As the Federal Communications Commission continues to address broadband infrastructure and access, Americans have mixed views on two policies designed to encourage broadband adoption, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

A substantial majority of the public (70%) believes local governments should be able to build their own broadband networks if existing services in the area are either too expensive or not good enough, according to the survey, conducted March 13-27. Just 27% of U.S. adults say these so-called municipal broadband networks should not be allowed. (A number of state laws currently prevent cities from building their own high-speed networks, and several U.S. senators recently introduced a bill that would ban these restrictions.)

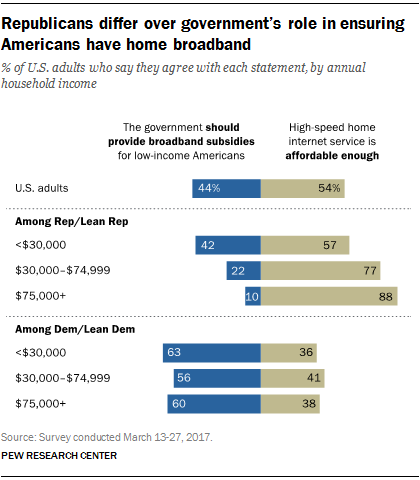

At the same time, fewer than half of Americans (44%) think the government should provide subsidies to help lower-income Americans pay for high-speed internet at home. A larger share (54%) says high-speed home internet service is affordable enough that nearly every household should be able to buy service on its own.

Broadband has been a high-profile issue in the early days of the Trump administration. In February, the new FCC chairman, Ajit Pai, scaled back a broadband subsidy program for lower-income Americans. And last week, President Donald Trump signed legislation that repeals a number of broadband privacy regulations.

Americans have different levels of support for broadband subsidies based on political affiliation. Six-in-ten Democrats and independents who lean Democratic say the government should help lower-income Americans purchase high-speed internet service, but that figure falls to just 24% among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents. These partisan differences stand in stark contrast to attitudes toward municipal broadband networks, which are favored by a solid majority of both Democrats (74%) and Republicans (67%).

A majority of Democrats at various income levels support government subsidies for broadband, but there are significant differences among Republicans based on income. For example, 42% of Republicans and Republican leaners with an annual household income of less than $30,000 support broadband subsidies for lower-income Americans. But that figure falls to just 10% among Republicans from households earning $75,000 or more a year. Overall, however, Republicans at all income levels are less likely to support broadband subsidies than Democrats of comparable incomes.

Beyond partisan affiliation, support for broadband subsidies varies by a number of other factors, including race and ethnicity. About six-in-ten blacks (59%) and Hispanics (57%) say the government should help lower-income Americans obtain broadband service, compared with just 37% of whites. Similarly, 55% of those with an annual household income of less than $30,000 support these subsidies, but that share falls to 35% among households earning $75,000 or more.

Meanwhile, there are only modest differences on this question between those who currently subscribe to broadband at home and those who do not: 42% of Americans who use broadband at home support government subsidies for lower-income adults to purchase broadband service, compared with 52% of those who do not currently subscribe to home high-speed service.

By contrast, a majority of Americans across a wide range of demographic groups are in favor of local governments being able to build their own high-speed networks.

Around half of Americans view home broadband as essential

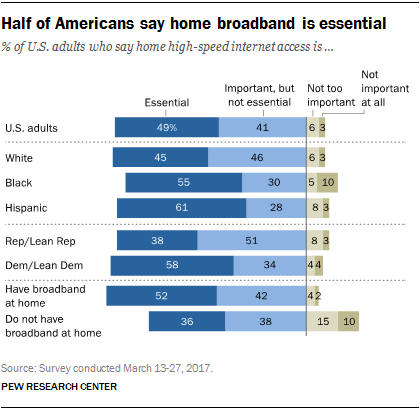

These policy debates are occurring at a time when roughly nine-in-ten Americans describe high-speed internet service as either essential (49%) or important but not essential (41%). Only about one-in-ten Americans say that high-speed internet access is either not too important (6%) or not important at all (3%).

Republicans and Democrats tend to agree that broadband is important, but Democrats are more likely to say it is essential: 58% of Democrats and Democratic leaners describe broadband in this way, compared with 38% of Republicans and Republican leaners. A similar split is evident by race and ethnicity, with blacks (55%) and Hispanics (61%) more likely than whites (45%) to say that high-speed access at home is essential.

Current broadband users also place a higher value on high-speed access: 52% of current users describe the service as essential, compared with 36% among non-users. In fact, roughly a quarter of those who do not have broadband in their homes say that high-speed internet service is either not too important (15%) or not important at all (10%). Previous Pew Research Center surveys have found that broadband users see greater value in high-speed access at home than non-users, although there is evidence that attitudes among non-users have been growing more positive in recent years.

Americans’ broadband knowledge is relatively mixed

In general, Americans have a relatively accurate understanding of what share of the population actually subscribes to broadband service. The survey asked respondents to estimate what percentage of Americans have high-speed internet access in their homes, and the median (typical) response was 70% – just 3 percentage points off the 73% of Americans who reported having broadband access in the most recent Pew Research Center survey of broadband adoption. Even so, around a quarter of Americans believe less than half the population has broadband, while 7% think that more than nine-in-ten Americans are broadband adopters.

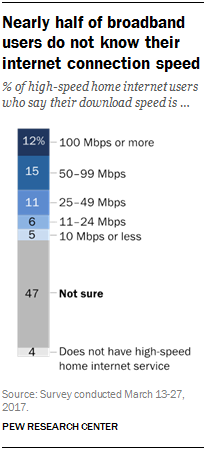

On the other hand, fewer current broadband users know what their own internet access speed is. When asked what download speed they have for their own home internet service, 47% were not able to provide an answer. The remaining users offered a range of estimates, from 10 megabits per second or less (which is how 5% of current subscribers describe their connection speed) to 100 Mbps or more (12%).

Note: Full methodology, topline and detailed tables are available here.