Overview

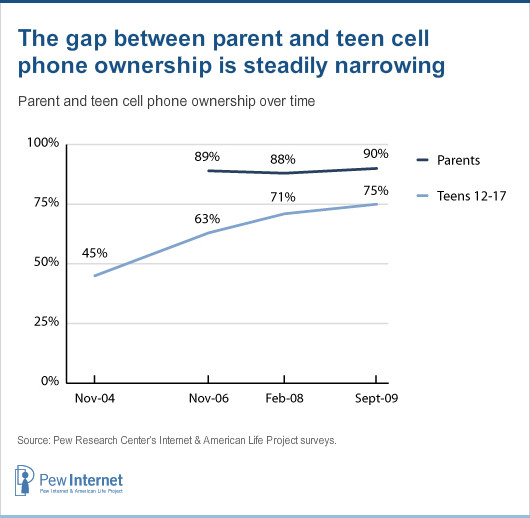

Cell phones are now well integrated into the lives of American teens and their families.28 As of September 2009, 75% of American teens ages 12-17 have a cell phone, a number that has steadily increased from 45% of teens in November 2004. Fully 90% of parents of teens ages 12-17 have a cell phone, a percentage that has remained steady since 2006. Cell phones have become increasingly important modes for intra-family and external communication. For families reached for this survey on a landline who have both cell phones and a landline in their lives, one-quarter (23%) of parents report that they receive all or almost all of their calls on a cell phone, and another half of parents (54%) say that they receive some of their calls on a cell phone and some of them on a landline phone. In total, 8% of American families with teens ages 12-17 in the household do not have a landline telephone at all. And 29% of all families with teens received all or almost all of their calls on a cellular phone.

Who uses cell phones?

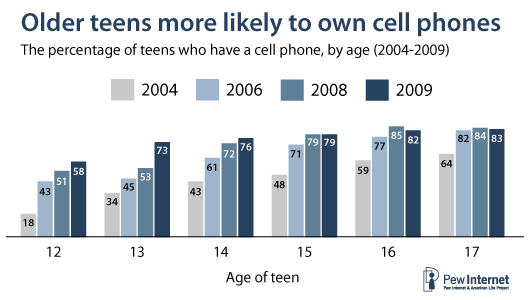

Age has consistently been one of the most important factors in predicting cell phone use. Younger teens, particularly 12 year-olds, are less likely than other teens to have a cell phone. As of September 2009, 58% of 12 year-olds have a cell phone, compared with 73% of 13 year-olds. Looking at the oldest teens in our sample, fully 83% of 17 year-olds have a mobile phone. Over the past five years, ownership of cell phones has been percolating down to ever younger teens. In 2004, just 18% of 12 year-olds had a cell phone of their own, and now 58% of them do. In the same 2004 survey, 68% of 17 year-olds had a phone, and now 83% do. Much of the recent overall growth in cell phone ownership among teens has been driven by uptake among the youngest teens.

Cell phones are nearly ubiquitous in the lives of teens today, with ownership cutting across demographic groups. As both boys and girls move into the latter part of middle school and into high school their world is expanding socially and geographically. Many begin driving, with the consequent need for greater coordination, and expansion of their social lives with texting the conduit for that growth. Texting is also an element of teen identity. More than with other age groups,29 teens have adopted texting into their daily routines and into their expectations of how they can reach one another. Texting is a technology that fills a vital communications niche in teens’ lives.30

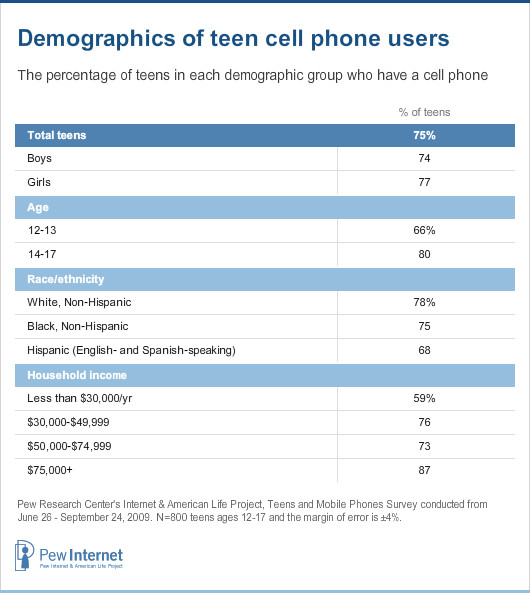

Beyond age, there are few differences in cell phone ownership between groups of teens. Boys and girls are just as likely to have a phone, though they do not always use it in the same way. There are no differences by race or ethnicity in phone ownership by teens. However, socioeconomic status is one area where cell phone ownership rates do vary significantly – with teens from lower income families less likely to own a mobile phone. A bit more than half (59%) of teens in households earning less than $30,000 annually have a cell phone, while more than three-quarters of teens from wealthier families own one.

Ownership of mobile phones is not always a one person, one phone relationship.

[have multiple phones]

One-quarter of teens do not currently have a cell phone, but many have owned one in the past.

Cell phone ownership among teens is also somewhat fluid. Not every teen has a cell phone or has consistent access to one. Among the 25% of 12-to-17 year-olds who do not currently have a cell phone, 34% have had a cell phone at some point in the past. That fluidity is particularly common in the lowest income households; 42% of teens without cell phones in low income households (those with yearly incomes below $30,000) say they have had one in the past.

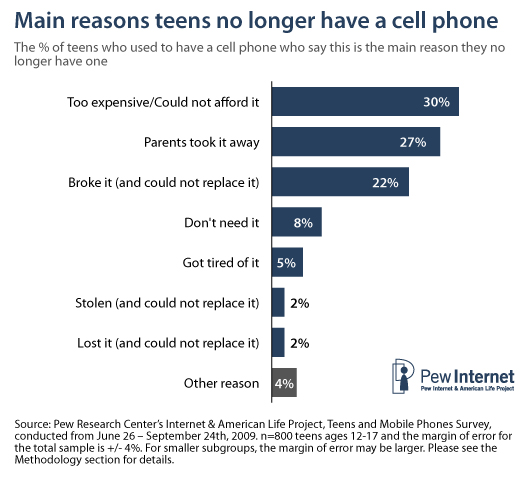

Asked why they no longer have a cell phone, very few teens say they go without a cell phone by choice. Rather, they typically no longer have a phone because it is too expensive, their parents took it away, or it was broken and they could not replace it.

Asked whether they would like to have a cell phone, the majority (69%) of teens currently without cell phones say yes. However, almost a third (30%) say they are not interested in having one. Among teens without cell phones, those whose parent has a cell phone are much more likely than other teens (77% vs. 46%) to say they are interested in having one. There are no significant differences between teen boys and girls, or older and younger teens, where desire for a cell phone is concerned. Teens who have had a cell phone in the past are not significantly more likely than those who have never had one to express a desire for a cell phone.

Phone sharing among teens: Regardless of cell phone ownership, roughly one-quarter of teens say they share a phone with someone else

Sharing phones is a fairly common practice among teens, and roughly one-quarter (23%) of those who do not own their own cell phone share one with someone else. Much of this phone sharing is with others in the household, including siblings and parents. In fact, teens who have a parent with a cell phone are more than twice as likely as those whose parent does not (27% vs. 12%) to report that they share a phone with someone else.

[Name,]

Parents and cell phones

Parent cell phone ownership follows a similar pattern to teens: Parents with lower levels of household income and education are less likely to have a cell phone than parents from wealthier backgrounds. Parents with lower incomes – under $30,000 annually – and lower education levels are less likely to have a cell phone. While 77% of parents earning less than $30,000 in household income had cell phones, 95% of parents who earn more than that have one. Just under three-quarters (73%) of parents without a high school diploma have a cell phone, while more than 92% of parents with greater levels of education have a cell phone. Parents’ phone ownership also varies by race and ethnicity. White parents are more likely than African-American parents to have cell phone, with 91% of white parents owning a phone compared with 83% of African-American parents. Teens whose parents have a cell phone are much more likely to own a phone than teens whose parents do not have one. Four in five teens (80%) with phones have a parent with a cell phone compared with just 38% of teens whose parent did not have a phone.

The economics of cell phones: Plan types and who pays

The ways in which teens and their parents use the cell phone are influenced by a variety of factors. One major influence has to do with the economics of the cell phone – who pays for the costs associated with the cell phone and its use and what are the limitations on the service plan for the phone? Does the user have unlimited minutes to talk or the ability to share minutes? Does he or she have an unlimited or pay-as-you-go text messaging plan? And regardless of who pays, what type of plan does the teen have? A shared family plan, an individual plan with a contract, or a contract-less pre-paid phone? Each of these variations can influence how teens and adults use their mobile phones.

Plan types: Most teens have family plans paid by parents.

Cell phone owners have usage plans for their phones that can be divided broadly into three types. First is a plan that has an ongoing contract to cover a single phone and requires a monthly fee each month until the terms of the contract have been met (often one or two years). A second type of plan is also an ongoing contract, but one that covers multiple people and multiple phones. This is often called a family plan. In these types of plans, members covered under the same contract often have a certain number of voice minutes and text messages that they share. A third type of plan is a pre-paid plan. These plans usually cover one phone. They do not require a long-term contract. Some have a monthly flat fee for the service and others allow the user to add minutes and messages to an account as needed, with the minutes and/or texts debiting as they are used.

Most teen cell phone users (69%) have a phone that is part of a contract covering all of their family’s cell phones. About one in five teen cell phone users (18%) are part of a prepaid or pay-as-you-go plan, and just one in ten (10%) have their own individual contract.

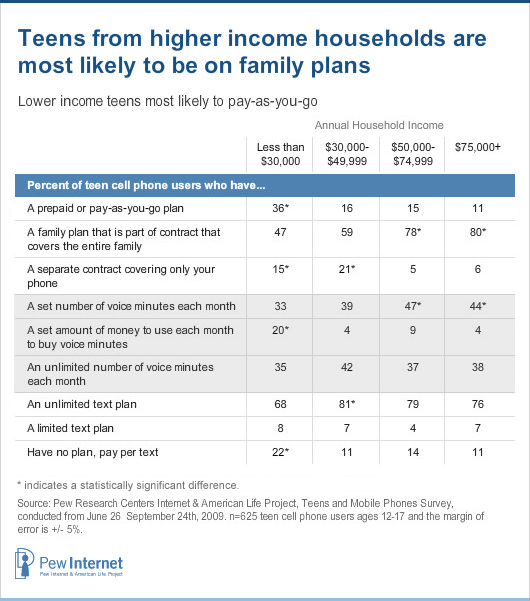

The type of cell phone plan a teen has is significantly related to household income. Teens from lower income households are more likely to use prepaid plans or to have their own contract, while teen cell phone users in households with incomes of $50,000 or greater are most likely to be part of a family plan.

Voice Minutes: the most common combination is a family plan with limited voice minutes.

Nearly all cell phone users have voice minutes of some kind on their phone, but how many they have and how they acquire them varies from plan to plan. Some users have an unlimited number of minutes for talking, usually paid for with a flat fee per month. Other users have a set number of minutes that they have available to them per month, as a part of a monthly contract or fee. Others share minutes with other cell phone users, generally through a family plan. And some users purchase minutes on an as-needed basis, and so may have different amounts of minutes available at different times, based on available funds.

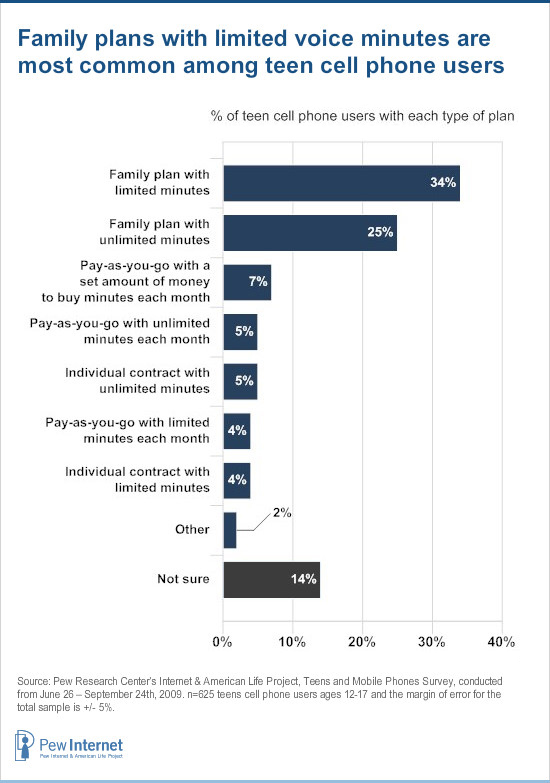

Voice minutes and type of plan (pre-paid, family or separate contract) are closely related. Most teens on a prepaid plan say they have a set amount of money to buy minutes, while most on the family plan say they have a set number of minutes they can use each month. For those teens with their own contract, it is most common to have an unlimited number of minutes each month.

As the above table shows, household income is also a key determinant of the type and amount of voice calling minutes a teen has. Higher income teens (those living in households with incomes of at least $50,000) are more likely than teens in lower income households to say they have a set number of minutes they can use each month. The lowest income teen cell phone users (those from households with incomes below $30,000 annually) are four times as likely as other teens to say they have a set amount of money with which to buy minutes each month.

How minutes are managed within a cell plan varies by race and ethnicity. Almost half of all white teen cell phone users (47%) say they have a set number of minutes they can use each month, compared with just 15% of black teen cell phone users. Black teens, in contrast, are more likely than white teens to say they have a set amount of money to spend each month to buy minutes – this is true for one in five black teen cell phone users overall (20%), and just under half (42%) of black teen cell phone users in households with incomes below $30,000. Still, most black teen cell phone users (44%) say they have an unlimited number of minutes to use each month.

Voice minutes also vary by age, with older teens (ages 14-17) more likely than younger teens (ages 12-13) to have a set number of minutes they can spend each month (51% vs. 40%). Young girls are the most likely to have unlimited voice minutes on their cell phones: 57% of 12-13 year-old girls have unlimited voice minutes. (All of the above figures are based only on teens who know how many voice minutes they have – 13% of teens are not sure how their plan works and could not answer the voice minutes question.)

When one combines type of plan with voice minutes, the most common combination is a family plan with limited voice minutes – one in three teen cell phone users (34%) are on this type of plan. One in four teen cell phone users (25%) are on a family plan with unlimited minutes. A younger high school boy explains his family’s plan:

- Minutes are more expensive than the texting, so I have unlimited texting for 10 dollars, but the minutes are like 40, so we just share those. She kept warning me before, um, she got me T-Mobile and if I went over the minutes she’d take my phone, but I never went over my minutes.

Texting plans: The bulk of teens have unlimited text messaging plans.

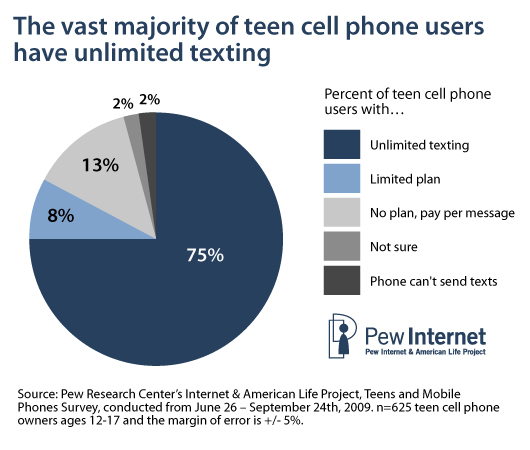

The economics of texting have radically shifted in recent years and that has likely contributed to the increased popularity of texting among teens. Over the past few years, unlimited texting plans have become the norm among teen text users. Three in four teen cell phone users (75%) have unlimited texting plans. Just 13% of teen cell phone users pay per message. This high rate of unlimited texting holds fairly steady across different income categories and racial/ethnic groups. Only among white teens is there a strong correlation between household income and having unlimited texting. Just 59% of white teen cell phone users in households with incomes below $30,000 have an unlimited text plan, compared with 79% of all other white teen cell phone users. As one would expect, texting availability varies by plan type. Teens on family (81%) and individual (78%) plans are significantly more likely to have unlimited texting than those with prepaid plans (54%). The percentage of teen cell phone users with unlimited texting rises steadily with age, and more girls than boys report having plans with this feature. The group most likely to have unlimited texting is 14-17 year-old girls, 86% of whom have this feature in their plans.

In this context it is worth noting that the cost for sending and receiving text messages without a subscription can range between 15 to 30 cents per message.31 On the other hand, unlimited subscriptions are extremely common. Thus, if teen A has an unlimited texting subscription and communicates with teen B who does not, texting would represent a significant burden given that U.S. cell phone owners pay to both send and receive text messages. This situation would encourage teen B to get a bundled or unlimited texting subscription. This type of calculation would ripple thorough groups of teens who, as we will see below, have started to use texting for many different purposes. Those who do not sign up for specific subscriptions face the possibility of having to pay dearly for the use of texting by their friends with unlimited plans.

Who pays for teens’ cell phones?

Twenty-nine percent of teen cell phone users pay for at least some of the costs of their cell phones; that figure rises to 63% among black and Hispanic teens in households with incomes below $30,000.

Seventeen seems to be a critical age in terms of cell phone responsibility; at that age the percentage of cell phone users who are responsible for at least part of their cell phone bills jumps to 40%. One in five 17 year-olds (20%) pay their entire bill themselves. For those teens who do not pay entirely for their own cell phone bills, 94% say it is their parents who pick up the bill.

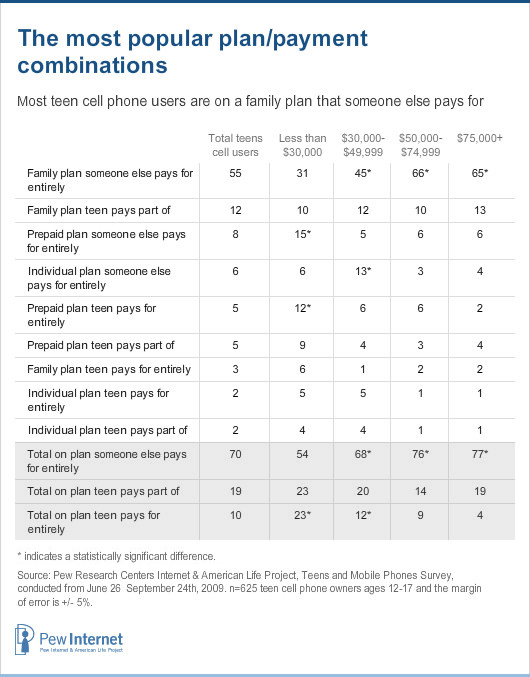

Overall, over half of all teen cell phone users are on family plans that someone else (almost always a parent) pays entirely—this figure jumps to two-thirds among teens living in households with incomes of $50,000 or more. Other popular subscription types are those family plans for which the teen pays some of the costs and someone else pays the remainder. Prepaid or pay-as-you-go plans for which someone else pays are also common.

Among teens living in households with incomes below $30,000, only 31% are on a family plan that someone else pays for. In this group, 15% have prepaid plans that someone else pays for, and 12% have prepaid plans that they pay for entirely themselves. Black teens living in low income households are the most likely to have prepaid plans that they pay for themselves.

How the economics of mobile phones affects teens’ cell use

Teens who pay for their own phones use the phone in a wider range of ways.

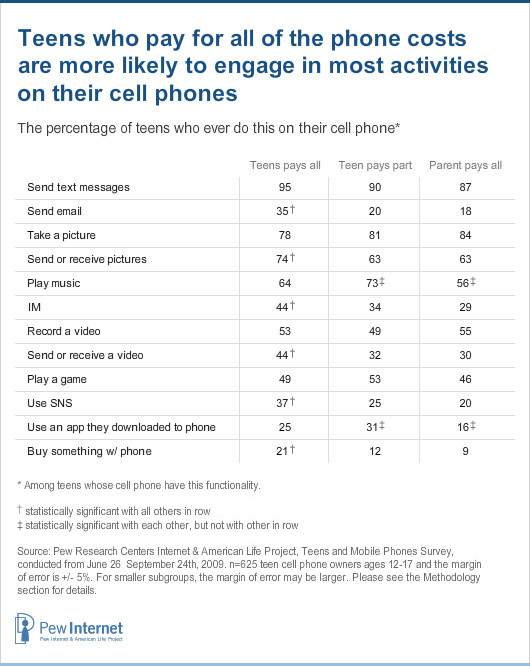

Teens who pay for the full cost of their cell phones do more on and with their phones. Those teens who have parents who pay for at least part of their phone engage in a more limited number of activities on their phones. While almost all teens use their phones to text, teens who pay the entire cost of ownership for their cell phones send more texts and do so more frequently throughout the day. Three-quarters (73%) of teens who pay for their own phone say they send text messages several times a day, compared with 65% of teens whose parents pay for their phone and 55% of teens who pay for part of their phone. In addition to texting frequently, teens who pay for their own phones are more likely to send email and instant messages on their phone, and are more likely to send, receive and record videos than other teens with cell phones that are fully or partially paid for by others. They are also more likely to use social network sites on their mobile phone, and to send and receive photos. Teens who pay for their own phones are also more likely to buy things online via the cell phone.

Teens who pay part of the cost of their cell phone are the most likely to play music on their phone and more likely than teens whose parents cover the cost of phone ownership to install applications on their phones.

Teens whose phone use is fully paid by someone else are more likely than other teens to take photos with their phones, though not necessarily any more likely to share those photos with others via their handset.

All teens are equally likely to play games on their phone regardless of how their phone costs are covered. Many games are pre-loaded on cell phone handsets and do not require additional or on-going costs to play. Another subset of games may be downloaded to a cell phone, but often result in charges or costs to the phone owner.

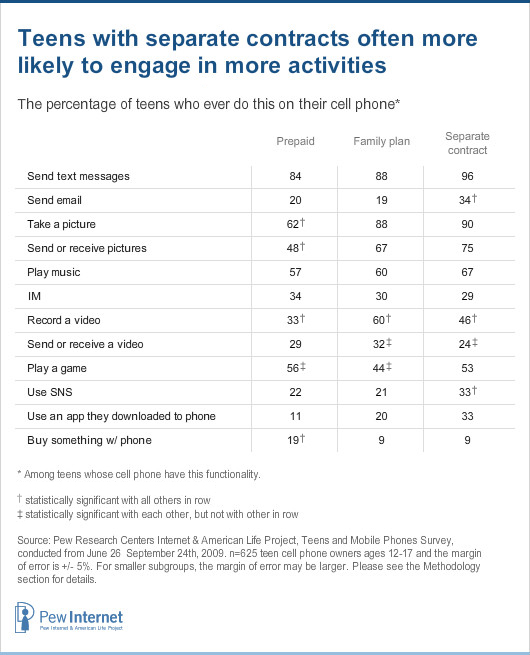

Teens on pre-paid plans are less likely to use many cell phone functions.

All teens, regardless of phone plan, are just as likely to send text messages, instant messages or play music on their phone. However, teens on pre-paid plans are less likely than teens with other plan types to engage in almost all other kinds of activities with their handsets. With the exception of being more likely to use their phone to buy a product or service than other users, teens on pre-paid plans are less likely to take, send or receive photos, record videos or download and use an app for their phone.

Teens with family plans are more likely than other phone owners to record and exchange videos, and are a bit less likely than pre-paid plan users to play games on their phone. They are less likely than teens with a separate phone contract to access a social network site or use a downloaded app on their phones. Otherwise, family plan users tend to be the most middle-of-the road users of the available functions of their phones.

Teens with a separate contract for their phone are more likely than other teens to use their phones to send and receive email, visit a social network site or use a downloaded app on their phones. They are also more likely than teens with prepaid plans to take and share photos and record videos, but are less likely to have bought something using their phone.

Teens on metered plans are less likely to take advantage of cell phone add-ons, except music.

Among different types of voice or text messaging plans, teens with the most “metered” plans – plans where minutes or texts must be paid for individually – generally have the most constrained and limited use of their handsets. Just half of teens who say they must pay per message for texts send them. That compares with 95% or more of teens with unlimited or bulk texting plans who are texters. But beyond text messaging, teens with metered plans for voice or text are less likely than their peers to use multimedia tools like photos or video on their phones, and less likely to access an online social network. The only exception is music – teens on metered plans are just as likely and sometimes more likely to play music on their phones than teens with other types of plans.