As any parent knows, combining work and family life can be complicated. The survey asked working parents how balancing work and family had affected their careers. Roughly a quarter (27%) said being a working mother or father had made it harder for them to advance in their job or career, and women were much more likely than men to express this view. An even higher share (38%) said being a working parent had made it harder for them to be a good parent. Again, women were more likely than men to fall into this category.

The survey finds that women experience family-related career interruptions at a much higher rate than men do. Among working mothers with children under age 18 who have ever worked, about half say they have taken a significant amount of time off from work (53%), and 51% say they have reduced their work hours to care for a child or other family member. The vast majority of these mothers say they are glad they took these steps, though many say it hurt their career overall.

Working Parents Face Challenges on the Job and at Home

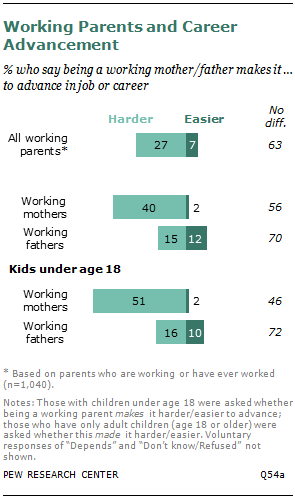

Among all adults who are either working and have children under age 18 or who worked when their children were growing up, a majority (63%) say being a working parent didn’t make a difference in their career advancement. For the remaining share of adults who say being a working parent did affect their ability to advance at work, most say the impact was negative. Some 27% say being a working parent made it harder for them to advance, while only 7% say this made things easier.

There is a significant gender gap on this question. Fully four-in-ten mothers who are currently working and raising their children or who worked when their children were young say that being a working mother has made it harder for them to advance in their job. Only 15% of working fathers say the same.

Among mothers whose children are currently under age 18, 51% say being a working mother makes it harder for them to advance in their career. This compares with only 16% of men with children under age 18. Women whose children are grown are somewhat less likely than women with younger children to say that being a working mother made it harder for them to get ahead at work. Roughly one-third of these women say being a working parent made it harder for them to advance at work. Still, this is about twice the share of men with grown children who say the same (13%).

Younger working mothers are among the most likely to say that being a working parent makes it harder for them to get ahead in their career. Among Millennial mothers who have worked, 58% say being a working mother makes it harder for them to get ahead at work. Of Millennial fathers who are working, only 19% say being a working father makes it harder for them to advance at work.

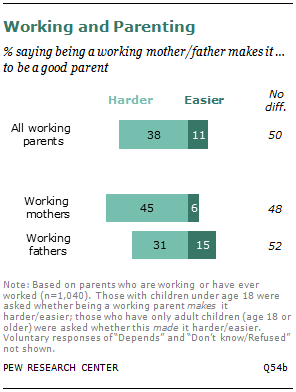

Balancing work and family life can also make parenting more challenging. Fully 38% of mothers and fathers say being a working parent makes it harder to be a good parent. About one-in-ten say being a working parent makes it easier to be a good parent, and 50% say it doesn’t make any difference.

Mothers are more likely than fathers to say that juggling work and family makes it harder to be a good parent (45% vs. 31%). And mothers who are still in the midst of childrearing have a more negative assessment than those whose children are already grown. Among working mothers with children under age 18, 55% say being a working mother makes it harder for them to be a good parent. By comparison, 39% of women whose children are age 18 or older say being a working mother made it harder for them to be a good parent.

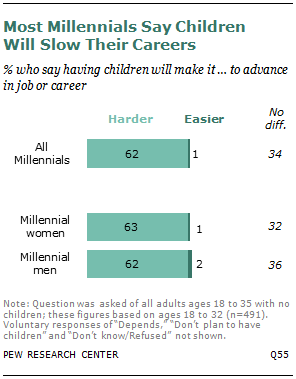

For young adults without children, there’s a strong expectation that having children will hinder their career advancement. Fully 62% of Millennials say that having children will make it harder for them to advance in their job or career. Roughly one-third (34%) expect that having children won’t make a difference in their career advancement, and only 1% say having children is likely to help them advance.

There is no gender gap on this question among young adults. Equal shares of Millennial women (63%) and Millennial men (62%) anticipate that having children will make it harder for them to advance in their career.

Career Interruptions

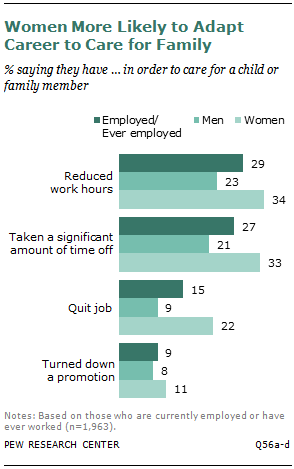

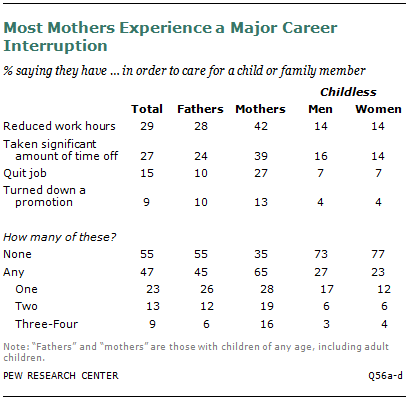

In order to balance work and family, many people have to make accommodations to their work schedules or even to their career ambitions. The survey finds that a significant share of adults have changed the course of their work life in order to care for a child or other family member, and women are much more likely than men to have done this.

Overall, 29% of adults who have ever worked say they have reduced their work hours in order to care for a child or other family member. Women are significantly more likely than men to have done this: 34% of women and 23% of men say they have cut back on their hours at work to care for their family.

Some 27% of adults with some experience in the labor force say they took a significant amount of time off from work at some point to care for a child or other family member. There is a similar gender gap on this issue: 33% of women, compared with 21% of men, say they took time out of their work life to care for a family member.

Overall, 15% of working adults say they quit a job in order to care for a family member. Again, women are more likely than men to have done this: 22% of women and 9% of men report having quit a job for family reasons at some point during their working life.

About one-in-ten adults with work experience (9%) say they turned down a promotion in order to care for a child or other family member. Roughly equal shares of women (11%) and men (8%) say they have done this.

Underlying the gender gap in career interruptions is a sharper gap between mothers and fathers. Mothers are much more likely than fathers to say they have reduced their work hours, taken a significant amount of time off from work or quit a job in order to care for a family member. Fully 42% of mothers say they reduced their work hours, compared with 28% of fathers. And a similar share of mothers (39%) say they took time off to care for a family member, compared with 24% of fathers.

Mothers are more than twice as likely as fathers to say they quit a job at some point in their working life, in order to care for a child or other family member. Mothers and fathers are about equally likely to say they have turned down a promotion for family reasons. Overall, 65% of mothers and 45% of fathers say they have done at least one of these things in order to meet the needs of their family.

To be sure, family care giving isn’t limited to parents. Roughly one-in-four childless adults say they have taken one of these steps in order to care for a family member. There is no significant gender gap among adults without children. Some 27% of men and 23% of women in this category say they have reduced their hours, taken time off, quit their job or turned down a promotion in order to care for their family.

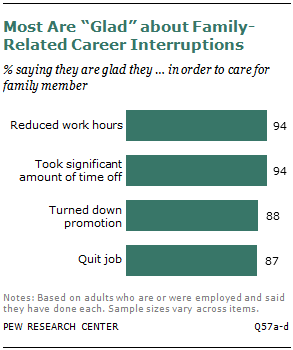

No Regrets about Career Interruptions

When respondents are asked if they are glad they took these steps in order to accommodate their family, the answer is a resounding yes. Among adults who have reduced their work hours in order to care for a child or other family member, 94% say they are glad they did it. An identical share of those who say they took off a significant amount of time to care for a family member says they are glad they did it.

Even among those adults who say they have turned down a promotion or quit a job in order to care for a family member, very few express regret. Fully 88% of those who have turned down a promotion and 87% of those who have quit a job say they are glad they did it. Men and women who have had these types of career interruptions are equally likely to say they don’t regret doing these things.

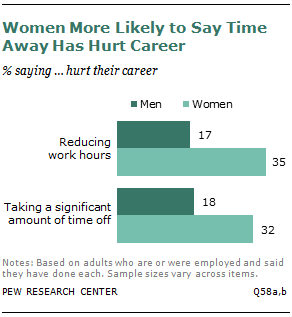

Women See Bigger Impact from Career Interruptions

Respondents who have experienced significant career interruptions were also asked what impact, if any, it had on their career. Among those who say they reduced their work hours or took a significant amount of time off from work in order to care for a family member, about two-thirds say doing this didn’t have much of an impact on their career. For those who did feel an impact, most say doing this hurt their career. Some 28% of those who reduced their work hours to care for a family member say this hurt their career overall, while only 4% say this helped their career. Similarly, 27% of those who took time off from work say that hurt their career; 6% say it helped.

There is a significant gender gap on the question of impact, with women much more likely than men to say taking these steps in order to care for their family hurt their career. Among women who say that they reduced their work hours in order to care for a child or family member, 35% say it hurt their career overall. By comparison, 17% of men who did the same say this hurt their career.

Roughly one-third of women who say they took a significant amount of time off from work to care for a family member say doing this hurt their career. Among men who took time off, only 18% say it hurt their career.

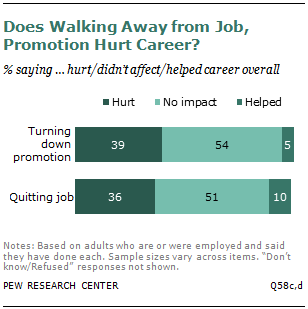

Among those adults who say they have quit a job or turned down a promotion in order to care for a family member, about half say it didn’t have an impact on their career. For the remainder, the impact was more likely to be negative than positive. Some 36% of those who have quit a job to care for a family member say doing this hurt their career; 10% say it helped. Similarly 39% of those who say they have turned down a promotion say this hurt their career, while only 5% say it helped.35