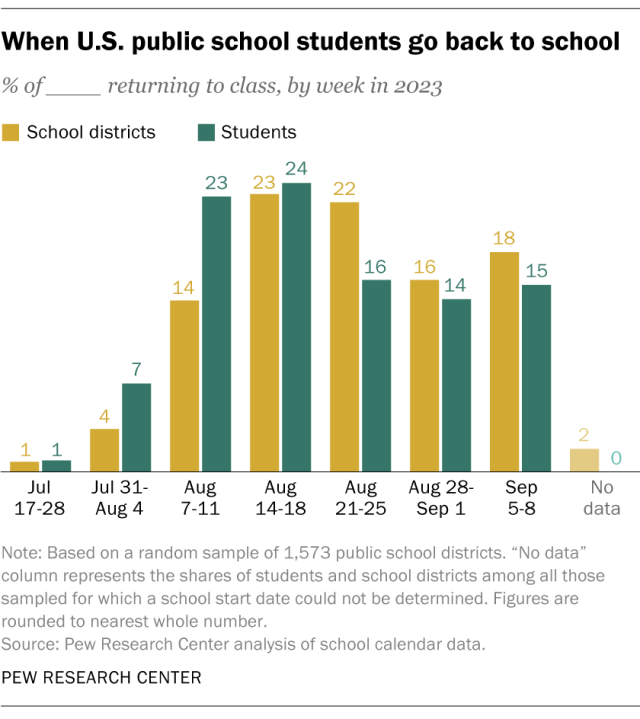

About 70% of the 46.7 million public school students in the United States are now back in class, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis. Depending on where you grew up or live now, your reaction might be, “That sounds about right,” “Already?” or “What took them so long?”

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to determine when public schools in the United States start classes. We collected school start dates for the 2023-24 school year from a nationally representative, stratified random sample of 1,573 districts.

To create this dataset, we began with a stratified random sample of 1,500 public school districts that was used in a 2023 Center analysis of school district mission statements (this analysis only covers “regular” public school districts and their equivalents; institutions such as charter schools and specialized state-run schools are excluded). That sample had been drawn from a comprehensive list of public school districts maintained by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). For more details for how that earlier sample was selected, read the methodology for that analysis.

We then supplemented that stratified sample in several ways:

- One district no longer exists and was removed from the dataset.

- Because school districts in Vermont, New Hampshire and New York City are classified not as “regular local districts” but as “component districts,” the initial sample missed them. So we drew an additional sample of 72 districts from those areas and added it to the original sample.

- The lone districts in Hawaii and Washington, D.C., neither of which were initially selected, were also added so that at least one district from all 50 states and the District of Columbia would be represented.

The data was weighted to account for each district’s probability of selection in both the initial and supplementary samples. Then it was calibrated so that both the weighted number of districts and the weighted number of students matched the totals for all eligible districts in the NCES list.

After these adjustments, we had a sample of 1,573 districts. For each one, we manually searched its website to find its 2023-24 calendar. If we couldn’t find a calendar (or a functioning website), we called the district office. In the end, we found start dates for 1,551 districts; the rest were coded as “no data.”

In most cases, districts had a single reopening date for all of their schools. When start dates varied, we used the date that applied to the most grade levels. In the few cases where we couldn’t determine that reliably, we went with the earliest reopening date on the calendar.

In some districts, certain schools may follow a “year-round” calendar rather than the “traditional” calendar (late summer/early fall to late spring/early summer). In those cases, we used the start date on the traditional calendars, since those were more comparable to the vast majority of U.S. school districts. As of the 2017-18 school year, only about 3% of public schools were on any type of year-round schedules, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s National Teacher and Principal Survey.

Student enrollment figures are taken from the NCES database and are for the 2021-22 school year. In addition, each district was coded as belonging to one of the U.S. Census Bureau’s nine geographic divisions for regional analysis.

Some, but not all, U.S. school districts offer prekindergarten classes. Student weights for each district in the sample include pre-K students when appropriate, but start dates are based on grades K-12.

Information on the laws and policies governing school start dates in each state came from the Education Commission of the States, a nonprofit research organization that serves education policymakers throughout the country.

For most U.S. K-12 students, the school year runs about 180 days, spread over roughly 10 months with a long summer vacation. Within that broad timeframe, however, there are substantial regional variations, according to our analysis of over 1,500 public school districts. (The analysis only covers “regular” public school districts and their equivalents; institutions such as charter schools and specialized state-run schools are excluded.)

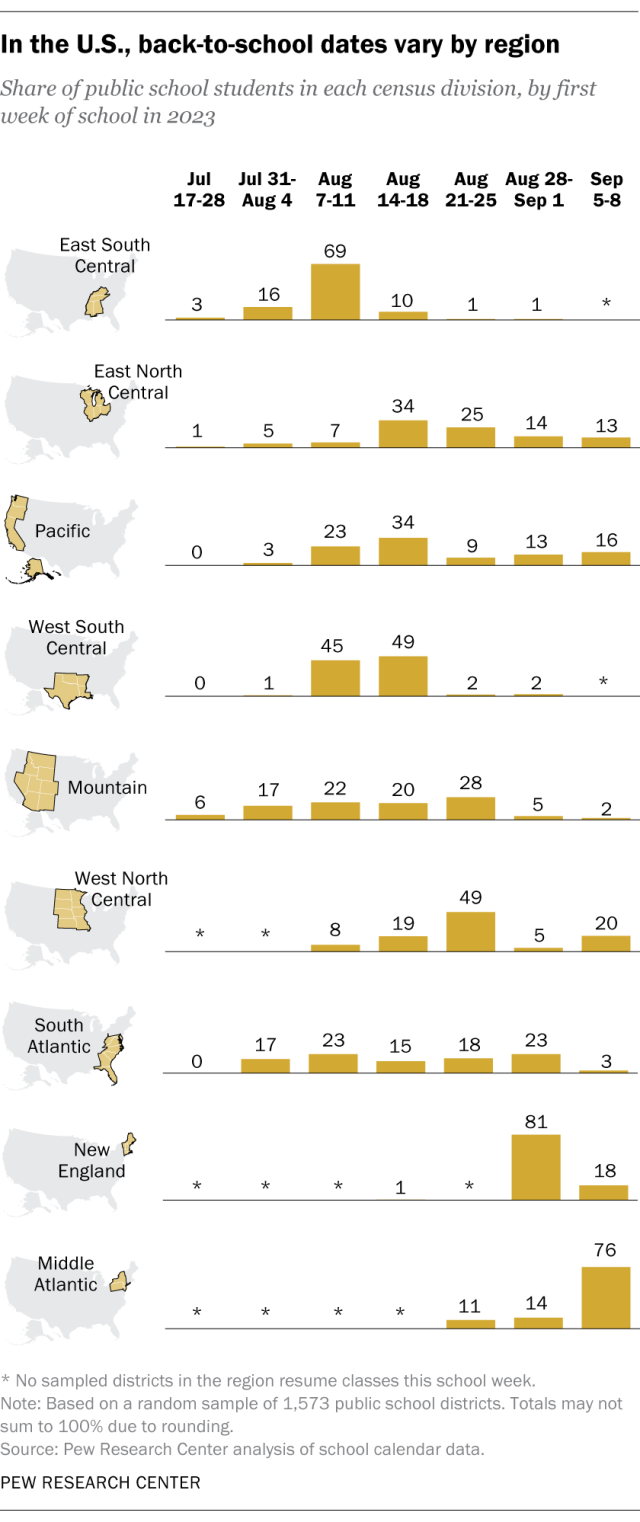

For example, school tends to start earlier in southern regions than farther north, broadly speaking. More than two-thirds of students in the U.S. Census Bureau’s East South Central division – Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee – went back to school the week of Aug. 7. They joined another 19% of students who had started classes earlier. In the West South Central division (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas), 94% of students returned to school between Aug. 7 and Aug. 18.

But in the six New England states, almost no one goes back to school before the week of Aug. 28. And students in the Middle Atlantic states – New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania – go back even later: About three-quarters won’t hit the books until after Labor Day, which falls on Sept. 4 this year.

Even within regions, districts in the southernmost states sometimes start classes earlier than those farther north. For instance, within the sprawling South Atlantic division, sampled districts in its southernmost states (Florida and Georgia) have similar start-date patterns to those in the East South Central region, while the division’s northernmost jurisdictions (Maryland, Delaware and D.C.) more closely resemble districts in regions up north.

Some states stand apart from the overall trends in their region in other ways. In the West North Central region, for instance, roughly two-thirds of public school students start classes between Aug. 14 and Aug. 25. However, Minnesota law requires schools to start after Labor Day in most cases, and the vast majority of sampled Minnesota districts will go back after the holiday.

In the Census Bureau’s eight-state Mountain division, which stretches from the Canadian border to the Mexican border, nearly half of public school students overall return to school between Aug. 14 and Aug. 25. But almost all of the sampled districts in Arizona and New Mexico, the two southernmost states in that division, start one to three weeks earlier.

Why do start dates vary so much?

While such geographic variations are fairly apparent, the reasons for them are less clear. State laws certainly play a part: 16 states establish windows, either by statute or rule, for when school must start, according to data from the Education Commission of the States and individual state education agencies. But even in those states, the rules are fairly loose – merely requiring school to start before or after a certain date – and waivers for individual districts are not uncommon.

Contrary to popular belief, the school calendar isn’t a relic of the nation’s agrarian past. In fact, into the early 20th century, rural schools typically operated summer and winter sessions, with children working on farms in spring and fall to help with planting and harvesting. Urban schools, on the other hand, were open nearly year-round, though many children attended sporadically or for just part of the year.

Between roughly 1880 and 1920, urban and rural school calendars converged into more or less the pattern we know today, driven by factors such as pressure from education reformers, the high cost of keeping schools open year-round, the shift from one-room schoolhouses to age-graded education, and lower attendance in urban schools during the summer months (especially as family vacations grew in popularity).

Another possible explanation, for both the traditional calendar and the regional clustering of start dates, is “network effects,” in which a given standard becomes more useful as it’s adopted more widely. It’s easier, for instance, for a school district to recruit teachers from neighboring districts if those districts are on similar schedules.

School start dates could vary even more in the future with climate change. Some education experts predict hotter temperatures may force districts to adjust their start dates or times, especially in places like the Southwest, if schools can’t update air conditioning systems or make other accommodations.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published Aug. 14, 2019.