Americans have mixed views of the job performance of those who hold positions of power and responsibility in eight major U.S. groups and institutions. A key element in shaping these views is their sense of whether members of these groups act ethically and hold themselves accountable for their mistakes, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

The groups studied included members of Congress, local elected officials, leaders of technology companies, journalists, religious leaders, police officers, principals at public K-12 schools and military leaders.

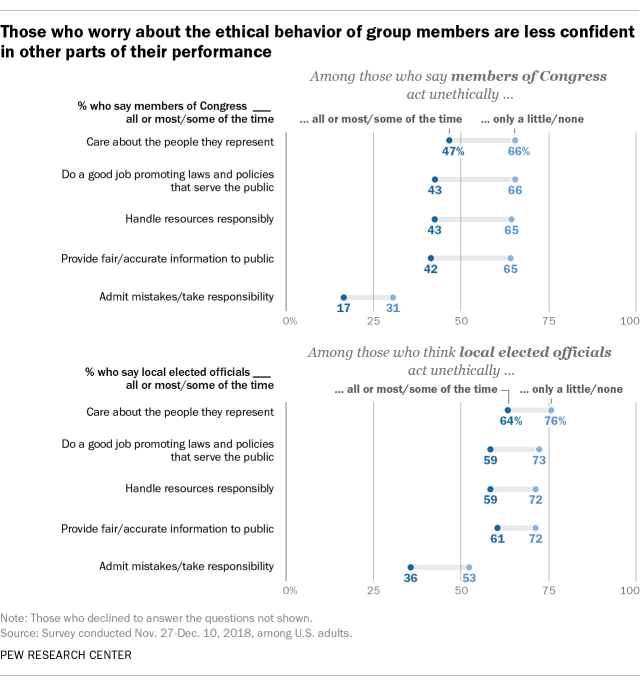

The survey found that the more confident people are that group members behave unethically, the less likely they are to have confidence in other aspects of that group’s performance. Conversely, U.S. adults who think group members admit mistakes and take responsibility for them have relatively high levels of confidence in key performance activities of that group.

For example, those who think that members of Congress act unethically “all or most of the time” or “some of the time” are less likely to say the lawmakers care about “the people they represent” than are those who think members of Congress rarely act unethically (47% vs. 66%).

Similar differences show up when the public judges if members of Congress do a good job promoting laws and policies that serve the public, handle resources responsibly and provide fair and accurate information. Two-thirds (66%) of those who think lawmakers mostly act ethically say they are doing a good job serving the public, but 43% of those who see members of Congress as mostly unethical say members of Congress do a good job serving the public.

Just 17% of those who have relatively negative opinions about the ethical behavior of members of Congress think the lawmakers admit mistakes and take responsibility for them, compared with 31% of those who think members of Congress behave ethically at least some of the time. A similar pattern holds when the performance of local elected officials is considered.

There are also wide gaps in judging the performance of journalists. Those who think journalists behave relatively unethically are less likely to say journalists care about people like them than those who think journalists are relatively ethical (45% vs. 69%). The same divides show up when asked if journalists do a good job reporting important news that serves the public (61% vs. 81%), cover all sides of an issue fairly (47% vs. 71%) and admit mistakes and take responsibility for them (37% vs. 62%).

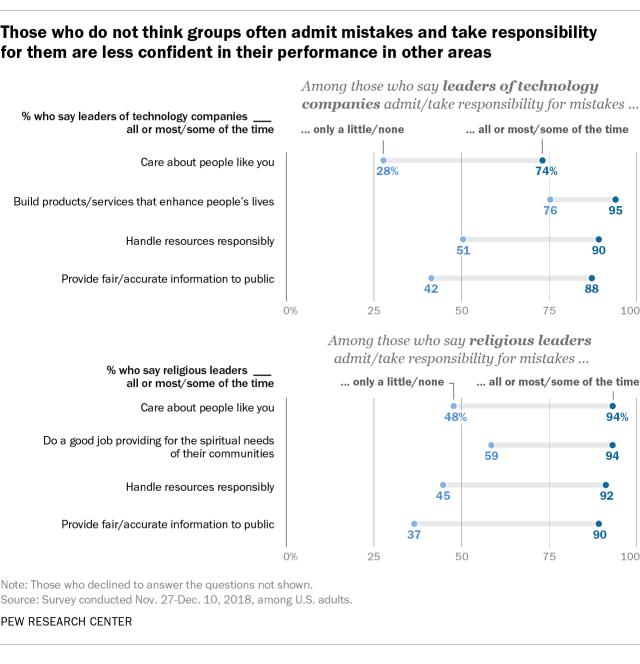

A comparable dynamic plays out when the issue relates to whether those who hold these positions of power and responsibility admit and take responsibility for mistakes. Those who think group members are relatively transparent about mistakes are more likely to think positively about other aspects of a group’s performance than those who think the group members do not regularly admit mistakes and take responsibility for them.

Those who think leaders of technology companies don’t sufficiently admit and take responsibility for mistakes are less likely to judge other performance aspects of their work positively than those who think the leaders do take responsibility for mistakes “all or most of the time” or “some of the time.”

The same dynamic also applies when the performance issue is whether tech leaders “care about people like you” (28% vs. 74%), handle resources responsibly (51% vs. 90%) or provide fair and accurate information to the public (42% vs. 88%).

The gaps between those who have relatively positive views about religious leaders and those who have relatively negative views are particularly striking. There is a 53 percentage point gap between those who think religious leaders take responsibility for their mistakes and those who do not when the issue is whether religious leaders provide fair and accurate information to the public. And there is a 47-point gap when the issue is whether religious leaders handle resources responsibly, a 46-point gap when the issue is whether religious leaders care about “people like you” and a 35-point gap when the issue is whether religious leaders do a good job providing for the spiritual needs of their communities.

Note: See full topline results and methodology.