Introduction

This chapter addresses the new roles that cell phones play in the communication patterns of teens. The chapter is broken into four parts that analyze: 1) the role of texting in teens’ lives; 2) the role of cell voice calling in teens’ lives; 3) the way texting and cell voice calling fit into the larger scheme of teen communication patterns; and 4) the other activities that teens perform on their ever-more-sophisticated handheld devices.

Part 1: Text messaging explodes as teens embrace it as a vital form of daily communication with friends.

[the cell phone]

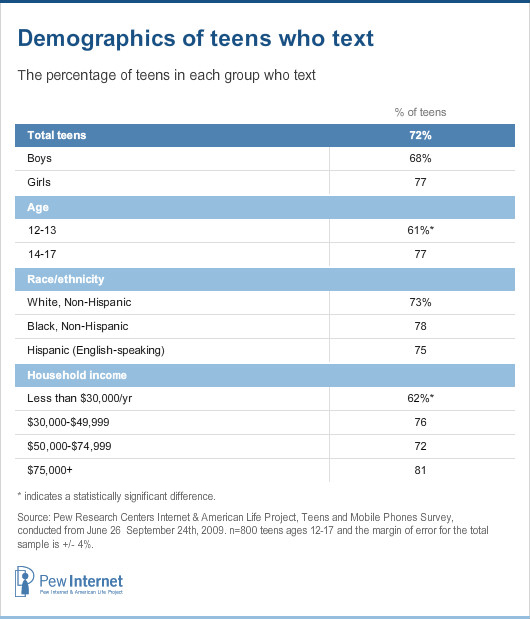

Text messaging frequency increases as teens age – 35% of 12 year-olds say they text daily, while 54% of 14 year-olds and 70% of 17 year-olds text everyday. Younger teens are much more likely to say that they never send or receive text messages – 46% of 12 year-olds do not text; only 17% of 17 year-olds do not text. Girls are more likely to text than boys with 77% of all girls texting while 68% of boys do. Older girls ages 14-17 are the most avid texters – 69% say they text their friends every day, while 53% of boys the same age report daily texting.

Lower income teens are more likely to say that they never send text messages, and higher income teens are slightly more likely to say they send and receive texts every day. Nearly 2 in 5 teens whose families earn less than $30,000 annually say they never use text messaging, compared with just 20% of teens from families earning more than $75,000 per year. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of all teens from households earning more than $75,000 annually text every day, while 43% of teens from families that earn less than $30,000 text daily.

Given how vital a mode of communication texting is for teens, it is unsurprising that parents have stepped into the realm of texting a bit more deeply than other adults as a way of keeping the lines of communication open with their child. More than 7 in 10 (71%) of cell-phone owning parents of teens 12-17 say they send and receive text messages on their cell phones. In comparison, 65% of all adults 18 and older send or receive text messages.39

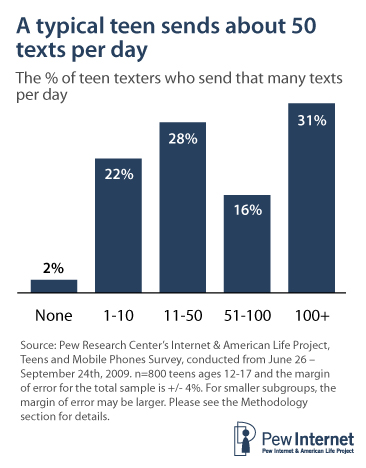

The typical American teen who texts sends 1500 texts a month.

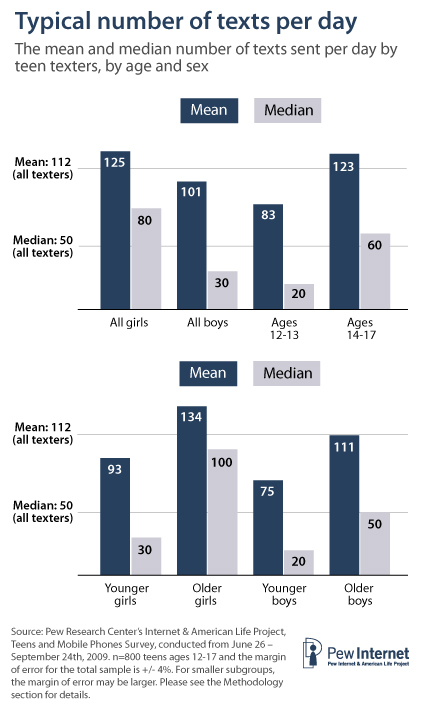

Given the frequency with which teens text, it follows that they would be sending and receiving a very large number of text messages and the data bear this out. The typical text messaging teen sends and receives 50 texts a day, or 1500 text messages a month. Girls text more than boys do; girls who text typically send and receive 80 texts a day, boys send and receive 30. Older teens text more than younger ones: Teens ages 12-13 who text send and receive 20 texts a day, while high school-age teens typically send and receive 60 text messages a day. Older girls are the most active texters, with 14-17 year-old girls typically sending and receiving 100 text messages a day, or more than 3000 texts a month. In general, a little more than one-fifth of teens who text (22%) send and receive between 1-10 texts a day (i.e. 30 to 300 a month). Younger boys are the most likely to text in this manner. At the other end of the scale, about 14% of teens send between 100-200 texts a day, or between 3000 and 6000 text messages a month. Another 14% of teens send more than 200 text messages a day – or more than 6000 texts a month. In light of these findings, it is not surprising that three-quarters of teens (75%) have an unlimited text messaging plan.

There are also some differences in text messaging by race and ethnicity. While white texting teens typically send and receive 50 texts a day, black teens who text typically send and receive 60 texts and English-speaking Hispanic teens send and receive just 35. The mean number of text messages are similar for these groups (whites average 111 texts a day, blacks 117, and Hispanics 112), suggesting that black teens have a slightly higher baseline level of texting than whites or Hispanics. There are no significant socio-economic differences in the average numbers of texts sent a day by teens in different groups. As one high school girl explained: “My parents will kind of joke about it. I think my last phone’s bill had like altogether 3,000 text messages and they were like, ‘How do you even do that?’ That’s not that bad. But I don’t think it’s too big of an issue. They wouldn’t actually get mad about it since it’s unlimited.”

Teens, particularly girls, text friends several times a day.

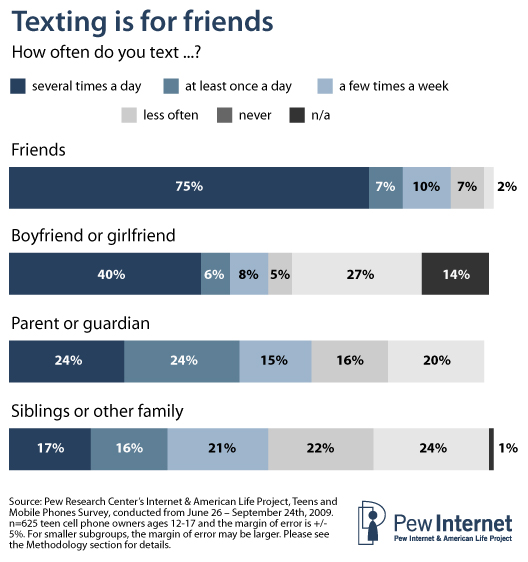

Who are teens texting? The data show that 81% of teens who text are texting with their friends at least once every day. Significant others are also major daily texting partners — 46% of teens who have a boyfriend or girlfriend send or receive texts every day with their significant other. Teens also report texting their parents or guardians as well as their siblings. Our analysis shows that 48% text with their parents at least once a day and 33% of those who have siblings text with them on a daily basis.

Looking at the other end of the scale, only 2% of teens who text never send or receive messages from their friends. This points to the central role of texting among friendship groups. But texting may not be as vital for some in maintaining familial relationships, as 20% of teens who text say they never text a parent and 24% never text siblings or other family members. Interestingly, the analysis also shows that 27% of cell phone-owning teens with a boyfriend or girlfriend never send or receive texts from them.

In keeping with their greater overall levels of interpersonal communication, girls and high school-age teens (ages 14-17) are much more likely than boys or younger teens to interact frequently via text messaging with friends and siblings. Fully 86% of girls – and 79% of teens 14-17 – say they text friends several times a day, compared with 64% of boys and younger teens who text friends with that frequency. The data show that 35% of younger teen boys (aged 12 – 13) said that they texted friends on a daily basis. This compares with 44% of teen girls of the same age, 53% of the older teen boys (aged 14 – 17) and 69% of the older teen girls who said that they texted to their friends on a daily basis. The mirror image of the same pattern is seen among teens who say that they never text with friends. The data show that 40% of the youngest teen boys, 36% of the youngest girls, 28% of the older teen boys and 17% of the oldest girls said that they never text friends.

This gender trend is reflected in comments from the focus groups about how and how often boys and girls text. As one younger high school-aged boy explained, “You’ll still text your boys, but, at the same time you don’t want to be sitting there going back and forth hours on end just about gossiping or whatever. It’s just not, it’s not the way they do it, I guess.” In fact, several respondents explained how girls tend to be more avid texters, not only in terms of frequency of messages, but also with their use of language, punctuation, and emoticons. Another boy commented, “Girls text really weird, like the spelling. It’s all like dollar signs. A lot of exclamation marks.” Boys, on the other hand, are less prone to use emoticons and other indictors of tone in their (oftentimes brief) messages. Other research has also shown that teen girls are more prolific in their use of texting than teen boys.40

The type of cell phone plan a teen has seems to have a relationship to how often teens text their friends. Four in five (80%) cell phone users with an unlimited texting plan texted to friends on a daily basis. Significantly fewer teens with a limited texting plan texted this often (55%) and only 18% of those who did not have a texting plan use the service to contact friends daily.

Half of texting teens send messages to parents every day.

Most teens text their parents at about the same rates, with about 50% of teens saying they text their parents at least once a day. At the same time, girls and older teens are more likely to text brothers, sisters and other family members than boys and younger teens. One in five girls (20%) and 19% of teens ages 14-17 text their siblings several times a day, while 13% of boys and 11% of middle school-age teens text siblings with that frequency.

African-American teens are more likely to report frequently texting siblings or other family, as well as significant others. Three in ten (30%) African-American teens say they text brothers, sisters or other family members several times a day, compared with 14% of white teens and 19% of English-speaking Hispanic teens. Similarly, more than half (53%) of texting African-American teens say they text their boyfriends or girlfriends several times a day, compared with 37% of white teens and 45% of Hispanic teens. Teens ages 14-17 are somewhat more likely to text a boyfriend or girlfriend several times a day than younger teens (45% vs. 27%), but much of this variation is mostly like due to a greater likelihood of older teens having a significant other.

Why teens text

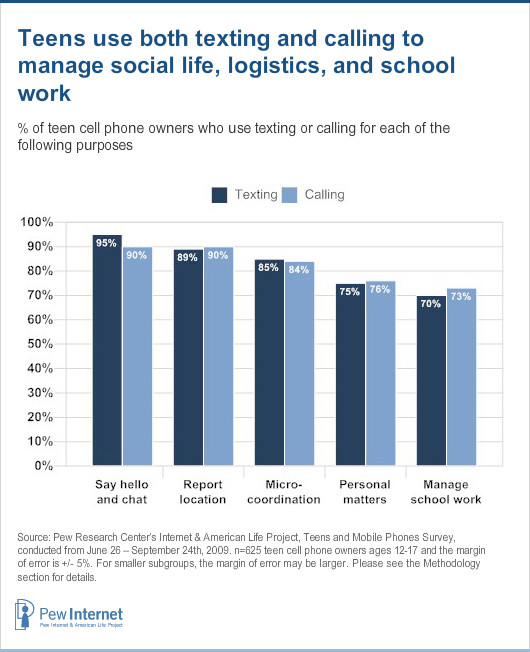

Texting can be used for a myriad of reasons and this study focuses on a handful of dimensions that roughly organize the ways in which teens can communicate with friends and family. Teens were asked about texts that support and maintain relationships and about texts used to coordinate meetings and to report locations. We also asked about texts sent as a way to exchange information privately in situations where voice calling would be inappropriate or unwise. Finally, teens were asked about how text messaging is used as a part of school work done outside of school.

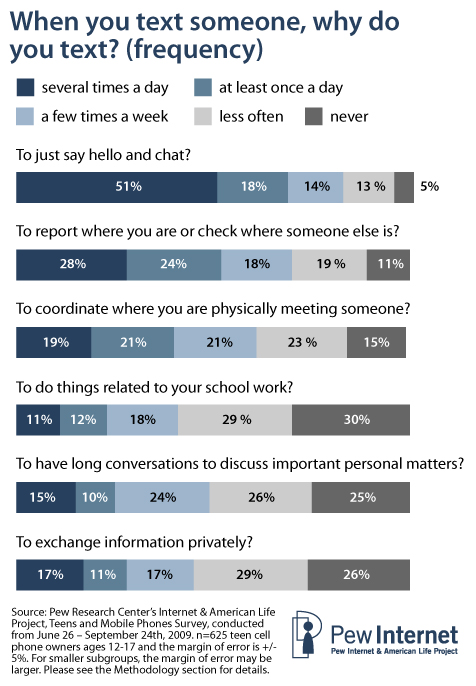

In the Pew Internet Project survey, the most frequently given reason why teens send and receive text messages is to “just say hello and chat.” More than nine in ten teens (96%) say that they at least occasionally text just to say hello, and more than half (51%) say they do this several times a day. A younger high school boy in our focus groups describes his text messaging: “I think it’s basically just chatting. It’s small talk. How are you doing? What’s up?” The vast majority of teens also say they use text messaging to report where they are or to check in on where someone else is, with 89% of text-using teens reporting this. More than a quarter of texting teens say they check in several times a day and another quarter do it at least once a day.

Three-quarters of texting teens use text messaging to exchange information privately – with more than a quarter doing this daily or several times a day. Another three-quarters of text-using teens also say they have long message exchanges by text to discuss important personal matters. One-quarter of teens (25%) report having long personal text exchanges at least once a day. A high school-age girl in our focus groups talks about some of the positives and drawbacks around lengthy, personal exchanges on the phone:

- I like that you stay connected easily and stuff and I text a lot, but I feel like texting is kind of impersonal and its not the same as face to face conversation and texting takes a lot longer to say what you want to, so if you are texting someone for a while, you are like, ‘Oh, man, we’ve been texting for like two hours,’ when in reality if you were having like a conversation, it would be like a ten minute conversation. So you feel like it is a more in-depth conversation than it really is. It’s kind of like a false sense of communication I guess.

Texting is also a method for managing school work – 70% of teens have used text messaging to do things related to school work, with 23% of teens texting for school at least once a day.

On-the-go micro-coordination41 is another frequently cited reason for texting: 40% of teens who text say they do this at least once a day and often more, and 84% of teens say they use text messaging in this way. Cell-phone owning teens who have parents who also have phones are more likely to report using text messages to coordinate physical meetings – 42% of parents with cell phones have a teen who reports micro-coordination of in-person meetings at least once a day, compared with 28% of teens with parents who do not have cell phones.

Teens from lower income families earning less than $30,000 annually are less likely than wealthier teens to use text messaging for school work. Close to half (45%) of poorer teens say they never text about school work, while 30% of all teens say they never text about school assignments.

Older teens are more likely to text for a variety of reasons than younger teens. While teens of all ages pick up the phone to say hello and chat with friends, younger teens are less likely to check in with someone to find where they are (81% vs. 91% of teens 14-17) or to coordinate meeting someone – 78% of 12-13 year-olds compared with 87% of 14-17 year-olds. This difference is most likely attributable at least in part to the greater mobility of older teens. Older teens are also more likely than younger teens to do things related to school work with text messages, to have long exchanges about important personal matters and to text in order to exchange information privately.

Girls are more likely to use texting for social connection.

While both sexes are likely to send text messages to coordinate meetings or to check in with others, girls are more likely to use texting for socially connecting with others – either just to say hello and chat (59% of girls do this several times a day compared with 42% of boys) or to have long text changes on important personal matters (84% of girls do this, as do 67% of boys). Girls are also more likely than boys to text about school work (77% vs. 62%) and to text to keep the content of messages private (79% vs. 68%).

There are few racial or ethnic differences in reasons why teens use a cell phone. Black teens are less likely than white or English-speaking Hispanic teens to report where they are or to check in to find out where someone else is (90% of white and English-speaking Hispanic teens report their location, while 79% of black teens do). English-speaking Hispanic teens are less likely than white teens (64% vs. 77%) to say they text message to exchange information privately.

Teens with pre-paid plans are less likely to use text messaging to report their whereabouts.

The phone plan that a teen has also matters in how they use their phones. Teens with prepaid phone plans are less likely to use their phone to text for certain reasons. While all teens, regardless of plan, are likely to text to say hello, to have long text exchanges or to text about school work, teens with prepaid plans are less likely than teens with family plans to check in with others or to report their locations to someone else.

[group is laughing]

Part 2: The state of voice calling on the cell phone.

While texting is the most common use of the cell phone among teens, talking on the device is also a central function. Voice interaction provides teens with access to friends and parents. The convenience of the cell phone means that they are never out of touch. This is both a positive and a negative thing in the eyes of the teens. As one younger high school-age boy said:

- The best thing [with the cell phone] is that it’s so convenient and you can just talk to people all the time, and like even if you’re not at home. And like, the worst thing is like, when people keep calling you or like, it just gets annoying.

Girls are more likely than boys to call friends every day.

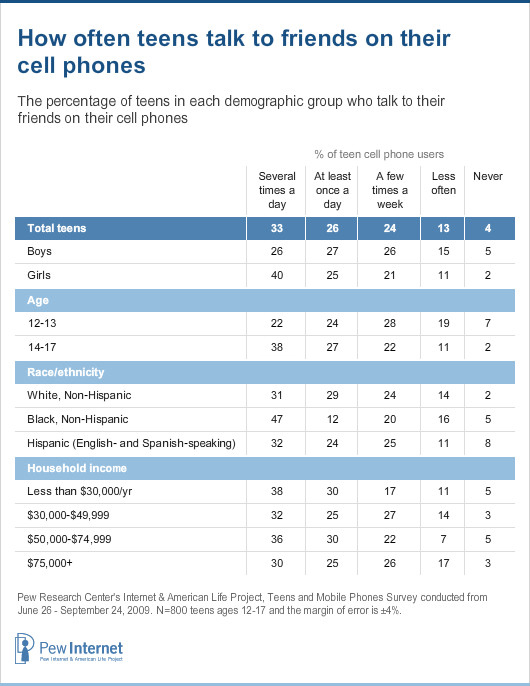

Almost all teens with cell phones (94%) say they use the phone to talk to their friends, and half of teens (50%) say they do this every day. Once again, girls are more substantial communicators – 59% of girls with cell phones talk to their friends on their mobile every day, while 42% of boys with cell phones call friends each day. High school-age teens are also more likely than middle school-age teens to talk on their cell phone with friends daily – 56% of high schoolers talk daily on their cell phone, as do 35% of middle schoolers.

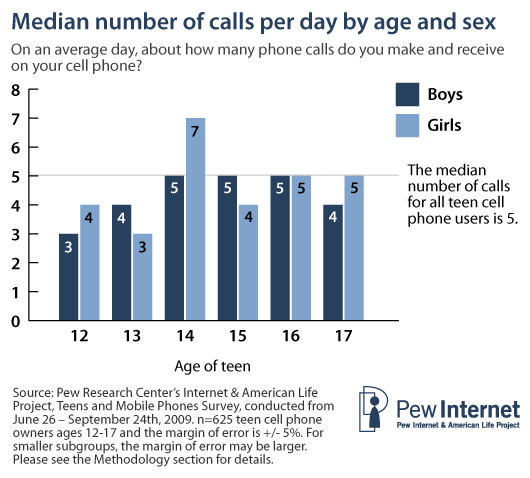

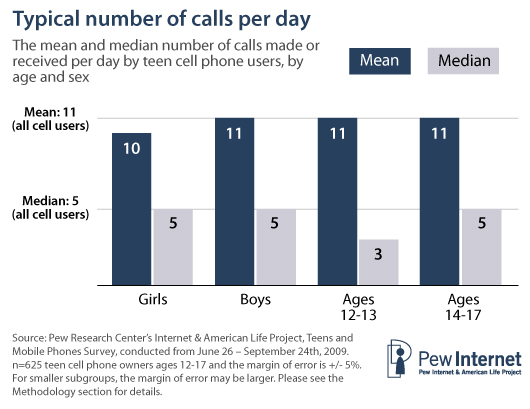

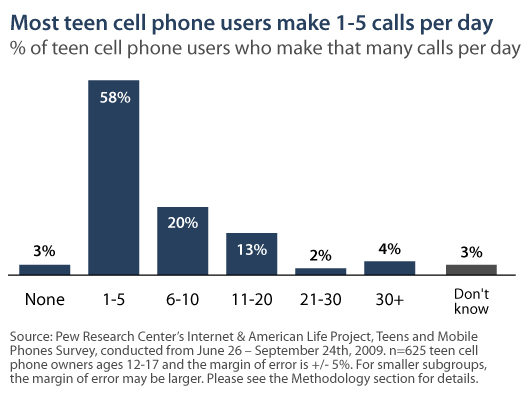

The youngest teen boys ages 12-13 are more likely than other groups to say that on an average day they make no calls on their cell phone, with 9% of those boys reporting no calls, while just 2% of all other teens report making no calls on their phone on a typical day. Overall, there is no difference by gender or age in the average number of calls made a day by teens – teens average42 just under 11 calls a day, with a median of 5 calls per day. The only variance in the median is among younger teens ages 12-13 who typically make or receive 3 calls per day.

There are notable differences in the number of calls made on a typical day by race and ethnicity. White teens make fewer calls a day than either black or English-speaking Hispanic teens. White teens typically make 4 calls a day, or around 120 calls a month, while black teens make 7 calls a day, or about 210 calls a month, and Hispanic teens make 5 calls a day, or about 150 calls a month. When looking at the mean number of calls per day by race/ethnicity (7 for whites, 13 for blacks and 17 for Hispanics), it’s clear that a larger portion of the very heavy callers are found in the black and Hispanic populations.

There is an economic consideration associated with the use of voice, as the type of phone plan a teen has also influences the number of calls they make on the average day. Sixty-three percent of those teens with unlimited voice subscriptions reported daily voice calling with friends, while 47% of those who had fixed minute subscriptions and 31% of those who had a set amount of money to spend on voice minutes reported making calls to friends daily. Teens with a fixed number of voice minutes per month typically make 5 calls a day, while teens with a set amount of money to use on minutes make 3 calls a day and teens with unlimited minutes typically make 5 calls a day.43 Whether a teen pays for his phone bill also affects the volume of calling. Teens who pay their entire phone bill themselves make 7 calls on a typical day, while teens who pay part of the cost make 5 calls and teens who pay none of the cost for their cell phone make 4 calls a day. A small portion of teens (10%) who have a cell phone and say they do not text at all also say that they do not make or receive any phone calls in the average day.

Looking for a moment at the teens who own a cell phone but do not use the voice function, the youngest teen boys are over-represented. The data show that 9% of this group report never making a voice call while only 2% of all other teens report the same.

Who teens call

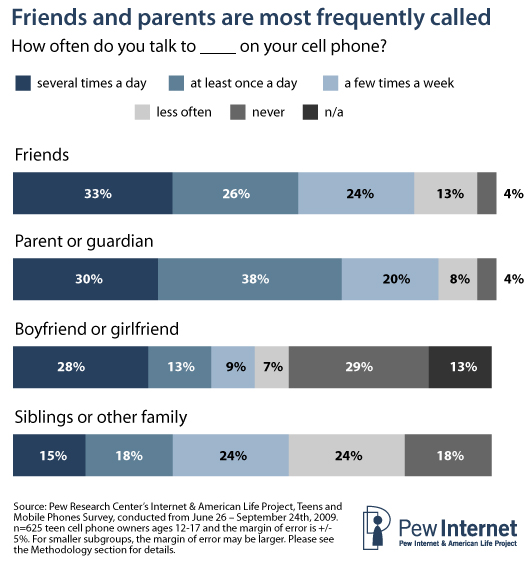

Voice is for parents.

When teens use the phone for calling, they are most likely to be calling parents, with 68% of teens with cell phones saying they talk to their parents on their cell phone at least once a day. Talking with friends is a close second to parents, with 59% of teens with cell phones saying they talk with friends once a day or more often. About half of teens who have a boyfriend or girlfriend call them on a daily basis. Brothers, sisters and other family members are the least likely to be called on daily basis, with just about a third of teens who have siblings (33%) saying they talk at least once day. As with texting, only 4% of teens report never calling their friends. Interestingly, while 20% report never texting their parents, only 4% of teens with cell phones say that they never call their parents or guardians. Thus while intergenerational texting is not necessarily uncommon, voice interaction between parent and child via the mobile phone is substantially more common.

Girls talk more frequently with friends on their cell phones than boys.

[a different school]

Older teens with phones are also more likely to talk to friends on their cell phones frequently. Nearly 2 in 5 (38%) teens ages 14-17 with cell phones talk to friends several times a day while 22% of younger teens say the same. Older teens are also more likely to talk with siblings, other family and significant others multiple times during the day. The latter is partly due to the fact that older teens are more likely to have a significant other than younger teens.

Black teens with cell phones are more likely than whites to say that they talk to friends and siblings on the phone several times a day. White teens are more likely to say they talk to friends once a day, and to their siblings and other relatives infrequently – once a week or less often. There are no differences by gender, age or race in the frequency of talking to parents on a cell phone.

As we have seen in previous research, communicating frequently in one mode is often related to communicating frequently in multiple ways.44 Talking and texting on the cell phone are no exception – teens who text are more likely to say they talk frequently with almost everyone – friends, parents and significant others – several times a day. The exception is in the case of siblings, where texters are more likely to talk with them by cell phone once a day.

Similar to text messaging, the type of cell phone plan a teen has relates to how frequently she talks on the phone. Perhaps surprisingly, teens who have an unlimited texting plan are more likely to talk on the phone more frequently with everyone – friends, family and romantic partners. Less surprisingly, teens with unlimited voice minutes are more likely to talk frequently with friends and boyfriends or girlfriends. However teens on family plans – who share minutes with parents and other family members45 – are more likely to talk to their parents and siblings more frequently. Teens who pay for their cell phone out of their own pockets are much more likely to talk with significant others frequently through the day – 55% of teens who pay for their phones talk with a boyfriend or girlfriend several times a day, compared with 24% of those who partly pay and 26% of those who do not pay their cell phone bill. Of course, it is difficult to disentangle whether these behaviors are what drives users to select certain plans or a result of the plan selected.

The purpose of teens’ calls – signaling your whereabouts.

The purpose of teens’ calls: Signaling your whereabouts.

As was the case with text messaging, teens primarily use their cell calls to report on their location or check where someone else is. Just about half of teens with cell phones (49%) say they use mobile voice calling to report their location or check on someone else every day or more often. A bit more than a third of teens with phones (37%) say they call “just to say hello and chat” every day or more often, and another third (33%) say they place or receive calls to coordinate where they are physically meeting someone everyday or more often. Calls made to discuss school work are also fairly common: 22% do this on at least a daily basis, though 26% say they never call for this reason. Teens also place long voice calls to discuss important personal matters: Some 19% of teen cell users participate in such calls on at least a daily basis, though 36% make these kinds of calls less than a few times a week and 23% report never making this type of call.

Some teens find the purposes for which they use the phone to be quite different from their parents’ use. As one high school boy notes: “The only reason why I usually call my mom is like, if I want to ask her something or if I want to go somewhere. Or, like, what time I need her to come and pick me up. But, she interacts with us like just to see where we at, to be in our business.”

African-American teens use the phone more for social interaction; White and Hispanic teens use their cell phones more often for coordination and location sharing.

There are some variations by race and ethnicity in the frequency with which teens use their cell phones to make or receive calls for these different purposes. Among African-American teens, the phone is their hub for social and personal chats, while white teens and to a lesser extent English-speaking Hispanic teens use the phones more frequently for coordination and location sharing. African-American and Hispanic teens are more likely to use their phones frequently for school work than white teens, who still use it for this purpose, but less often.

Younger boys do not make many voice calls for any purpose.

When looking at age and gender, younger boys make calls less frequently for almost every purpose. Younger boys ages 12-13 rarely just call to say hello and chat; nearly 60% of boys in this age group say they call just to say “hi” a few times a week or less often, and another 14% never do so. Just 7% of boys this age say they make calls just to chat several times a week, compared with 17% of older boys and 21% of girls of any age.

In a counterpoint to the youngest boys, girls are more likely than boys to make calls every day or more often to report on their whereabouts, talk about things related to school work or have long, personal conversations. Similarly, older teens ages 14-17 are more likely to say that at least once a day they coordinate meeting someone or discuss location, and are more likely than younger teens to say that they call to discuss school work or have long personal conversations.

Teens who report primarily using voice calling when talking to a boyfriend or girlfriend are more likely to report frequent (several times a day) voice calling just to catch up and say hi and for long, important conversations than those teens who say they primarily text message with their significant other.

Unlimited plans of all kinds are tied to more varied purposes for voice use.

The economics of a teen’s cell phone plan also relates to how and why they use the phone to make voice calls. Teens with unlimited voice minutes are more likely to make voice calls several times a day for all purposes — coordination, checking in, schoolwork, catching up and long important calls — than are teens with more limited calling. Teens with unlimited texting plans are also frequent users of voice calling for coordination, checking in with someone, school work or long discussions – everything but calling just to say hi. Teens with plans where they have a set amount of money to use on the phone per month are also more likely to say they call people several times a day to say hello and chat.

Part 3: Where text and cell talk fit in teens’ overall communication patterns with friends.

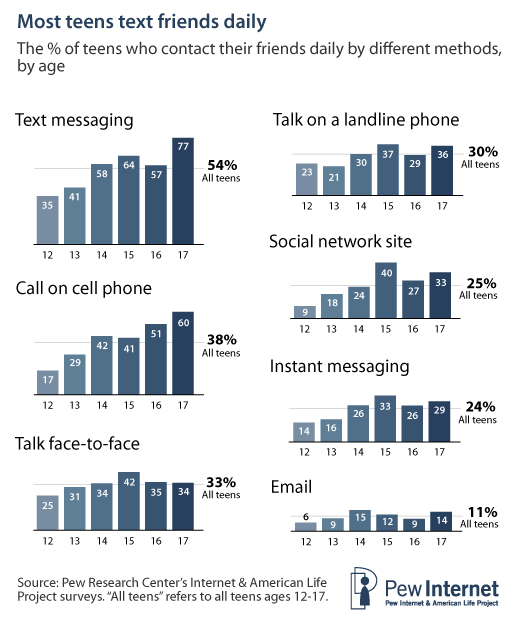

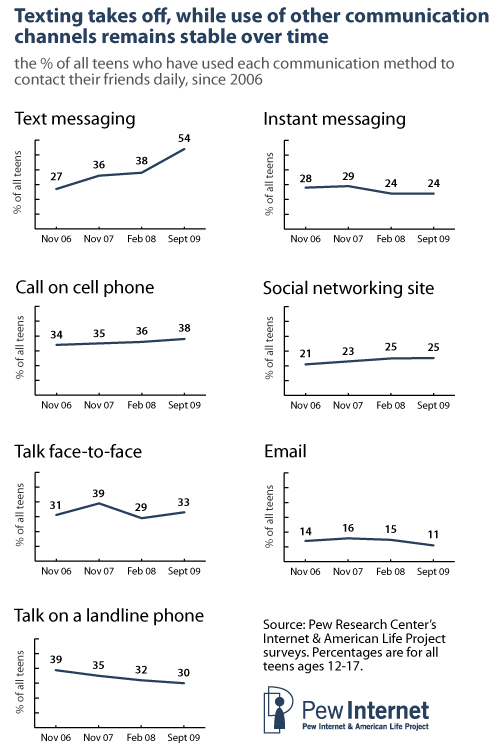

The cell phone’s centrality to teens’ social lives can be most fully appreciated when examined in the context of teens’ communications choices more broadly. In this survey, teens report that when socializing or communicating with friends, texting is the most frequent form of interaction. Indeed, when looking at all teens regardless of their access to either a mobile phone or the internet, 54% report using texting on a daily basis in order to socialize or communicate with friends. Mobile voice is used daily by 38% of teens. Further down the list are interacting with friends face-to-face outside of school (33%), talking on a landline telephone (30%), communicating daily via social network sites (25%), and instant messaging (24%). Email was the least used communication activity, with only 11% reporting that they use it on a daily basis.

It is notable that texting and mobile voice are the most common platforms of communication between friends for all age groups. Communicating through social network sites (SNS), landline, face-to-face and instant messaging (IM) cluster somewhat lower in the ordering of communication methods employed by teens. Email is the least used of these channels. The low placement of face-to-face interaction outside of school time is also of note. This type of interaction is often seen as the “gold standard” of interaction but viewed in this context, it is not the most frequent form of interaction for teens.

Older teens are more frequent users than younger teens of all communication platforms. Relatively speaking, there are only marginal differences between older and younger respondents when looking at face-to-face interaction and email. By contrast, there are wide differences by age when looking at mobile-based communication. About 35% of 12 year-olds use texting on a daily basis. This compares with 77% of 17 year-olds. Among 12 year-olds, 17% used mobile voice to talk with friends while 60% of the 17 year-olds reported the same. The differences between groups for social network sites, instant messaging, and landline telephony were less than with mobile telephony but more than in the case of face-to-face interaction and email.

Looking at the opposite end of the scale, not all teens use all channels, and the type of channel used shifts when comparing the older and the younger teens. In broad strokes, communication platforms fall into two categories: those that are used by teens of all ages and those that have been adopted by older teens but not younger ones. Landline telephony and face-to-face interaction represents the first group: roughly equal numbers of teens in all age groups report using landlines and interacting with friends face-to-face outside of school, though older teens tend do so a bit more frequently than younger teens.

By contrast, many of the younger teens report that they do not use texting to communicate with their friends. While 44% of 12 year-olds say that they do not use texting, only 11% of 17 year-olds report the same. While other material in the survey shows that texting has become a central form of interaction for teens, it is also important to remember that not all U.S. teens are a part of this revolution at the present.

Texting has grown enormously in the past 18 months and is the core of teens’ communication with friends.

Texting is the form of communication that has grown the most for teens during the last four years. The data show that between 2006 and 2009 the percent of teens who use texting to contact friends outside of school on a daily basis has gone from 27% to 54%. Face-to-face contact, instant messaging, mobile voice and social network messaging have remained flat during the same period, while use of email and the landline phone have decreased slightly.

When all forms of communication are taken together, texting emerges as the most common form of social communication for the teens in this study. All told, 72% of all teens reported that they have used texting to contact friends and 54% of all teens text their friends on a daily basis. (Note, however that this still means that 28% of teens never text message with friends.) As discussed earlier in this chapter, the picture that emerges from the material is that, while teen boys have taken to text messaging, it is the teen girls – and older teen girls in particular – who are the most active texters. Comments from the focus groups indicate that texting is a quick and functional way to ask questions or to coordinate interaction. A high school-age girl who participated in the focus groups said:

- I mean, texting is really handy if you have to ask somebody a question, but you know that if you call them it is going to be at least an hour long conversation. And, I mean, usually, I feel like that is usually the case if I have to ask, ‘What time is this thing that we have to do this weekend?’ You know, those types of questions, where you just have to ask one quick question and that is all you really need from the person. You don’t have the time or you are not really in the mood to have a huge conversation.

While these data show that there are more instances of texting than phone calling, this should not be confused with the assertion that teens “do more” in texts than in phone calls. The information exchanged in one call can be the same as that contained in several texts and phone calls are richer social experiences because they convey more emotional information than texts. There is, however, a correlation between calling and texting activity. In general, those teens who call a lot also text a lot. The opposite, however, is not as true. Teens who text a lot do not always call as much.

Texting compared with talking: Why texting is preferred over talking

Texting compared with talking:

While texting is the major way teens communicate, it isn’t always the preferred method when talking with different people. When asked to choose, teens were clear about which modes of communication they preferred for talking with different people in their lives. For friends, who for most teens make up the bulk of their conversational partners, text messaging was dominant, with 67% of text-using teens saying they are more likely to use their cell phone to text a friend than to call. Still, a significant minority of text-using teens – 28% — said they preferred talking to their friends rather than texting them. Another 5% of texting teens said they were equally likely to call or text.

Conversely, 78% of text-using teens say they are more likely to use voice communication when they needed to talk to their parents. Just 18% of teens said that they were most likely to text their parents when reaching out and 4% were equally likely to call or text. As a high school boy in our focus groups noted, “I call my parents mostly, more so than text them, and then if, like, with my friends, if we need to get like set plans or something, we’ll kind of like call because it’s kind of like a lot less time than texting back and forth and waiting.”

Text-using teens are split on their preferred method for talking to siblings or other family members; 55% of these teens say they were most likely to talk by voice with brothers, sisters and other family, while 38% say they are most apt to text with other family members. Another 4% say they are likely to use both methods to reach out to family.

Parents and siblings aren’t uniform in their preferred modes of communication. Many teens in the focus groups spoke of texting one parent while calling another. “Well, my brother at college, we text a lot during the day and then my mom hates texting so I always call her,” explained a high school girl. “And then my dad thinks he’s cool when he texts so he always texts me.”

Texting edges out voice calling as the primary way these teens contacted significant others. A bit less than half of texting teens (42%) who have a boyfriend or girlfriend say they primarily text one another, and another quarter (26%) say they mostly talk with their significant other. Just 9% of teens say they use both, and an additional 7% said they use neither text nor talk to primarily communicate with a boyfriend or girlfriend. Overall, about 22% of teens say they do not have a significant other.

Girls are more likely to text friends and parents than boys.

When it comes to choosing a mode of communication to use when reaching out to friends, girls are more likely than boys to text their friends, with 74% of text-using girls saying they primarily text their friends, compared with 59% of text-using boys. Younger teens ages 12-13 were more apt than older teens to say they use both methods of communication rather than privileging either text or talk. Teens with dial up connections at home are also more likely to text their friends, with 81% saying they primarily text, compared with 65% of teens with a home broadband connection.

Girls who text are more likely to say they primarily text with their parents or guardian than boys, with 22% of girls texting parents compared with 13% of boys. Nearly 84% of boys mostly talk with parents, while three-quarters (73%) of girls say the same. Teens with parents who have less than a high school education or who are Hispanic are also less likely to say they text with parents than those with more education or white teens.

Texting or talking with siblings or significant others shows little variation by sex, age, race or socio-economic status. The one exception is that teens in lower income households are slightly less likely than teens from wealthier families to say they primarily text their significant other.

Why texting is preferred over talking:

There are several reasons that teens would choose texting over talking. Texting allows for asynchronous interaction and it is more discrete than making voice calls. Texting can be a buffer when dealing with parents and can be safer when interacting with potential romantic partners. Finally, it is a simple way to keep up with friends when there is nothing special that needs to be communicated.

Since texting is asynchronous, it does not necessarily command the attention of a conversational partner. This means that a teen can send a message and then simply await the answer. The person receiving it can deal with the message as their situation allows. It gives them the possibility to interlace the communication into other parts of their lives. A middle school boy describes this when he says:

- I usually text my parents, as well. Like, I guess although I’m not really supposed to in school I’ll just start texting them. I’ll just be like, ‘Hey mom come pick me up, this is happening,’ Or just, ‘Hey mom I forgot this can you drop it off?’ I don’t use the calling that much.

Texting is used in situations when it is discourteous, or even prohibited, to talk on the cell phone. For example, when teens are at the movies, in a public setting — or indeed during the focus groups held for this project — it can be socially awkward to conduct a voice call. In some cases texting can be a type of advanced note-passing to people who are close by or in the same room. The fact that texts mask the conversation means that they can serve as a “back channel” for interaction. When asked if she ever texted to people who were sitting nearby, a middle school girl said:

- I only do that when it’s like, you’re on a double date or something, and you’re like, ‘Oh how’s it going with your guy?’, And they’re like, ‘Oh I need to get out of here he’s so annoying.’ Like you’re hanging out in a huge group and you have a problem with one of the girls and you text your other friend. That’s the only time I do it. It’s usually girls that do it to each other. But guys know when you do it, they’re like, ‘You’re texting each other aren’t you?’

In other cases, texting is used to get around rules and for cheating.

-

Interviewer: . . . What about cheating? Have you heard of people using their phones for cheating?

High school boy: Yes.

Interviewer: How do they do that?

High school boy: They text like, ‘What is number 15?” “This is the question.”

High school girl: There is this thing Cha Cha and you can text it any question and it will give you an answer.46

Texting can be used to cover one’s tracks. Since obviously there is no sound when texting, teens can text their parents when the background noise of their location would give away too much information on their whereabouts. A high school boy described how his mother saw through this ruse:

- I would sometimes, I would text my mom, like, she, like, knows. She says to me, ‘Sometimes I know you’re doing something wrong if you’re texting me.’ She says she knows that, usually she’s right if I tell her I’m supposed to be somewhere else. If she calls she can hear the background, if she calls she says, ‘Who are you with? Who are you talking to? Where are you?’ If I’m texting it doesn’t give the location as much [because] she can’t hear the background.

Along the same lines, texting can be used as a buffer. Since there is not synchronous interaction and since it is somewhat more difficult to construct a text (often more so for parents than for teens), teens use text messaging when they have to break bad news or make an uncomfortable request of their parents. A high school girl described this when she said:

- I usually text my mom whenever I want to ask her something or tell her something bad. That way I don’t have to hear her yelling at me, like, give me a reason why I shouldn’t go, or why she doesn’t want me to go. ‘Cause she doesn’t text, she just, like, writes short answers. I usually text her everything else I want her to know so I don’t have to hear [her voice].

The fact that texting is slower than calling means there is not as much a need for spontaneity. When texting with potential boyfriends or girlfriends, the delay afforded by texting means that the teen has more control over the pace and tone of the interaction. A teen might edit comments and even consult with friends as to the best response. This issue can arise in mundane interactions like disagreements with friends, as well as in romantic situations.

Some teens simply prefer to text with friends, for the clarity that words on the screen can bring, and the removal of the awkward moments found in phone conversations. This is the way one high school boy explained it:

- Some people are bad at talking on the phone, like some people just really want silence and don’t really want to talk. Like when I text I can just say what I want to say and I don’t have to constantly be talking. If I have nothing else to say then I will just stop texting you. Or if we just run out of stuff, we just stop texting. Whereas on the phone you attempt to just keep on …I mean on the phone, you always try to make the conversation go longer—if you are talking to somebody, not if you are calling to ask for something. So, it depends on who I am talking to.

Some teens also report choosing texting over calling because it gives them more time to craft a message or respond in tough situations. As a high school girl noted:

- It just occurred to me, I don’t particularly use, but I know some people who do: If they know that they have to talk about something that might be a little tough. There is an argument with a parent or something like that. Texting can be easier because you can think about how you want to respond, you are not just like on the spot on the phone when somebody drops some like big news and like, ‘Ah, ah, I don’t know how to respond to this.’ Texting will give you some time.

Finally, texting is an easy way to keep up with the flow of everyday life. Several teens noted that to call means that it is something that is important. However, if the teens are simply checking in with one another, texting is an easy way to touch base. A middle school boy said, “If I’m texting, it’s just people I hang out with everyday.” And a high school girl said, “I text more than I talk. . . like my family I call, but its like friends and stuff text me.”

Mobile voice: Sometimes has advantages over texting.

As noted earlier in this chapter, after texting, the most common way to contact friends was calling via the cell phone. Overall, 72% of all teens, not just those with a cell phone, say they make voice calls on a mobile phone and 38% did so on a daily basis. Among cell phone owners, 50% made calls on a daily basis. Interestingly only 4% of those with a mobile phone reported never making calls. This compares with 28% who never use the texting function. Put another way, while 96% of teens who have a mobile phone use it to make calls, “only” 72% use it for texting. Clearly, some teens prefer talking to texting. In the words of one teen girl, “I mean, I dislike texting. I also don’t really like speaking on cell phones, but I definitely talk more than text.”

As with texting, it is the older teen girls who are the most active callers. Looking only at those who had a cell phone, 65% of the older teen girls (14 – 17) said that they used mobile voice. This compares with 47% of boys of the same age, 42% of 12 – 13 year-old girls and only 28% of 12 – 13 year-old boys.

Looking for a moment at teens who own a cell phone but do not use the voice function, the youngest teen boys are over represented. The data show that 10% of them report never making a voice call while only 2% of the 14 – 17 year-old girls report the same.

There is an economic consideration associated with the use of mobile voice. Sixty-three percent of those teens with unlimited voice subscriptions reported daily use where only 47% of those who had fixed minute subscriptions and 31% of those who had a set amount of money to use, as in pre-paid cell phone plans used voice minutes daily.

Why call and not text?

While texting is the most frequently used form of interaction, some teens prefer talking on their cell phones. There are a variety of reasons why teens might choose calling as opposed to texting. There is an immediacy and a fullness to voice interaction that is not often possible with texting, and talking provides teens with more social cues allowing them more nuanced interaction. In addition, texting can be too laborious and some people, usually parents, are out of the texting loop.

The teens in the focus groups said that they, or their parents, preferred voice when there was a need for immediate feedback. They preferred calling when they needed to talk about something that was important or serious. In these cases, the asynchronous nature of texting is not sufficient. Middle school boys noted:

- Boy 1: Most of the time you usually call your parents. You usually call them if it’s really important, or you’re trying to get a hold of them to come pick you up. So most of the time you usually call your parents but with friends you just text pretty much.

- Boy 2: My mom usually calls me if it’s, like, something serious, she calls me. If she’s like, mad, or serious about something, or, like, she needs to talk to me, she usually just calls me because it’s faster.

Another advantage of calling is that it provides more social cues. Texting provides a limited register with which teens can express their emotions (i.e. emoticons, the use of punctuation, capital letters, coarse language, etc.). In addition, text messages are not spontaneous. Rather, their construction can be calibrated and edited. By contrast, hearing another person’s voice provides a more direct gauge of their emotional state. One middle school boy described it this way:

- I only call if it’s really important because texting, the thing about texting is you can’t tell the emotion of the person really, as much as you can in their voice, so if it’s something really important I’ll call, but if I’m saying, ‘Hey you want to come over later,’ I’ll just text.

A middle school girl says much the same thing:

- I like to talk because I like to hear, because sometimes on AIM or texting I get mixed up from people’s emotions. They’ll be like, ‘Oh stop talking to me,’ and you don’t know if they’re joking or not joking. It’s kind of annoying.

Other teens prefer the verbal cues that come with voice calling. One high school girl explained:

- See, I would rather, if I’m like [annoyed] or something I would rather call my friends than text them about it. Because I’d rather hear them talking to me and being like, “It’s okay, everything is going to be fine,” than …like read that on a screen, it is less personal.

These comments suggest that texting is a form of communication that is used in a broad spectrum of mundane interactions. It is used when there is no need for immediacy or when one is concerned about how their conversation partner is going to interpret and respond to the communication. When there is a pressing need to contact another person, or when there is the danger that a text will be misunderstood, then calling is preferred.

Indeed, teens say that they used texting and voice interaction strategically. In those cases where they feel as though they needed to judge the reaction of their conversation partner, voice has an advantage. When using voice they can adjust or fine-tune the exchange as it develops. A middle school girl explained:

- If I’m looking for a clear response, I can see what they’re thinking or so I can [hear] their reaction then I’d probably call them. But. . .. I guess I would text sometimes if I have to tell someone that I’m not going to be able to make it or something like that, or decline an offer.

It is apparent that when this participant needed to shield herself from the reaction of someone whom she thought she had disappointed, the more indirect medium of texting was preferable. By contrast, calling allowed her to adjust her interaction based on the subtle voice cues.

In some cases, talking to a single individual is not enough. The teens in the focus groups described using the conference call functionality of the cell phone. Some high school girls described a familiarity and an expertise with this functionality that surpasses that of many other groups in society:

- Interviewer 1: Alex, you talked about three-way calling. So you set up a call between several people?

Girl 1: Ya. Like, um, um, you call one person and then you press talk or flash or whichever option you have on your phone and then it switches you to the other line and then you dial the number and three-way.

Interviewer 2: But then all three of you can talk together?

Girl 1: Yeah.

Interviewer 2: Can you do four, five, six?

Girl 1: Um Hmm.

Girl 2: If the person, that like, how you said she calls someone and then someone else calls someone…and you keep doing it…but it becomes really crowded after a while.

Girl 3: It’s hard to like hear yourself over everybody else talking.

Interviewer 1: How many of you have done that?

Girl 4: I do four-way all the time.

Interviewer 2: And you just, on your phone? On your mobile phone?

All: [agreement]

Interviewer 1: And how many is it usually like? Like three, or is it eight. . .

[Multiple Voices]: Two…three…we got five…like three… I do six.

Multi-person conversations are not confined to voice calling. The teens in the focus groups described having several texting threads open simultaneously, each thread a conversation with a different person. Yet in texting, multi-party conversations are most often a set of one-on-one exchanges, thus it is easier to conduct group conversation by voice. When calling, the teen can recognize the voice of a particular person. This facilitates the interaction, though, as the comments indicate, it can become awkward when too many people try to speak at once. Nonetheless, the teens, and in particular the teen girls, felt comfortable making multi-party calls so that they could chat with a collection of their friends.

According to the teens in the focus groups, another reason to prefer calling is simply that it is easier. The process of keying in the words, particularly if they are not familiar with word prediction functions such as T9, mean that composing a text message on the cell phone’s keypad can be a laborious process. Comments from middle school boys indicate that this may be more of an issue for them than for the teen girls:

- High School Boy 1: Guys usually call, but we’re lazy.

High School Boy 2: I text like 2%. Sometimes I try it out but after a while I’m like I don’t want to do this. So I’ll call.

Interviewer: Because you like calling better?

High School Boy 2: Because my phone has the regular numeric numbers. I don’t have the words or anything. So when I’m texting I have to press the letter twice or something if I want a certain letter.

Even teens who are more accustomed to texting often prefer voice when they are composing longer messages. The teens said that the efficiency of speaking trumps texting when they need to write longer texts or when they need to have many interactions in order to work out an agreement. One middle school boy said:

- I call people sometimes when the story is too long to text, so if someone says, ‘What happened?’ I won’t send them, like, a six page text message, I will just call them and tell them really fast.

Calling allows the teens to avoid writing long and complex text messages. If the text interaction is difficult and involves many turns or long, multifaceted passages, it is sometimes easier to call.

Parents can’t text: People who are outside the loop of texting

Another area where voice interaction edges out texting is in communication with parents. While it is true that some parents are proficient texters, many teens feel that their parents are not adept texters. While 71% of parents say they text, in the words of one teen, “My dad is clueless when it comes to texting — like, he has to stop to text.” Teens are far less likely to text with their parents than with their friends. Another high school boy said:

- I usually text. I barely use my phone to call. The only person I call is my dad, he’s the only one who doesn’t know how to text yet. So I just call him.

In addition to the challenge of writing the texts, teens say that their parents are not comfortable with the style of the writing. A middle school boy noted:

- I like mostly call my parents because like when I text them, I use abbreviations a lot so they are just like, ‘What does that mean?’ and stuff like that. I don’t have time to give them meanings of abbreviations and stuff so that’s why I usually call them.

Others said that the style of writing in texts is an issue with their parents. Their parents react to their more stylized writing and ask them to use more traditional formulations. A high school girl commented:

- My mom, she’s old school too, but she loves texting. But the only reason why I don’t text her is because I do the up-and-down letter-thingy, where you have capital, uppercase lowercase.

Interviewer: And she can’t read that?

And she is very old-fashioned. She’s like, ‘Don’t send me a text message like that,’ so I just call her.

In these cases, calling cuts through the problem. Teens were able to avoid a discussion of their spelling and grammar with their parents by using the voice function of the phone.

In some cases, the parents show proficiency with texting, and are in frequent contact with their children via this mode of communication. A high school girl noted:

- My inbox and my outbox together, ah, they probably get like full at like 150. So I’ll probably delete the whole thing, because I can delete everything together. I can probably do that like twice or three times a day, and it still has some left over from the night, so I just start going over it in the morning. So, I’ll probably text like 200 to 300 a day. It’s mostly my mom, because she likes to text me all day, even though she’s not supposed to.

In addition to the frequency of texting, some parents are also advanced in their use of texting lingo. One teen girl noted “Well, my mom, she knows all text languages. She confuses me, like I’ve never heard that before.” Other research has shown that while some parents are active texters, this is more the exception than the rule.47

In some cases, the people with whom the teens wish to communicate do not have a texting subscription. When another person does not have a texting subscription, it is expensive for them to receive and send messages. This means that about the only way to contact them is via voice. A high school girl:

- I’ve got a friend who doesn’t have texting so whenever I need to talk to her I need to call her because she’s on the sports team with me and goes to my church so and if I need to talk to her I have to call her, and I have a cousin who doesn’t have texting. So I have to call her to talk to her.

In other cases, older family members simply did not have cell phones.

Other communication methods: Social network sites, face-to-face meetings, landline calls, instant messaging, and email

Social network sites: Arenas of communication with friends.

[more]

- My whole team has a thing on Facebook where like if there is a practice cancelled or – I mean you’ll get texts if there is a practice cancelled, too—but, um it’s just like everyone’s on Facebook a lot more so its just easier to send out like a group message. It’s like, ’We have a car wash this weekend, just to let you guys know,’ that type of thing, instead of emailing.

As with texting, the broad tendency is that older teen girls are more active in this sphere while younger teen boys are more reserved in their use. Among users of social network sites, 43% of the older teen girls report that they use it on a daily basis to communicate with friends. By contrast, only 29% of the younger teen boys use social network sites to communicate with their friends daily.

Face-to-face meetings: The ultimate encounters.

All told, about one in three teens reports face-to-face interaction daily with friends outside of school. At the other end of the scale, only about 4% report none of this type of social interaction. On a weekly basis, 85% of the teens report that they have non-school face-to-face social interaction.

Teen boys as well as older teen girls (ages 14-17) are more likely to report daily face-to-face social interaction than are younger teen girls (ages 12 -13). Some 35% of the teen boys and 36% of the older teen girls report daily face-to-face interaction outside of school. By contrast, only 22% of the younger teen girls report the same. Interestingly, internet users are also more active than non-internet users in face-to-face interaction: 34% of those who use the internet report daily face-to-face interaction, while only 18% of those who do not use the internet reported the same.

Landline telephones: Fading as communications tools?

Teen voice calling is not simply confined to mobile phones – the majority of American families with teens still have a landline telephone in their home and teens take advantage of it. Nearly one-third (30%) of teens report daily use of the landline telephone to contact their friends. Sixteen percent say that they never use the landline telephone for social interaction.

Sometimes use of the landline is the most convenient, sometimes there is a cost consideration, and sometimes there is poor cell phone coverage. When a teen is at home, they often use the landline phone in order to save the cost of airtime on a cell phone. However, some teens report that their families are cancelling landline subscriptions.

- Interviewer: Does anyone have a phone at home, like a landline phone?

Boy 1: My parents just cancelled it a few months ago.

Interviewer: Your parents cancelled it. Anybody else not have a land line, just a cell phone?

Boy 2: I don’t have one.

Boy 3: I probably wouldn’t but it comes with the internet, so. But otherwise we would have cancelled it a long time ago, everybody who lives in the house has a cell phone.

Indeed, 26% of teens in this survey reached on a cell phone live in households that do not have a landline phone, and 29% of all families say they receive all or almost all of their calls on a cellular phone. Overall, 8% of American families with teens ages 12-17 in the household do not have a landline telephone at all. And as we see with other communication channels, those who use the cell phone are also intense users of the landline phone.

Younger teen boys (aged 12 and 13) use the landline telephone significantly less than other groups. Where 16% of younger boys say they use the landline phone on a daily basis, 29% of the older teen boys (aged 14 – 17) and 28% of the younger teen girls (aged 12 – 13) report the same. By contrast, older teen girls (14 – 17 year-olds) report a significantly higher level of use than all other groups — 39% of them use the landline phone daily to interact with their friends.

Instant Messaging (IM): A digital communications tool pushed aside by texting and absorbed by social network sites.

All told, 62% of all teens report using instant messaging (IM), while 38% either do not have access or choose not to use it. About one in four of all internet-using teens (26%) uses instant messaging on a daily basis to communicate with friends outside of school. Further, an additional 30% use it at least weekly, 10% use it less than weekly. Since 2006, instant messaging by teens has remained flat, with 30% of teens instant messaging daily in 2006 compared with 26% of teens who message daily in 2009.

Instant messaging is a form of communication that has, perhaps, been eclipsed by social network and texting. Indeed, many social network sites offer instant messaging functionality for users within the network. This is reflected in the comments of a high school girl who said, “The only time I ever, like, instant message, is when you are in Facebook, there’s a part of it …where you can.”

Instant messaging is one form of communication for which older teen girls are not the dominant users. Instead, older girls share the mantle with older boys. Among internet users, 29% of the older teen boys and girls (14-17 year-olds) and 25% of the younger teen boys (12 -13) use instant messaging on a daily basis. Further, the data reflect that only about half as many younger teen girls use instant messaging (12%).

It is perhaps not surprising that the more frequently a teen uses the internet, the more likely he is to use instant messaging. One third (32%) of teens who use the internet on a daily basis also make daily use of instant messaging.

Email: The least likely to be used by teens.

Email is the least used of the communication forms examined. When compared with use in 2006, daily email use has declined slightly from 15% of internet users to 11% of internet users in 2009. Fully 41% of all teens say that they never use email when communicating with their peers outside of school. While not used often for informal peer interactions, email is used in more formal situations such as in school and by parents and other adults. This does not mean that it is seen in a positive light.

- Interviewer: Do people still use email?

Group: Yes, yes all the time.

High School Boy 1: Yeah, the teachers do! The teachers are like ridiculous with that especially if they have your parents’ email.

There are no major age or gender based differences in email use.

Texting, calling and social support.

One of the aims of the survey was to understand how cell phone use relates to key features of one’s support network. Respondents were asked to report how many individuals they “feel very close to” and discuss personal matters with. They were also asked how many of these close personal ties they contact through the cell phone for social support. Half of teens report having 5 or more close personal ties, with the remaining teens reporting fewer ties. The cell phone plays an important role in social support from these relationships, with nearly half (48%) of teens reporting they use their phone to discuss personal matters with “all” of their close ties. The remainder say they use their phone for social support with “some” (25%) or “a few” (23%) of their close network ties. As noted elsewhere in this report, older teens are more likely to text their friends on a daily basis. In addition, they are more likely to use text messaging (and the cell phone more broadly) for social support. Girls are more likely than boys to text their friends on a daily basis and to use text messaging as a means for social support.

Heavy cell phone users have larger support networks.

To gain further insight into how these characteristics of one’s support system map onto cell phone use, correlations were run with daily levels of voice calling and text messaging. There is a positive relationship between voice calling and the size of one’s close personal network, and voice calling is also positively related to using the cell phone as a resource for reaching out to these individuals for social support. Heavy texters also tend to have significantly more close personal ties. However, unlike voice calling, text messaging is not significantly related to tapping into those relationships for social support through the cell phone. These findings offer evidence of how the cell phone helps to maintain larger networks of close personal ties, and, in the case of voice calling, it serves as a resource for social support when teens need to discuss personal matters.

Responses from the focus groups corroborate these findings in the sense that the cell phone was discussed primarily as a bonding resource for the teens. Text messaging was especially discussed as a way of staying in contact with their close personal ties. As one high school boy remarked, most of his texts are primarily with “close friends, and some family members that actually know how to text.” Others agreed, stating they primarily text with close friends, but also acknowledged that “at times” they would text with others they were not as close to, especially when they wanted to avoid the awkwardness of face-to-face or voice interaction with someone they did not like or know.

Part 4: Smart phones, new features, the internet and the digital divide.

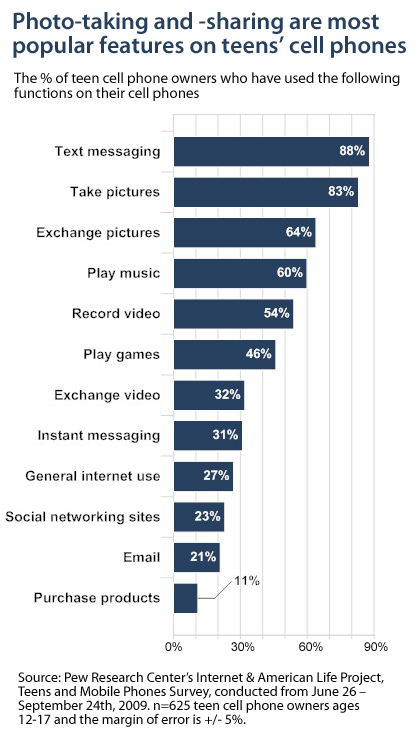

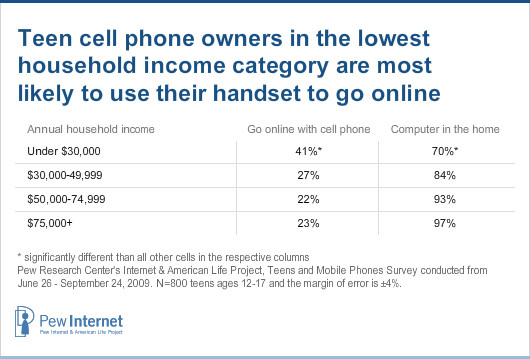

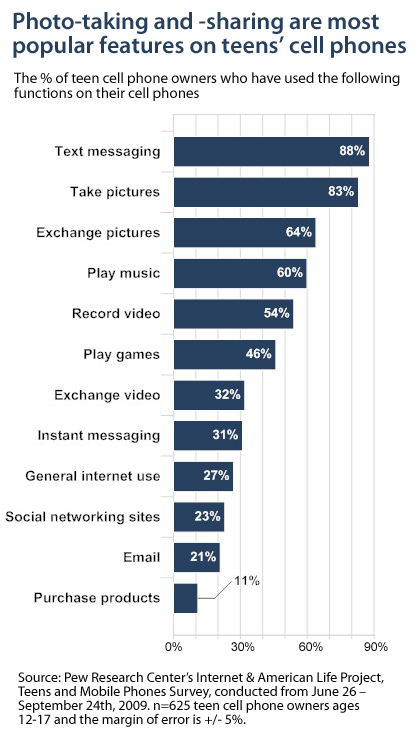

Beyond text messaging and voice calling, teens reported using several other features of their cell phones. The chart below provides a high-level snapshot of the percentage of teens who use their handset to go online, email, access social network sites, instant message, take/exchange pictures, take/exchange video, play music/games, and make purchases. The ensuing sub-sections provide more detailed analysis of the usage patterns associated with these technological affordances.

A sizable minority of teens use their cell phone to go online.

In examining how and how often teens use their cell phones to go online, the survey asked about general internet use, email, and social network sites. While these areas do not comprise an exhaustive list of activities, they reflect some of the key aspects of mobile internet use among teens in the U.S.

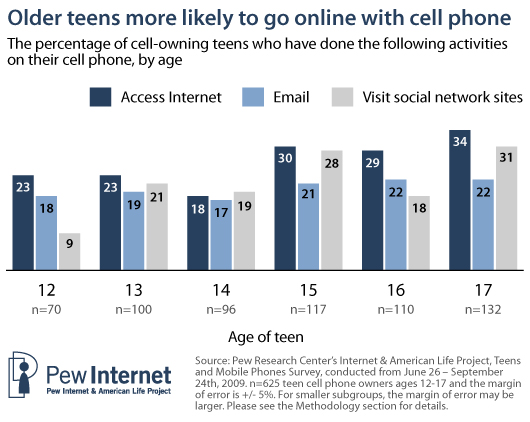

Cell phones help bridge the digital divide by providing internet access to less-privileged teens.

When asked whether they ever use the internet from their cell phones, 27% of cell phone users replied yes. Girls (30%) and boys (24%) both report going online with their handsets, though the difference is not statistically significant. With 73% of teen cell phone users not going online with their cell phones, it is clear that the computer is still their primary resource for using the internet. Looking at the breakdown according to age, the figure above shows that older teens with cell phones are more likely to go online with their cell phones than younger users. This difference may reflect a difference in disposable income to pay for Mobile internet connectivity, as many teens begin earning their own money through summer jobs and part-time employment during the school year as they grow older. Teens with their own separate service plan are more likely to use the cell phone to go online (39%) than those who are covered by a family plan (26%), further suggesting that as they grow more independent, teens use their resources to expand their use of the cell phone.

[The]

- I had the internet [on my phone] for a while but I didn’t really use it because I didn’t really need it. So my mom cut it and was like, ‘You aren’t using it.’ But now I realize I would like to have it, but my mom said it’s too much money so she won’t get it back on.

[using the cell phone to go online]

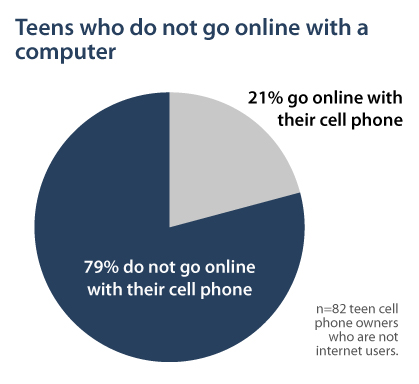

The cell phone provides an opportunity to access the internet for a sizable portion of cell phone users who do not go online otherwise.

One notable finding about internet access is that, among teen cell phone owners, 21% of those who do not go online or use email through a conventional computer instead use their phone handset to go online. In other words, the cell phone provides an opportunity to access the internet for a sizable portion of users who do not go online otherwise.

A more careful look at how household income relates to going online sheds more light on the situation. On the surface, one might find it surprising that teen cell phone owners in the lowest household income category are most likely to use their handset to go online. However, this might be explained by the fact that members of the lowest income category are also the least likely to have a computer in the home. That is, the cell phone appears to be a viable alternative for internet access for some teens living in households that cannot afford computers.

There are also racial and ethnic differences in cell phone-based internet use, with certain minorities being significantly more likely to use their cell phone to go online than white teens. More specifically, 44% of teens whose parents are black and 35% of those with Hispanic parents use their cell phone to go online, as opposed to 21% of teens with white parents.

These trends reveal an interesting paradox. On the one hand, going online through the cell phone is cost-prohibitive for many teens, especially younger ones who must rely on their parents to pay for this service. At the same time, it also provides teens from lower income households without a computer an opportunity to use the internet, hence helping to bridge the digital divide.

Specific activities done on the cell phone

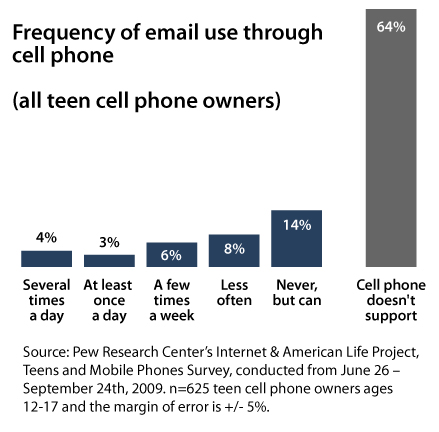

One in 5 teen cell phone owners email through their handset.

While 93% of teens say they use email, only 21% of those who own cell phones use the technology to send or receive email. Not surprisingly, there is a significant difference between computer-based internet users and non-users, with 21% of internet users emailing through their cell phones, as opposed to only 8% of non-users.

While just 21% of cell phone owners using email on their mobile devices may seem low, it is important to note that most teen cell phone owners (64%) say that their cell phone does not support email. This means that the majority of those whose cell phones do support email, use it at least occasionally. However, as shown in the table below, this is still not one of their heaviest uses of cell phone technology.

The relatively infrequent use of email through the cell phone can likely be explained by the fact that cell phones are primarily a social resource that teens use for connecting with their friends, and email is not one of the primary means through which they maintain their peer relationships. To illustrate, only 11% reported that they use email (through any device) with their friends on a daily basis, as opposed to 54% of total teens, including non-cell phone owners, who text message their friends every day.

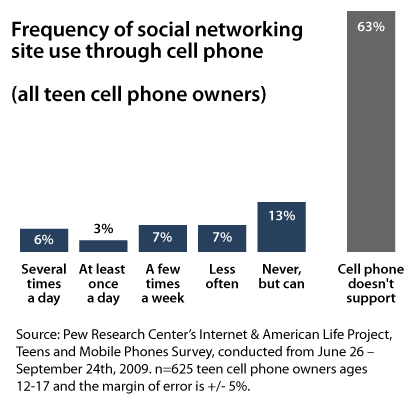

Use of social network sites through the cell phone:

Overall, teens have come to embrace social network sites, particularly Facebook and MySpace. In recent years, the percentage of teens who use social network sites has steadily risen to 73%. Trends for using social network sites through the cell phone are similar to those for email, with 23% of teen cell phone owners reporting that they have used the technology to access social networks (21% of boys, 23% of girls). Most of the teens whose handsets and/or service plans support this functionality use it, although 13% of those who can still do not. As shown in the table below, use of social network sites through the cell phone tends not to be a daily activity for those who do this.

Broadly speaking, accessing social network sites is not a primary use of the cell phone, however some respondents in the focus groups indicated social networks are a primary reason for going online with their cell phones. For example, when asked about internet use with the cell phone, one boy in middle school replied, “I get on MySpace a lot but that’s it.” A high school girl in another session explained that she used to go online for other purposes with her cell phone, “but now it’s just Facebook.”

The focus group sessions indicated that Facebook and MySpace are the most frequently used social network sites through the cell phone, with a handful of teens also using it for Twitter. In some cases, the teens preferred using their cell phones over the computer for accessing social network sites, illustrated by the following remark from a boy in middle school: “I usually use Twitter and Facebook a lot on my phone. I use them on my phone more than the computer.” More often, however, teens express a preference for using the computer instead of the cell phone for this purpose. As is the case with general internet access, reasons include increased cost and diminished utility of the cell phone for online activity. As one high school girl stated, “Using Facebook through the phone is too expensive.” Another high school girl explained:

- My email comes to me, like email from Facebook. Like ‘you have a message from Facebook.’ I’d rather not check it on my phone. It just wastes like a lot of time, personally, I’d just rather … I just go whenever I can get on a computer.

This comment was echoed by a middle school boy who said he goes on MySpace through his phone to “look up stuff,” but not pictures and video because “it’s different from the internet,” meaning it is a different and often lesser experience than using a computer to go online.

Instant Messaging on the cell phone:

Like email and social network sites, instant messaging is also another potential phone-based online activity for teens. Among those who own a cell phone, 31% use their handset to send and receive instant messages (29% of boys, 33% of girls). Instant messaging through the cell phone is most popular among 17 year-olds, with 45% doing this at least occasionally. In contrast, younger teens tend to instant message through their cell phones less often, particularly 13 and 14 year-olds (19% and 21%, respectively, report doing so at least occasionally). This age trend is attributable to differences between older and younger girls. That is, only 17% of female cell phone owners ages 12-13 use instant messaging through their handset, as opposed to 38% of girls 14 or older. This disparity is noteworthy, considering there is no difference between boys in these age groups – 29% of boys in each age group send instant messages through their cell phone.

Responses from the focus groups indicate that AOL’s instant messaging service (AIM) is popular among teens. AIM is used on computers as well as cell phones, and allows individuals to communicate across these two platforms. As one middle school boy explained, “They have AOL, like AIM, it’s supported by my phone. So if one of my friends don’t have a phone, they can get on the computer and text me on my phone.”

Photos and video through the cell phone – entertaining oneself and sharing with others.

The survey and focus groups revealed that taking and exchanging photos and video are popular uses of the cell phone among teens in the U.S. In fact, the number of teen cell phone owners who have taken a picture with their handset (83%) rivals the number who use the text messaging feature (87%). The frequency with which they take pictures is notably lower, however, with just 10% of those who have camera phones report that they take photos “several times a day,” as opposed to 63% who text message this often.

[the money]

Videos are also popular, although they are taken and exchanged less often than pictures through the cell phone. This is likely due to technological limitations. As one middle school boy explained, “I take videos but they can only be like two minutes or something.” As with pictures, videos are often taken when teens encounter something funny and want to share it with their friends. However, the focus groups also indicated that for some teens, taking video was something they tended to do more in a family context. Teens in our focus groups remarked:

- Last year my brother graduated from 12th grade. I went with my sister. We went to my brother’s graduation, and I had it recorded because my mother wasn’t able to go. So I took it and sent it to her. (Girl, high school)

- I recorded a video. My brother used to have really long hair, like longer than me, so I recorded him cutting his hair and put it on YouTube. (Girl, high school)

- I take videos of my sister. (Boy, middle school)

Older teens are more likely to snap and share photos with their cell phones, while younger teens are more likely to exchange videos with their cell phones.

Teen cell phone owners in the 14-17 age group are slightly more likely to take photos than those ages 12-13 (85% vs. 77%). This older category of teens is also somewhat more likely to send/receive photos than the younger group of teens (67% vs. 56%). However, there is an interesting counter-trend, with more 12-13 year-olds sending/receiving video than those 14 and older (41% vs. 27%). The chart linked to below illustrates age trends for the use of cell phone photos and videos.

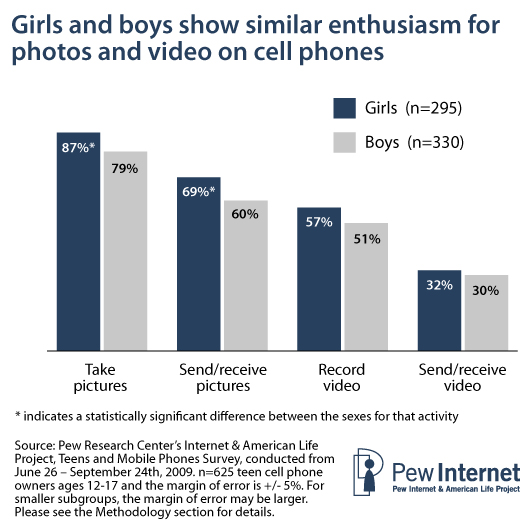

With regard to sex, the next chart shows that girls tend to be heavier users of these photo features than boys. Among teen cell phone owners, 79% of boys take photos at least occasionally, as opposed to 87% of girls. Fifty-nine percent of boys send or receive photos, whereas 69% of girls do this.

Teens also use the cell phone to play games, play music, and, to a lesser extent, make purchases.

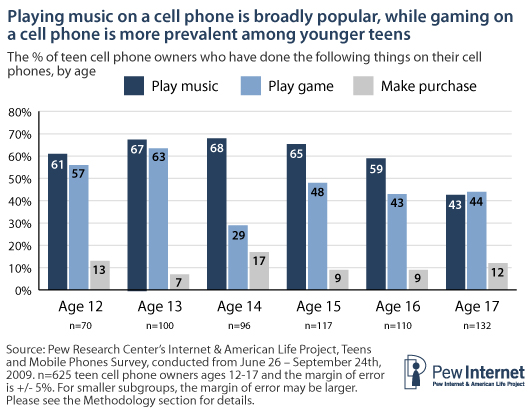

Video games and digital music are key sources of entertainment for teens. Overall, 80% report owning a game console, and 79% have an iPod or other digital music player. When looking at cell phone trends for playing music and games, we see another area where the technology is highly regarded and used as a source of entertainment among teens. Sixty percent of teen cell phone owners report using their phones to play music at least occasionally. Generally, it is the younger users who are more likely to do this. For example, well over 60% of teens between 12 and 15 play music on the cell phone, as opposed to 43% of 17 year-olds. With the exception of 12 year-olds, this trend for younger teens does not appear to be related to owning an iPod or MP3 player. While 32% of 12 year-olds do not own an iPod or MP3 player, and therefore might rely on their cell phone for music, ownership of iPods and MP3 players dramatically rises after the age of 12, with well over 80% of teens age 13-16 owning one. However, playing music on the cell phone is still popular for these individuals. Generally, there is not much difference between boys with cell phones (58%) and girls with phones (62%) when it comes to playing music on the cell phone at least occasionally. However, when looking at the statement for playing music at least once a day we see 45% of girls 12-13 saying they do that compared with only 28% of boys in this age group.

Playing games through their cell phone tends to be more of an occasional rather than an everyday activity for teen cell phone owners, but still quite popular considering 46% report doing so at least sometimes. Age trends for playing games replicate earlier findings about video games at large,48 and are fairly similar to those for playing music, with younger teen cell phone owners (61% of 12-13 year-olds) being more likely to do this than older teens (42% of 14-17 year-olds). Equal portions of boys and girls play games on a handset.