Multiracial identity is not just the sum of the races on someone’s family tree. It’s more complicated than that.

Multiracial identity is not just the sum of the races on someone’s family tree. It’s more complicated than that.

How you were raised, how you see yourself and how the world sees you have a profound effect in shaping multiracial identity, the survey finds. For many mixed-race Americans, these powerful influences may be as important as racial background in shaping their racial identity.

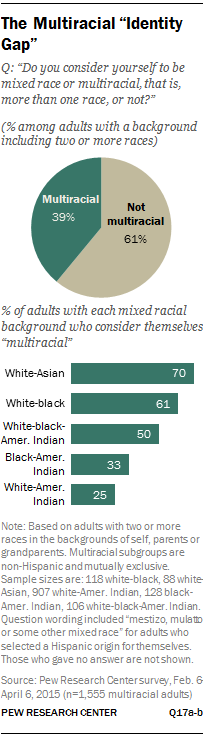

In fact, when asked, “Do you consider yourself to be mixed race or multiracial, that is, more than one race, or not?,” a substantial majority of Americans with a background that includes more than one race (61%) say that they do not consider themselves to be multiracial.45

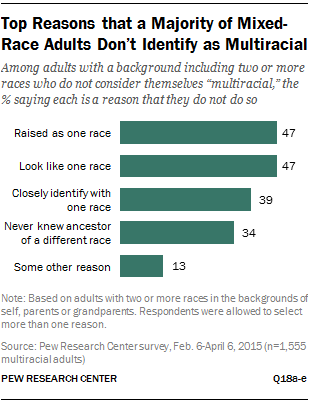

When asked why they don’t identify as multiracial, about half (47%) say it is because they look like one race. An identical proportion say they were raised as one race, while about four-in-ten (39%) say they closely identify with a single race. And about a third (34%) say they never knew the family member or ancestor who was a different race. (Individuals were allowed to select multiple reasons.)

This multiracial “identity gap” plays out in distinctly different ways in different mixed-race groups.

A quarter of biracial adults with a white and American Indian background say they consider themselves multiracial, for example.

By contrast, seven-in-ten white and Asian biracial adults and 61% of those with a white and black background say they identify as multiracial. Multiracial adults with a white, black and American Indian racial background (50%) or a black and American Indian biracial background (33%) fall between these groups in terms of the share who say they identify as multiracial. Among Hispanics who count two or more races in their background, about six-in-ten (62%) say they consider themselves to be multiracial.

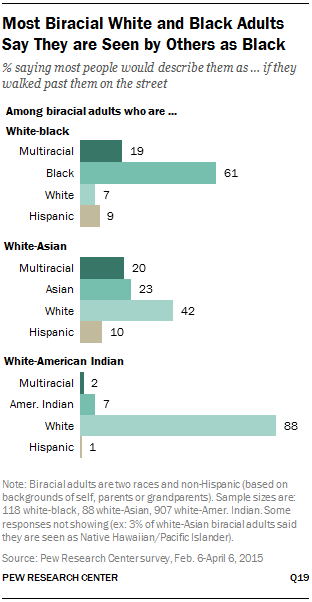

The survey also finds that the way in which people describe their own racial background doesn’t always match the way they believe others see them. About nine-in-ten white and American Indian biracial adults (88%) believe that a stranger passing them on the street would say they were single-race white; only 2% say they would be seen as multiracial and 7% as American Indian only.

By contrast, six-in-ten Americans with a white and black background (61%) believe they are seen as black; only 19% say they would be seen as multiracial (an additional 7% say they would be perceived as white only). Among white and Asian biracial adults, 42% say others would perceive them as white and 23% think others see them as Asian. Two-in-ten say they would be seen as multiracial.

Measuring multiracial identity is complicated for other reasons. Many mixed-race Americans say that over the course of their lifetimes they have changed how they viewed their racial identity. According to the survey, about three-in-ten mixed-race adults (29%) who now report more than one race for themselves say they used to see themselves as just one race. But among those who did not report more than one race for themselves in this survey—but instead are included in the multiracial group because of the races they reported for their parents or grandparents—an identical share have switched their racial identity: 29% say they once saw themselves as more than one race but now see themselves as one race.

The survey also shows multiracial adults sometimes feel pressure to identify as a single race. About one-in-five mixed-race adults (21%) say they have been pressured by friends, family members or “society in general” to identify as a single race.

The remainder of this chapter examines in more detail the multiracial identity gap and how physical appearance, personal values, societal pressures and other factors help shape an individual’s racial identity.

Sometimes I identify as white because it’s easy. … Sometimes I just get tired of explaining who I am, and sometimes I just don’t care to. I also recognize that since I look white I sometimes identify that way because I know that’s what they think.White and American Indian biracial woman, age 27

A Mixed Racial Background, but Not Multiracial

Only about four-in-ten adults (39%) with a background including more than one race consider themselves to be multiracial, while the majority of these adults (61%) do not.

Only about four-in-ten adults (39%) with a background including more than one race consider themselves to be multiracial, while the majority of these adults (61%) do not.

Among adults with multiple races in their background who do not consider themselves to be multiracial, about half say their physical appearance (47%) and/or family upbringing (47%)—nature and nurture—are among the reasons that they do not identify as multiracial. Some 39% say they closely identify with one race, and about a third (34%) say they never knew their family member or ancestor who was a different race.

An additional 13% give some other reason for not identifying as multiracial, including 4% who say their racial background is unimportant to them, 2% who say the family member of a different race is too many generations removed and 2% who simply don’t identify with their multiracial heritage.

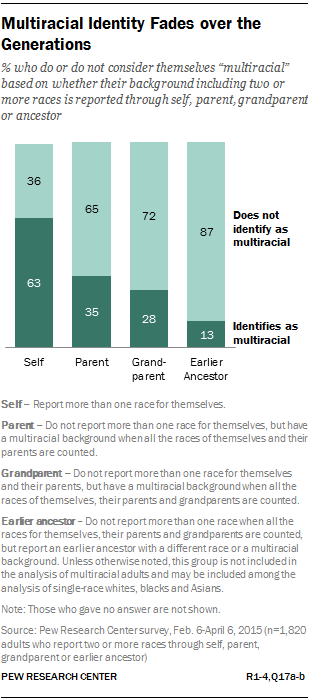

Fading Multicultural Identity

The survey finds that multiracial identity quickly fades with the generations. Among those whose ties to a mixed racial background come from a great-grandparent or earlier ancestor—a group that is not included among the analysis of multiracial Americans throughout this report—only 13% consider themselves to be multiracial. The share roughly doubles (to 28%) if a grandparent had a racial background that was different from that of the respondent and his or her parents, and it rises to 35% if one or both parents had a different racial background than the respondent.

I identify with the African-American culture more. One because I just look it. When an average person is walking down the street, they just see a guy who is colored. A man of color. Brown.Black and Asian biracial man, age 47

Among those who report that they themselves are two or more races, about six-in-ten (63%) identify as multiracial. But even for this group, roughly a third (36%) do not consider themselves mixed race.

Among those who report that they themselves are two or more races, about six-in-ten (63%) identify as multiracial. But even for this group, roughly a third (36%) do not consider themselves mixed race.

And it is among this group, the 36% who self-report that they are two or more races but don’t consider themselves multiracial, that the power of physical appearance to shape racial identity comes into focus. Among these mixed-race Americans, the proportion who say they do not identify as multiracial because they “look like one race” increases from 47% (among all multiple-race adults who do not consider themselves multiracial) to 64%. About half (54%) of this group says the reason is that they were raised as only one race, while somewhat fewer (45%) say they closely identify as only one race. A third (33%) say they don’t identify as mixed race because they never knew their ancestor of a different race.

How Biracial Adults Think Others See Them

How do multiracial adults believe strangers passing them on the street see their racial background? The answer to that question varies substantially by mixed-race group. But one common thread runs through these responses: Few say they are viewed as multiracial.

According to the survey, only 9% of all multiracial adults believe they are perceived as a mix of races by others.

Among biracial adults who are white and black, 61% say they are perceived by strangers to be black. Only 19% say they are seen as multiracial, and even smaller shares say they are seen as single-race whites (7%). About one-in-ten (9%) of non-Hispanic white and black biracial adults say others would think they are Hispanic, and 3% say others would think they are American Indian.

Among biracial adults who are white and black, 61% say they are perceived by strangers to be black. Only 19% say they are seen as multiracial, and even smaller shares say they are seen as single-race whites (7%). About one-in-ten (9%) of non-Hispanic white and black biracial adults say others would think they are Hispanic, and 3% say others would think they are American Indian.

A virtually identical pattern appears among black and American Indian biracial adults. Among this group, roughly eight-in-ten (84%) say strangers would identify them as single-race black (6% say they would be seen as multiracial). And about six-in-ten white, black and American Indian multiracial adults (62%) also say others perceive them to be black (with 20% saying they would be seen as multiracial).

A significantly different pattern emerges among white and Asian biracial adults. Only about a quarter of this group (23%) says they are viewed as Asian, while 42% believe they are perceived as white. One-in-five white and Asian biracial adults say they are seen as having a multiracial background.

The overwhelming majority of white and American Indian biracial adults (88%) say they are seen as white. Only 2% say they are thought to be multiracial, and 7% believe they are seen as Native American. Even among those who consider themselves to be multiracial, eight-in-ten say they are perceived as white by others.

Among Hispanics who are more than one race, about a quarter (24%) say that a stranger would see them as Latino while 17% believe they would be viewed as multiracial.

It’s often funny and interesting to see people’s reactions when I do tell them that I’m actually half Japanese. ‘Oh, really?. … I guess I can see it. Your cheekbones or maybe a little bit in your eyes.’ But most people, say 8 out of 10, don’t see it at all.White and Asian biracial woman, age 43

Attempts to Influence How Others See Their Appearance

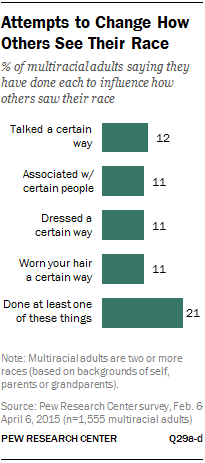

At some point in their lives, about one-in-five multiracial adults (21%) have dressed or behaved in a certain way in order to influence how others saw their race.

At some point in their lives, about one-in-five multiracial adults (21%) have dressed or behaved in a certain way in order to influence how others saw their race.

According to the survey, about one-in-ten multiracial adults have talked (12%), dressed (11%) or worn their hair (11%) in a certain way in order to affect how others saw their race.

A similar share (11%) say they associated with certain people to alter how others saw their racial identity. (The survey did not ask respondents to identify which race or races they sought to resemble.)

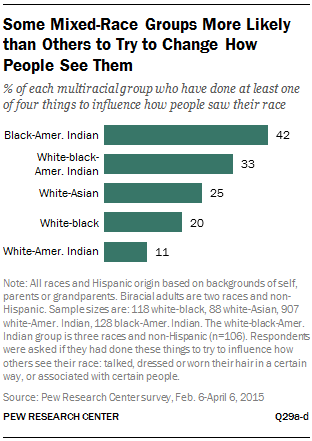

Efforts to affect perceptions by looking or behaving in a certain way varied widely across the largest multiracial groups.

About four-in-ten (42%) black and American Indian biracial adults say they have presented themselves in a certain way in order to affect how others saw their race. A third of all adults with a white, black and American Indian background and about the same share (34%) of multiracial Hispanics also say they have made an effort to change the way people see their race.

A quarter of white and Asian biracial adults and one-in-five white and black biracial respondents say that, at some point, they have tried to look or behave a certain way to influence how people thought about their race. Among the largest biracial subgroup—white and American Indian adults—only about one-in-ten (11%) say they have done this.

A quarter of white and Asian biracial adults and one-in-five white and black biracial respondents say that, at some point, they have tried to look or behave a certain way to influence how people thought about their race. Among the largest biracial subgroup—white and American Indian adults—only about one-in-ten (11%) say they have done this.

The survey also found that few multiracial adults have attempted to recast their racial identity to gain advantage when applying for college or scholarships.

Overall, only 5% of all mixed-race adults who have at least some college education say they have described their racial background differently than they usually would to get into college or qualify for a scholarship, including 13% of multiracial adults with an Asian background, 6% of black multiracial adults and 5% of mixed-race whites. (The survey did not ask how they described their identity differently.)

Growing up I remember wanting to get a relaxer for my hair. Even as a guy, I wanted my hair when it got wet to sort of fall down or have spikes. I wanted to dress a certain way because I wanted to embrace what I thought was … a white identity.White and black biracial man, age 25

Pressure to Identify as One Race

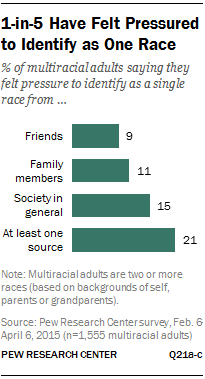

About one-in-five multiracial adults (21%) say they have felt pressure from friends, family or from society in general to choose one of the races in their background over another.

About one-in-five multiracial adults (21%) say they have felt pressure from friends, family or from society in general to choose one of the races in their background over another.

Multiracial adults feel the heat to identify as just one race more from “society in general” (15%) than from family members (11%) or friends (9%). (The survey did not ask respondents with which race they felt pressured to identify.)

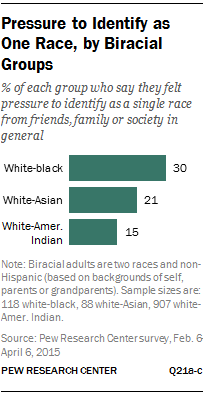

Multiracial adults with a black background are among the most likely to say they have felt pressure to identify as single race from at least one of the three sources tested in the survey. About three-in-ten biracial adults who are white and black (30%) or black and American Indian (28%) fall into this category.

Multiracial adults with a black background are among the most likely to say they have felt pressure to identify as single race from at least one of the three sources tested in the survey. About three-in-ten biracial adults who are white and black (30%) or black and American Indian (28%) fall into this category.

Roughly three-in-ten multiracial Hispanics (31%) and about two-in-ten adults with a white, black and American Indian racial background (23%) or a biracial white and Asian background (21%) also felt pressured. Some 15% of white and American Indian biracial adults felt pressed to say they are one race. The pressure to identify with a single race is particularly felt by those who believe they physically look like a mix of races and not like just one race. According to the survey, about a third (34%) of all mixed-race adults who say a passerby would identify them as multiracial also say they have felt pressure to identify as one race. By contrast, some 20% of those who believe that a stranger would identify them as single race or as Hispanic only say they have felt similar pressure.

Changes in Identity over the Life Course

An individual’s racial background is fixed at birth but his or her racial identity can change over the course of a lifetime, the Pew Research survey found.

About three-in-ten adults (29%) who now think of themselves as more than one race say they once thought of themselves as only one race. An identical share moved the opposite way: 29% of those who have a mixed racial background but see themselves as only one race say they used to think of themselves as more than one race.

There was a time when I didn’t identify as black. In fact, growing up I really hung onto this idea that I was biracial. … It wasn’t ’til college that I made that switch from identifying as biracial to being black.White and black biracial man, age 25

Multiracial Background and Personal Identity

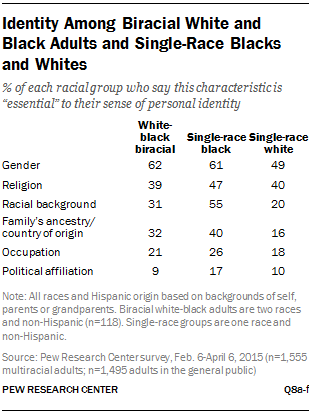

Multiracial adults and the general public generally define who they are around the same set of core characteristics and values, and they give the same relative importance to their racial background. About half of all Americans (51%) say their gender is “essential” to their personal identity, and virtually the same proportion of multiracial adults agrees (50%). Identical proportions (39%) of mixed-race Americans and the country as a whole say their religion is an essential part of who they are. About a quarter of both groups also say their racial background and their family ancestry are extremely important elements of their personal identity, while about one-in-five of both groups rate their occupation as essential to their personal identity.

Multiracial adults and the general public generally define who they are around the same set of core characteristics and values, and they give the same relative importance to their racial background. About half of all Americans (51%) say their gender is “essential” to their personal identity, and virtually the same proportion of multiracial adults agrees (50%). Identical proportions (39%) of mixed-race Americans and the country as a whole say their religion is an essential part of who they are. About a quarter of both groups also say their racial background and their family ancestry are extremely important elements of their personal identity, while about one-in-five of both groups rate their occupation as essential to their personal identity.

Multiracial adults and other Americans even agree on the least important of the six characteristics tested in the survey. Only about one-in-ten multiracial adults (10%) and adults in the general public (11%) consider political affiliation to be a core part of their identity.

With a few notable exceptions, similar proportions among the five largest multiracial groups and mixed-race Hispanics say these traits and characteristics are essential to their sense of self.

With a few notable exceptions, similar proportions among the five largest multiracial groups and mixed-race Hispanics say these traits and characteristics are essential to their sense of self.

Large differences emerged on the relative value that black, white and Asian mixed-race groups placed on their race as well as their family origin in determining their personal identity.

Overall, multiracial blacks are generally more likely than other mixed-race groups to see their racial background and family ancestry or country of origin as important parts of their personal identity.

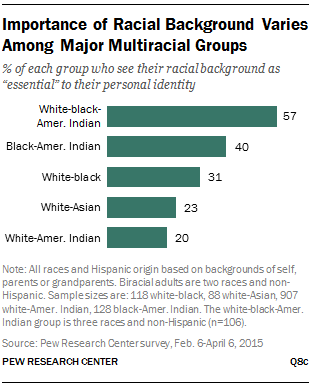

For example, fully 57% of white, black and American Indian multiracial adults say their racial background is essential to their sense of personal identity, roughly three times the share of white and Native American biracial adults (20%) who express this view.

Four-in-ten black and American Indian biracial adults say race is an extremely important part of who they are, as do 31% of white and black biracial adults.

Among biracial white and Asian adults, 23% say their racial background is essential to their personal identity. Only 15% of all multiracial Hispanics consider their racial mix to be central to who they are.

Significantly, the share of biracial adults with a white and black background (31%) who view their race as essential to their identity is substantially smaller than the proportion of single-race blacks (55%) who hold the same view. Single-race white adults are somewhat less likely than biracial white and black adults to consider their racial background to be an essential part of their overall identity; only 20% say it is.

Significantly, the share of biracial adults with a white and black background (31%) who view their race as essential to their identity is substantially smaller than the proportion of single-race blacks (55%) who hold the same view. Single-race white adults are somewhat less likely than biracial white and black adults to consider their racial background to be an essential part of their overall identity; only 20% say it is.

Multiracial blacks are more likely than other multiracial groups to consider their family ancestry or country of origin as key to their identity. For example, about a third (32%) of white and black biracial adults say their family ancestry is essential to their sense of who they are, double the proportion of white and American Indian biracial adults who hold that view. About four-in-ten black and American Indian adults (36%) and multiracial white, black and American Indian adults (42%) say their family’s ancestry or country of origin is essential to their identity. Among white and Asian biracial adults, 21% say this, as do 12% of multiracial Hispanics.

Most of the world sees me as white, but on a personal, more emotional level, I connect very strongly to [the Catawba tribal] community that I grew up with because it’s my family.White and American Indian biracial man, age 23