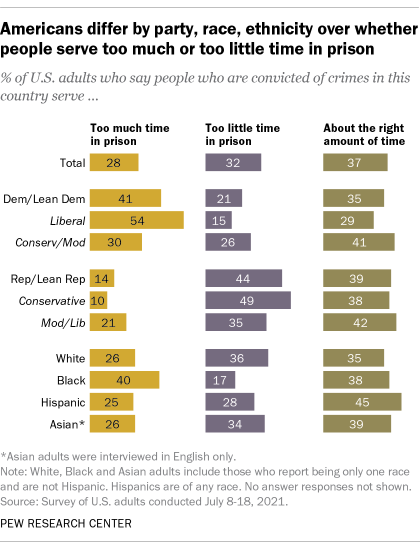

Americans are closely divided over whether people convicted of crimes spend too much, too little or about the right amount of time in prison, with especially notable differences in views by party affiliation, ideology, race and ethnicity.

Overall, 28% of U.S. adults say people convicted of crimes spend too much time in prison, while 32% say they spend too little time and 37% say they spend about the right amount of time, according to a Pew Research Center survey of 10,221 adults conducted in July 2021. The question was asked as part of a broader survey examining differences in Americans’ political attitudes and values across a range of topics. The survey asked about prison time in a general way and did not address penalties for specific crime types.

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are much more likely to say people convicted of crimes spend too much time in prison than to say they spend too little time behind bars (41% vs. 21%). The reverse is true among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents: 44% of Republicans say people convicted of crimes spend too little time in prison, while 14% say they spend too much time behind bars. Around a third of Democrats and Democratic leaners (35%) and a slightly higher share of Republicans and GOP leaners (39%) say people convicted of crimes spend about the right amount of time in prison.

This analysis examines Americans’ attitudes about the amount of time served in prison by people who are convicted of crimes in the United States. It includes a separate analysis of average time served among people released from state prison in 2018.

The public opinion data in this analysis is based on a Pew Research Center survey of 10,221 adults conducted July 8-18, 2021. Everyone who took part in the survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology. Here is the question used for this analysis, along with responses, and the survey’s methodology.

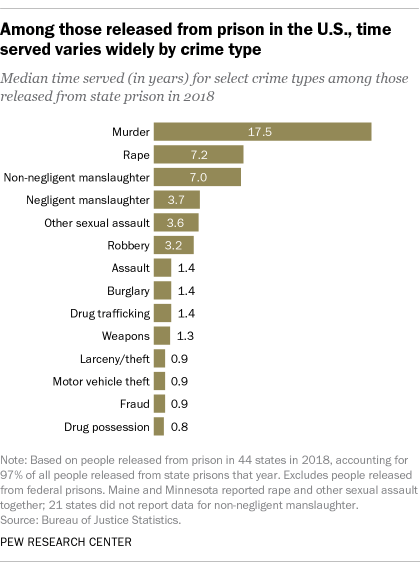

Data on the average amount of time that people convicted of crimes serve in prison comes from a 2021 Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) study. The study examined time served among people released from prison in 44 states in 2018, accounting for 97% of all people released from state prisons that year. The study did not include Alaska, Idaho, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Oregon, Vermont or the District of Columbia. It also excluded people released from federal prisons. The study looked only at people released from prison in 2018. It did not examine time served by those who remained in prison or were ineligible for release, or those sentenced to a year or less. Time-served data for Maine and Minnesota combines rape and other sexual assault, while 21 states did not report time served for non-negligent manslaughter.

This analysis describes average time served using medians, not means. Mean time served can be considerably longer than median time served due a relatively small number of released prisoners who served unusually long periods of time behind bars.

Views differ by ideology within each partisan group. Liberal Democrats are more likely than conservative and moderate Democrats (54% vs. 30%) to say convicted people spend too much time in prison. Conservative Republicans are more likely than moderate and liberal Republicans (49% vs. 35%) to say people convicted of crimes spend too little time in prison.

Democrats who describe their political views as very liberal and Republicans who describe their views as very conservative stand out even more. Very liberal Democrats are much more likely than Democrats who describe their views as simply liberal (70% vs. 47%) to say convicted people spend too much time in prison. And very conservative Republicans are more likely than Republicans who describe their views as simply conservative (56% vs. 47%) to say people convicted of crimes spend too little time in prison.

Attitudes about many aspects of the U.S. criminal justice system differ by race and ethnicity, as previous Pew Research Center surveys have shown, and a similar pattern appears in views of time spent in prison. Black adults (40%) are more likely than White (26%), Asian (26%) and Hispanic adults (25%) to say people convicted of crimes spend too much time in prison. Conversely, White adults (36%) are more likely than Hispanic (28%) and Black adults (17%) to believe that convicted people spend too little time behind bars. Around a third of Asian adults (34%) also say convicted people do not spend enough time in prison, but their views are not statistically different from those of White and Hispanic adults.

Among Democrats, similar shares of Black and White adults say prisoners spend too much time behind bars, even as Black and White Democrats express different views on some other survey questions related to criminal justice. Black Democrats, for example, are modestly more likely than White Democrats to favor increased funding for police in their area, according to a September Pew Research Center survey.

The U.S. imprisonment rate has steadily declined since the mid-2000s, with an especially sharp decline among Black Americans. Still, the imprisonment rate of Black Americans remains more than five times as high as that of White Americans. The number of Black prisoners also exceeds the number of White prisoners, even though Black people account for a much smaller proportion of the nation’s adult population.

Time served in prison varies widely by crime type

So how much time do people convicted of crimes in the United States actually spend in prison?

Not surprisingly, the answer varies substantially by crime type, according to a study released earlier this year by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), which examined the records of people released from prison in 44 states in 2018, accounting for 97% of all people released from state prisons that year. (The study looked only at people released from prison. It did not examine time served by those who remained in prison or were ineligible for release. The study also excluded people released from federal prisons. For more details about the study’s methodology, read the “How we did this” box above.)

Across all crime types, people released from state prison in 2018 spent a median of 1.3 years in prison, with longer periods of imprisonment for those convicted of violent offenses and shorter periods for those convicted of other offenses, such as property and drug crimes.

In the violent crime category, people convicted of murder spent a median of 17.5 years in prison before being released, while the median amount of time served was lower for those convicted of rape (7.2 years), non-negligent manslaughter (7.0 years), negligent manslaughter (3.7 years), other sexual assault (3.6 years), robbery (3.2 years) and assault (1.4 years).

In the property crime category, the median time served was 17 months for those convicted of burglary and 11 months for larceny/theft, motor vehicle theft and fraud. Among drug crimes, those convicted of trafficking offenses served a median of 17 months, compared with 9 months for those convicted of possession. People convicted of weapons offenses – which are classified as “public order” crimes in the BJS study – served a median of 15 months before being released from prison in 2018.

When considering these figures, it’s important to note that time served is not the same measure as sentence imposed. People who are convicted of crimes tend to serve less time than what they receive at sentencing, often due to credits for good behavior or participation in programs while in prison.