The 2020 census could be the first in which most Americans are counted over the internet. In fact, if all goes as planned, the Census Bureau won’t even send paper questionnaires to most households.

The bureau’s goal is that 55% of the U.S. population will respond online using computers, mobile phones or other devices. It will mark the first time (apart from a small share of households in 2000) that any Americans will file their own census responses online. This shift toward online response is one of a number of technological innovations planned for the 2020 census, according to the agency’s recently released operational plan. The plan reflects the results of testing so far, but it could be changed based on future research, congressional reaction or other developments.

Starting next month, the agency will conduct test censuses of 225,000 households each in Los Angeles County and Harris County, Texas, which includes Houston. Further tests are planned into 2019. The bureau also is testing use of other government or third-party records to supplement the census-taking, as well as experimenting with new question wording on race, ethnicity and relationships.

[callout align=”alignright”]

Try our email course on the U.S. census

Learn about why and how the U.S. census is conducted through five short lessons delivered to your inbox every other day. Sign up now!

“We are innovating the way that census and survey taking will occur …. It’s transformational,” Lisa Blumerman, the bureau’s associate director for decennial census programs, told a briefing last month.

However, the bureau has dropped or may restrict use of some technology ideas because of the potential for fraud. In addition, the Government Accountability Office has raised concerns that the bureau is running out of time to make key technology decisions, though bureau officials say they are three years ahead of where they were in their planning for the 2010 census.

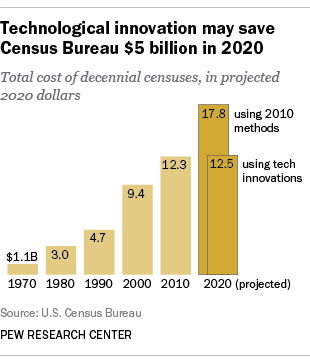

The Census Bureau innovations are driven by the same forces afflicting all organizations that do survey research. People are increasingly reluctant to answer surveys, and the cost of collecting their data is rising. From 1970 to 2010, the bureau’s cost to count each household quintupled, to $98 per household in 2010 dollars, according to the GAO. The Census Bureau estimates that its innovations would save $5.2 billion compared with repeating the 2010 census design, so the 2020 census would cost a total of $12.5 billion, close to 2010’s $12.3 billion price tag (both in projected 2020 dollars).

The bureau plans to incorporate technology from start to finish of the 2020 census. As the census gears up, technology will help the bureau compile its list of mailing addresses, which is the backbone of every census. In the past, census-takers have walked all 11 million blocks in the country to compile the mailing list. For 2020, the agency will walk 25% of blocks and do the rest from the office, using digital imagery and other sources.

In contacting most households, the bureau will not include paper forms. Instead, its letter will include a unique security code and will urge people to use it to respond online. (The bureau is still studying whether to contact people by text message through mobile phones.) People without computers at home could go to community centers that partner with the bureau, where they could access the internet and get assistance.

The only households receiving paper forms under the bureau’s plan would be those in neighborhoods with low internet usage and large older-adult populations, as well as those that do not respond online.

To maximize online participation, the Census Bureau is promoting the idea that answering the census is quick and easy. The 2010 census was advertised as “10 questions, 10 minutes.” In 2020, bureau officials will encourage Americans to respond anytime and anywhere – for example, on a mobile device while watching TV or waiting for a bus. Respondents wouldn’t even need their unique security codes at hand, just their addresses and personal data. The bureau would then match most addresses to valid security codes while the respondent is online and match the rest later, though it has left the door open to restrict use of this option or require follow-up contact with a census taker if concerns of fraud arise.

The larger the share of Americans who respond on their own, the more money the Census Bureau will save, because the most expensive part of the census is sending census-takers to knock on doors to get information from millions of people who don’t provide it. The bureau plans to use technology to make their route assignments more efficient, reduce the number of times they have to knock on any one door and let supervisors track their progress.

The census-takers will carry mobile devices to collect information from households. In the 2010 census, the bureau encountered numerous problems with handheld computers it had ordered from a contractor and census-takers reverted to pencils and paper to collect information from people who did not respond. For 2020, the bureau had explored the idea of letting those 300,000 enumerators use their own mobile phones or tablets, but scrapped that because of concerns it could lead to delays, financial fraud and other problems. Instead, the bureau plans to purchase equipment from a contractor and equip it with an app for enumerators to use.