internet Project, is a new report about the ways young Latinos, ages 16 to 25, communicate with each other. This report will contain results based on a national survey of Hispanics conducted in the fall of 2009. Over 1,200 young Latinos were asked about the ways they communicate with each other, whether through text messaging, face-to-face contact, email or social network sites. This new forthcoming report is a follow-up to the report “Between Two Worlds: How Young Latinos Come of Age in America,” and will be available online at https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic