While more than 46 million Americans already have cast their votes this year, 80 million or so more will be voting on Election Day itself. If you’re one of them, there’s a good chance you’ll use one of two basic forms of voting technology to record your choices: optical-scan ballots, in which voters fill in bubbles, complete arrows or make other machine-readable marks on paper ballots; or direct-recording electronic (DRE) devices, such as touch screens, that record votes in computer memory.

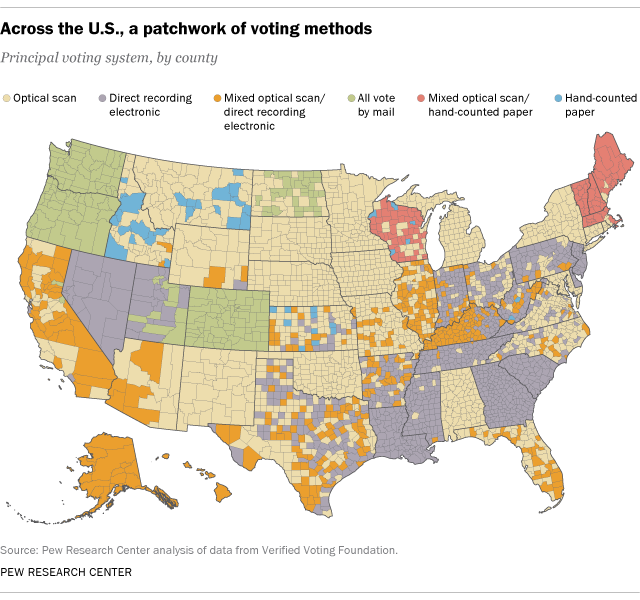

Nearly half of registered voters (47%) live in jurisdictions that use only optical-scan as their standard voting system, and about 28% live in DRE-only jurisdictions, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Verified Voting Foundation, a nongovernmental organization concerned with the impact of new voting technologies on election integrity. Another 19% of registered voters live in jurisdictions where both optical-scan and DRE systems are in use.

While those are the two dominant forms of in-person voting, they aren’t the only ones in use. Around 5% of registered voters live in places that conduct elections entirely by mail – the states of Colorado, Oregon and Washington, more than half of the counties in North Dakota, 10 counties in Utah and two in California. And in more than 1,800 small counties, cities and towns – mostly in New England, the Midwest and the intermountain West – more than a million voters still use paper ballots that are counted by hand.

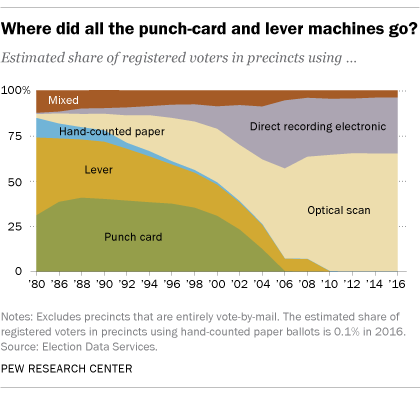

Beyond the rise of early, absentee and mail voting, the means by which Americans vote on Election Day have changed dramatically over the past generation. In 1980, when Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter, the two most common voting systems nationwide were punch-card devices and “lever machines” – self-contained voting booths in which voters flipped levers to indicate their preferences, with the totals automatically recorded on a built-in mechanical register when the voter opened the privacy curtain to exit the booth.

But the lever machines, which were first invented in the 1890s, were bulky and expensive to maintain and repair, and they were phased out over the next two decades. (New York State was the last to use them regularly, officially retiring them in 2010, though they’ve made a handful of guest appearances since.) Punch cards hung on throughout the 1990s but gradually lost ground to optical-scan and electronic systems – a decline that accelerated sharply after the 2000 Florida election recount debacle that brought the term “hanging chad” to brief prominence.

But as punch cards faded away (the last two jurisdictions to use them, Franklin and Shoshone counties in Idaho, abandoned them after the 2014 elections), some voters became concerned that fully electronic voting – in which votes are logged directly into a computer’s memory banks – would not generate any “paper trail” for future recounts. According to Verified Voting, of the 53,608 jurisdictions that use DRE equipment as their major voting method, almost three-quarters use systems that don’t create paper receipts or other hard-copy records of voters’ choices.

Verified Voting compiles data on voting equipment at the county (and, when relevant, the city, town or village) level. Warren Stewart, who maintains the organization’s database, said he uses the federal Election Assistance Commission’s biennial survey of election practices as a starting point, then cross-checks the EAC data with state and local election offices, news reports and industry information. The registered-voter numbers are from 2014, the most recent complete set available; while the voter rolls likely have grown since then, Stewart said, the overall percentages probably haven’t changed very much. (We should note that the map above depicts the voting method, or mix of methods, generally available to in-person voters on Election Day. Early and absentee votes frequently are cast and tallied differently, and federal law requires all polling places to make disabled-accessible voting systems available as well.)